To mark International Women’s Day, Hagerty is giving a platform to women driving change. Catch the other stories in this series and read about the 13-year old karting sensation, and women driving change in the automotive scene.

Who are the women who made automotive history? There are too many to choose from, but choose we must. So in celebration of the 110th anniversary of International Women’s Day, we present 11 of the most innovative, influential, adventurous and daring women who have helped drive change in the automotive space. The trailblazing decisions these women made in the past continue to make a difference today.

Odette Siko

The first woman to race at Le Mans

When the French flag was lowered to signal the start of the 24 Heures du Mans on the 21st June 1930, Odette Siko made motorsport history as the first woman to race the endurance classic. Competing alongside Marguerite Mareuse in a Bugatti T40, they made it home in seventh position – a result that’s yet to be beaten by an all-female team. They were the first, and remain the best.

A year later Siko and Mareuse, both French, were disqualified for a refuelling infringement. It did not put her off; Siko would contest Le Mans twice more. In 1932 she claimed fourth spot overall and a class win aboard an Alfa Romeo 6C 1750 with Louis Charaval – another record finish for a woman that still stands today. In the 1933 event, Siko skidded off the circuit on her 120th lap. Her car hit a tree and caught fire, but despite her best attempts to extinguish the flames she was forced to retire from the race.

Siko continued to compete throughout the 1930s, earning plaudits for her performances in speed trials and rallying, but her career petered out with the beginning of the Second World War. Away from racing, she was an accomplished tennis player, and it’s a little known fact that she achieved her fame under a pseudonym; she was born Odette Séguin in 1899.

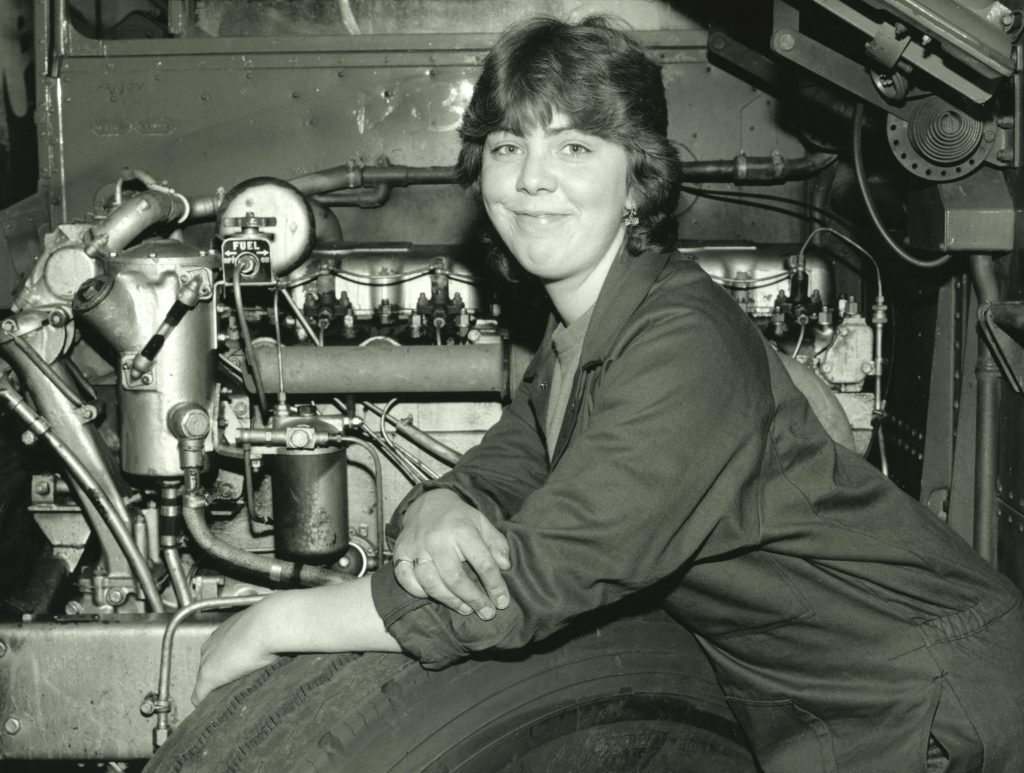

Helen Clifford

London Transport’s first female bus mechanic

Next time you hail a London bus, spare a thought for Helen Clifford – the first woman to be officially responsible for keeping the capital’s iconic mode of transport on the move.

In August 1984, at the age of 18, Clifford qualified as London Transport’s first female bus mechanic after completing a course at West Ham garage. Up until then, women had only been given the temporary opportunity to take on what were considered typically male roles in stations, garages, depots and engineering works during the First and Second World Wars. It’s likely that Clifford would have worked on the RM type, best known as the Routemaster, as well as cheaper off-the-peg buses and driver-only operation that were used on some routes to reduce costs.

Clifford was also a qualified bus driver, a position which was opened up to women in 1974. That didn’t stop London Transport launching a recruitment campaign in 1980 that ran adverts which played on the then-prevalent, and untrue, stereotype that women were poor drivers.

Beatrice Shilling

Meccano fan, engineering genius, motorbike racer and World War Two hero

Beatrice “Tilly” Shilling’s story is one of two wheels and wings. Born in 1909, she spent her childhood playing with Meccano and her pocket money on tools. Championed by The Women’s Engineering Society, Shilling realised ambitions that were way ahead of her time. In 1932, when she graduated from the University of Manchester with an honours degree in engineering, she was listed as ‘Mr’ on her student record card, as female titles were not yet a recognised option.

In 1934, Shilling became the second woman to be awarded a Brooklands Gold Star when she recorded two laps at over 101mph. She’d fitted her Norton motorcycle with a revolutionary supercharger and later became the circuit’s fastest female racer ever with a lap speed of 106 mph. There are even whispers that she refused to marry her husband, George Naylor, until he had achieved his own Gold Star. To help inspire young minds, Brooklands museum has celebrated her with a colouring-in activity, available for download here.

When the Second World War broke out, Shilling was working for the Royal Aircraft Establishment. Doing her bit to help win the Battle of Britain, she invented a restrictor valve that prevented RAF Spitfires and Hurricanes from stalling due to fuel starvation and falling from the sky during steep dives. She was later awarded an OBE for her efforts. Today would have been her 112th birthday.

Pat Moss

World leading rally driver

“What she managed to do was amazing, actually,” said Sir Stirling Moss, when asked about his younger sister Pat, who built her formidable reputation on outright wins and podium finishes at international rallies throughout the 1950s and 60s. It was high praise from a man who wasn’t noted for his championing of women in motorsport.

Moss’s maiden event took place in 1953, when she competed in her Morris Minor convertible at the age of 18. She went on to be crowned five-times European Ladies Rally Championship winner and the Coupe des Dames on the Monte Carlo Rally eight times. Moss also won the gruelling 1960 Liege-Rome-Liege Rally in a fearsome Austin Healey 100/6, and went on to finish second at the Coupe des Alpes.

In 1962 Moss took victory at the Tulip Rally with a pregnant Ann Wisdom on board as co-driver. The formidable pair gave the newly-introduced Mini Cooper its first success on an international stage; Moss described the vehicle as “twitchy and unruly on the limit.” Her speed wasn’t just limited to competition either – shortly before her death in 2008, Moss collected a speeding ticket while towing a horse box!

Minnie Palmer

First woman in England to own and drive her own car

In 1897, Minnie Palmer became her own chauffeur. Distinguishing herself as the first woman in England to own and drive her own car, the American-born actress took delivery of a French-made Rougemont automobile.

It was 31 years before women achieved the same voting rights as men, but Palmer’s move proved that the sexes could be equals behind the wheel – a significant milestone on the road to the social and political emancipation of women.

Soon after, a small army of women established driving schools and repair shops which provided a ready resource of skilled workers that was drawn upon during World War One. The car was becoming a tool through which women could redefine their identity in the world of work.

Dorothée Pullinger

Engineer and entrepreneur who designed a car for women, that was built by women

Dorothée Pullinger made room for women in a man’s domain, and designed a car fit for them too. Born in 1894, her time to make a difference came during the First World War when she was in charge of an estimated 7000 munitions workers producing bombs for the front line. She’d been refused entry to the Institution of Automobile Engineers on the grounds that “the word person means a man and not a woman” – a decision that was later reversed.

By the early 1920s Pullinger was manager of Galloway Motors, a car factory run by a female workforce that adopted the colours of the suffragettes. An on-site engineering college offered women apprenticeships that lasted three years, rather than the usual five for men, because it was believed women were faster learners.

Pullinger also designed and developed the Galloway – the world’s first car specifically for, and built by women. The proportions of Edwardian cars were often too large to accommodate a smaller female frame, so the gear levers in the Galloway were placed inside rather than outside so that they were easier to reach. The seat was also raised, the dashboard lowered and the steering wheel was smaller.

One of the first automobiles to introduce a rear view mirror as standard, Pullinger’s pride in the Galloway was justified. She piloted it in the Scottish Six Day Trials, an event for motorists to demonstrate their vehicles to crowds, and won in 1924. Only 4000 were ever made, and one of them is on display at Glasgow’s Riverside Museum. Pullinger was a founding member of the Women’s Engineering Society.

Dorothy Elizabeth Levitt

First British female racing driver who set records, carried a revolver in her glove box and taught royals how to drive

Hackney-born Dorothy Elizabeth Levitt was described as “the fastest girl on earth” when she set a new world speed record for women, of 91mph. She did it in a six-cylinder Napier during a speed trial at Blackpool in 1906. Three years earlier she had been garlanded with the title of Britain’s first female motor racing driver, and also set the world’s first water speed record when she achieved 19.3mph in a 40-foot steel-hulled, Napier-engine speedboat fitted with a 3 blade propeller.

In 1905, the Londoner set another record, for the “longest drive achieved by a lady driver” for a return journey to Liverpool from the capital. Her accomplishments made her a media sensation, and so a little controversy was never too far away. When stopped for speeding at a “terrific pace” her unremorseful response, so say the rumours, was that she would “like to drive over every policeman and wished she had run over the sergeant and killed him.”

In her 1909 book, The Woman and the Car: a Chatty Little Handbook for All Women who Motor or Want to Motor she advised women to carry gloves, chocolate and a revolver in the drawer under the driver’s seat. The gossip and scandal however, didn’t overshadow Levitt’s talent. Although unconfirmed, it’s thought she was called upon to teach Queen Alexandra, wife of King Edward VII, and the Royal Princesses how to drive. Her black Pomeranian dog, Dodo, remained her most faithful driving companion, even when competing.

Margaret Wilcox

Invented the in-car heater

For early adopters of the motor car, driving was open-air enjoyment in its purest, and sometimes frostiest, form. On the 28th November 1893 Margaret Wilcox patented a solution: the world’s first in-car heating system.

It took decades for car makers to warm to her idea, which was considered a luxurious optional extra even when fully enclosed bodywork and glass windows became more widespread, but finally, in 1929, the Ford Model A became the first vehicle to offer in-car heating at the point of manufacture.

For Margaret, the design also represented a turning point in her career as an inventor; it was the first to be patented in her own name rather than her husband’s. It wasn’t until 1809 that women in the United States were given the right to do this.

Mary Anderson

Inventor of the windscreen wiper

You can see clearly now because inventor Mary Anderson spotted a problem that needed solving when she took a streetcar ride on a snowy day in New York City. To clear the ice from his windscreen her driver had to open the window, chilling his passengers in the process.

Anderson’s solution was a rubber blade attached to a spring-loaded arm that would move back and forth across the glass to wipe away the weather. Secured on the outside and operated from the inside, a counterweight was used to ensure contact between the wiper (which swung from a downward position) and the window.

Mary patented the design in 1903 but it wasn’t an instant hit with car companies, who thought it would distract drivers. She never profited from her invention, even when wipers became a standard on cars. She did, however, get a name check in an episode of The Simpsons in 2006.

Bertha Benz

Pioneer of the long-distance car journey and inventor of brake linings

Bertha Benz is the original road-tripper. Early one August morning in 1888 she set off in her husband’s car, without permission, spare fuel or a map, to make the 106km (66-mile) journey from Mannheim to Pforzheim in Germany. Her husband was Karl Benz, and the car was the world’s first.

Powered by an internal combustion engine with an output of barely one horsepower, hills could be problematic for Karl’s three-wheeled Benz Patent-Motorwagen. It could also topple easily, but these design flaws did nothing to deter Bertha, who believed it was ready for the open road, and that the world was ready to see a woman setting its new course. Her pioneering drive wasn’t without incident, but Benz’s stoicism and ability to adapt and improvise makes her even more impressive. When the Patent-Motorwagen’s engine overheated, she used water from ditches and streams to cool it, and when a fuel line became blocked, she cleaned it with her hat pin. She even used her garter as insulation material and paid a cobbler to cover the brake shoes in leather – and in doing so invented the world’s first brake lining.

It was inevitable that she’d run out of fuel, but she found a pharmacy in Wiesloch, which is now considered the first petrol station in history, and purchased ligroin (a petroleum based solvent). Benz arrived at her destination 12 hours after departing, and sent Karl a telegram to let him know that she’d successfully completed the first long-distance journey in his motor car. In his autobiography Karl Benz wrote: “In those days when our little boat of life threatened to capsize, only one person stood steadfastly by me; my wife. She bravely set new sails of hope”. Bertha died in 1944, aged 95.

Vera Hedges Butler

First British woman to pass a driving test

In 1900 Vera Hedges Butler was the first British woman to pass a driving test, but she had to go to Paris to do it. Assessed on her ability to pull away, steer and stop, she also had to demonstrate knowledge of what to do in the event of a breakdown.

Thirty-five years later, a Mr Beere of Kensington became the first learner driver to earn a pass certificate in Britain after testing became compulsory on 1st June 1935. He paid a grand total of 7s 6d (37.5p) to take it and would have met his examiner in a post office, town hall or railway station car park because designated test centres were yet to be established.

At times of national crisis, driving tests have been suspended by the government. During World War Two examiners were redeployed to traffic duties and supervision of fuel rationing, and most recently because of Covid-19 restrictions. Tests in 2020 were down 35,000 in comparison to 2019.

I think the car that Pat Moss won the Liege in was classed as a Healey 3000, it had a 4 speed gear box instead of the standard 3 speed, with overdrive on all but 1st.

How wonderful that women are some innovators in the automobile world, such as windscreen wiper, and heaters, you’d think that big car manufacturers of that time would have thought of that, there are household names such as Pat Moss that most people have heard of, but it’s nice that other ladies have been recognised for the work in the car world

Beatrice Shilling: The restrictor valve invented by this lady and fitted to the Merlin engines became known throughout the RAF as Miss Shilling’s Orifice. (!)

Surely Kay Petre should get a mention !!!

Is Gillian Lowinger the first woman to ride a Vincent Black Shadow?

I can’t believe that you did not include Michele Mouton, the only lady to win a World Championship!!

No mention of Ethel Locke King, who, with her husband, Hugh Fortescue Locke King created a motor racing circuit in 1907 on their Brooklands Estate in Surrey?

,

Significant that modern women do not appear on you list, apart from the bus mechanic

Doubtful.

You might have included the Queen, who as Princess Elizabeth, served with the ATS – Auxiliary Territorial Service – and trained as a driver and mechanic. She was given the rank of honorary junior commander (female equivalent of captain at the time). Photograph TR 2832 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums, shows her in ATS uniform, April 1945, standing in front of an ambulance. (Wikimeadia Commons).

Rosemary Smith also ignored – again ! This subject requires a much bigger outlet.

The ’56-58 Austin Healey 100/6, which was a ‘big’ Healey with a 2.6 litre 6 cylinder engine, had a 4-speed gearbox with optional overdrive and drum brakes. It was replaced by the 3000 Mk1 in 1959 which was essentially the same car with a 3.0 litre engine and front wheel disc brakes. In the ’70’s I owned a ’58 100/6 2-seater with Dunlop 4-wheel disc brakes as used on the earlier 100’S’ competition version of the 100/4; I have since learned that some 50 such cars were so equipped and sold for the purpose of homologating the all disc brake set-up used on some late 100/6 and all subsequent 3000 Abingdon ‘works’ competition cars. I believe Robin is correct that Pat Moss used a 3000, unless it was an updated 100/6, to win the Liege rally but it was the ’53-54 100/4 BN1 Healey that had a 3-speed plus O/D gearbox, although, as it came from an Austin A90 saloon it was really a 4-speed box with 1st gear blanked off because it was too low for the Healey. This meant all three gears had synchromesh and , with the addition of overdrive on second and top, I imagine this might be quite a pleasing set-up, although I have never driven one; the ’55 BN2 a 4-speed box as did the 100’S’. If you have seen the rather strange gear levers on the 100/4 (particularly), 100/6 and 3000 Mk1 this is because they were designed for column change!

Some excellent inclusions particularly that amazing engineer Beatrice Shilling, plus Pat Moss, but Michele Mouton just has to be included. I also agree with the suggestions of Kaye Petre as well as Rosemary Smith (winner of the Tulip rally & a highly skilled driver in rallies and on the track – as I know at first hand). Rosie also provides an interesting link to Odette Siko / Seguin as she was not permitted by the organisers (ACO) to race at Le Mans as a member of the Rootes team of Sunbeam Alpines in the early 1960s, simply because she is a woman. But that in itself is quite a story which is best to hear told by the great lady herself.

So good to see my god mother being recognised in the list. Bea Shilling should be a house hold name

I think it goes without saying that this story could be extended but how very fascinating it is.

”Good driving has nothing to do with sex. It’s all above the collar”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice_Huyler_Ramsey

Judi Derisley. I am a retired aircraft engineer working on Merlin engine in the 60s I can assure you that her name is well known in my household.

Desire Wilson, Only woman to win a Formula one race 12th April 1980 at Brands Hatch British F1 championship.

Don’t give me it wasn’t a real F1 race, it was fun to F1 regs