The Aston Martin DB5 with the guns and ejector seat. A submersible Lotus Esprit equipped with missiles. How about the Toyota 2000 GT, a coupe so compact the film producers had to turn it into a convertible so that the late, great Sean Connery could actually fit into it?

When it comes to choosing the best cars featured in the James Bond film series, expect the usual suspects to come out on top. After all, we’re talking about the most famous cars in the world here, driven by the single best-known fictional character in all of cinema. But across 25 films – we’re still waiting to see the Covid-delayed No Time To Die – hundreds of other cars have made their bid for celluloid stardom.

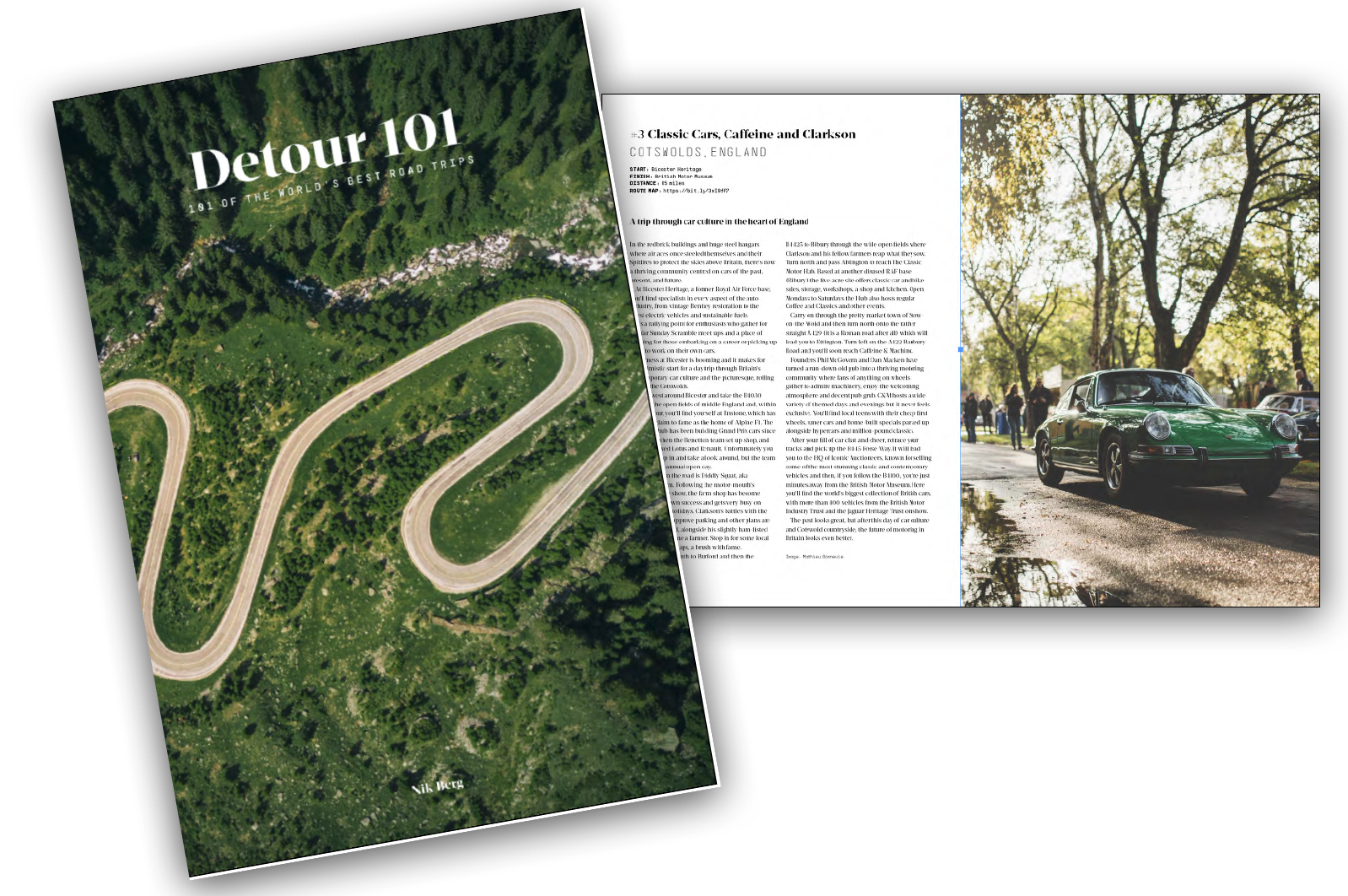

In researching and writing Bond Cars: The Definitive History I have come to learn so much more about the cars that played the four-wheeled supporting cast in the Bond blockbusters. Access was granted to the original call sheets, technical drawings and story-boards and even previously unpublished photography. And there have been insights from the producers and keepers of the Bond flame, including Michael G. Wilson and Barbara Broccoli as well as Daniel Craig. Oh, and there’s one other name you may not be familiar with; Chris Corbould, the special effects and action vehicles supervisor and veteran of 15 Bond films.

So, reaching for the clapboard, here are seven lesser-known Bond cars, plus a few things you probably didn’t know about them…

Sunbeam Alpine | Dr No, 1962

What’s the first car driven by James Bond on screen? That would be the Chevrolet Bel Air convertible that 007 finds himself returning to Government House in Jamaica, his driver newly deceased in the back seat. But the first bona fide Bond car is the Sunbeam Alpine, a series II version of the Rootes Group roadster that was launched in 1959. Its design was supervised by legendary French industrial designer Raymond Loewy, whose vast CV encompasses the interiors for NASA’s Skylab and Apollo missions, the Lucky Strike logo, and the outlandish Studebaker Avanti. Bond’s car was powered by a twin-carb fed 1.6-litre that produced 80bhp, just about enough to keep him ahead of the baddies in the first of many dramatic car chases he’d become embroiled in.

On the day this particular sequence was shot, the crew arrived to discover a huge excavator blocking the road. Director Terence Young simply decided to incorporate it, Bond stunt legend Bob Simmons doubling for the late Sean Connery as the Sunbeam passed at speed under the digger. ‘Terence told me afterwards that he saw the car start to bounce only split seconds before I went under,’ Simmons recalled. ‘I had a difficult time bringing the car to a controlled stop.’

Lincoln Continental | Goldfinger, 1964, Thunderball, 1965

Overshadowed by the Aston Martin DB5, Goldfinger’s Rolls-Royce Phantom III Sedanca de Ville and even Tilly Masterson’s Ford Mustang – only just launched in time for filming – the Lincoln Continental nevertheless figures prominently in 1964’s Goldfinger. This was the first Bond film in which the primary villain had an equally murderous majordomo, Oddjob (you may recall his lethal bowler hat). He also drove a magnificent Lincoln Continental, using it to dispose of the one Mafioso who refuses to play ball with Goldfinger’s grand plan.

Crushing the car didn’t sit well with the film’s production designer, the great Ken Adam. ‘I’ll never forget that we were completely speechless to see this beautiful new Lincoln, minus its engine, being squashed and ending up as a cube,’ he recalled. So much so that both a Continental convertible and limo make appearances in the next Bond film, Thunderball. More than just a car, the big Lincoln was an important piece of mid-century modernism in its own right, its era-defining design overseen by Ford’s chief stylist Elwood Engel. ‘I want a clean car – no garbage!’ he told his team

Moon buggy | Diamonds Are Forever, 1971

Not a Bond car, but certainly a memorable Bond vehicle. Despite an increasingly frosty relationship with producers Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, Sean Connery brokered an unprecedented deal to return as 007 (part of which included setting up the Scottish International Educational Trust, to which he donated his fee for the film). The film-makers had a deal with Ford for Diamonds Are Forever, and the film is practically an early Seventies Blue Oval period piece. Then comes the Moon Buggy sequence, an incongruous, quasi-comic blast of futurism.

Designed by Ken Adam and made by Californian custom car scenester Dean Jeffries – who’d pinstriped James Dean’s Porsche 550 Spyder and also created the Monkeemobile – Bond’s escape across the Nevada desert was an action set-piece that demanded more than the buggy was originally designed to handle. Fitting it with balloon tyres helped, but you can see one of its wheels flying off in the film.

AMC Hornet | The Man With The Golden Gun, 1974

A forgotten little shopping car from a now forgotten and unlamented American car maker, the Hornet stakes a claim to immortality as the star of possibly the single greatest stunt in the entire Bond canon. When Guy Hamilton, director of 1974’s The Man With The Golden Gun, saw a company called JM Productions execute an astro-spiral jump in one of its big mid-west carnival car shows, he figured it would work in the film.

The stunt, in which the Hornet does a 360 degree jump across the Khlong Rangsit canal near Bangkok, was done for real, supported by some early computer modelling. The driver, Lauren ‘Bumps’ Willert, sat in the centre of the car with two dummies either side of him. When Hamilton wondered if the first take had been almost too good and was considering another run, Willert confessed that it was the first time he’d ever done it, and was in no great rush to give it another go…

Citroen 2CV | For Your Eyes Only, 1981

The unwitting star of one of the best Bond car chases. After sending 007 into space, the producers and first-time director John Glen figured it was time to bring Bond back to Earth. When his Lotus Esprit Turbo is blown up, he’s forced to use a 2CV to flee a gang of assailants. Shot in Corfu, Glen was keen to keep things real. ‘We wanted everyone to get involved with the chase sequence, otherwise the cars can look like toys. You need to be able to relate to them.’

Rather than its usual puny 602cc two-cylinder, the Citroen was fitted with the 1.1-litre engine used by the larger GS model. French stunt driving royalty Remy Julienne masterminded the sequence, in which the longed-for reality was tested somewhat by the 2CV’s apparent indestructibility as it somersaulted through an olive grove.

ZAZ 965 A | Goldeneye, 1995

A joke car? Perhaps. But it’s also used to scope out elements of the character who owns it in the film, CIA officer Jack Wade (Joe Don Baker). The Zaporozhets ZAZ 965 A was conceived by the Kremlin as its Sixties ‘peoples’ car’, although it was still too expensive for the vast majority of the population. Air-cooled and minimally designed and engineered, this was a car its owner could easily repair at the road side. As Wade demonstrates to a disbelieving Bond (Pierce Brosnan, in his first outing as 007) in a square in St Petersburg.

Aston Martin DBS | Casino Royale, 2006, Quantum of Solace, 2008

Not the Aston usually cited during discourse over Bond cars, but something of an overlooked gem in the company’s recent history. The DBS was effectively premiered in 2006’s Casino Royale, the first of Daniel Craig’s five outings as Bond. Powered by a 5.9-litre, 510bhp V12, Aston’s design director Marek Reichman even incorporated aspects of Craig’s more physical Bond persona into the car’s design as he evolved it.

It meets a seriously sticky end in the film, as 007 swerves to avoid Vesper Lynd (Eva Green), and proceeds to barrel roll enough times for the stunt to qualify for an entry in the Guinness Book of Records – it rotated fully seven times. The stunt crew tried using a ramp to get the DBS airborne, but it proved too stable. So they resorted to the tried and tested air cannon, which used pressurised nitrogen to trigger a ram in the car’s floor. That did the trick.

Bond Cars: The Definitive History by Jason Barlow is available now from all good booksellers, published by Ebury Press, and costs £20