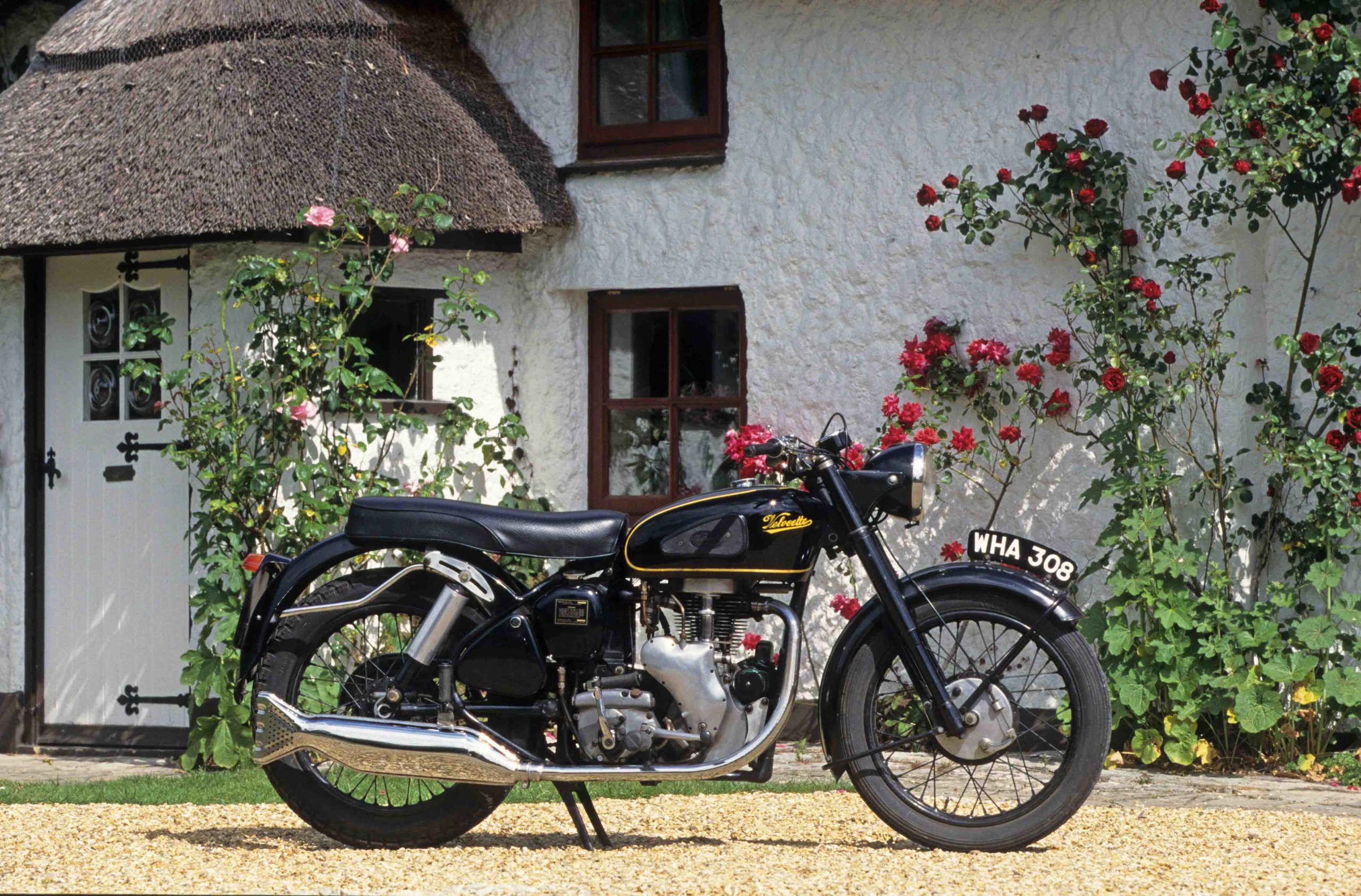

In my garage I have a shoe. Just the one, a very sturdy right-foot walking boot with a nice steel shank in its sole. It’s old and battered and its left-foot sibling is long gone but this one shoe lives in my garage, ready for when it is called into action. What requires just a single shoe? Starting a British classic motorcycle, in my case a 1960 Velocette Venom.

It may sound odd keeping a shoe just to kickstart a bike with but in the world of classic British bikes, this kind of procedure is quite normal. I know owners who have set rituals and even go as far as to approach their bike from a certain angle (generally behind…) so it doesn’t get wind that they may be attempting to coax it into life and protest.

There again, I also know owners who only buy a certain colour of classic so their significant other doesn’t realise just how many old bangers they have amassed. It’s a strange old world full of colourful characters. But back to the Venom.

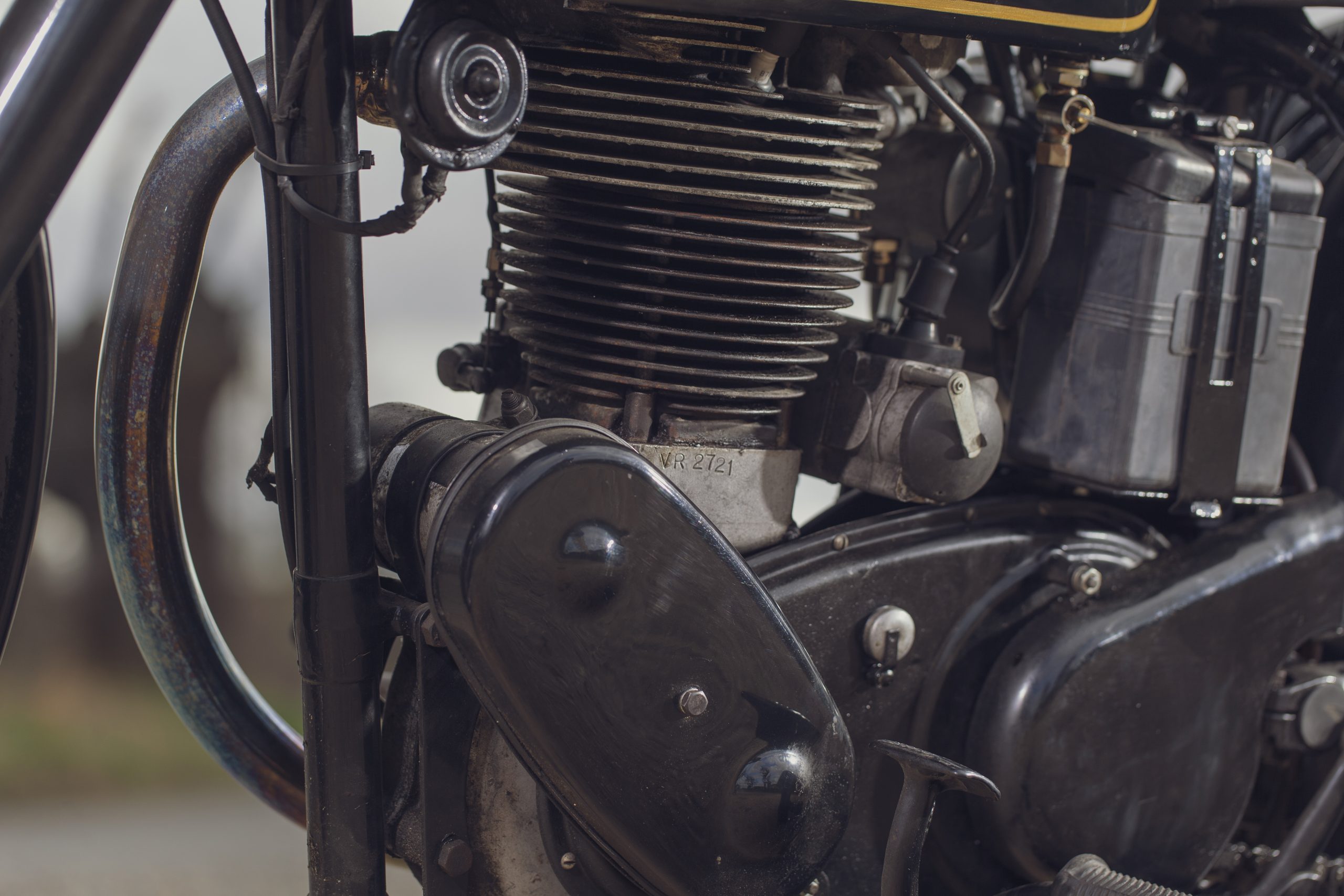

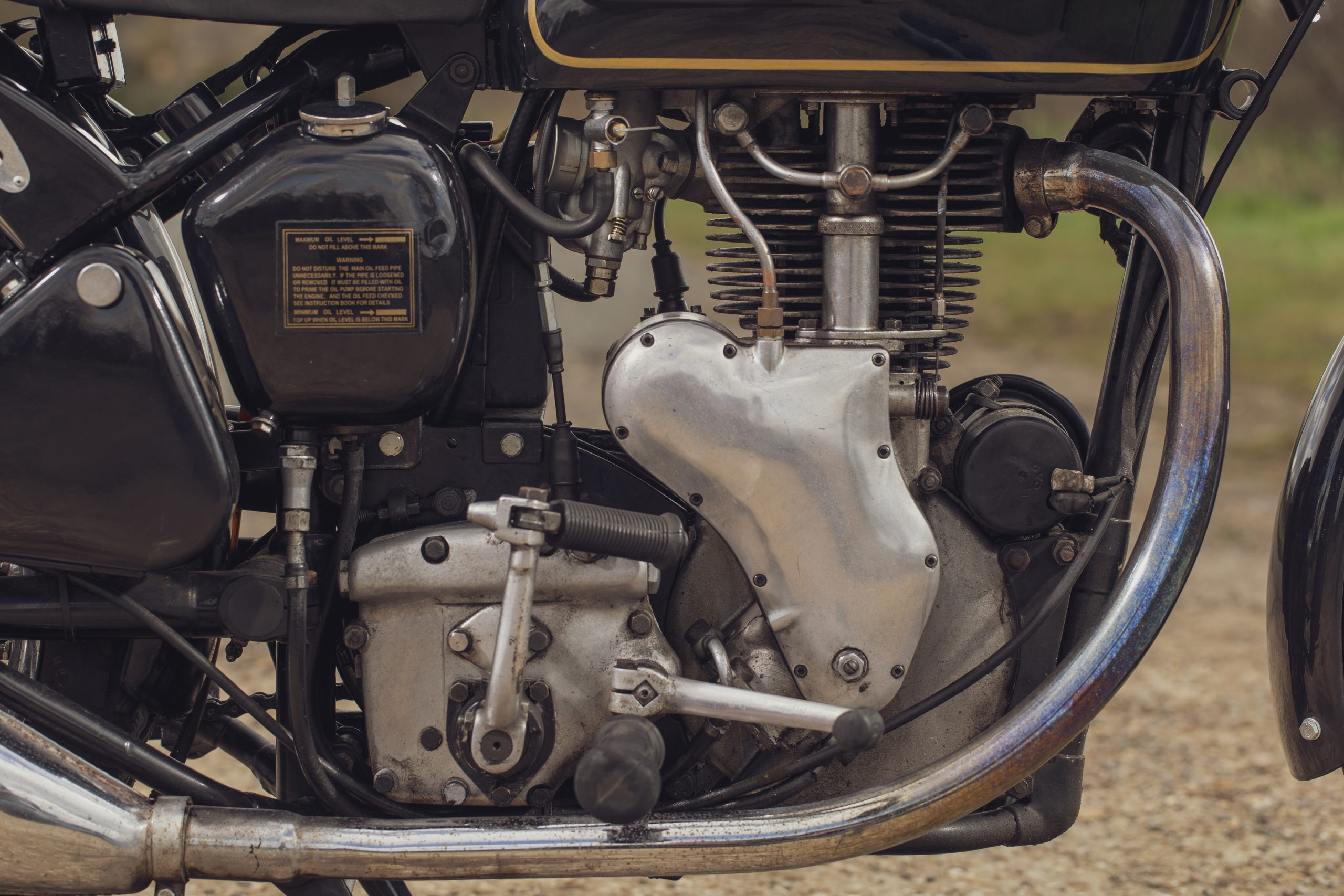

The issue with a Venom is two-fold. As with so many British bikes of the period it is a single cylinder with a capacity of 499cc, which means it has a fairly high compression ratio you need to overcome with the kickstart to get it to fire up. And typically for British bikes of the era, Velocette’s engineers didn’t really think it through. While there is a lever that lifts a valve to release the compression to help you get the motor ready for its kick (reach top dead centre, pull in the decompressor, one slow kick down, back to the top and KICK!) that is only half the battle as the kickstart lever itself is very short. A short kickstart equals no leverage and with a Venom you get one stab at it starting as the kick only turns the engine a single rotation. If you get it right the bike fires gloriously into life. Get it wrong and the kickstart bites back with terrifying aggression that will break you ankle if you aren’t careful – hence the sturdy walking boot.

These are all things you learn the hard way when owning a British classic. And owning one is most certainly a continual learning process. Often an incredibly frustrating one but also unbelievably rewarding when all goes well. So how did a 44-year-old with, I have to admit, little interest in British classics end up with one?

Like a lot of riders my age, I grew up in a family where bikes were always around. My dad, who basically lives in his workshop and washes in oil, is into vintage and classic vehicles and while I was growing up he commuted on the Vello to work. To me it was ‘dad’s bike’, not a classic. When I was old enough I got a bike licence, crashed through most of the hedges in the Cotswolds on Japanese bikes, and then when I was 18 dad gave me the Vello. But I was young, wanted to go fast and after owning a Japanese bike, which had an electric start and would do 100mph, I wasn’t interested in the wobbly-handling and vibey Vello so I handed it back. Dad continued to ride it but when he retired he sold the Vello as the whole starting procedure was getting too much for him. Fast forward a decade or so and dad happened to mention the chap he sold it to had died and the Vello was back on the market. I got in touch and bought back ‘dad’s’ Vello.

Why? A combination of sentiment and age. By then in my mid-thirties and not such a speed-freak I appreciated the Vello for what it was and dad was going through a bit of ill health, so it meant a lot in memories. Machines can do that, just ask anyone who is into classics, the memories they conjure up are as important as the actual riding experience.

So, with the Vello now in my garage I made a decision. In retrospect possibly not a very good one but a decision – I would restore the Velocette, mainly for dad to see as he was fighting prostate cancer at the time. I’m fairly handy with spanners and the great thing about British bikes is that they are pretty simple. Once you work out what on earth size spanner fits (you need to learn fractions and inches and buy a whole new toolkit…) they come apart really easily. There again, most things come apart easily, it’s the putting back together again that is the tricky part.

Various bits went to powder coaters and I located new parts where required through the specialists. Owning a British classic isn’t a worry in terms of spares, there are specialists all over the UK and most parts are available. And putting it back together isn’t too tricky either – there is actually a Haynes manual on the Vello! I thoroughly enjoyed the whole process, even going as far as to build my own wiring loom. But then, with the bike back in one piece, the reality of owning a British bike hit home.

Classics have their quirks and although I didn’t take the engine or gearbox apart, I did have to remove the Vello’s clutch. What no one told me is that this particular part was designed by Satan and is basically impossible for anyone aside from a Velocette clutch whisperer to set up correctly. After months of fighting it, and a wasted trip to one so-called expert, I lost the will and the Vello was retired to a dark corner of my garage looking beautiful, running perfectly but unable to actually drive anywhere due to the clutch slipping – and it pains me to admit that that’s where it stayed for about three years.

It was heart-breaking as I felt I’d failed and dad’s Vello was now off the road. This kind of scenario is common for classic bikes as they can be challenging – but help is at hand. Reading an article on Vellos in a magazine I saw a number for a chap in Swindon who was an expert. I called him up, explained the issue and a few weeks later stuck the bike in a van and delivered it to him. He took one look, pointed out a few things I had incorrectly fitted and then two weeks later called me up. He had rebuilt the clutch (and forks…) and all was well – dad’s Vello was back on the road. And that’s how it still is.

Come a sunny day, I love getting the Vello out and going for a short ride. Speed isn’t an issue – I now appreciate the sound, feel and whole riding experience you get on a classic. The vibrations from the single-cylinder engine, smell of burning oil (which remains on your clothes for days afterwards), backfires on over-run, it’s a visceral adventure that you simply don’t get on a modern bike. I happen to gain this experience on a Velocette Venom but there is a wealth of classic bikes out there such as a BSA Gold Star, Norton International or Commando, Royal Enfield Interceptor, Triumph Tigers, you name it. The actual model doesn’t matter, it’s the memories that count, although as a rule of thumb if you just want a classic, buying a popular one is often better as that means parts and experts are more plentiful.

Nowadays a lot of classic bike owners are like me – they have either come into ownership through inheritance or after a bereavement, had a bike passed down as their parent has become too old to ride or they have simply bought one for sentimental reasons. And this means they lack the crucial knowledge that turns a British classic from a bike that sits there sadly gathering dust and dripping oil to one that will start and can be enjoyed, while dripping oil, naturally.

I was, and thankfully still am, very lucky with my Vello as dad won his battle with prostate cancer and therefore is on hand to help with any technical enquiries I may have but the key to owning a British classic is the support network. This can be owners groups, a local expert or a Facebook page. British bikes are incredibly simple and once you get one set up correctly, they generally remain that way and all you need to do is change the oil (or more accurately top it up as they self-change by dropping it on your garage floor!) and put air in the tyres.

Unlike our parents we won’t be commuting on a classic, they are for sunny days and short, nostalgic, rides. And swearing at. There is nothing more embarrassing than a whole crowd of people watching (and offering ‘helpful’ advice) as you attempt to kickstart a reluctant classic into life outside a pub…

Read more

Friends reunited: Why I need a Norton Commando back in my life

Ride on time: 13 collectable motorcycles to buy now

Bike inspections at 4am and daredevil bikers who didn’t have a licence: a rider’s memories of the White Helmets display team

Looks brilliant, great write up, I’m thinking about buying a venom. I ride a bmw r1150gs and had other Japanese bikes and bmws but I just love the look of the velo ……. its got character and history. Its a reminder of when we were the best in the world.