You’ve probably heard the acronym bandied about and possibly been a little unsure what on earth someone is talking about when they mention JDM cars. Well, it stands for Japanese Domestic Market, and it’s a scene that has sprung up in places like Britain, Europe and America, celebrating special cars imported from Japan.

At this point you might be wondering why someone like me, who has spent years working as a journalist for the likes of Autocar and What Car?, before going freelance, has a thing for imported cars which may or may not have a patchy history. Certainly, my former colleagues would, from time to time, ridicule me for my overt affection for these renegades from the Far East. But hey, what do people like Chris Harris know?

The roots of my love for JDM cars are two-fold. First, I have the World Rally Championship to thank. Just thinking about the WRC takes me back in time to when unimaginably cool drivers like Carlos Sainz campaigned a Toyota Celica GT-Four, Tommi Mäkinen went flat out in the Mitsubishi Lancer Evo and our own Colin McRae adopted a flat-out or bust approach in the Subaru Legacy and Impreza.

This interest in all things WRC was sparked by my Dad’s club rallying, and I suppose you could say he was the chief reason for why I grew up obsessing about cars. But inevitably the Japanese manufacturers’ domination in WRC made an impact.

Then, as the 20th century and many of WRC’s brightest moments started to dim, things took what, to many, was deemed an unwholesome turn for the millennial car fan. Enter the first Fast and Furious film.

Let’s get something straight, here; it is not difficult to see why modified cars and their drivers are often about as welcome as a bowl of fish eyes on the dinner table, and Fast and Furious glorified much of what the mainstream populace hated. The modified car culture had an anarchic, defiant tone to it, which is one reason why the Japanese cars, that were often seen as underdogs to more established American and German rivals among enthusiasts and media alike, fitted the film so perfectly.

The reality is that growing up with modified cars, and revelling in the lairy ridiculousness of the early Fast and Furious films and the Japanese cars that starred in them wasn’t just fun; it built a great respect for cars, how to drive them, and also for the owners and engineers that make them so special, whether they were factory-fresh or a muddled aftermarket mosaic.

My car-loving mates had all sorts of weird and sometimes woeful cars, from a Renault 19 (now ideal fodder for Unexceptional Classic status) to a Honda Civic Type-R, and we’d gather regularly in car parks to sit around, talk and generally put the world to rights, one oversized exhaust at a time. We didn’t even go for crazy joyrides, or circle town centres repeatedly.

We were perfecting heeling-and-toeing when we were 18, figuring out grip limits, feeling our way with cadence braking and more. You had to if you wanted to impress your mates and pretend that you were Colin McRae – which we all did.

My Celica represented freedom of expression as well as official entry to the performance proper JDM scene

Rude as the JDM and modified car scene seemed, those of us who were part of it were mostly just car geeks like all the other less outwardly-offensive automotive bubbles. Some might choose to clean wire wheels of a weekend, we chose to stick LEDs on the underside of our RX-7s. I mean, come on, it looks so cool that we’re all still doing it these days, just to kitchen islands rather than cars.

When I found myself at 21 and with an unexpected chunk of money to spare, there was no question that the car was going to be Japanese and fast. With Imprezas and the like still out of my price bracket, I found the car of my dreams (and my budget) in the ST185 generation, Toyota Celica GT-Four. Mine was a Japanese import, finished in gunmetal grey, that had been tastefully modified with adjustable dampers, aftermarket alloys, a rudely noisy dump-valve, an exhaust that set car alarms off, and manual control for the turbocharger which meant I could turn the wick up by around 50bhp, to some 250bhp. Now I could pretend to be Sainz, with cunning turbo tricks and all.

For someone who had just graduated from a Mk1 Nissan Micra, as well as BA Hons in English Literature, the Celica represented freedom of expression as well as official entry to the performance proper JDM scene.

It embodied everything I loved about Japanese cars, from its giant-slaying performance for a fraction of the cost of most of the alternatives, to its roots in WRC. And with sensible considerations in mind, there was even a healthy owners club network that I got involved with.

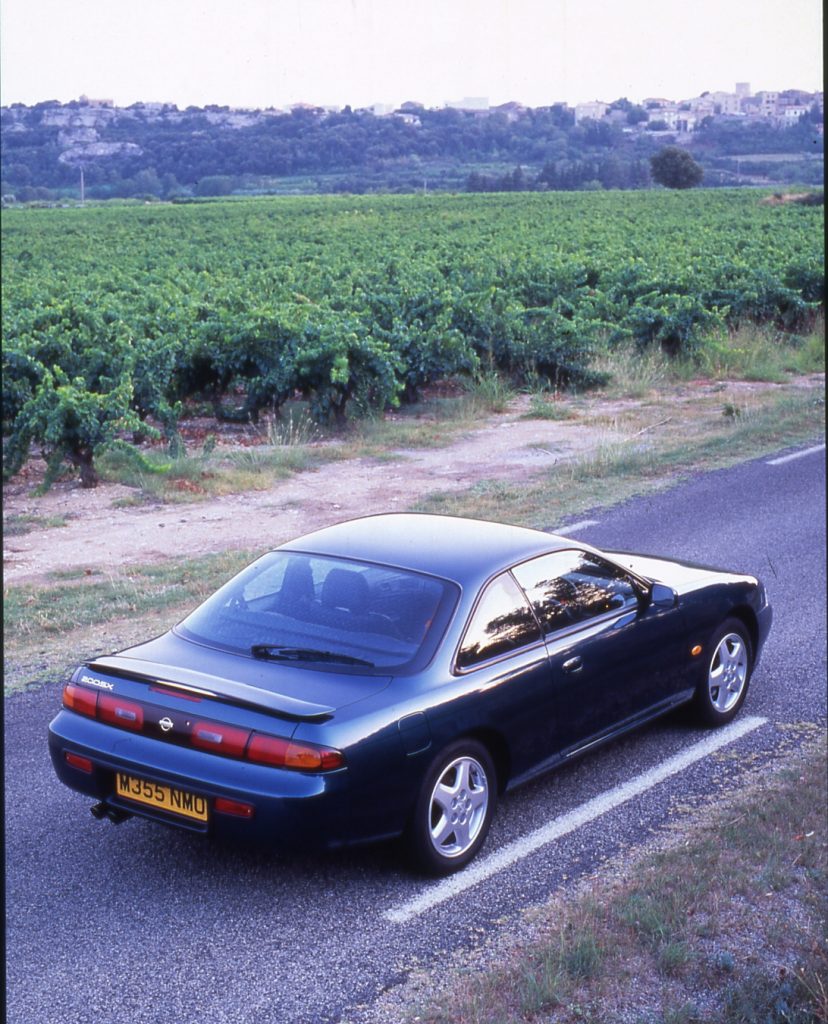

My Japanese car fandom only increased as I started my first job at Autocar magazine in 2006. Some of my peers on the title had also gone down the modified car route, with various Nissan 200SX variants (modified for better driftability and credibility, of course) being popular. And as I worked my way from a job with the picture desk to the road test desk, I was being handed keys to cars like the Mitsubishi Evo VIII and IX, frog-eyed Imprezas and more. Halcyon days, indeed.

But by that time, modified cars were being risk-assessed out of existence by the insurance industry, and Japanese car culture was maturing, turning its back on big wings and bigger turbos, forgetting homologation-special performance saloons, and instead focussing on profitable SUVs. When Subaru departed the World Rally Championship in 2008, it seemed to ring the last call for the gleefully obnoxious, bombastic JDM cars and culture that had given me such joy over the preceding decade.

It’s a culture built out of camaraderie and a healthy dose of railing against the establishment

The enthusiast scene is unrecognisable today from what it was as a millennial JDM fan, yet the roots are still there. You can see it in demand for the real stars of the original scene. Just try and find a manual, bi-turbo Toyota Supra for sane money, or an R34 Nissan Skyline GT-R for that matter.

So here’s my point; modified cars weren’t (and aren’t) bad, and nor were the people that drove them. It’s a culture built out of camaraderie and a straightforward love of caricature cars and people alike, finished off with an unnecessary bodykit and a healthy dose of railing against the establishment.

And I believe that the scrappy, underdog attitude of the JDM scene has never gone away. In fact, with the advent of the extraordinary R36 Nissan GT-R – now more cult than car – and even cars like the latest Honda Civic Type-R models, it feels like the JDM performance scene can still stick one finger up to the establishment. I mean, who ever expected Nissan to turn up with a £60k car that was faster – and in many ways better – than a Ferrari? That outright ambition to upset the automotive elite is still what defines the long-lived GT-R today.

You could argue I view JDM cars with a strong sepia filter; that as such a strident and defining part of my own youth, it’s inevitable I talk them up. But to those of us who love them, cars are a personal thing. The ones you’ve owned, the ones you covet, and especially the ones that shape your friendships and spare time so that, in the end, they actually come to define you.

Plenty of automotive genres do this, even now – it’s one of the wonders of cars in general. But I suspect very few have done it as strongly as the JDM scene, and the modified culture that it was an intrinsic part of. Rude and rebellious it may have been, but ultimately it was still just as much about comradeship and human achievement, as about how fast, and how furious the cars were.

Are you a fan of Japanese performance cars? Which have you driven or owned? Share your experiences, in the comments, below.

Vicky not quite as fast as yours but I have or I am on the 2nd miata which of course is the Mazda MX-5 Eunos version from Japan. Minimal rust hopefully and extras like air conditioning as standard the car car car has been modified slightly but still handles as it should and puts a smile on my face. Vinnychoff

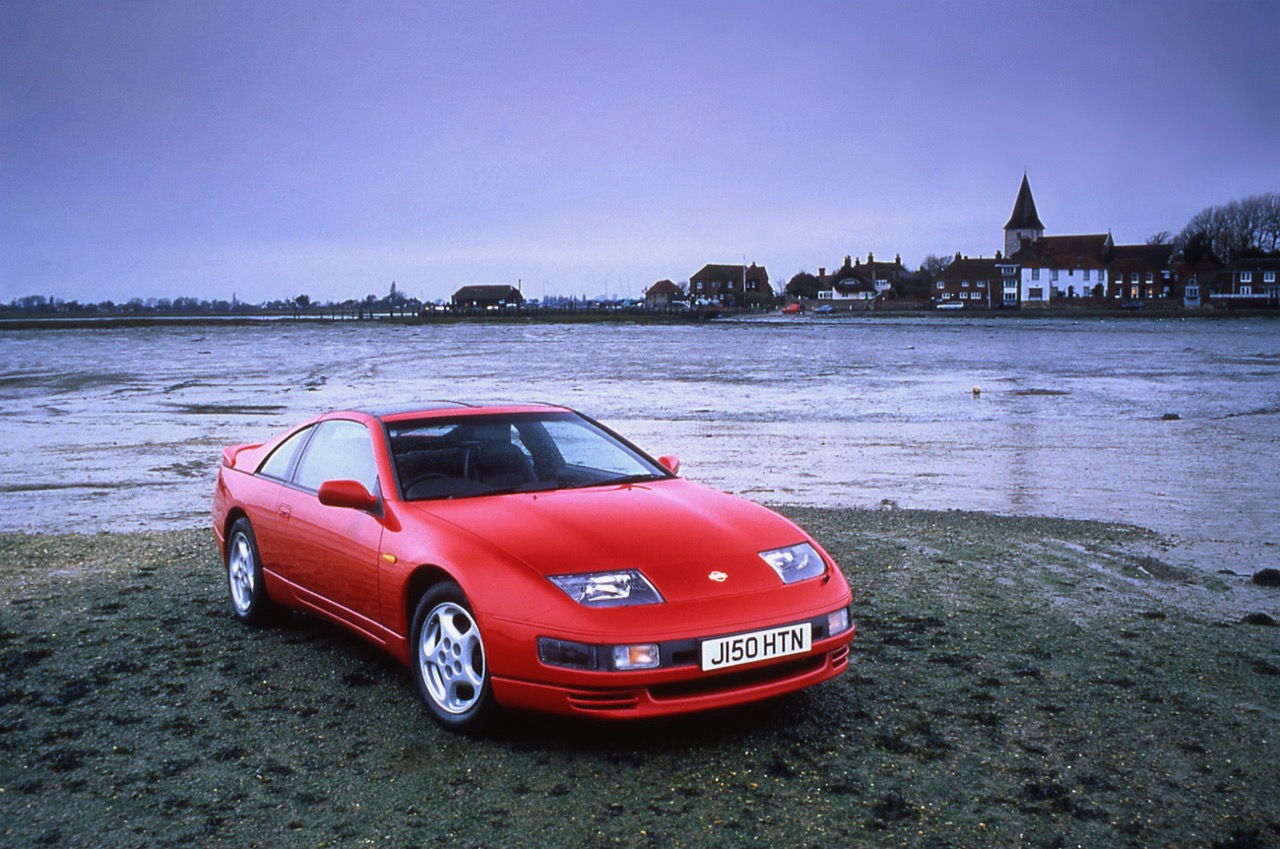

Sitting here in my R35 Gtr and smiling.. I have a 90 300zx and a 79 280zx in my garage ..these cars have a beauty that modern cars have lost ..

Growing up (or at least getting older) with these and owning quite a few you mentioned, I fondly remember the old meets and social activities. The scene is still alive but not as public. More the enthusiasts building in garages and knowing each other rather than strangers in a car park. It’s matured and developed with the times.

Although I still wonder why Hagerty, when I called for a quote, told me that my 1994 Evo 2 “isn’t a classic car”. Oh well.

Hi Terry, without getting into underwriting technicalities, much may have changed since that call. Would you like me to organise for one of the team to contact you? Happy to help, should you wish. Best wishes, James Mills, Editor.

Well I’m lucky to have a super turbo manual,best investment I made