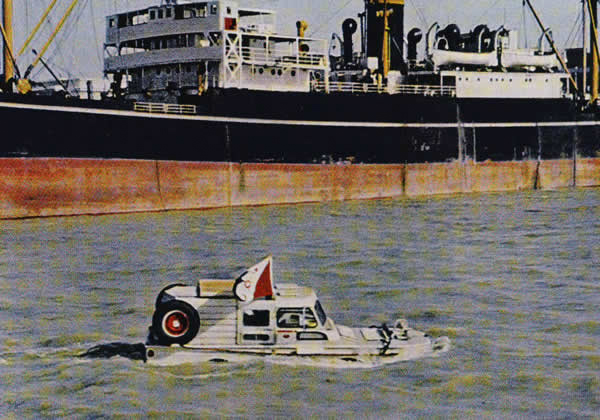

On the 23rd of January, 1956, a weary and battle-scarred sea monster unexpectedly clanked into the southernmost city in the world. The people of Ushuaia, Argentina, were so delighted that they threw a party. They even gave it a licence plate with the number 1 on it. The sea monster responded in kind by giving most of the children of Ushuaia rides around the harbour.

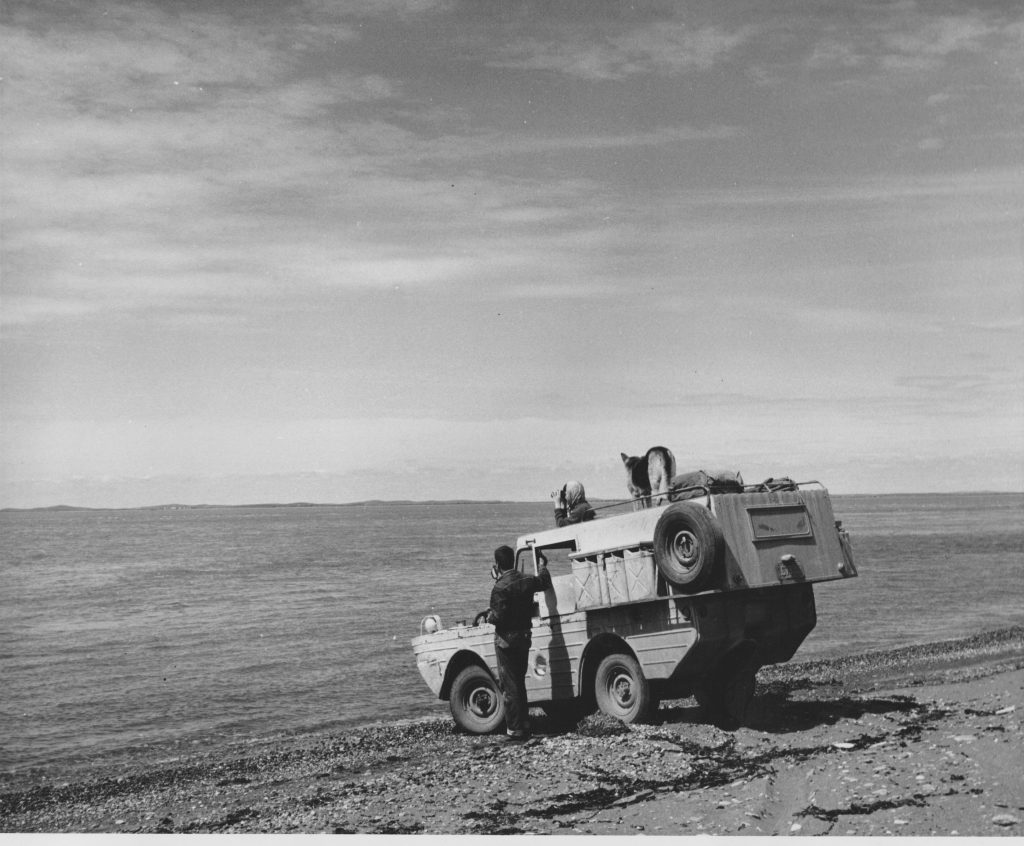

That monster was La Tortuga, Spanish for turtle, and it was the first motorised vehicle to arrive under its own power to this most southerly place, next stop Antarctica. A war surplus amphibious Ford GPA “Seep,” it had incredibly made its slow, laborious journey all the way from North America, its three passengers starting out in the Arctic Circle in Alaska, some 20,000 miles away. The adventurers had battled jungles and high mountain passes, scurvy and tropical illness, crashed through breakers and navigated recklessly driven caravans, and endured mechanical failure and endlessly snarled bureaucratic red tape. One of them was a dog. This is their story.

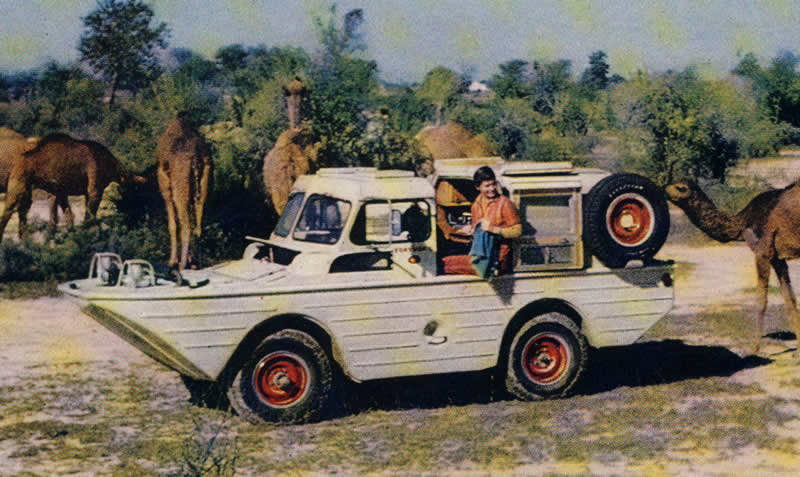

Helen and Frank Schreider are today both members of the vaunted Explorers Club of New York, peers of Neil Armstrong, Teddy Roosevelt, Jane Goodall, and Sir Edmund Hillary. They travelled the islands of Indonesia and the Great Rift Valley in Africa, sailed the Ganges by amphibious Jeep, and found the source of the Amazon River. Their adventures were published by National Geographic, the Saturday Evening Post, and in a series of books.

However, when they first set out on the long, arduous trek to Ushuaia, they were a newly married couple with an insanely ambitious idea of what a honeymoon trip should entail. Frank was a Navy man, working in submarines during WWII, and he and Helen met as students at UCLA after the war. They married in 1947, and four years later, with studies concluded, Frank swapped his Oldsmobile for a Jeep, and the pair headed off to explore South America. They only made it as far as Costa Rica.

That might have been enough of an adventure all by itself, but there was something restless about Frank and Helen. As the main obstacle that had flummoxed the first trip was an impassable mountain range, for the next effort, the Schreiders reasoned that if they couldn’t go through, they’d go around. After much searching, they found a war surplus amphibious Jeep, and began fixing it up.

The Ford Government “P” Amphibious (GPA) could not have been a more unlikely choice as a vehicle to try to be the first to reach the southern tip of Argentina under its own power. The nickname of Seep wasn’t just meant to mean “Sea-Going Jeep,” but was also a knock against its actual seaworthiness. They were created as a command vehicle for squadrons of six-wheeled DUKWs, like those made famous for Boston’s “duck” tours, but had very little freeboard and could be easily swamped by waves. Top speed on the water was just about 6 knots, or 7 mph.

Further, the GPA was 3500 pounds before you so much as threw a spare pair of socks in it, and propelled by a 60-hp 2.2L engine. On land, it was far slower than the Willys and Ford Jeeps on which it was based, and was arguably more likely to get stuck fording shallow waters.

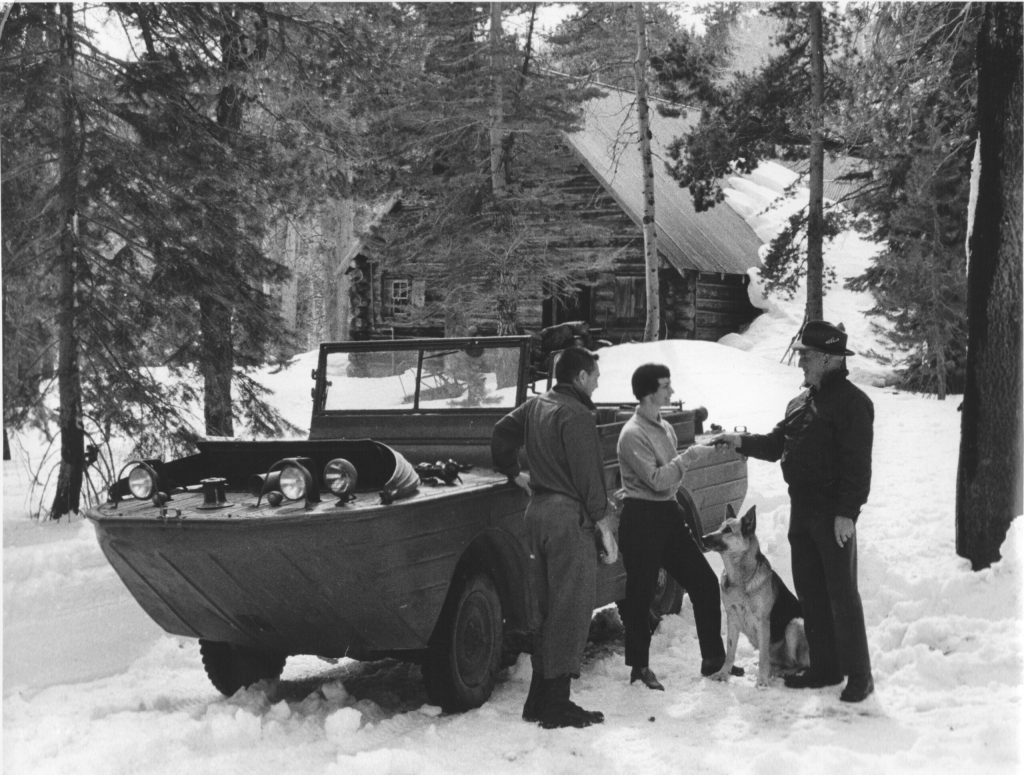

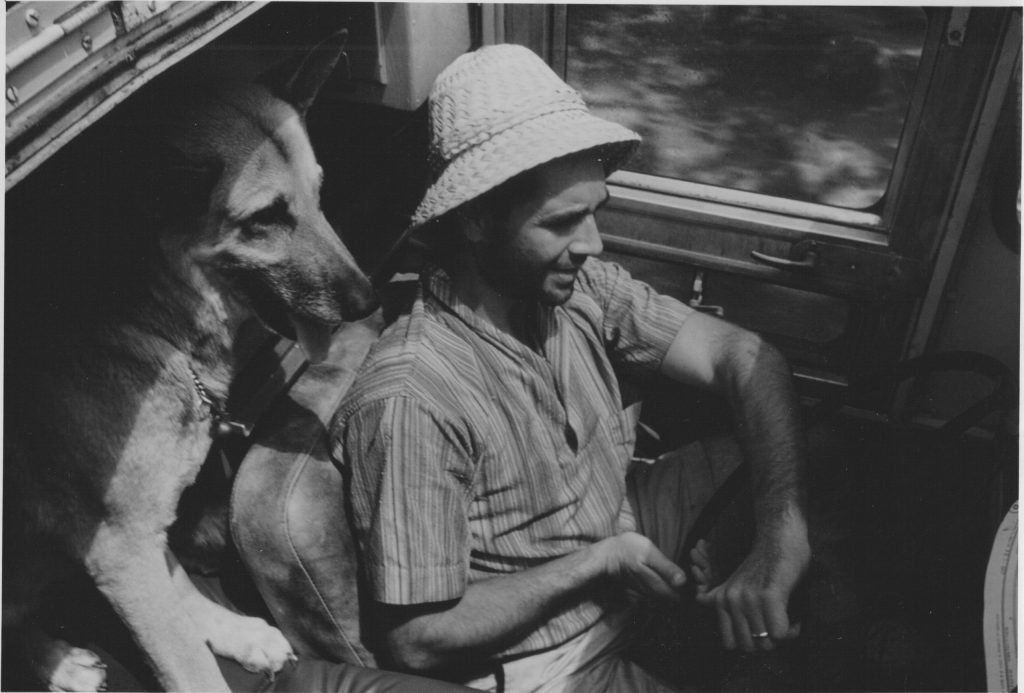

However, the one big advantage the Seep had, at least as far as the Schreiders were concerned, was that it was mechanically very similar to a Jeep, and WWII had ensured that parts for Jeeps were to be found pretty much everywhere around the world. Helen and Frank went to work for a couple of years in Alaska to save up money for their trip, then outfitted the GPA with a waterproof canopy with bunks and storage compartments. They packed it full of supplies, christened the vessel La Tortuga with a smashed Coca-Cola bottle, and, along with their German shepherd, Dinah, they hit the road. They left Alaska on June 21, 1954, the longest day of the year in the Arctic. The second leg of their journey, from California to Ushuaia, would take more than a year.

The log of that trip, written by Frank with artwork by Helen, is an adventure story that stands alongside the likes of Kon-Tiki by Thor Heyderal as a tale of refusing to quit in the face of seemingly overwhelming adversity. Their story, 20,000 Miles South, can be found for your e-reader, in used paperback, or via electronic library—it’s a great read and highly recommended.

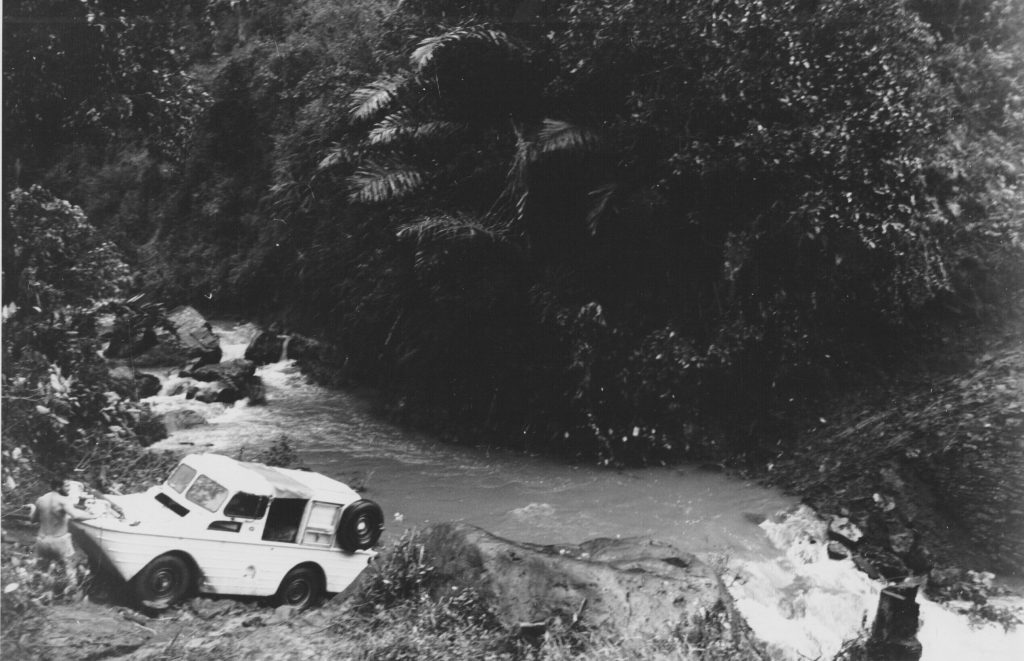

Even though you know the Schreiders are going to make it, the stories of La Tortuga nearly floundering in the first breakers in Costa Rica or shuddering to pieces when being driven on railway line on the way to Panama when no other roads were available is nail-biting stuff. Their route followed the Pan-American Highway for most of their journey, but much of the road was not completed at the time, and La Tortuga often had to make its way across swamps, down cattle tracks, and across oceans and lakes.

Unsurprisingly, it broke – not infrequently, and often in some of the most desolate places in the world. Luckily, Frank’s training as an engineer helped him patch together La Tortuga time and again, often with baling wire fixes and scrounged parts.

If done today, the Schreider’s expedition would have included Instagram updates, maybe a YouTube channel, and access to the outside world via satellite phone and internet connection in every major town. In the mid-1950s, it was self-reliance and occasional letters home to let family know that they were still alive.

But the story isn’t only a tale of self-reliance. Along the way, the Schreiders received help from everyone from the indigenous people of the Kuna Yala islands to the Admiral in charge of the Panama Canal Zone. Not everyone was friendly, and there were many instances where La Tortuga was travelling through countries dealing with political upheaval (their travel through Argentina came just months after a successful coup ousted Juan Perón). But for the most part, people were charmed by the Schreider’s adventurous spirits, and on more than one occasion, Dinah proved to be expert at diplomatic canine relations.

After an extremely hairy crossing of the Strait of Magellan, the joyous welcome of the people of Ushuaia, and a lucky lift back to Buenos Aires via a naval vessel, the Schreiders embarked on a speaking tour of the U.S. Their story was picked up and published in serialised and book form, and National Geographic came calling with freelance work. Later, NatGeo would hire them full time, sending them on expeditions throughout the 1960s.

That relationship ended in 1970, when National Geographic’s editor refused to concede that the Amazon was a longer river than the Nile, as the Schreiders most recent expedition claimed. They were later proved right.

Frank and Helen later divorced, and their careers took them in different directions. Frank joined the U.S. Foreign Service in Mexico, and Helen went to work for the National Park Service as an artist and designer of exhibitions. She received a presidential award for her work on a bicentennial exhibition in the Statue of Liberty.

Originally, when the Schreiders returned from their voyage to Ushuaia, only Frank was made a member of the Explorers Club—women were not permitted to be members. But, in 2016, she was officially inducted by Faanya Rose, the first female president of the Club. She was 89 at the time.

Amazingly, thanks to a small but enthusiastic community interested in GPAs and other military vehicles of WWII, the original La Tortuga resurfaced in 2006. A restoration may be in the works.

As for Frank and Helen, they came back to each other in the 1990s, sailing around the Greek islands in Frank’s sailboat, the Sassafras. Frank died in 1994 on that boat after suffering a heart attack, but Helen is still alive today, living in Santa Rosa, California, where she still paints.

Helen’s story, including the photos and film footage that the Schreiders took on their trips, is being put together by filmmaker Anna Darrah, who produces and directs for Film Nest Studios, the production company she co-founded. She says the Schreiders’ story isn’t just about their daring expeditions, it’s also, ultimately, a love story. Out into the unknown they went, a young married couple and their faithful Dinah, their small and amphibious Jeep swimming against the current, always looking for the next adventure.

I notice that half the photos show the cabin with a vee split windscreen and half with a flat single piece screen, and other differences. Just wondering – before I hunt down a copy of the book – if this is explained? Great story that I haven’t heard of previously. Read a great Jeep story years ago about 2 ex-army men buying an ex-army Jeep in Burma and driving it back to UK. Can’t remember the details and so far Google has failed to supply!

Helen Schreider has died (Feb 6, 2025). May she rest in peace after so much travelling!

The vehicle shown in the photo with the elephants is Tortuga II, a vehicle they evidently built later on and used on their trip to Indonesia, it seems. La Tortuga has one spare wheel, and a cantilever section over the back to accomodate the bunks. The first one is the one they used doing the trip from Circle to Ushuaia.

I’m saddened to hear that. I was very surprised to read in the article that she was still alive at the time of writing. I truly hope the recovered Tortuga is restored completely and put in a museum somewhere, maybe even the Smithsonian.