A 1967 Shelby GT500 is rarely the polite one in a crowd, but this is no ordinary crowd. Its big 428 turns over like King Solomon turning over in his bed, issuing a few basso grunts before settling down to a breathy burbling. It plays it cool, boy, speaking softly while carrying the proverbial big stick. On the other hand, a 1967 Lamborghini Miura P400 sounds like it’s giving birth to a chainsaw, sideways. Ululating through short, fairly straight pipes, its V12 goes Brap! Brap! Brap! Braaaap! Braaaaaaaap! There is smoke. There are pops and chortles and the figurative ripping of bodices. A Miura couldn’t be any more dramatic if its 350 horsepower came from 350 actual horses hitched to its bumper.

Horsepower. It is nothing but a cold, soulless calculation, a formula that divides work by time and measures not the power of equines, as its name suggests, but the power of machines. Horsepower doesn’t care how it is made. It has no biases; it worships in no particular church. You can make it with a rocket or a twisted rubber band, it doesn’t care. All horsepower needs to thrive is kinetic energy and a task against which to apply it.

***

Some 57 years after they dazzled the world, the Lamborghini Miura and the Ford Mustang Shelby GT500 still crackle with kinetic energy. We brought them together in the hills behind Santa Barbara, California, to celebrate the gloriously divergent ways in which engineers once made the big juice. Why these two cars? Well, thanks to a couple of generous Hagerty members, they were available. Also, the Miura was rated at 350, the GT500 at 355, but despite that one important element in common – plus having four wheels – they are about as similar as a cat and a cuttlefish.

Why 1967 in particular? As our colleague Jay Leno has astutely observed, that was the last year of complete automotive freedom, the last year before federal safety and emissions regulations began placing real limitations on design and engineering. Yes, there were state-by-state rules before that, such as on headlight size and placement – more on that in a moment – but 1967 was really the end of the libertarian automobile, the end of the unfenced West in the auto industry, and the beginnings of the plasticised, government-stamped, five-star-crash-rated eco-orbs we drive today.

And compared with today, the multitude of ways that horsepower was produced back in 1967 was incredibly diverse. The inline-six and the V8 reigned supreme in America, but carmakers globally were dabbling in everything from turbos to rotaries. At the 1967 Indianapolis 500, for instance, the starting grid included overhead-cam V8s, pushrod V8s, turbocharged fours, and a Pratt & Whitney turbine. In Europe, teams on the 1967 grand prix circuit were running inline-fours, V8s, V12s, and even an H16, which was essentially two flat-eights stacked on top of each other with two separate crankshafts, eight camshafts, 64 valves, and approximately 9000 ways to blow up.

Around the same time, a former Texas chicken farmer named Carroll Shelby had proved the reliability and potency of Ford big-block V8s in 1966 by employing pushrod, single-carb 427s to trounce Ferrari and its high-strung V12 wailers at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Between the Le Mans victory and all the 427s that Shelby had shoe-horned into AC Cobras, a big-block was a natural for his next Mustang-based model. However, the 427 was an expensive racing mill, with a much shorter stroke relative to its bore so it could rev, lots of internal reinforcement, and an appetite for oil at normal road speeds. Thus, for the grand tourer that Shelby envisioned the ’67 GT500 would be, he opted for what was basically a slightly bored and stroked version of the factory iron-block 390 that Ford offered in its ’67 Mustang. But to make doubly sure everyone made the racing connection, the GT500’s engine was given a name that covered all the bases: the Cobra Le Mans 428.

Derived as it was from a bone-stock 1967 Mustang, the Shelby GT500 started life as one long steel coil fed into mechanical shears and towering stamping presses in cavernous buildings whose opposite walls were barely visible from each other. Molten iron spilt out of huge buckets, welding sparks flew, and partially finished bodies trundled nose-to-tail down snaking assembly lines while armies of workers hurriedly fitted up parts. In the year that the ’67 Mustang was in production, Ford’s colossal factories churned them out at the rate of 54 an hour.

Specs: 1967 Shelby GT500

- Horsepower: 355bhp @ 5400rpm

- Engine: 7.0-litre pushrod V8

- Torque: 420lbft @ 3200rpm

- Weight: 3370 pounds

- Power-to-weight: 9.5lb/bhp

- 0-60: 6.5 seconds

- Price: $5500 (£1970)

Specs: 1967 Lamborghini Miura P400

- Horsepower: 350bhp @ 7000rpm

- Engine: 3.9-litre DOHC V12

- Torque: 280lbft @ 5500rpm

- Weight: 2850 pounds

- Power-to-weight: 8.1lb/bhp

- 0-60: 6.3 seconds

- Price: $22,000 (£7900)

Meanwhile, 6000 miles away near Turin, Italy, a Lamborghini Miura P400 began as a few small sheets of aluminium and steel pulled from a pile. They were trimmed and hammered and bent by dirty and calloused hands that welded and riveted each chassis one at a time between cigarette and espresso breaks that were animated by passionate discussions of Italian football. Leather was stitched and lathes were turned, and new Miuras came together at the leisurely rate of one about every two weeks.

As with the GT500, which Ford built and Shelby American rebuilt, the 743 Miuras produced over six years were likewise a team effort. The independent coachwork firm of Bertone assembled, painted, and trimmed the bodies, which were then loaded about four at a time onto trucks headed east to receive their transverse powertrains in a sleepy farming hamlet near Bologna, where a local tractor magnate had decided to play in the car business. Although the Shelby was considered pricey in 1967 at $5500 (£1970), a new ’67 Miura vacuumed a wallet of a breathtaking $22,000 (£7900).

The Yankee big-block versus the Latin screamer; which does 350 horsepower better? Well, it depends on how your tastes run. See, horsepower may be just a soulless calculation, but it can be all ate up with personality, as exemplified by the radically different engines in our two cars. Relative to the Lamborghini, the Ford 428 is one step up from the aforementioned twisted rubber band, a pushrod torquer in the classic style. Its greatest complexity is the pair of gold-tone Holley quads on top, each with a set of primaries and secondaries that when cracked wide open provide fully eight barrels and 1200cfm of breathing.

On its factory mild cam, the 428 idles lazily at around 700rpm and does all its best work between 2000 and 5000rpm. It’ll stretch to the redline at 6000 but is past its prime at that point. Digging out of holes is what the Shelby does best, and it’s capable of turning in 13-ish-second quarter-miles at over 100mph when you’re careful not to light ’em up. If you’re wary of smoking the (hilariously narrow by modern standards) E70-15 tyres, the car equally loves a gentler roll-on from a stoplight and a run through the long gears as the V8 bellows. You can merrily dispose of an entire Sunday doing that on all your favourite straight roads – though when curves come into view, there’s decent steering and brakes to work with and Shelby’s tuned suspension running adjustable Gabriel shocks.

***

Today, each surviving ’67 GT500 from the 2048 fastbacks built, especially David Farguson’s rare four-speed, commands a commensurately hefty price. Farguson, a retired car dealer, was nostalgic for the Mustang he owned as a kid and went searching for a so-called inboard ’67, meaning one with centre-mounted high-beam lights (“outboard” versions moved the high-beam lights to the sides of the grille to comply with some state laws regarding headlight separation). He pulled this example out of the Midwest as a rough but complete survivor and executed a flawless restoration about 10 years ago. The car crackles to life on the key and accelerates on a seamless tsunami of liquid torque as the engine spins up into a pronounced but somewhat polite roar.

The original Shelby Mustang, the 1965 GT350, had been a loud, clanking, stripped-down, souped-up track rat that barely met the definition of a usable road car. “It rode like a Conestoga wagon and steered like a 1936 REO chain-drive, solid-tire coal truck,” wrote the editors of Car and Driver, “and we loved it.”

Ol’ Shel quickly realised the path to greater riches ran through the bank accounts of wealthier clients, and those folks wanted plusher, more deluxe machines. Thus, the GT500 was added to the lineup for 1967, a car to stand above the GT350 in power, price, and amenities. New Mustangs arriving at the Shelby facility next to Los Angeles International Airport were stripped of their bonnets, boots, and front and rear sheetmetal. Affixed in their place was a kit of bespoke fibreglass components styled by Charlie McHose, a young Ford designer sent west in the summer of 1966 to shape the next Shelby. One reason GT500s are so valuable today is that they were the last Shelby Mustangs produced at Shelby’s own facility; for ’68, Ford moved Shelby production in-house.

Befitting a car based on a mass-market product from one of the world’s largest automakers, everything about the Shelby is friendly and functional. You slide into the flat seats through wide doors, and the instruments, from the speedo and tach in the centre to the auxiliary oil-pressure and amp gauges down by the shifter, are in plain sight. The car works just like any car that was engineered by college grads wearing coats and ties and tested to a fare-thee-well in all seasons and conditions for people ages 18 to 80 and sizes XS to XXL.

Then there’s the Lamborghini, a bare inch taller than the Ford GT40 that inspired it. Here are a few things that are odd about a Miura: The massive rear engine cover is hinged at the back and thus tilts rearward, so that if you don’t latch it properly, it blows open at speed and causes either horrific body damage and/or a crash. To open the engine cover, a separate T-handle in each of the doorjambs must be pulled out. However, you must remember to push the handles back in immediately or risk forgetting and slamming the doors into them, which bends both the handle and the door (no doubt after numerous complaints in many languages, later Miuras fixed this flaw).

To get into a Miura, first you stick your right leg in. Then you sit down on the sill. Then you slide your tush into the bucket. Then you haul in your left leg, being careful not to knock off the window winder in the process. To exit, as the old Haynes manuals used to say, simply reverse the steps. Unless you have a classically Italian shape, which is somewhat simian-like with short legs and long arms, the steering wheel will rub your bent knees as you grip it with bolt-straight arms. There is actually lots of room in a Miura cockpit (no doubt why a “friend” of Rod Stewart’s was famously able to press stiletto heel marks into the headliner of his Miura) but little of it is reserved for legs or feet as the steering wheel, dash, and pedals are all scrunched together at the base of the windscreen.

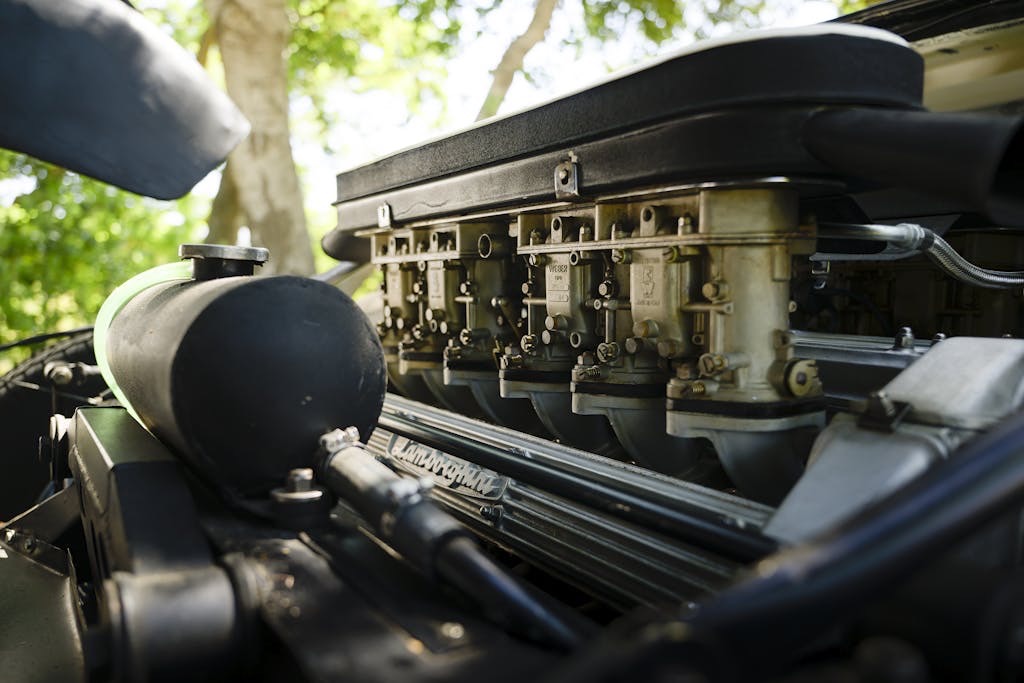

The all-important tach and the somewhat less important speedo – at least, less important to the Miura’s intended target audience of louche bad boys – look like two jet nacelles poking out of a flying saucer. Tracer lines of French stitching in the leather advertise the copious amounts of handwork in the Miura (the Shelby has these too, but they are fakes, moulded into the plastic dashpad). Behind your head, separated only by a pane of glass, stands a thick forest of Weber IDL downdraught carburettors, their fuel lines running mere inches from your scalp. Given the Miura’s hard-earned reputation for spontaneous exothermic combustion, aka engine fires, the term “driving with your hair on fire” is no joke in this car.

Against the 428, the Miura’s little 3929cc cast-aluminium V12 is a virtual tourbillon of frenetically moving parts. Double-overhead cams driven by separate timing chains for each cylinder head – each with their own helical drive gears, intermediate sprockets, and elliptical tension adjusters – means there are probably more parts in the Lamborghini’s valvetrain than in the entire 428. It takes a lot of oil to keep it all lubed and cooled; the Lambo’s sump holds more than three gallons, which it shares with its transverse five-speed gearbox.

Where the Shelby has two carbs, the Miura has four, each one with three barrels apiece. Meaning there’s a venturi, a throttle plate, a float, an accelerator pump, and an entire set of jets and emulsion tubes fuelling each of the 12 cylinders. All the carbs must be carefully synchronised to sing in tune, and a piece of dirt no larger than a pinhead can gum up the whole works, turning the Miura from a rampaging bull into a spluttering snail.

Where the 428 is all grunt, the Lambo is all opera. Running copious amounts of valve overlap for better breathing at high revs (and toxic exhaust fumes at idle), the engine doesn’t make its peak horsepower until 7000rpm. The seven-main-bearing billet crank is said to be good for 8000, but there’s no actual redline painted on the tach, which reads to 10,000. Considering that a set of engine gaskets alone – only the paper gaskets – is £1200, few owners regularly run their mills anywhere near the limit. Meanwhile, the engine’s torque peak of just 280lbft is at 5500rpm. In contrast, the Shelby’s output is 420lbft at 3200rpm, meaning what you have in the Lambo is basically a V12 motorcycle engine that is all shout and very little twist.

But that’s how the Italians did it –indeed, still do it (sort of) – Lambo using a short piston stroke of less than 2.5 inches to spin the hell out of the crank. And after one dip into the throttle, the attorneys for the defence can rest their case. Your ears, so close to those sucking, snarling intakes, are the two lit fuses on a massive dopamine bomb that detonates when the Miura starts raging up the revs. Ferruccio Lamborghini favoured V12s because, besides being manna for a dedicated showoff like himself, they are naturally balanced, offering both big power and nickel-balancing smoothness. But at a steep cost in complexity and, as any Lamborghini owner can attest, durability.

The car’s current owner was introduced to Italian exotics at an early age when his dad brought home a Miura back in the ’70s when they were merely weird, used oddballs. Now a retired university professor, he has owned two of his own, getting in before the prices went completely bonkers. His current car, an original yellow P400, is an early example, number 98 out of the 743 built between 1966 and 1972 (online you will see 764, but it’s now believed that 20 or so of these cars were renumbered at the factory and thus counted twice). The car – already sold to its first owner, Mitch Daroff, the CEO of the menswear firm Botany 500 and an avid off-road racer – was the star of the 1968 New York auto show. There are pictures of it being fawned over by leggy models in fluorescent miniskirts.

***

In places where the Shelby driver loafs, the Miura piloto is sweating through a Jane Fonda workout, manhandling the heavy steering, working the heavy pedals, grappling with the balky shifter. Don’t go for that gated stick unless you’re prepared; the Miura’s transverse five-speed gearbox is notoriously slow and unwilling to be hurried. Heated complaints about the shifting were one reason Lamborghini turned the whole powertrain 90 degrees in the Miura’s successor, the Countach, placing the transmission between the seats so that the shifter sprouted directly from it. We never did get a clean 1-2 shift in despite using all the rev-matching, double-clutching tricks. The owner says it upshifts best at around 5000rpm on a full-throttle run. Which tracks, it’s a Miura. With all that unfiltered mechanical mayhem at your back, it’s like driving a car while sitting between its cylinder heads.

How can these radically different cars make nearly identical horsepower? The answer lies in the calculation, which is work divided by time. The Shelby turns relatively slowly (peak torque at 3200rpm, remember) but can move a lot of mass, while the Lamborghini does its relatively paltry lift at a very speedy rate. Two ways of working the calculation to achieve the same number, give or take. And horsepower, that imposing figure upon which so many dreams are built, that divine idol to which so many have sacrificed so much effort and treasure, doesn’t really care how it’s made. And if we’ve learnt anything bringing these two circa-350bhp rock stars of 1967 together in such an unlikely pairing, it’s that their horsepower numbers are the least interesting thing about them.