It was 60 years ago this year that Malcolm Bricklin started to make his fortune, with a chain of hardware stores across the United States. Within two years he had sold the business to move into selling Lambrettas, then in 1968 he founded Subaru of America, to become the sole importer of the diminutive 360, the brand’s first car. By 1971 Bricklin had sold most of his stake in the Subaru business, having decided that it was time to fulfil his dream of putting his own car into production.

In 1972 Bricklin moved from Orlando (Florida) to Scottsdale (Arizona), to set up General Vehicle Corporation, to realise his dream of being a fully fledged car maker. Although he was born and based in North America, Bricklin reckoned that Canada was where he should set up his factory to build a revolutionary new plastic-bodied sports car. He targeted New Brunswick specifically, because high unemployment levels meant that he could secure a generous grant, courtesy of Provincial Government head Richard Hatfield.

The car that Bricklin envisioned would feature gullwing doors, a frugal small-capacity engine, and a steel cage that would headline a raft of safety features, including heavy-duty bumpers that would shrug off impacts. In June 1972 Bricklin drafted in Marshall Hobart to produce some usable designs for a car, the specification for which was constantly changing. Unfortunately, it wouldn’t take long for Bricklin’s dream car to turn into a nightmare…

The initial plan was to fit a four-cylinder powerplant, but discussions with AMC led to an agreement to supply 360ci (5.9-litre) V8s instead. One of these was installed in the prototype constructed by custom car builder Dick Dean, which he unveiled at the end of 1972. It wasn’t a runner, but this mock-up allowed Bricklin to raise funds to put the car into production, and with $950,000 secured for this, he set about poaching staff from The Big Three car makers (Ford, Chrysler, GM).

Over the coming months Bricklin hit the promotional trail like a man possessed. He was in the newspapers, on the radio, plastered all over magazines and on the TV. The interviews were relentless, but the result was an order bank for 2000 cars – and all this was before a running prototype had been built. At the same time Bricklin’s team was working feverishly on building four working prototypes, but things were not going well.

The biggest problem was the gullwing doors, but they were also one of the greatest selling points, so they had to be made to work. Weighing 90lb (41kg) each, they were electrically assisted, but if the car’s battery died the occupants had to climb out of the rear hatch. If the car was rolled there was no way of opening the doors, and sometimes the latches failed to open but the hydraulic rams would still try to open the doors, buckling them in the process.

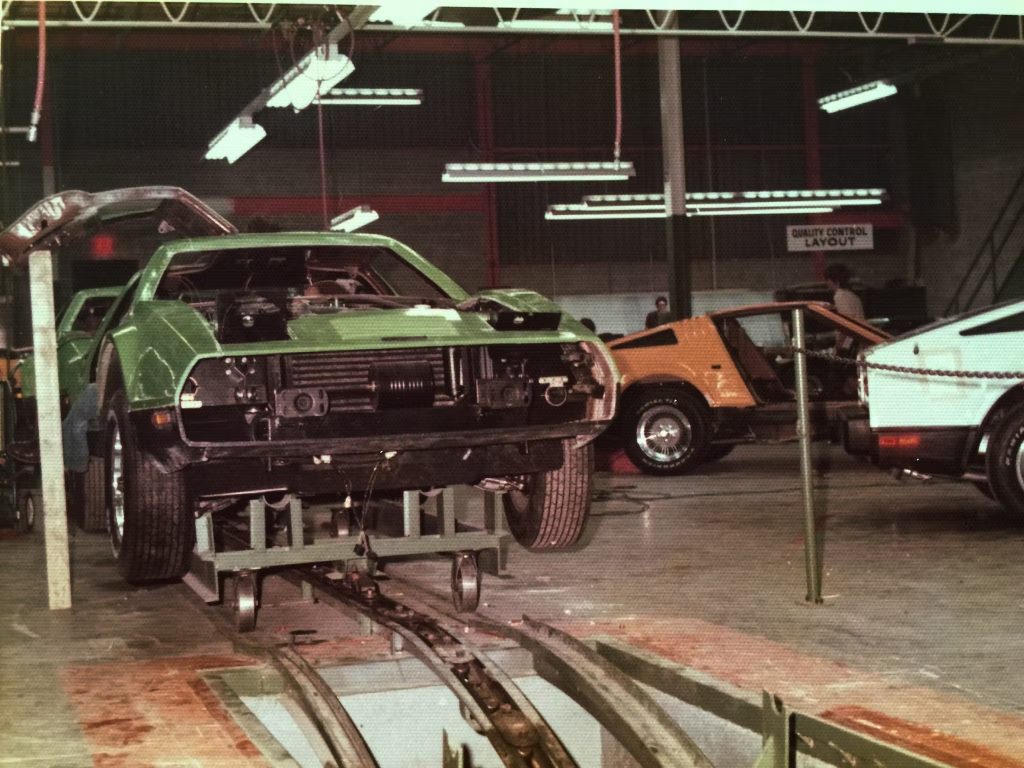

At the heart of the SV-1 (Safety Vehicle 1) was a steel cage, over which a series of glassfibre panels were draped, each covered in an acrylic skin that gave the car its (usually colourful) finish. This was new tech and one that Bricklin struggled to perfect, with extreme cold or heat likely to crack the panels. The production process was so poor that a quarter of the panels made had to be thrown away straight out of the moulds. Non-functioning pop-up headlights and windscreens falling out were other common glitches.

The first customer SV-1s started to trickle off the production line in August 1974, made by a team of 750 people who had never previously worked in car construction. But with the order bank now up to 4500, and with 247 dealers signed up, New Brunswick had to keep injecting more and more cash into the project to keep the factory going – even though the first cars were unsaleable because the list of faults was so extensive.

Available in five colours (red, green, suntan, white, orange), most SV-1s were ordered with a Chrysler three-speed automatic transmission, but a few were fitted with a four-speed manual gearbox. While all 1974 cars featured AMC’s 220bhp 360ci engine, for 1975 there was a shift to Ford’s 175bhp 351ci (5.75-litre) V8, which came only with a three-speed slushbox. Production limped into 1976, despite Bricklin going into receivership in September 1975.

Hatfield had originally agreed to invest $9 million in the project, but when Bricklin kept running out of cash he requested ever more backing. Pointing to the 4500 advance orders and 750 employees who could now feed their families, he secured $16 million in backing before the first car left the factory. By this point the SV-1 was priced at $7490 against a target cost of $5000, while production peaked at 420 cars in one month, whereas 1000 had been promised.

By the time Bricklin hit the buffers, the SV-1 was priced at $10,000 and New Brunswick was out of pocket to the tune of almost $20m. The dealer network had evaporated (despite each outlet having paid $8000 to sell the SV-1), thanks to the appalling build quality and a complete lack of support from the factory. Most of the dealers decided to just cut their losses and run.

With his company mired in scandal and debt, Bricklin stayed away from the automotive industry until 1983, when he took over the US distribution of the Fiat X1/9 and Pininfarina Spidereuropa. In late 1985 he set up Global Motors to import the Yugo; he then sold this company in April 1988 to leave the automotive world behind – for a while. But now aged 83, Malcolm Bricklin hasn’t given up on his dream to build his own sports car, having set up Visionary Vehicles in 2004. It’s planning to put a three-wheeled electric sports car into production, priced from around $30,000.

Asked in an interview why he originally decided to start a car company, Bricklin replied, “Because I didn’t know any better.” Ever the optimist, he still hopes he can fulfil that dream and make a success of building a car bearing his name.

Read more

10 hit and miss car features of the RADwood era

Your Classics: Bentley-beating luxury with Warren Christie’s Toyota Century

Owned 40 years and stored 30, this barn-find Aston Martin DB4 now needs some love