Citroën has never been afraid to go its own way, which is why it’s had more than its fair share of memorable cars – and bankruptcies – over the years. Ironically, the company was concerned that the car seen here, the GS Birotor, might lead to bankruptcy, so it tried to head off disaster at the pass – only to go bust not long after anyway . . .

Just four companies have ever put a Wankel-engined car into production – NSU, Mazda, Lada, and Citroën – although many more looked at the possibility of doing so. Back in the late 1960s, carmakers everywhere were embracing the idea of the Wankel rotary engine, which was seen as the way forward thanks to its inherent smoothness, flat torque curve, high power-to-weight ratio, low production costs, and compact dimensions.

Brands as diverse as General Motors, Porsche, Toyota, and Rolls-Royce licensed the patent, but by the early 1970s, it was apparent that the Wankel engine had serious flaws, with high fuel and oil consumption, worn apex seals, and high exhaust emissions all par for the course. The first rotary-engined production car was the NSU Spider, which arrived in 1964; three years later the NSU Ro80 was launched, and within two years NSU has gone bust because of warranty claims. Volkswagen-Audi took over the company and kept the Ro80 in production through 1977, although only 37,398 examples were made in that time.

Always keen to innovate, Citroën set up a joint venture with NSU as early as 1964 in order to develop Wankel engines together. Called Comobil and based in Switzerland, out of this grew another company in 1967: Comotor. This time the venture was created to manufacture rotary engines, and in 1969 Comotor purchased a vast plot of land and built a factory, so the two marques could churn out rotary engines for a new generation of family cars. The plan was that Comotor would become the go-to company for rotary engines, which would be supplied to a raft of carmakers.

Things started to go awry straight away, with NSU over-reaching itself. When the warranty claims started to flood in because of stricken Ro80s with engines that had failed in as little as 10,000 miles, NSU ran into the arms of Volkswagen-Audi. But Citroën was heavily committed and decided to continue anyway, unveiling the GS Birotor in September 1973, just as the oil crisis was about to hit. Hardly ideal, when your compact family saloon guzzles petrol at the rate of 18mpg.

Citroën’s plan was to build a rotary-powered CX, and below that would be the GS Birotor. Although the Birotor looked much like the regular piston-engined GS, very little was shared. Of the outer panels, only the roof and doors were common, and even the floorpan was substantially altered. The front and rear wings were different, as they featured more significantly flared wheelarches to accommodate beefier wheels and tyres.

Meanwhile, the metallic bronze paintwork and dark brown roof were unique to the Birotor, with all examples featuring this colour scheme. Effectively a halo model within the GS range, inside there were high-backed seats and plusher carpets, while there were also stronger brakes. Fitted with discs front and rear, the former were inboard to reduce unsprung weight.

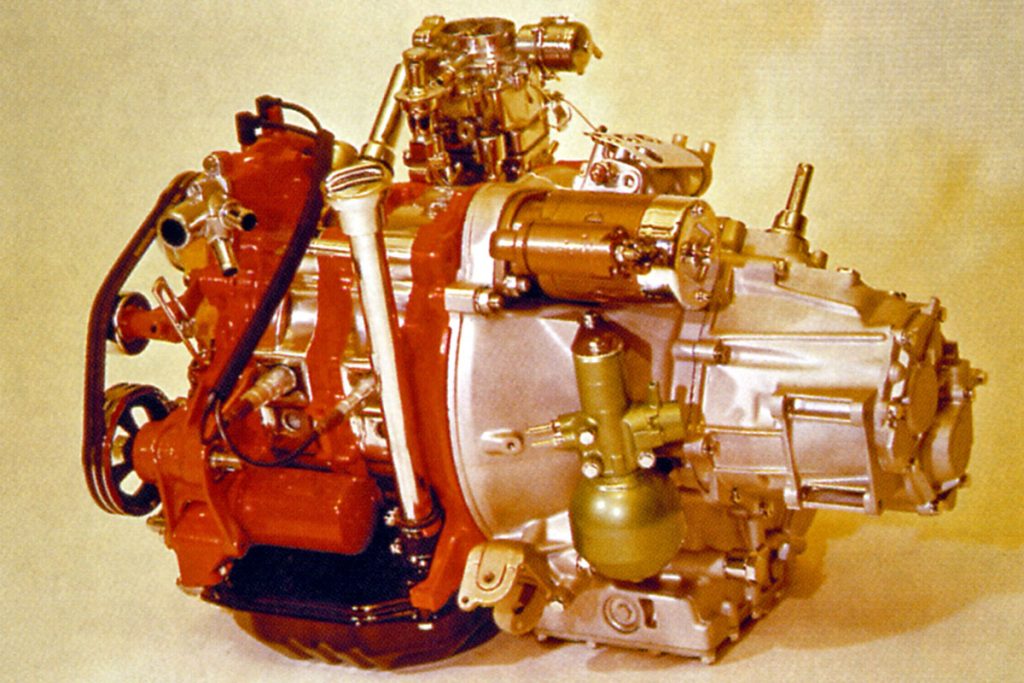

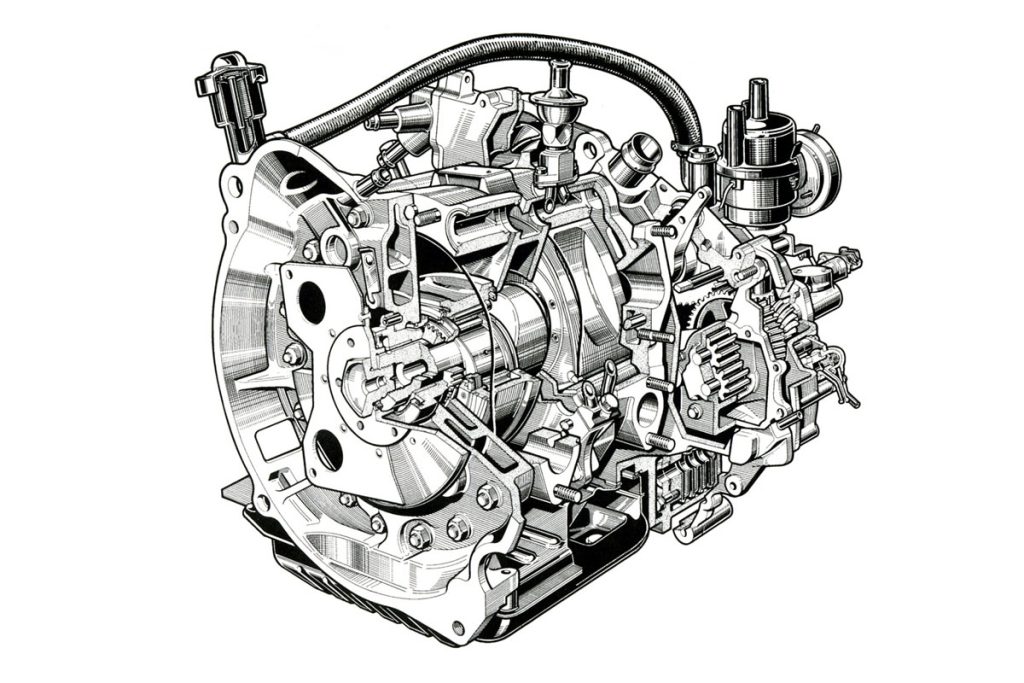

In the nose was a two-rotor engine with a displacement of 497.5cc, which in conventional terms was the equivalent of 1991cc. Fed by a twin-choke Solex carburettor, the engine put out 106bhp at 6500rpm, which was enough to take the aerodynamically efficient GS all the way up to 109mph. Torque peaked at 101lb ft at 3200rpm, and to make the most of this, there was a three-speed semi-automatic transmission that sent the power to the front wheels.

The GS Birotor was launched in mainland Europe in early 1974; UK sales were supposed to follow at the end of 1974. But by this point Citroën had got cold feet thanks to a combination of customer apathy (a 70 per cent price premium over regular editions meant it cost more than the bigger DS) and the spectre of poor reliability leading to massive warranty costs. Realising what potentially lay ahead, Citroën offered to buy back cars from customers to reduce warranty headaches, and so that it wouldn’t have to worry about maintaining parts supply.

Citroën even went so far as to withdraw the Birotor’s Type Approval, so that owners really were on their own if they chose to keep their cars rather than return them. But the huge cost of building the Comotor factory and also of developing the GS Birotor were too much, and in 1974, arch rival Peugeot acquired a 38.2 per cent shareholding in Citroën, which grew to 90 per cent in 1976. The result was the creation of PSA (Peugeot-Citroën) and far less innovation over the coming decades.

It’s not known how many owners sold their cars back to Citroën, but of the 847 GS Birotors made, just a handful are left. Some reckon as many as 200 have survived, while others say it’s just a few dozen. In April, auctioneers Gooding & Company sold one from the Mullin Collection in California for £17,905. Other examples reside in museums: You’ll find one of these curiosities in the Lane Motor Museum, and there’s another in the Isle of Man Motor Museum. Have you seen one lately?

I think you meant “arch rival” instead of “archival”? Maybe one day you’ll cover Lada’s Wankel engined cars.

Nice catch – fixed!