As early as May 1968, just as the Austin-Healey 3000 was being axed, Jensen boss Carl Duerr started a project to create an affordable two-seat roadster, powered by a BMW straight-six engine. Keen to retain Healey involvement, Duerr brought in Donald and Geoffrey Healey, who preferred the use of Vauxhall running gear. The result was a running prototype called the X500, which was fitted with a 1975cc Vauxhall engine. Unfortunately, the sole test car made was written off while testing in December 1970.

By the time the X500 had been destroyed, US-based British sports car importer Kjell Qvale had got wind of Jensen’s plans and he muscled in on the project, with a view to making a ton of money from selling the new car in the US. Compared with the X500, Qvale proposed a complete redesign, and knowing that this was a car created largely for American buyers, and its success would be dependent on Qvale’s support, he held a lot of sway in the decision-making process. The result was a roadster that was much more current in its appearance, with Coke-bottle hips and recessed circular headlights.

One of the key problems with the new sports car, however, was that the Vauxhall engine didn’t produce enough power breach the 100mph barrier. Jensen entered into talks with Ford and Mazda, but neither had the capacity to provide the 10,000 powerplants per year that were envisaged. For the same reason, BMW ducked out, but then Jensen seemingly had a stroke of luck: Two of its engineers were on a train discussing the project, when Lotus engineer Graham Arnold overheard. He joined up the dots for them and proposed that Lotus should provide a suitable powerplant. All systems go.

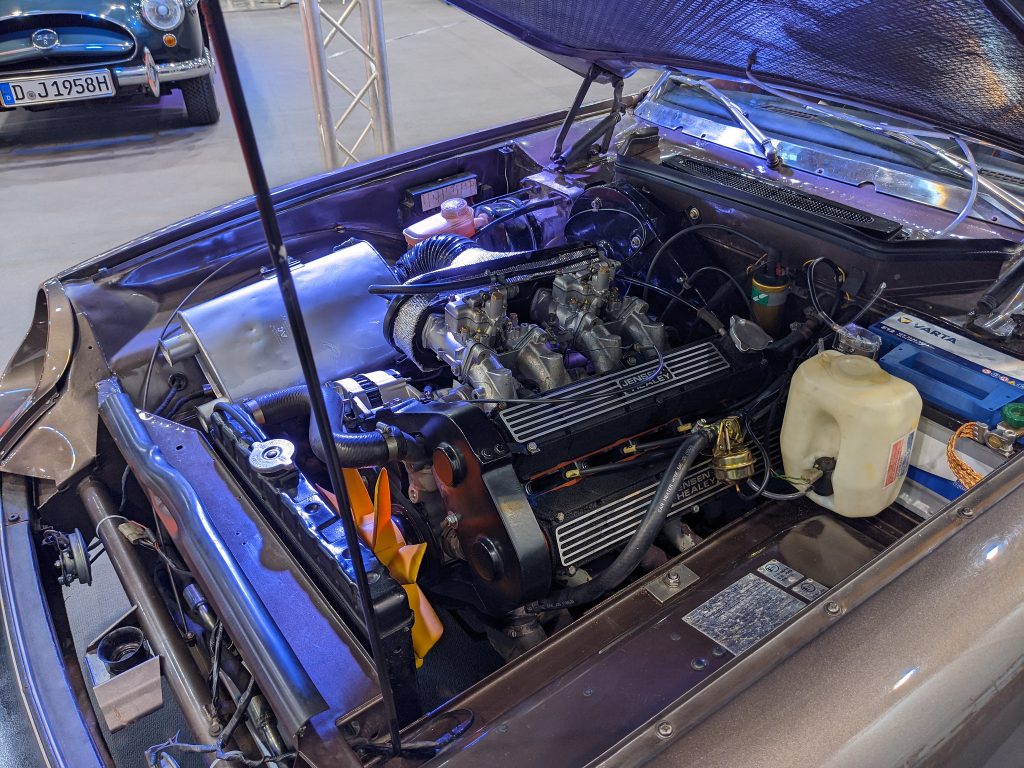

In March 1972, the new Jensen-Healey Roadster was unveiled at the Geneva Salon, powered by Lotus’ new twin-cam 907 engine, which had yet to be fitted to any Lotus. Unfortunately the unit proved to be hideously unreliable, and Jensen ended up having to finish off its development – after it had been fitted to the first customers’ cars. It was another one of those missed opportunities, because the Jensen-Healey brought with it the first British mass-produced 16-valve engine. But that’s the problem when you innovate…

Although the press was largely enthusiastic about the Jensen-Healey when it arrived, the tide soon turned when it became obvious that the most reliable thing about the car was its lack of reliability. The arrival of a Mk2 version in August 1973 ironed out some of the problems, but there were still many, and by now Donald Healey had walked out, dismayed by all the maladies. When the people in charge of the company start to walk away, you just know things are going badly wrong.

As time went on, the problems really piled up, with water-soluble bodywork, leaky roofs (necessitating a redesign), and never-ending engine glitches all par for the course. Production would limp on until Jensen went bust in 1976, but a year before that a new variation on the theme was introduced: the GT shooting brake.

Now all but forgotten, sketches for a Jensen-Healey estate car were circulating as early as 1972. But it wouldn’t be until December 1974 that the first prototype had been made, and customer cars wouldn’t be ready for another six months after this. By the time the smart-looking new sporting estate had been introduced, the Healeys had retreated and the car was marketed as the Jensen GT, still largely with the North American market in mind.

More than just a fixed-roof Roadster, the GT used the same floorpan as far back as the rear axle, but after that there were mods aplenty. The estate’s much stiffer structure meant less stiffening was required elsewhere, and fitment of air conditioning as standard to Federal cars meant the front bulkhead had to be modified. The roadster’s 92-inch wheelbase was retained, though, and with the overall length rising by just two inches, any weight gain was moderate (2400lb compared with the Roadster’s 2300lb). Thanks to a slightly higher centre of gravity, a rear anti-roll bar was added, while the suspension was stiffened and a bigger brake servo was fitted. Other than that, mechanical changes were slight.

Whereas the Roadster’s interior had been rather scrappy, much effort was put into poshing up the GT’s cabin, which received a walnut dash, higher-quality seat trim, and a four-speaker stereo. Optional equipment included leather trim, air conditioning, and various sunroofs; this was intended to be a cut-price Interceptor, but with the focus still on luxury. Its makers hoped that buyers would see the new arrival as a small Jensen rather than a fixed-head version of the Jensen-Healey Roadster.

Despite the Roadster’s well-documented litany of problems, those who tested the GT rather liked it. Autocar drove it in 1975 and started by pointing out that Jensen faced a very uncertain future, with bankruptcy highly likely. Just the thing to entice buyers to sign on the dotted line! Of course, things were not helped by a £4563 price tag, when the MG BGT V8 and 3.0-litre Capri were both priced at £3372, or you could have a Reliant Scimitar GTE for £3468. The Jensen’s load bay capacity sat somewhere between the MG’s and the Reliant’s.

Of its early GT tester, Autocar opined: “The Jensen is a qualified success. It is a fast, reasonably economical and comfortable car for two. Its hatchack design is a useful feature enabling large objects to be carried (though the rear seats are far too cramped for adults), and Jensen has made the GT quieter and more refined than the earlier Jensen-Healey. The engine is still too noisy when extended, though, and the car is not as quiet as the Lotus Elite which has the same engine.”

With the Jensen-Healey’s many glitches largely ironed out by this point, perhaps the GT could have been the car to save Jensen. But with the global economy wrecked, and companies of all sizes struggling to stay afloat, it was only a matter of time before Jensen went under. Selling new cars was hard enough, but paying for all of the Roadster warranty repairs had crippled Jensen, and in May 1976 the company shut its doors, after just 511 GTs had been made. Although more than 10,000 examples of the Jensen-Healey were built, and it is still recognised by classic car fans on both sides of the Atlantic, its tin-top sibling is all but forgotten, despite being the better car of the two.