We’ve all heard modern Vauxhalls being dismissed as ‘badge-engineered Opels’, but that certainly hasn’t always been the case, and the pretty little roadster you see here came from a time when the Luton company’s design and engineering facility was fully autonomous and, what’s more, an industry-leader in the UK.

General Motors had purchased Vauxhall in 1925, transforming it from a by-then unprofitable manufacturer of elegant, high-end sporting cars into a doyen of the mainstream by the start of WW2. Its design department also cut a swathe through the gloomy grey of Britain’s austere post-war car-design era with daring hints of Americana across Vauxhall’s range.

And the man responsible for the look of these cars was David Jones, a protégé of GM’s legendary Harley J. Earl. Already a Luton veteran, Jones was head of styling in the early 60s when Vauxhall launched its first post-war compact saloon, the Viva HA. While the HA’s appearance was uncharacteristically conservative, Jones saw potential to use its underpinnings as a cost-effective way of producing an affordable two-seat sports car to go head-to-head with the increasingly popular Austin Healey ‘frog-eye’ Sprite.

In these days of ever greater integration between sibling car companies, it seems strange to think that 60 years ago GM was actively encouraging increased autonomy of its largest non-US brands, Vauxhall and Opel. Which is why, despite the HA’s shared componentry, the Vauxhall Piper concept, as it became known, was conceived without Opel’s knowledge.

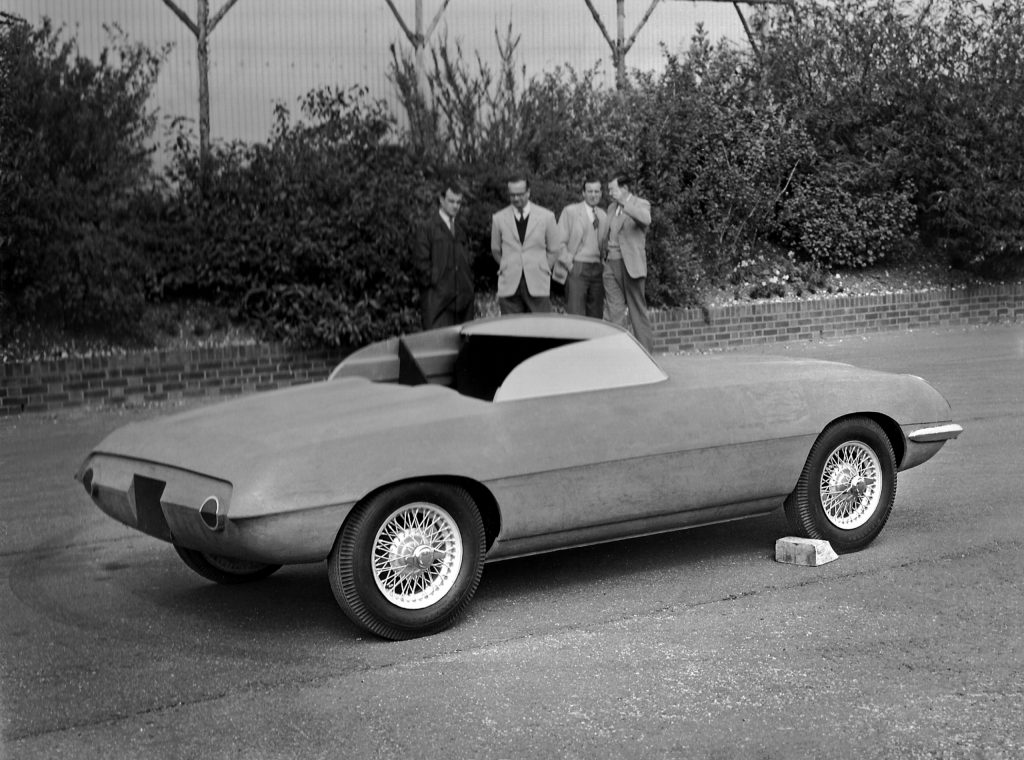

In just two months, the Piper’s first design sketch had grown into a full-sized clay with gratifyingly no resemblance to the boxy Viva. Its rakish, simple and modern shape, with overtones of Jaguar E-type and Chevrolet Corvette, had a purity that only an early concept car could ever possess. Nevertheless, parked next to the little Austin Healey, which had only been launched five years before, it looked like something from another era, so modern and fresh were its lines.

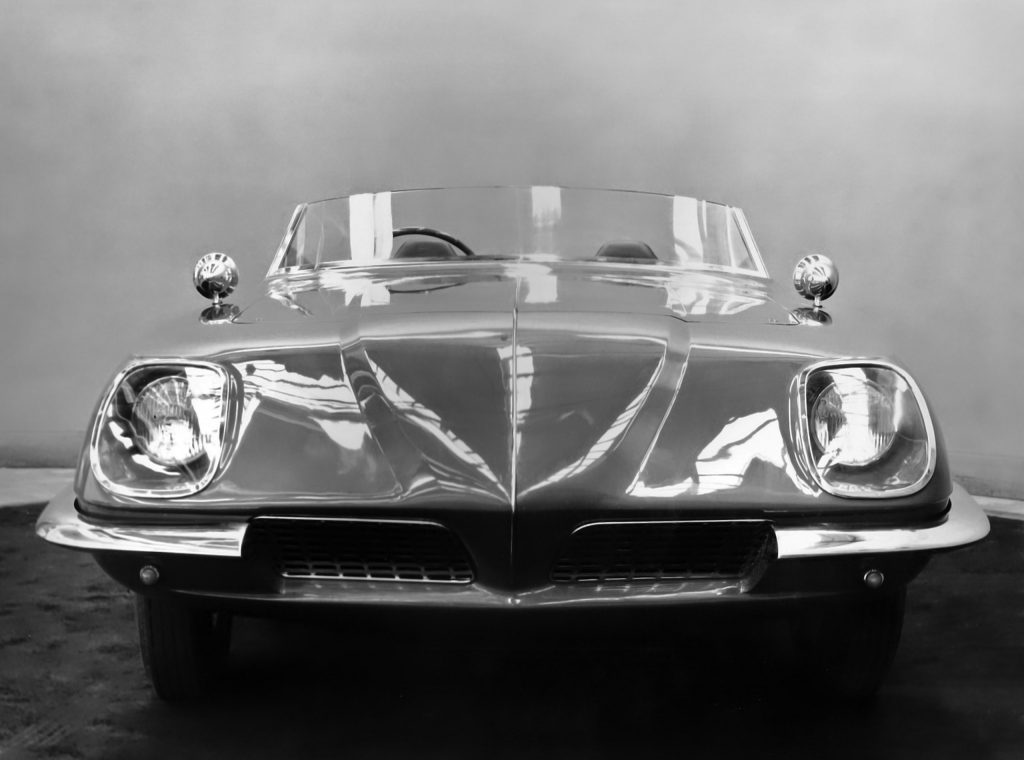

Of course, simplicity and purity are fine until you introduce essentials like a need for passenger/luggage space and an engine that offers sufficient performance to go with its looks. So, as you can see from the images here, the Piper’s second iteration, while more complete, was considerably more fulsome. Outside, its headlights were faired-in and the front grille had more than a nod towards the E-Type’s. The wire wheels were retained, but deeper, chrome-trimmed sill panels were added. From the rear sprouted twin exhausts, with no bumper, and to give the clay body extra lustre, a layer of synthetic Dynoc was applied. There was even a faux design badge, incorporating a re-drawn Vauxhall logo, a la those sported by Bertone and Ghia.

The Piper’s cabin was simplicity itself, though. Two ribbed-leather seats were mounted behind a clean, uncluttered dash with its main speedo and tachometer pinched from the new FB Victor VX4/90. A slightly over-large steering wheel was the only incongruous item, but even that conformed to contemporary design, its two spokes drilled for extra lightness.

Project momentum had really started to grow by this point. In August 1963, just three months after first sketches of the Piper had been drawn, with Vauxhall board’s approval Jones assigned a dedicated five-strong team to build a driveable prototype to coincide with a visit from GM’s vice president of design, Bill Mitchell that December. Naturally, myriad changes now had to be made to accommodate an engine, drivetrain, opening doors and a basic electrical architecture. The HA’s anaemic 1057cc motor wasn’t even an option to power the Piper, so the VX4/90’s 71bhp 1594cc ‘four’ was shoe-horned in to its engine bay, dictating a higher, V-shaped bonnet line, and conventional bonnet opening instead of the ‘clam’ design suggested on the clay.

Even so, there were so many other areas of the working Piper’s design that deferred to a more transatlantic influence, indicating that Jones was still very much governed by Vauxhall’s paymasters in Detroit. The styling around the front of the car – headlights, grille, quarter-bumpers – all appeared more aggressive, and overall the car looked bulkier. Either way, by the end of ’63 Vauxhall was able to register the car with the Bedfordshire number ‘281 NM’.

There’s no record of Mitchell’s verdict when he arrived at Luton, but senior management tested the car at the company’s Chaul End test track (alas, now a housing development) and loved it. So why it was then dismantled and the entire programme very quickly forgotten about is anyone’s guess. One can only conclude that low sales volumes would not have justified the development and production costs.

Vauxhall continued to build some extraordinary concept cars over the next decade (two of which, the 1966 XVR and 1970 SRV still survive). Its Engineering and Styling Centre (latterly the Griffin House HQ, only vacated in 2019) was opened a year after the Piper’s demise and was responsible for almost all Vauxhall models for the next two decades. And even some of the badge-engineered ones.

Read more

11 of Zagato’s greatest hits

How are cars designed? An industry insider takes us through the steps

1972 birthed a new angle for Italian sports cars