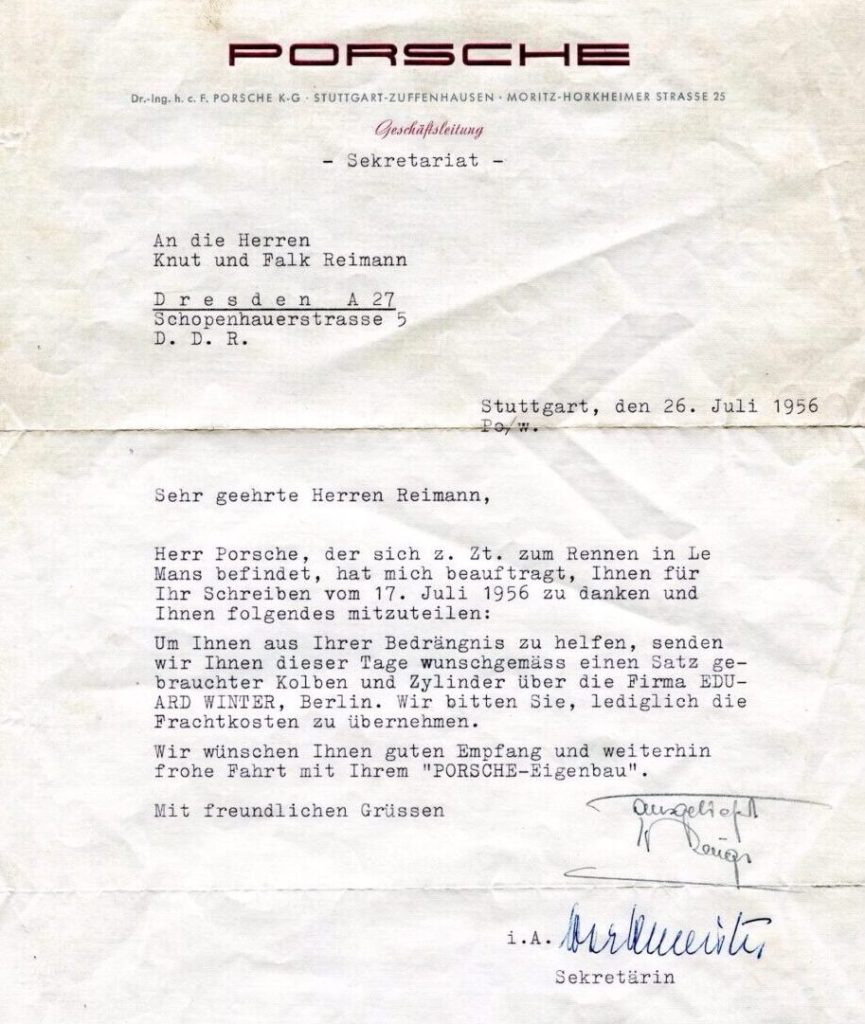

Nearly 70 years ago, a homely little coupe clattered up to the front gates of Porsche’s factory in Zuffenhausen, much to the bemusement of the company’s employees. At first, the workers were offended at this obvious fake; it looked like a 356, but the proportions were off, and the bodywork was hand-hammered. But resistance gave way before the infectious enthusiasm of the lanky twin boys who owned the strange car, and eventually a factory tour was arranged. Staff even promised to leave a note for Ferry Porsche, and a few weeks later, he responded in a letter dictated to his secretary from the pits at Le Mans.

“Wir wünschen inhen guten empfang und weiterhin frohe fahrt mit ihrem ‘PORSCHE-Eigenbau.’”

Rough translation: We hope you had a good reception and wish you a happy journey in your homemade Porsche.

Thus, Ferry himself had unofficially blessed perhaps the first-ever replica Porsche, and what’s more, he was going to send these two young enthusiasts original Porsche engine components so that they could make their car properly quick. All they had to do is smuggle those parts back to the place where they’d built it – over the border and into the Deutsche Demokratische Republik, communist East Germany.

Germany unconditionally surrendered to the Allies on May 7, 1945, and by 1949 the country had been split into the democratic Bundesrepublik in the west, and the socialist DDR in the east. Most modern depictions of the relationship between the two sides tend to fast forward through the 1950s, straight to August 1961, when the first bricks of the Berlin Wall were laid, the division writ large in concrete, machine guns, and barbed wire. There are some pretty good stories about the days after the wall went up, from daring escapes to smuggled-out Auto Union racers. But in that interim period during the 1950s, what you could get away with basically boiled down to how cheeky you were willing to be, and Knut and Falk Reimann were cheeky indeed. They were also unwilling to bend to the ever more repressive DDR rules.

After all, they had lived through hell. The boys were just 12 years old when Allied bombers attacked their home city of Dresden in one of the more destructive air raids of the war. Four waves of British and US heavy bombers dropped nearly 4,000 tons of high explosives and incendiaries on the city, levelling large parts of it and causing a firestorm. Immediately postwar, food and shelter were scarce, and refugees were everywhere.

Later, in an officially partitioned Germany, those trapped in the former Soviet sector couldn’t help but contrast the economic opportunity of the rebuilding in the west to growing stagnation in the east. The Reimann brothers, now in their early 20s, were both in engineering school, and they dreamed of owning a car like the new Porsches. The little sports cars were making a name for the company, beating the giants with deft handling and light weight. But even if you could afford one, importing one across the line was impossible. The Reimanns did the next best thing.

They’d learned some basics of auto mechanics by fixing up a war-surplus BMW motorcycle, and later a Fiat Topolino. The kernel of the idea came when they stumbled across the chassis of an abandoned Type 82 Kübelwagen, the VW-based basic transportation of WWII. The Type 82 was, after all, designed by Ferdinand Porsche, so what better place to start.

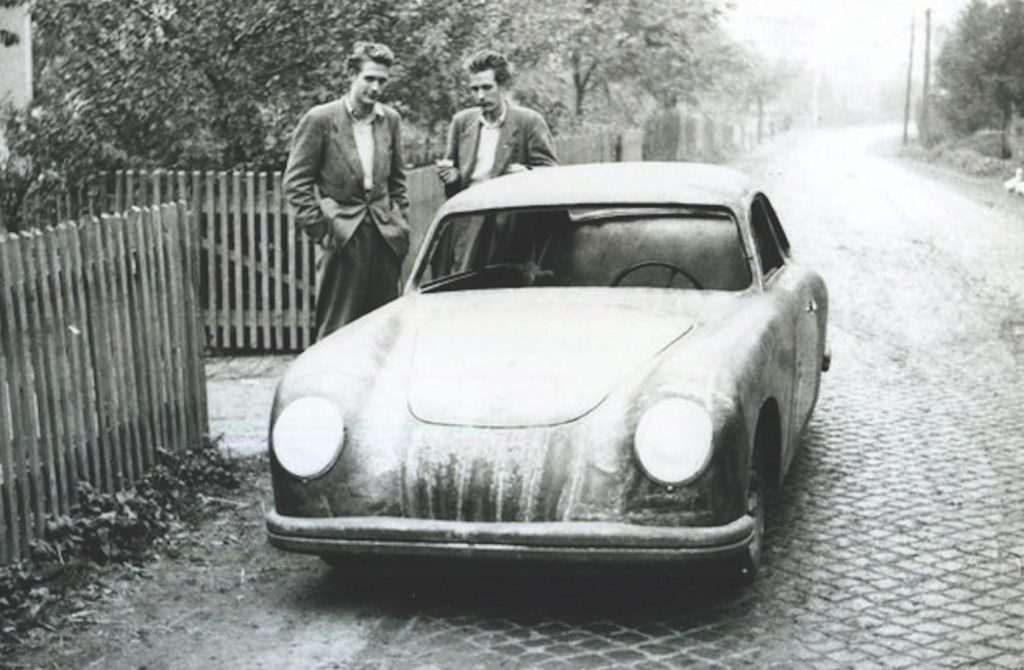

The brothers approached a Dresden coachbuilder named Arno Lindner, who was struggling to find a way to fit his family business into a changing world. The idea of producing a limited run of Porsche-like vehicles seemed like a niche that might work, so the Reimann brothers sketched out a design, and Lindner set about creating a structure that combined tubular steel and a wooden frame of ash. Sheet steel of any quality was exceedingly hard to find, but the Reimanns found a cache of old Ford trucks and hammered the body for their car out of 15 bonnet panels.

As it was based on a Type 82, the Lindner Coupe (as they would come to be known), was larger than a real 356, and the rudimentary construction made it heavier. But the earliest Porsche prototypes were hand-made, too, and arguably the brothers and Lindner put as much care and attention into their creation as the Porsche family had.

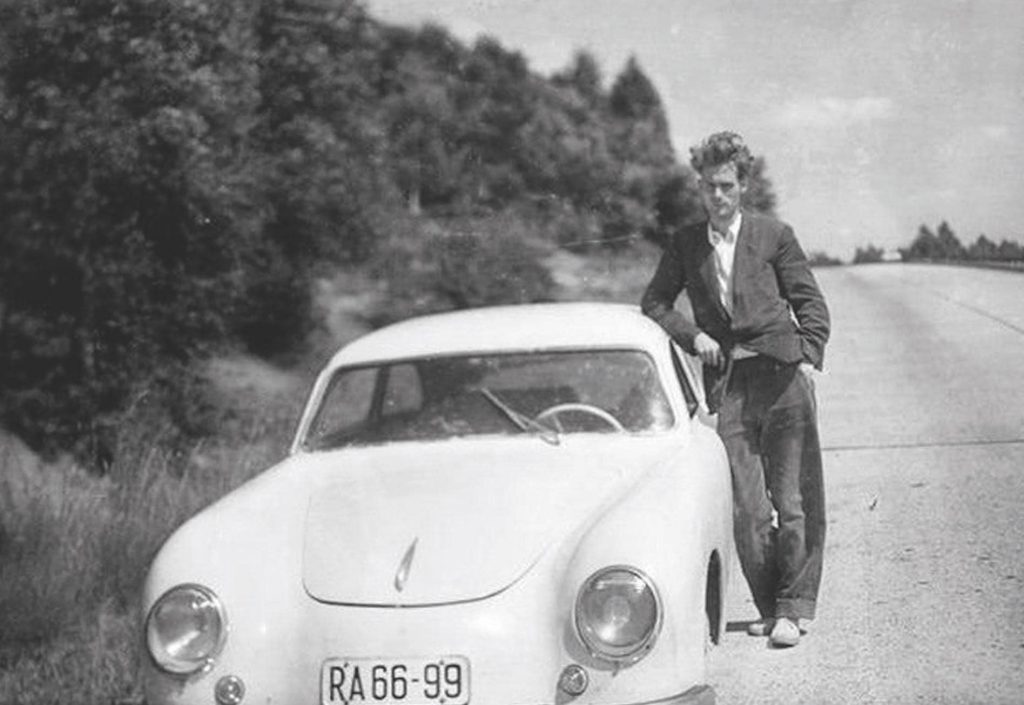

And they used it, first crossing the border into West Germany in 1954, with only a single driver’s license between them and forged West German license plates. Over the next several years, the Reimann brothers proceeded to traipse around Europe, from Switzerland to Italy. This included the trip in 1956 to Stuttgart, where they visited the Porsche factory and left their note for Ferry.

As mentioned, when he issued his reply Ferry Porsche was at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, there to oversee a pair of 550 coupes and a production 356 Carrera, along with a trio of factory-supported privateer cars. Porsche had just handily won that year’s Targa Florio, beating the works entries from Ferrari and Maserati. It is possible his sympathies towards the Reimann brothers stemmed from a shared underdog status, and his recognition that they had created something special despite having desperately limited resources.

Ferry didn’t charge the brothers for the parts he sent – pistons, cylinders, and carburettors – just the shipping costs to the Eduard Winter Porsche dealership in Berlin. As for how to get those parts across the line, that was up to the Reimanns. They charmed their way back into East Germany, rebuilt the car, and suddenly the first Lindner Coupe was capable of a top speed of 80 mph. Not much by modern standards, but that’s quicker than any Trabant ever went.

Further, the Reimanns’ coupe wasn’t the only replica Porsche to come out of the Lindner coachworks. A total of 13 cars were built, though the history of only four has been traced, and there appear to be two survivors. One, commissioned by a shoemaker named Hans Miersch, is shockingly original, as he owned it all the way until 1994. Miersch’s car was built on a Type 82 chassis, but sourcing its steel panels required perhaps even more audacity than the actions of the Reimann brothers. Whereas they only had to smuggle across the Porsche engine components, Miersch had to smuggle in the entire body of his car in steel panels from Czechoslovakia, sweating through multiple trips with the illicit metal concealed in his suitcase.

But where Miersch was able to hang on to his pseudo-Porsche (which he claimed was specially built to accommodate his missing lower leg), even as he lost his shoe factory, the fall of the Iron Curtain ended the travels of the Reimann brothers. They were arrested in 1961 for allegedly planning to escape the DDR, and imprisoned in Berlin’s infamously grim Hohenschönhausen prison. The Porsche replica was seized and presumably scrapped.

Yet the story doesn’t end there. About a decade ago, a Viennese collector named Alexander Fritz came across the badly damaged chassis of what he assumed was a 356. But everything was wrong with it, and it was decayed to the point that some people suggested it was perhaps a Czech-made Tatraplan. Fritz redoubled his research, discovered the Reimann brothers, and reached out to make contact.

The brothers shared their old photos of their youthful roadtrips, and Fritz was hooked. He spent some 7,000 hours bringing his Lindner Coupe (chassis number 4) back from the dead, seven times as long as it took to build the first prototypes. Sadly, Knut Reimann died during the restoration, but Falk lived to see the restoration completed in 2016. He died soon after, but not before knowing that a memory of his youth had been preserved. One that is today recognized by Porsche as a “Genuine Porsche at heart,” even if was not actually made in a Porsche factory.

A great story, I am a long term owner of a 1960 Porshce 356 Cabriolet and can only imagine how difficult it was to make such a car in post war DDR. I wonder how many more interesting stories can be found like this. How people must have struggled.

An inspiring tale of ultimate triumph against deliberate political, economic and social hardship. I wonder if enthusiasts in the UK will be forced to adopt this kind of ingenuity in the coming decades in the face off ever threatening government legislation in its attempt to ultimately ban motoring for all but the wealthy…

I whole-heartedly agree with Nick Hollis’ comment, above.

I am nearing the end of my “stint” so will not see how it goes.

I consider I have been fortunate for my “slot”. The future doesn’t look too bright.

…but a fascinating article for sure. All that hard work under such restricted conditions.

Great Story of how an important work of automotive art can be reincarnated – And Best of all it continues on in the spirit of the Reimann Brothers

Am just finishing up my 356 replica and this article has given me even more inspiration. Thank you!

This is a shining tribute to the tenacity of the Reimann Brothers. They followed their dream star and saw it through to the finish. Well done and well written.