The first time I saw it running was at Goodwood. The smoke-stained, heat-blistered coachwork was battered and torn, and with the Jägermeister-script name emblazoned across the scarlet bonnet, it looked like nothing else at the Festival – it was a monster.

Chief mechanic Gianfranco Dazia attached a tow rope and with Michele Lucente, its sole designated driver at the wheel, the water- and smoke-belching beast was tugged out onto the track. It was some time, however, before the 22-litre, six-cylinder Fiat Bis aero engine gave even the slightest interest in showing a leg. There might have been a small fire, maybe two, then a hollow ‘Boomph! And Mefistofele came to life.

‘CRAKACRAKABLAT! The cacophony was profoundly disturbing, though strangely fitting for a car named after Old Nick himself. In a Goodwood card of race and rally stars, Formula 1 aces and aerobatic displays, Mefistofele drew a crowd like no other.

The second time I saw it was five years later, in 2011, at the old Alfa Romeo test track at Balocco, in Northern Italy. The difference being, I was about to drive it. Mefistofele had been subject to a meticulous rebuild, complete with a new 320bhp A12 engine, which Fiat had ‘found’ under a bench at the stores to its art deco Centro Storica Museum on the appropriately named Corso Dante in Turin.

These units, which once vied with Rolls-Royce as top-notch aviation power, don’t grow on trees, and Dazia was taking good care of it.

“It takes slightly less time to start the Space Shuttle,” he said as he rocked the still running-in engine on its starting handle. Cylinder pressure escaped with a sinister hiss and Dazia stopped after every crank to inspect, rock the tappets by hand, and poke around under the absurdly long bonnets, which when lifted gave the car the appearance of a demonic red raptor.

The silence at the Balocco test track was palpable, every one of us wishing the engine into life if only to vindicate Dazia’s efforts.

A beat for a bit of history here?

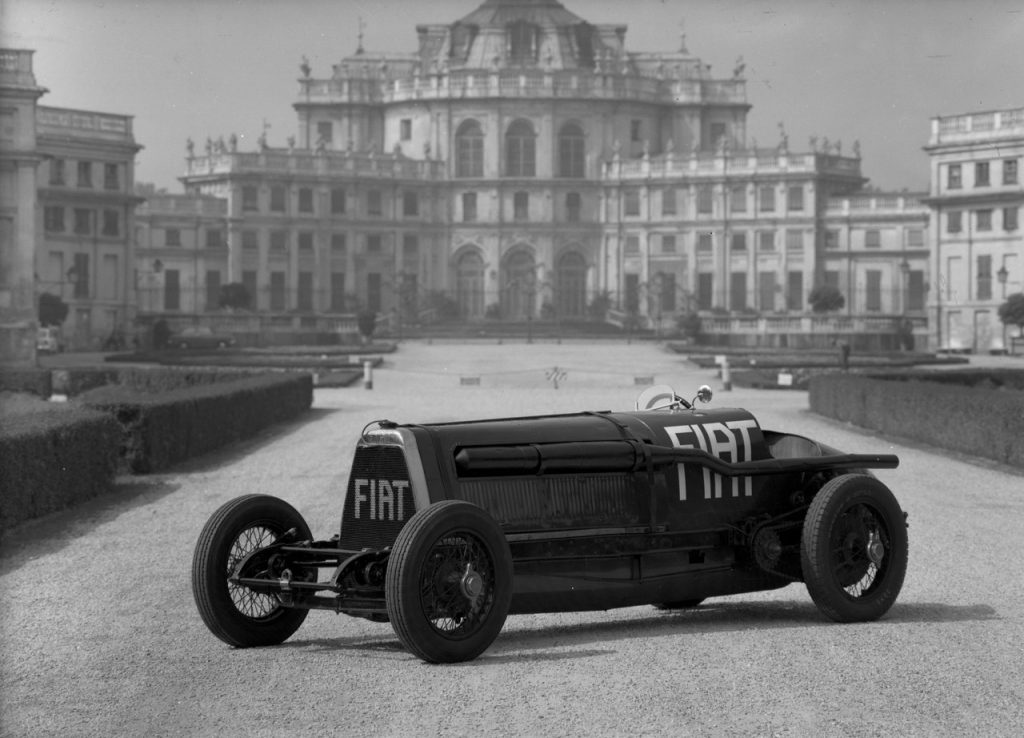

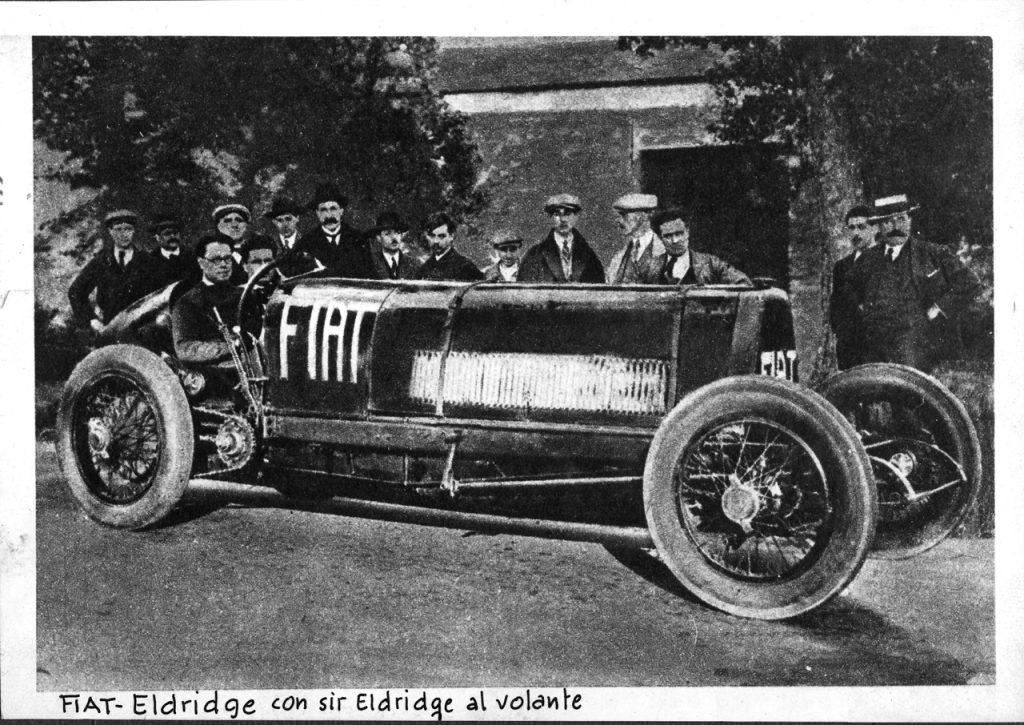

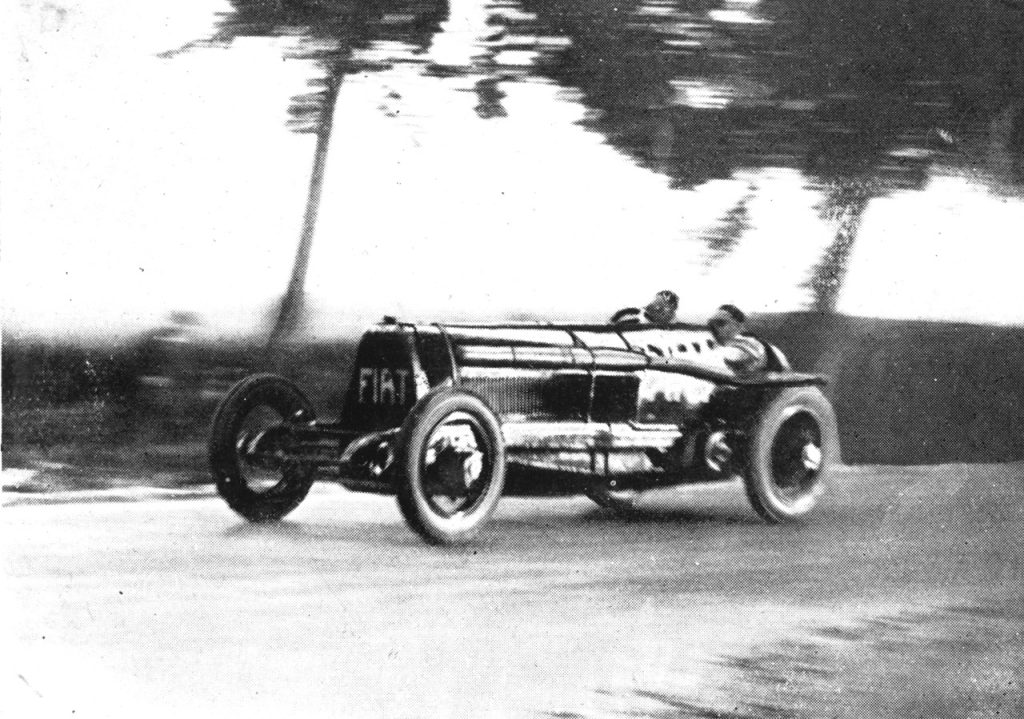

First thing you need to know is that Mefistofele is a genuine record breaker. On 12 July 1924, the bespectacled, tubby old-Harrovian aristocrat, Ernest Eldridge, pointed the bluff nose of his car down the narrow, tree-lined stretch of unpaved Routes d’Orleans at Arpajon, about 18 miles from Paris.

Even a century ago, Mefistofele emitted enough smoke and flame to give a Green Party candidate a fit of the vapours, but undeterred, the brave Eldridge set a new average record of 146.013mph (234.985km/h) over the flying kilometre. It was to be the last time such a record would ever be set on a public road.

Then, in October 1924, Eldridge covered 210.23 kilometres in an hour, which was also claimed as a world record. But the car didn’t come fully assembled as the aero-engined beast that it was and is now.

Eldridge had some previous with these mighty things.

“He was a serious producer of very dangerous automobiles,” comments Maurizio Torchio, the director of Fiat’s Centro Storica.

Eldridge’s previous mount was a 240bhp Maybach aero-engined 1907 Isotta Fraschini chassis stretched to accommodate the 20-litre engine. It won its first race at over 101mph, but dissatisfied, Eldridge then sold it to his friend, Gary ‘Le Champion’ Masurier and downsized to a 10-litre Fiat instead. Having had some success, he then traded it for Mefistofele.

The big Fiat started life as an SB4 race chassis with an 18-litre four-cylinder engine, built by Fiat in 1907 for Sir George Abercromby for the princely sum of £2500. He had specified a car capable of 116mph and capable of winning the Brooklands Montagu Cup. It was delivered in 1908 and with works driver Felice Nazzaro at the wheel it won that year’s Montagu Cup, netting Sir George 250 sovereigns and Nazzaro the unbelievable wage packet at the time of £700.

By 1922, however, after a few seasons of racing, it had fallen on hard times, culminating in one of the biggest blow-ups ever witnessed at Brooklands. At the Whitsun meeting, the rear cylinder block exploded, launching itself skyward through the bonnet, followed by the two rear pistons, which rose like corpses from the grave over the driver and passenger before sinking back into the stricken engine bay.

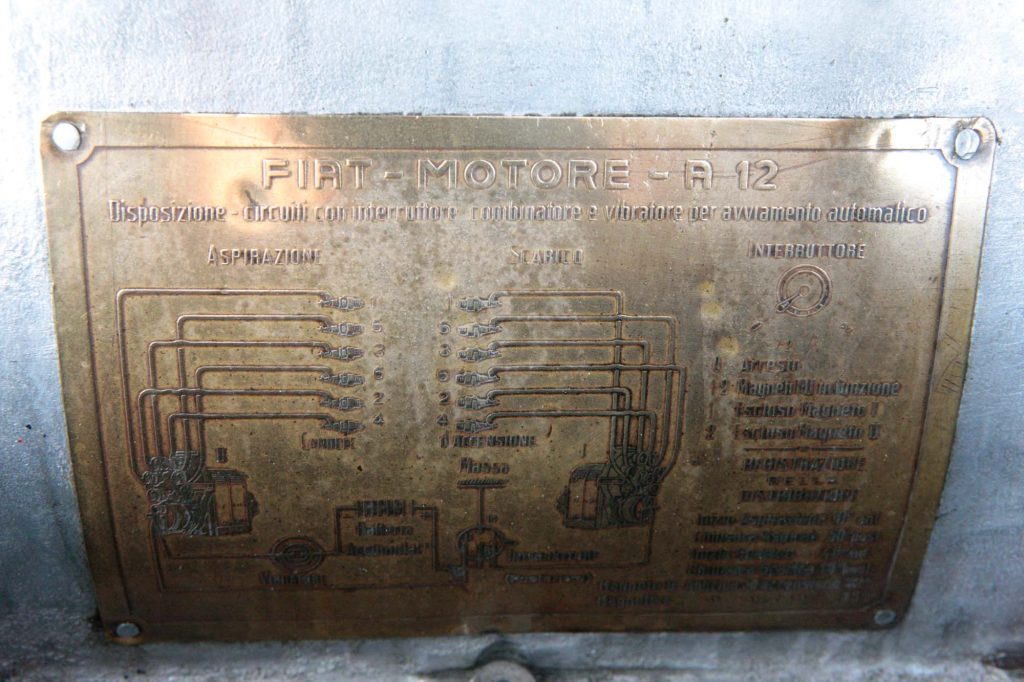

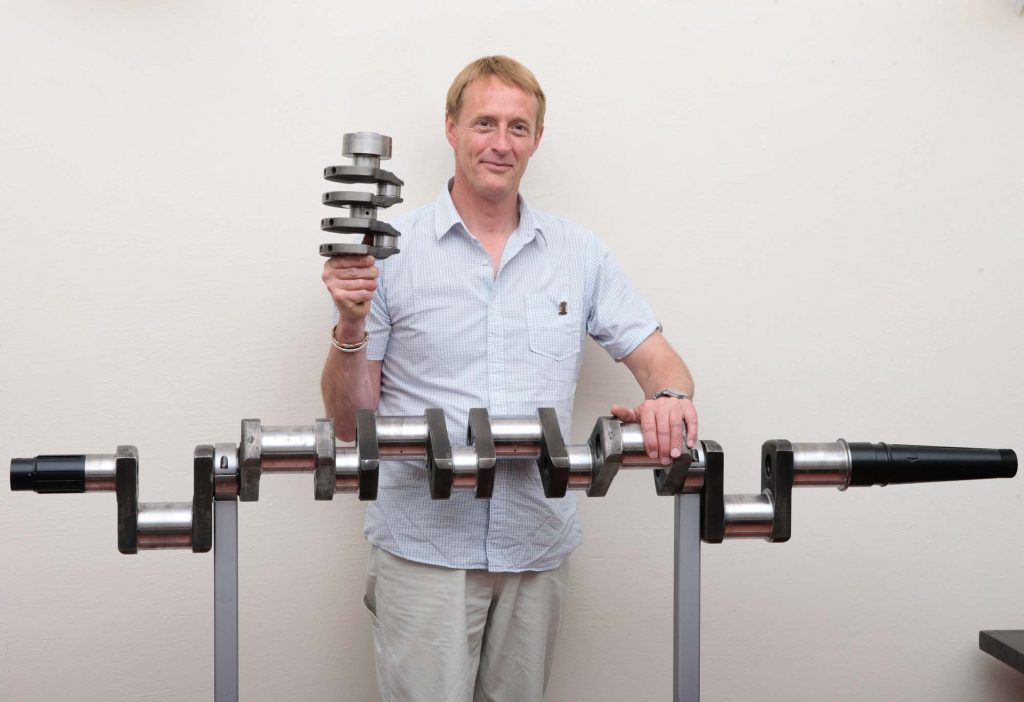

Eldridge bought the scrap for £25 from John Duff and enlisted the services of a Mr Brownridge and Jim Ames (Eldridge’s riding mechanic) to convert the car with a new surplus-stock Fiat aero engine. It started with a 20-inch chassis extension using rails from a London bus. The A12 Bis engine displaces 21,706cc across six cylinders with four plugs and four valves, each driven by an overhead camshaft which braces the top of the engine and is driven off the crank with a bevel gear.

It’s a dry-sump unit with two scavenge pumps, and Eldridge’s team fitted twin carburettors and four magnetos, which helped liberate 320bhp at 1800rpm feeding into a 57-plate clutch pack and a four-speed transmission with no reverse gear. There’s a centre differential driving thick Reynolds chains to each rear wheel.

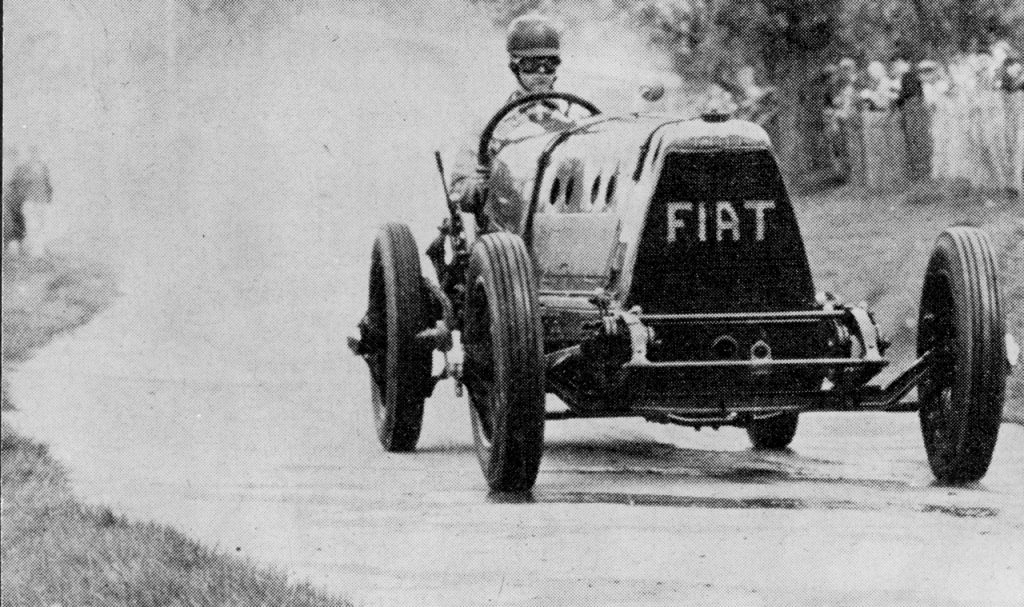

The car had already been christened Mefistofele when it made its re-engined debut at a June 1923 Brooklands summer meeting. It proved a complete handful, breaking its damper mounts and tearing off entire tyre treads.

But drivers back then had the right stuff in spades. Primitive suspension would fire these behemoths into the air like leaping salmon, and contemporary reports of record attempts were epics of lost treads, burst tyres, and scream-in-your-helmet slides. Except they didn’t wear helmets in those days, just woolen jerseys and googles, the latter eschewed by Eldridge, who simply drove in his glasses.

The year after setting the Arpajon speed record, he engaged in a £500-a-side match race against Parry Thomas in his mighty Leyland-Thomas at Brooklands. Described as “devastatingly dangerous” by authoritative journalist Bill Boddy, Eldridge gained an early lead and held Mefistofele in a series of lurid skids on the banking which were so terrifying spectators ran for cover.

Perhaps the dangers persuaded Eldridge to sell Mefistofele on to Masurier, who repainted it green and drove it around on the public roads near Rugby. It then passed through various hands, including those of Peter Wike (who used to drive it to the pub), George Gregson, and Charles and John Naylor, who all drove and raced it hard and well.

At the end of the 1960s, it was purchased by Fiat, but the old engine was well past its best with leaking, corroded water jackets, which defied every attempt to reweld them. Although Fiat produced more than 13,000 of these engines in Turin, these days they are incredibly rare.

Back at Balocco, Mefistofele finally deigned to yield to a push start, and that familiar CRAKACRAKABLAT filled the air as I sat in Eldridge’s chair, bathed in hydrocarbon smoke with snarls of flame emerging from the exhaust.

Unable to sleep the previous night, two quotes rolled like thunder around my brain. The first from Michele Lucente, who has driven this monster at over 100mph. What was it like? I asked.

“I don’t remember,” he confessed. “I am so busy with the steering, the gears, looking for the braking, there’s no time to think about what it is like. When I get out, my hands, they are shaking.”

The other from Jim Ames, Eldridge’s riding mechanic, who recalled the terrifying experience of hanging on, pumping to pressurize the fuel tank, and turning on the oxygen supplement to the intake air all at the same time.

Oh goody!

Heave at the outside lever on the four-speed ‘box. Find a gear, any gear. Nothing doing. I jerk at the lever trying to surprise a gear into engagement. Gnash, grate, clunk, it’s in. The clutch is light, the centre throttle likewise, and we’re off.

Any student of these prewar leviathans will be familiar with the fat, lazy torque of an aero engine. The compression ratio of just 4:1 doesn’t make for the most efficient combustion process. Five huge rings on each piston and big ends the width of my notebook bring levels of internal friction unknown to a modern engineer. If these engines feel a bit lethargic, well, that’s forgivable. Except, this Fiat doesn’t – not in any way. It crackles up and down the huge rev counter like a tiny Alfa Romeo mill. This is a proper Italian sports car engine.

There’s plenty of room round the pedals except to the right, where the transmission brake, throttle, and advance and retard mechanism seem to share the same space and time. You drive with the right side of your foot tilted backwards, and I’m wearing just my socks to get my size 12 in there, which proves painful when everything warms to stove-top temperatures.

I’m so busy concentrating in the first few yards, there is indeed no time to think about what it’s like. On half throttle, the engine shunts back and forth making splendid quantities of smoke. Carbon dioxide emissions are calculated at 3200g/km, but then there’s the unchecked hydrocarbons, carbon monoxides, and oxides of nitrogen, but gasoline has never had a finer pyre.

Finally, I stop fart-arsing around and stand on it. Gadzooks! The needle races round the dial and I’m struggling into second. Again, while most aero-engined monsters gather speed deceptively quickly, Mefistofele slaps you round the chops. It’s fast in a way that modern cars are. Lucente reckons it’s as fast a rally car in the mid-range and I’ve no reason to doubt him.

No discernible brakes of course, and the low-compression engine doesn’t help much in slowing. Nor does the astounding cacophony from the thrashing chains, rattling gears, and banging engine on overrun, which just addles your brain. There’s also the daunting prospect of returning through the smoke screen Mefistofele has just laid down. I hold my breath and turn the wheel. Again, this is a surprise. It’s heavy, but not impossibly so.

Handling is not really an apt description of how Mefistofele attacks corners. Weighing 3500 pounds, she bucks and weaves, the steering juddering as the 21-inch-diameter wheels and tyres strain against their friction dampers, leaf springs, and kingpins. Driving this car in a race must have been a major act of strength and courage.

By the end of about four runs, my hands are shaking so much I have to stop. Dancing with the devil is a serious business and requires a steady hand – and possibly a fortifying glass of grappa afterwards.

Part of my job is trying to make a bit of magic out of cars. It can sometimes be a struggle. Not with Mefistofele, though. I can still hear the crackling engine as I write, feel the sensation of gathering momentum and the exhaust smuts in my ears, the heat on my feet and the bruises on my legs.

You might think such a crowd puller would have been out in force in this, her centenary year. Goodwood possibly, or UTAC, which owns the historic concrete oval track at Montlhéry in France. It lies alongside the Paris-to-Orleans Road, where Eldridge got his record and at which Mefistofele often ran. This year, UTAC is hosting a celebration of the place on October 12 and 13. The group has already requested the appearance of Mefistofele but has been turned down.

Circumstances are keeping the old red record-breaker stuck over her well-filled drip trays in the Centro Storica in Turin. First is the sheer lack of money to tug her around Europe to various events, which costs an inordinate amount. The second is the peculiar role of museums for what are called legacy manufacturers. Stellantis, which owns Fiat, has separate museums for each of its 14 marques, each costing a packet to run and each needing to be profitable – not easy for a museum. The third, which might not be entirely unconnected, is that the Italian government has given the entire Centro Storica Museum national monument status, which means it is protected by law and the upkeep has to be maintained by the owner, i.e. Stellantis. With that process going through at the moment, as Italian author Maurizio Torchio says, “there is a lot of paperwork and sometimes it’s difficult to find the right person to sign it all.”

And in that interim, there Mefistofele sits as her birthday-cake candles flicker and gutter.

What a shame.

Where would we be without British aristocrats?