In Japanese culture, your sixtieth birthday is called kanreki, and it is an anniversary of high significance. In kanji, it is written as two characters: kan for calendar, and reki for return. Kanreki symbolizes not just a milestone, but a time to consider what the future holds, a chance for rebirth. This year, Honda’s great experiment in Formula 1 marks its own kanreki, 60 years at the pinnacle of motorsport. Even now, as the Honda-powered Red Bull R20 has taken Max Verstappen to the brand’s latest championship, Honda must also be wondering what lies ahead.

The first teetering steps of the journey began at the Nürburgring in 1964, for that year’s German Grand Prix. Having qualified last, the spidery little Honda RA271 sat at the back of the grid, nearly a full minute behind pole-sitter John Surtees in his Ferrari 158. Surtees would go on to win the race, the finishing order reading like a list of everyone’s racing heroes: Jim Clark, Dan Gurney, Graham Hill, Bruce McLaren. Way down in thirteenth place, having heroically made up a few places but crashed out after eleven laps, California-born racer Ronnie Bucknum had done the best he could for Honda.

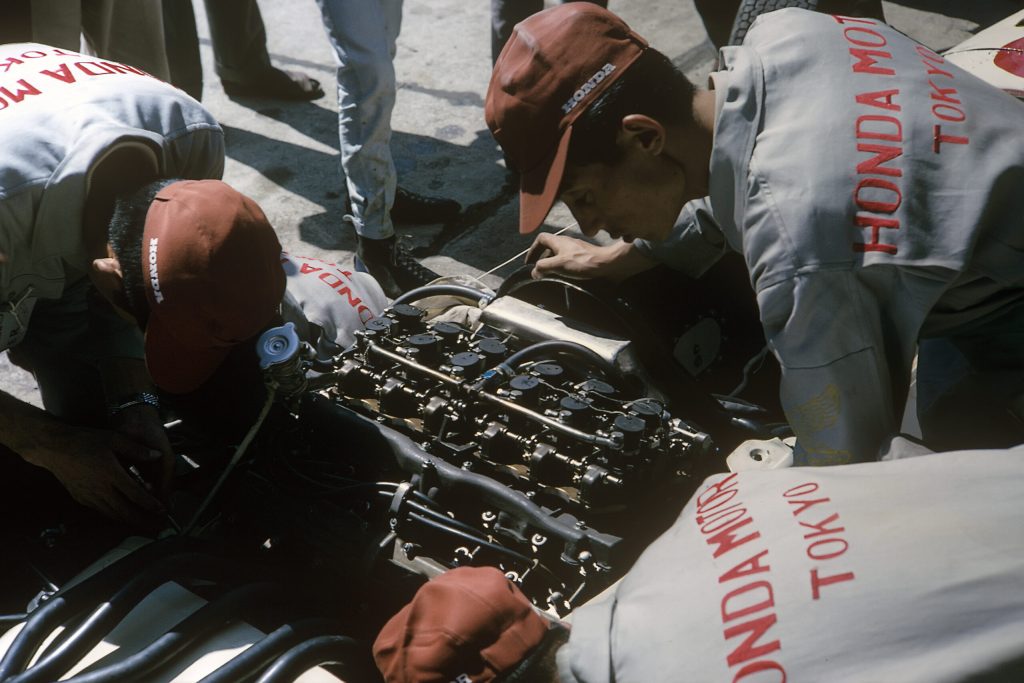

Expectations for Honda among the crowd of journalists covering the race were probably higher than in the team itself. Just a few years prior, Mike Hailwood had ridden the Honda R162 racing motorcycle to the 250cc World Championship. On paper, the RA271’s 1495cc V12 was infused with the world’s largest motorcycle manufacturer’s know-how, revving to 13,000rpm and developing 200bhp. It was the only V12 in a field of V8s. In reality, the engine misfired and overheated and was generally cantankerous. Yet Honda perservered.

To add a little more context, it’s worth looking at what Honda’s road car ambitions were at the time. In 1964, the ubiquitous Civic was still six years away. Honda made the adorable but functional T360 kei truck and the S600 sports car. Win or lose at F1, it was still just a motorcycle company.

However, if you were paying attention, there were hints at future greatness. In attendance at that Nürburgring debut was Japanese motoring journalist Shotaro Kobayashi, the founder of Car Graphic, one of the leading automotive magazines across the Pacific. Kobayashi had shipped his own personal S600 to Europe and had spent the weeks leading up to the race visiting the Porsche factory, meeting with Colin Chapman, and driving the Furka Pass. His little Honda sports car went the distance, and he knew Honda’s F1 team would too.

At the head of the team was Yoshio Nakamura, an aeronautical engineer who had joined Honda in 1958. He had worked on the company’s fledgling kei car development, and had even driven the prototype RA270 racer during testing in Japan. He was fluent in English, and was a natural lead for the F1 team.

The RA271’s modest first outing is usually the only thing the history books mention, skipping straight on to the more successful RA272. However, the first car did properly give the Honda team hope. After missing the Austrian Grand Prix to work on developing the car, Honda showed up at the Italian Grand Prix at Monza, in Ferrari’s back yard. This time, Bucknum qualified in the top ten, the Honda’s V12 hitting peak revs on the straight and running strong.

In the race itself, the RA271 distinguished itself in a fashion that would later be considered atypical for Honda: raw power on the straights, tricky handling in the corners. Bucknum powered his way up to third place, proving that Honda’s V12 had the juice to run with the established front-runners, a Japanese twelve-cylinder howling its heart out in front of the red-clad tifosi. However, when the dust settled, the RA271 finished thirteenth again, although this time it had at least gone the full distance.

the RA271 would compete just one more time, at the US Grand Prix at Watkins Glen. Here it again ran just outside the top ten, retiring after a blown head gasket after 50-plus laps. The standings showed that Honda’s maiden year in F1 hadn’t produced much. However, the bones of greatness were in there. And furthermore, Soichiro Honda was not a throw-in-the-towel kinda guy.

The next year, Honda was back with the RA272, an evolution of the original 1.5-litre machine. The FIA had announced that 1965 would be the last time this classification would be used, so the RA272 was basically just a polished-up RA271. As is so often the case when a car is optimised rather than completely redesigned, the recipe worked.

First off, and not that this counts in competition, it was beautiful. The RA271 has some awkward angles, a cross between a soap box derby racer and a cigar, but the RA272 is stunning in its delicacy, a V12-powered Star Wars pod racer. Also, that beauty was functional: The shape was more aerodynamic, and it offered better cooling. The V12 now made between 230 and 240bhp, and it could be reliably revved to a maximum of 14,000rpm. All these improvements and the Honda team also managed to find a way to excise 27 kilos out of the kerb weight.

Honda also hired Californian Paul Richard Ginther, better known as Richie, to partner Bucknum. Born in Hollywood and raised in Santa Monica, Ginther was an interesting fellow. He came into the racing world as a skilled mechanic, having trained as an aircraft mechanic and formed a friendship with the great Phil Hill, F1 champion and the first driver to complete the Triple Crown of endurance racing (Daytona, Sebring, Le Mans). Ginther proved to be an adept racer in his own right, and the Honda team figured his mechanical skills would help in shaking down the RA272 to be as quick and reliable as possible.

The debut at Monaco was nothing special, the rev-happy Hondas being unsuited to the course. Honda had brought three cars for its two drivers, but both drivers ended up failing to finish, retiring with transmission problems.

At the next race, however, Ginther’s RA272 scored Honda its first points in F1 racing. After qualifying fourth, the actual race was all about the wet-weather dominance of Jim Clark and Jackie Stewart, the pair of race leaders lapping the entire field. Even so, Ginther was able to hold the Honda to a solid mid-field performance, with the other RA272 of Bucknum breaking down mid-race.

For the rest of the season, Honda stayed mid-pack. Ginther repeatedly did well in qualifying, but never managed to finish better than sixth. By the time of the last event on the calendar, the Mexican Grand Prix, Honda was in the points but only as an also-ran.

In Mexico, however, the old racing adage proved true: To finish first, you must first finish. Ginther managed to qualify his RA272 third on the grid, alongside the Brabham of Dan Gurney and the Lotus of Jim Clark. When the green flag waved, the Honda shot forward and passed them, and Ginther never looked back. Clark’s Lotus retired with engine problems, but the RA272 ran faithful and true, leading all 65 laps.

It was a historic moment. Within one year of entering F1, and within just two years of starting to build road cars, Honda was Asia’s first F1 winning manufacturer. Nakamura sent home a Caesar’s message to Japan: “Veni, vidi, vici.”

In this first era of racing, Honda would compete for three more years, notching one more victory with F1 champion John Surtees at the wheel of a car co-developed with British racing specialist Lola. Here, Honda found the formula it would apply to all its F1 endeavours going forward: It would supply the engine rather than develop the car from the chassis up.

Perhaps no more perfect example of this recipe exists than the McLaren MP4/6 driven by Ayrton Senna to the 1991 F1 world championship. As the only V12-powered F1 racing machine to win a Formula 1 championship, and the last with a manual transmission to do so, it is a fitting heir to the RA272’s first win for Honda. It, too, is a thing of beauty.

For the 2026 F1 season, Honda has partnered with the Aston Martin Aramco F1 team. With engineering impresario Adrian Newey joining the team, things could be very interesting in a couple of years.

At 60, Honda’s F1 efforts are again pushing forward into uncharted territories. F1’s new regulations require a balance between internal combustion and electric power, and the ability to run on carbon-neutral fuels. For the engineers who will set to work on this new powertrain, there are all kinds of problems to sort out. Even after 60 years, there is no time to rest on past laurels. Keeping up with the future requires constant rebirth.

Honda’s contributions to racing have been exemplary. Even Ferrari never attempted motorcycles.