“Is there a better £15,000 sports saloon?” asked the headline on the cover of Autocar & Motor, in April 1991. Somewhat spoiling the surprise, before readers had had a chance to pick a copy off the newsstand and flick to the road test of the new BMW 318i, the editor answered the question: “We don’t think so.”

Launched in November 1990, the E36 was the successor to the popular E30, the entry-level model that saw BMW’s reach spread far and wide across the world’s middle classes.

It was a big deal. At the time, the 3 Series accounted for half of BMW’s total production. The company wanted its baby to continue growing up, with an expanded range, more mature engineering, improved safety and – shrewdly – a step up the ladder of middle-class aspiration.

A handful of months after the third-generation 3 Series was revealed to press and public alike, across the world the verdicts began flowing in. Car magazine pitched the 325i against five contenders and it comfortably outclassed the lot. After its first steer of 320i and 325i versions, Performance Car couldn’t see room for improvement: “The car is genuinely hard to criticise.” Autocar praised its “deep-seated excellence.” Across the pond, Road & Track declared it a “sweetheart.” Looking back at reviews from the period, it is clear nobody had a bad word to say about it.

My abiding memory is of the first group test, with a 320i, and finding that BMW had left the competition standing. It made the Mercedes 190E feel like a saloon designed by old men for old men. Rover’s 400 couldn’t compete for desirability. Alfa’s ageing 75 was great to drive but crap in almost every other respect. The Audi 80 was lumpen, the Honda Accord as hum-drum as a pair of Marks and Sparks grey flannel trousers.

The Choice for the Man From M

None of this comes as any surprise to Dirk Häcker. The 62-year-old family man is a resident of Augsburg, about 70 clicks to the west of Munich, and in his garage you’ll find an E36 325i. The significance? Häcker is vice president of engineering for BMW M – in other words, he’s the person in charge of developing new M models – and began his career with BMW in 1988, working on the creation of, you guessed it, the E36.

As a mechanical engineer, his specialism was developing traction control and brake control systems for BMW, more specifically for the successor to the E30 3 Series. What he and his colleagues created was a Continental-based system known as ASC+T – automatic stability (slip) control and traction. Initially an option on certain models, this early system used the ABS (antilock braking) system to apply the rear wheel brakes to prevent wheelspin, and was complemented by management of engine torque delivery to the back wheels, by either controlling the throttle valve, retarding ignition timing, or shutting down fuel injection.

For Häcker and his colleagues, it was an exciting new world where performance and safety intersected to make BMW’s cars more capable in all conditions. Those early steps made it possible for the likes of BMW to sell bread-and-butter M cars with nigh-on 550 horsepower going through the rear wheels.

How ironic, then, that Häcker’s own 325i doesn’t have those same systems he helped develop. His car is a manual 325i saloon, with the optional factory-fitted limited-slip differential and M Technic suspension setup, so it sits a little lower on 17-inch alloy wheels, and he is only the second owner – after BMW.

“I bought in in 1993, and it’s a model-year ’92 that was an ex-BMW car. I liked it because I worked on the E36 during its development, and from the beginning, I was very happy with the performance and dynamic characteristics of the car – also the speed of the car, in comparison with the E30.”

Evolving in a Computer-Aided Era

Häcker had come from an E30 325i convertible and found much to like about its successor.

It brought computer-aided design to the road. Production of the bodyshell employed entirely robotised welding, which allowed for a 25 per cent reduction in the number of spot welds. Yet BMW’s engineers were able to reduce flexural distortion (bending of the bodyshell) by 30 per cent and torsional distortion (twisting forces) by 60 per cent, while weight distribution hit the magic 50:50 ratio. The latter was helped by mounting the engines as far back toward the bulkhead as possible and placing the battery in the boot.

Beneath that boot floor, the rear suspension system was an adaptation of that which had proved itself in the niche but critically acclaimed Z1 roadster. The outgoing E30 had a reputation for becoming somewhat trouser-soiling at the limit of adhesion, especially on wet bends whether under power or when decelerating, so time and money were invested in adapting the Z1’s so-called Z-axle, a multilink independent affair that offered vastly improved control of geometry changes.

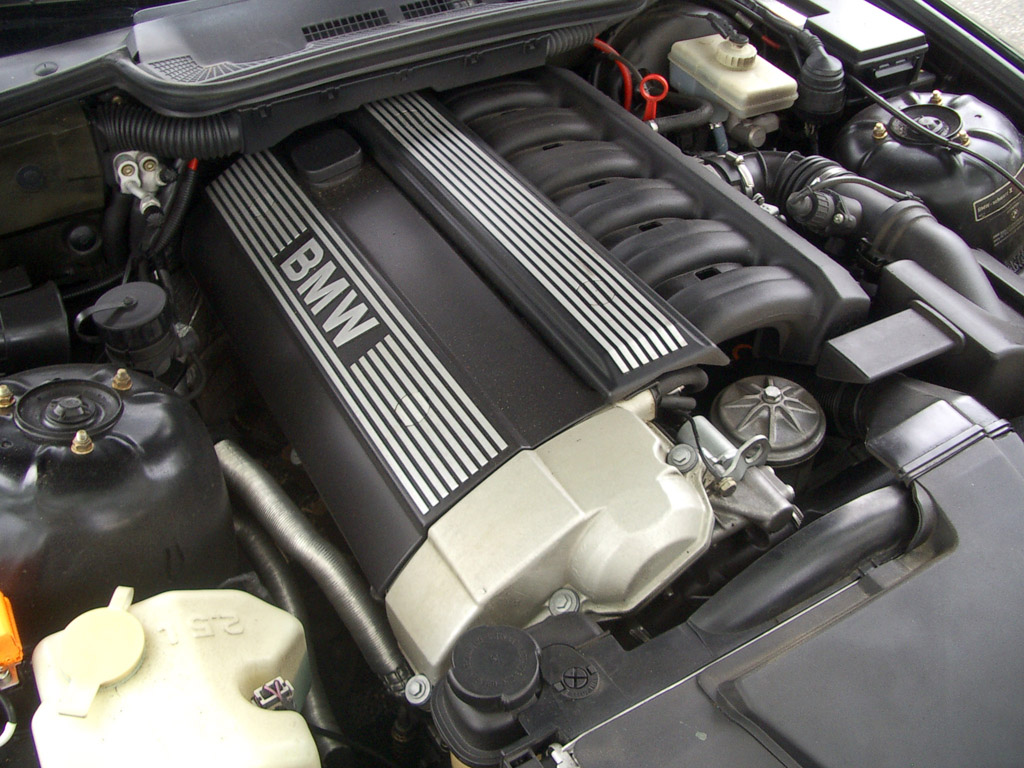

Under the bonnet, advances included four-valves per cylinder, overhead cams, advanced Bosch electronics, and onboard microprocessors to manage both performance and emissions in the new age of the catalytic converter and unleaded fuel. There was a new five-speed manual gearbox and an optional new five-speed automatic from ZF. And haters of diesel engines were finally silenced by the comparatively silken 2.5-litre straight-six turbo that powered the 325td from 1991.

However, the highlight of the engine range was never in doubt: the 325i. Its 2494cc straight-six M50 motor delivered 189bhp at 5900rpm and 177Ibft at 4700rpm, enough in the 1295kg model to see the manual version claim a 0–60mph acceleration time of 7.9 seconds and a top speed of 145mph. Impressive enough, but it was the effortless power delivery, uncanny throttle response, and harmonious acoustics that sent a tingle down the driver’s spine.

Many would argue that the straight-six engine is intrinsically part of the identity of a BMW sports saloon. Is that a view shared by Häcker? “I think the six-cylinder is a very big step for BMW. Obviously, the four-cylinder and V8 have been, depending on the era, important. But the inline-six is the most significant because it has featured through so many decades.”

That lineage can be traced back to the 303 of 1933, followed by the successful and acclaimed 328 roadster. More than anything, says Häcker, it’s the feeling of the E36 being perfectly calibrated for its time and the resources and know-how BMW had at its disposal that makes it such a high point and benchmark for today’s engineers.

With that in mind, after driving modern M cars, what is it about getting back into his E36 325i that Häcker so enjoys? “It’s a different sort of fun. There’s a feeling of emotion that comes with it, because it’s older. And although it’s not the same performance like modern M cars, it’s very pure, it’s very manual, and very focused with a lot of good feedback. I think it’s a very typical representation of the BMW feeling in those years, the Nineties.” Little wonder that he has clocked up about 120,000km to date in it.

Häcker is, of course, right in saying if you cut the car open, it would bleed BMW. To this day, despite having a longer wheelbase than the E30, the E36 feels like a compact car (in part helped by the driver-centric, snug cockpit) and is a joy to throw around – for the simple fact it is so much more sure-footed and better tied down when you extend it over a good stretch of road. A fact helped in no small part by rack-and-pinion steering that (with the exception of the 316i) was far faster-acting than in the old E30, with 3.4 turns lock to lock.

Smooth Operator: Designing the E36 3 Series

That modern, computer-age engineering extended far beyond the mechanical ingredients. The E36’s body was every inch the product of CAD and exhaustive work in the wind-tunnel. At the time, its appearance was acclaimed by all; not one reviewer had a bad word to say about the way the third-generation 3 Series looked.

That’s thanks to Pinky Lai, the Royal College of Art–trained designer whose proposal was overseen by Claus Luthe and picked by the board to progress to production. Its details and proportions would come to define BMWs of the modern era.

It was also better than its predecessor at tackling every car’s adversary: the air. It was more aerodynamic than the E30, which shouldn’t have come as a surprise given that car’s design was ageing, eight years on from its launch. By fairing in the round headlights, angling the bonded front and rear windscreens to 61 and 66 degrees, respectively, and decluttering the body, engineers recorded a drag figure of 0.29Cd for the skinny-tyred 316i. At the same time, front and rear lift were cut by 44 and 19 per cent, respectively.

Much was made of the body’s use of recycled, and indeed recyclable, materials. But you can bet that wasn’t the reason Porsche courted Lai after learning of the hotshot at BMW. The E36 went on to transform BMW’s image, attracting upwardly mobile younger drivers who would remain loyal to the brand, working their way through the range over time. Porsche needed someone with that far-reaching vision to help it achieve much the same for the 911.

Buyers could ultimately choose from five different body styles – saloon, coupé, Touring estate, convertible, and the hatchback Compact – and there was a wide choice of engines. The coupé, launched in 1991 (the same year as the convertible), was a first for the range. It may not have looked all that different to the saloon but almost every body panel was different, from the bonnet to roof, while frameless windows gave it an elegant feel. BMW referred to it initially as a two-door, but there was no question this was a coupé pitched squarely at cars like the Honda Prelude, Rover 200 coupé, Vauxhall Calibra, and Volkswagen Corrado, and it brought with it genuine four-seat practicality that saw sales surge.

The hatchback Compact, meanwhile, was introduced in 1994 to chip away at Volkswagen’s success with the Golf. Some were critical of the parts-bin approach and work-experience body design, but it proved a money-spinner for the brand. It took until 1995 for the family-friendly Touring version to join the lineup.

But things weren’t all plain sailing for the E36. When the flagship M3 arrived on the scene in 1992, the searing 3-litre, 286bhp M Power six came in for praise. But the chassis was let down by slow-geared steering that featured a variable assistance system.

I remember spending more hours than strictly necessary with colleagues tackling skid-pads and test tracks with the first Dakar Yellow test cars, struggling to get a feel for the balance of the grippy chassis and the moment the rear tyres decided to let go of the road surface. It was a hard car to read – a criticism BMW addressed with the 3.2-litre, six-speed M3 Evolution, and absolutely nailed with the subsequent E46 M3.

Keeping It in the Family

Which meant that, when all was said and done, the 325i really was the sweet spot in the E36 range. It was deeply captivating for a family car, sensual yet sensible, one that you’d increasingly enjoy as the miles and months of ownership passed.

Or, in Häcker’s case, the decades. His two children grew up with the 325i in the family. “The car was six years old when my son was born, so it could be an idea to keep it for all time,” suggests Häcker. They haven’t yet driven it, but he’d be happy for them to have a go.

When he has time, Häcker will perform basic maintenance himself, leaving the servicing to a local BMW workshop “so that I get the full service book stamps!” The most recent job he tackled was inspecting the body and getting under the car to look for signs of rust, then cleaning and treating any affected areas so that it will be fit for many more decades of duty for the Häcker family.

That kind of longevity, both in the way the E36 325i has gracefully aged and in the way it continues to treat those who care for one, surely makes it a modern-classic worth hunting down. But don’t take my word for it – ask Herr Häcker.

I suggest someone at Jaguar reads and digests this success story…