In 1969, with the mid-range GS nearly ready for production, Citroën began looking at ways to replace the DS. This was a monumentally difficult task for an ambitious company that had more ideas than money. The new car, named CX to highlight its aerodynamic lines, was shaped by a clashing blend of buyer expectations, technological limitations, and geopolitical factors. Dotted by setbacks and U-turns, the winding path to production finally ended when the CX made its debut in August 1974.

Although it had been updated in 1967, the DS entered production in 1955, so its successor couldn’t settle for evolutionary styling. It needed to look all-new. Led by Robert Opron, who was also responsible for the SM, the members of the design team let their imaginations run wild. Some of the early sketches showed a strikingly wedge-shaped one-box saloon that resembled a flattened modern-day minivan.

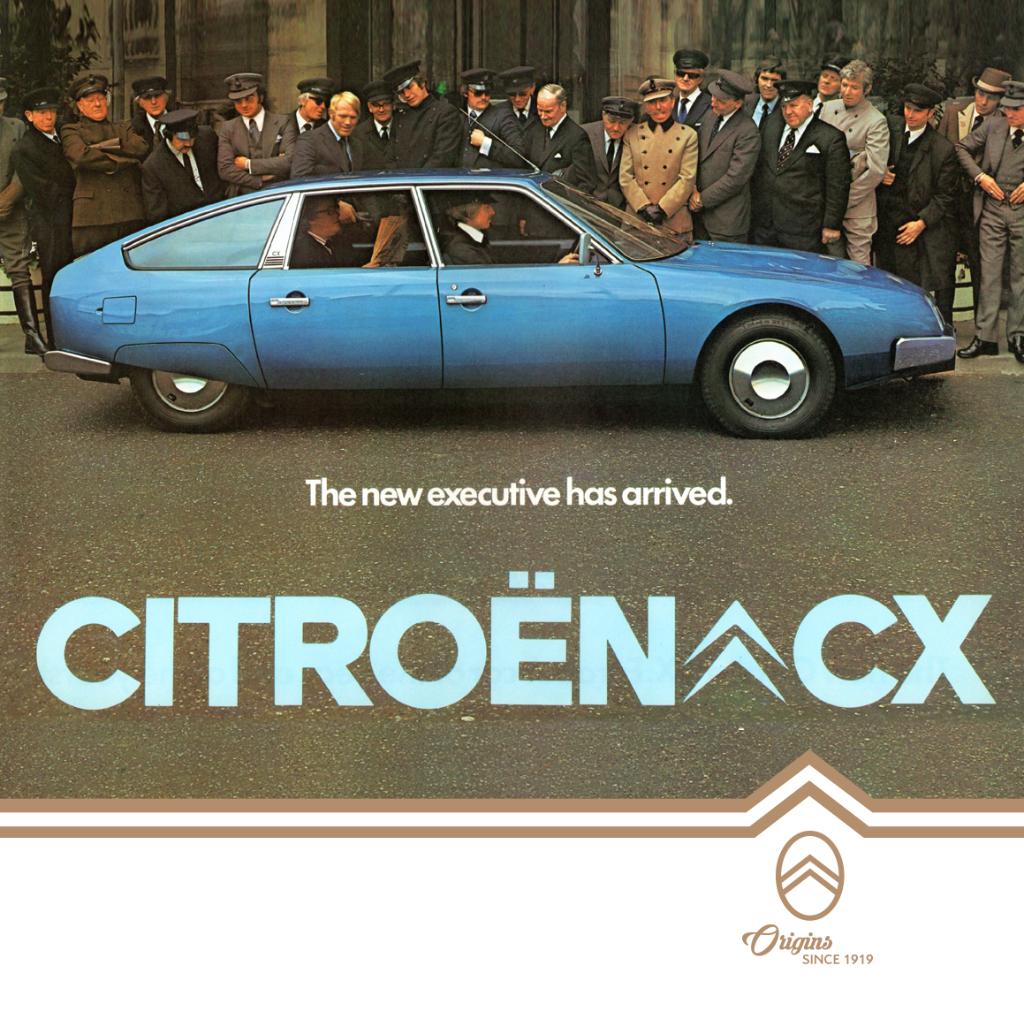

The one-box silhouette was quickly detoured, and the CX – called Project L internally during the development process – gradually morphed into what buyers would later recognise as the logical successor to the DS. It wasn’t a copy of its predecessor, but it remained identifiable as a flagship Citroën saloon thanks to an elongated silhouette and covered rear wheel arches. One of its most unusual styling cues was the concave rear window, which was an alternative to a rear wiper. The directional headlights added to the DS in 1967 were not fitted to the CX for cost reasons, however.

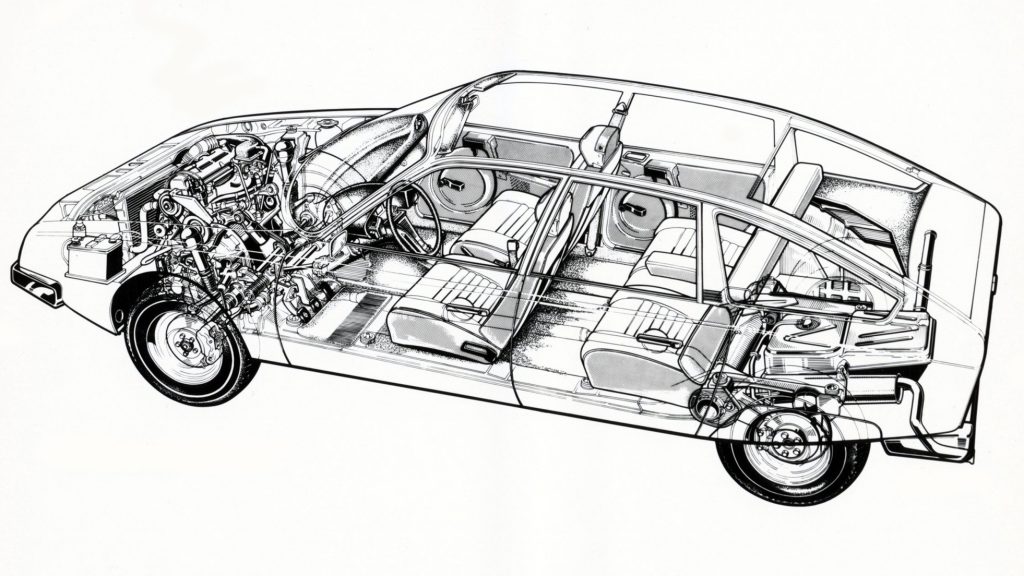

Citroën nonetheless wanted to market the CX as a highly futuristic car. Using an evolution of the hydropneumatic suspension system was a given, and the brand also planned to apply the lessons learnt from years of testing Wankel engines to its upcoming flagship. The range-topping CX was supposed to get a three-rotor, 1.5-litre rotary rated at about 160 horsepower, and the line-up should have also included a mid-range model with a two-rotor, 900cc engine tuned to develop about 110 horsepower. Familiar DS-sourced four-cylinder engines would have powered the entry-level variants.

Quick, luxurious, and comfortable – on paper, the CX sounded like Citroën’s S-Class. Several problems appeared as the project neared completion, however, and the Wankel was canned at the last minute.

One major setback was beyond the brand’s control: timing. The plan to release a big saloon with a fuel-thirsty Wankel engine sounded ridiculous in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis. Another major setback likely could have been predicted, however: reliability. Citroën developed rotary engines via a joint-venture called Comotor that it operated with NSU. The tie-up also spawned the twin-rotor Wankel found in the Ro80, and this engine was far from trouble-free. The CX probably would have inherited many of the same problems, including the rotor seal failure sometimes attributed to over-revving.

Added together, these issues promised to make the new Citroën flagship immune to commercial success – the short-lived GS Birotor had proven this point very well and cost the brand a fortune. Trying to salvage the engine by putting it in a helicopter was a brave but ultimately senseless project.

Canning the Wankel-powered trims put Citroën in a bad position. Strapped for cash, it was left with a flagship saloon approaching its 20th birthday and a new flagship saloon without an engine. Developing a new engine was ruled out due to cost- and timing-related concerns, and using the SM’s Maserati-designed 90-degree V6 wasn’t possible. Prototypes were allegedly built, but they were too tight of a fit.

Instead of going back to the drawing board, Citroën went back to its parts bin. The CX made its debut in August 1974 with a 2.0-litre four-cylinder rated at 102 horsepower. The more expensive CX 2200 went on sale the following year and benefited from a 112-horsepower, 2.2-litre four. Both engines were carried over from the DS, though several small changes were made for the CX. Front-wheel-drive and a four-speed manual transmission initially came standard regardless of displacement.

Even without a Wankel or a V6, the CX received a warm reception from the public and the press. It scored a landslide victory in the 1975 European Car of the Year competition, finishing far ahead of the original Volkswagen Golf, which took second place, and the Audi 50, which finished third. Citroën quickly expanded the range with a diesel-burning variant called the CX 2200 D and a long-wheelbase version named the CX 2400 Prestige, which featured a living room–like interior. Sometimes referred to as a limousine, the Prestige proved particularly popular among members of the French government.

The longest evolution of the CX was largely aimed at families and antiques dealers. Released in early 1976, the CX estate stretched nearly 194 inches long (about an inch longer than the Prestige and more than 10 inches longer than the standard-wheelbase model) and gained a higher roof panel to free up a cavernous amount of trunk space. The clever hydropneumatic suspension system kept the rear end level regardless of how many kids, suitcases, or late-16th-century buffets it was loaded with.

Like the DS, the CX received several visual and technical updates during its long career. The range notably grew toward the top with the performance-focused, 128-horsepower GTI released in 1977, and the 168-horsepower GTI Turbo launched for 1985, with a top speed of nearly 140mph. The first major visual change also came in 1985, when Citroën gave the saloon and estate variants of the CX a revised design characterised by body-coloured plastic bumpers and a more modern-looking interior.

About 150,000 units of the CX were built in 1978, the model’s best year in terms of sales, and the millionth example was made in October 1987. By that point, Citroën had already started working on a successor to the model, which was called XM (yep, just like the BMW) and shared several parts with the Peugeot 605. The company built about a dozen CX-based prototypes named REGAMO to test the new, more advanced Hydractive suspension system it planned to inaugurate with the XM.

While the CX saloon quietly retired in 1989 to make room for the XM, the estate received the Evasion nameplate and carried on until 1991, when the XM spawned its own long-roof model. CX production totalled 1,041,560 saloons and 128,185 estates. It was outsold by its predecessor, which became an unfortunate trend for Citroën: XM production ended in 2000 after around 334,000 units were built.

The vast majority of CXs built were sold in Europe. Citroën withdrew from the American market the same year the CX made its debut, and its presence on other continents, such as Asia, was tiny at best.

With a handful of notable exceptions, such as low-mileage, high-spec examples, the CX was largely snubbed by collectors until relatively recently. Enthusiasts began turning their attention to the model after DS prices left the stratosphere, but while the CX has become relatively sought after, it remains reasonably attainable in Europe – especially in France. Projects and parts cars cost less than £2000, running well-kept examples trade hands for under £5000, and impeccably original or fully restored cars can be found for under £15,000.