Retard the ignition, a smidge of hand throttle, and a thumbs up to engineer Dietmar Krieger. He braces and swings the starter for this supercharged four-cylinder race car and it explodes into stentorian cacophony. The single oval exhaust under my elbow jets out against the concrete walls of the Sindelfingen Mercedes test track in Germany and straight back into my ears. Really should have worn those defenders…

I grip the big wooden wheel and press the leather cone clutch, wait a couple of seconds for things to calm in the four-speed crash ’box and push the soup-ladle–sized lever down by my right leg into first with a tiny graunch. Lift to the engagement point, press the centre throttle and then straight up with the clutch. With a jerk and a growl, we’re off. You don’t slip cone clutches and my riding mechanic, museum engineer Manfred Oechsle, nods his approval.

Second gear almost immediately, then double declutch into third with just a bit of rattle from the gears and smoothly into fourth; now we’re travelling and the square-set bonnet lifts like the snout of a hunting hound at the sound of the horn. This is where it wants to be, on a race track, giving its all, but it’s been a long time since it was last caparisoned for battle—100 years in fact.

So many ways into this story: the winner that wasn’t; the red paint matched from a black-and-white photo; the power of research; the benefits of never throwing anything away; the perils of looking too closely…

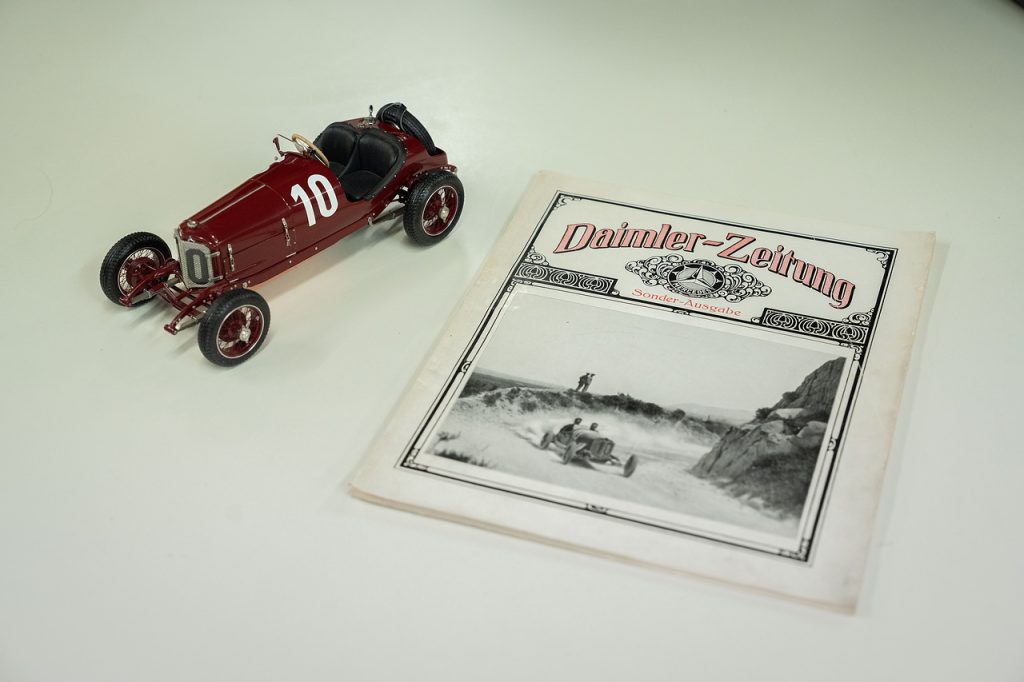

For 20 years, this car, an ex-works Mercedes (not Benz, though, as it was built just before the merger of the two companies) was displayed on a piece of fake concrete banking in the legendary Mercedes Benz museum. The display card said this battered old warrior was the winner of the 1924 Targa Florio, driven by Christian Werner, the first non-Italian to win the Sicilian classic. None of it quite true…

To begin at the beginning, Werner’s “winner” was part of a team of five cars all driven down from Germany to Italy and across on the ferry to Sicily for this important race. Mercedes had won in 1922, but in 1924, the team was determined to consolidate its success. The 2-litre supercharged cars were fast, with fine handling and narrow bodies to suit Sicily’s narrow roads. The works team consisted of Werner in car no. 10, Christian Lautenschlager in car 32, and Alfred Neubauer—who went on to become the feted Mercedes-Benz racing team manager—in car 23. The fourth car was a spare used for training and reconnaissance, and there was a 1914 Grand Prix car there for show.

The Targa Florio was created in 1906 by industrialist and auto enthusiast Vincenzo Florio, who had also created the Coppa Florio in Brescia. As an impresario he didn’t muck about, employing local artists to create driver’s medals and publishing a magazine, Rapiditas, which promoted the race and its entrants.

The original course length was 92 miles on treacherous mountain roads, with over 3600 feet of elevation change and more than 2000 corners per lap, many of them hazardous hairpins with sharp drops. The weather could be highly changeable, the roads were unsealed, and the cars would slide around and create columns of dust. In those beast-like cars, drivers needed pluck and skill, and the first-ever race was won by Alessandro Cagno, an experienced racing driver in an Itala.

By the mid 1920s, the course had been changed in length, but if anything the event had gained in popularity. This was a time when the motor industry was still in its infancy. Big-ticket races were scarce. The 24 Hours of Le Mans was only inaugurated in 1923 and the Italian Mille Miglia was started in 1927. Grand Prix racing was nothing like the current Formula 1 championship, and hill climbs and speed trials were equally as important. Yet the public had an insatiable appetite for the spectacle of these early automobilistes, wrestling their huge, unwieldy, aero-engined brutes.

By 1924, the Targa Florio was actually two races: the 268-mile Targa Florio, comprised of four laps of the bumpy, 67-mile course; and the Coppa Florio, a 336-mile race that was simply five laps of the same course.

Werner’s was the first victory by a non-Italian since 1920, and he led race from the start against fierce opposition from Giulio Masetti’s Alfa Romeo. He set the fastest laps in both races, and if you add in the Coppa Termini, the prize Mercedes claimed as the best team, then 1924 was a clean sweep for the Stuttgart firm. The extensive Mercedes archive reveals old files with the original gushing press reports of victory, as they praised the team’s practice strategy, running the length of the course several times and honing its pit work with well-drilled tire changes and refueling, which had reduced each pit stop to under three minutes.

And it mattered. At this time, private car sales volumes were exploding and the

development of reliable, high-speed engines and electrics in racing really did improve the breed—and also sold cars.

What better automobile would there be to celebrate a century of Mercedes’ racing prowess than this red winner? So, in 2022, it was taken off its banking and rolled into the museum workshops.

And why was it painted red? The international convention of the times was that German cars were white, British cars green, Italian cars red, and French cars blue. On the Targa Florio, however, there were tales of skullduggery, with partisan locals throwing rocks and other hazards in front of non-Italian, non-red entries. Red paint was Mercedes’ way of trying to confuse the issue; from a distance, its cars would look like Italian entries.

“It’s not a disadvantage in an Italian street race to have your car painted red,” says Marcus Breitschwerdt, the boss of the museum. And you can see how last-minute this decision was, from the fact that in the original pictures, Werner’s car used mudguards borrowed from another car with the underside left in the traditional Mercedes white.

Despite the importance of the victory, Werner’s “winning” car didn’t stay long in the works. In 1925, it was sold to privateer Wilhelm Eberhardt. It was entered for various races, but Eberhardt so loved driving it on the road that he had the narrow body widened to better accommodate his wife as a passenger and fitted a full windscreen and lights. Thus modified, it was repurchased by the factory in 1937, displayed in various museums, and then moved to the factory museum in Untertürkheim in 1961.

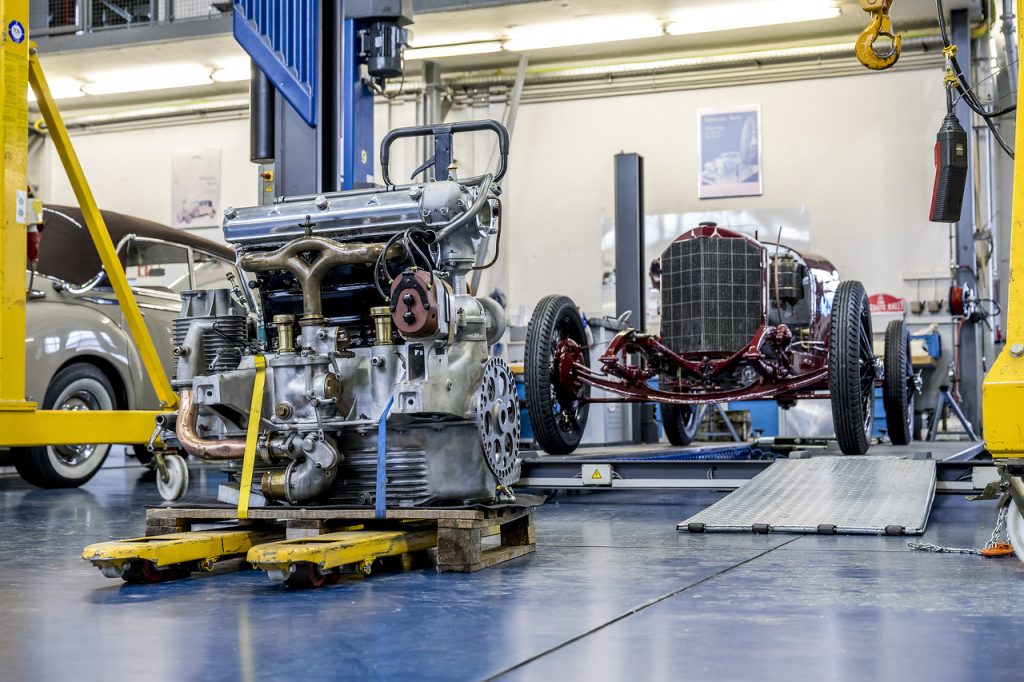

Two years ago, once it had been moved into the museum workshops, the research began in earnest and it soon became clear that what was hoped to be just a “freshen up” would in fact be an extensive rebuild, as the car hadn’t run for many years. The archive also revealed a surprising and not entirely welcome discovery…

Poring through the records it became clear that this wasn’t Werner’s winning car; it was the tenth-placed Lautenschlager car, number 32. The fate of Werner’s car is still unclear, but the archive revealed photographs of it smashed almost beyond recognition, so it seems likely it was scrapped. Was Eberhardt sold a ringer? No one seems to know.

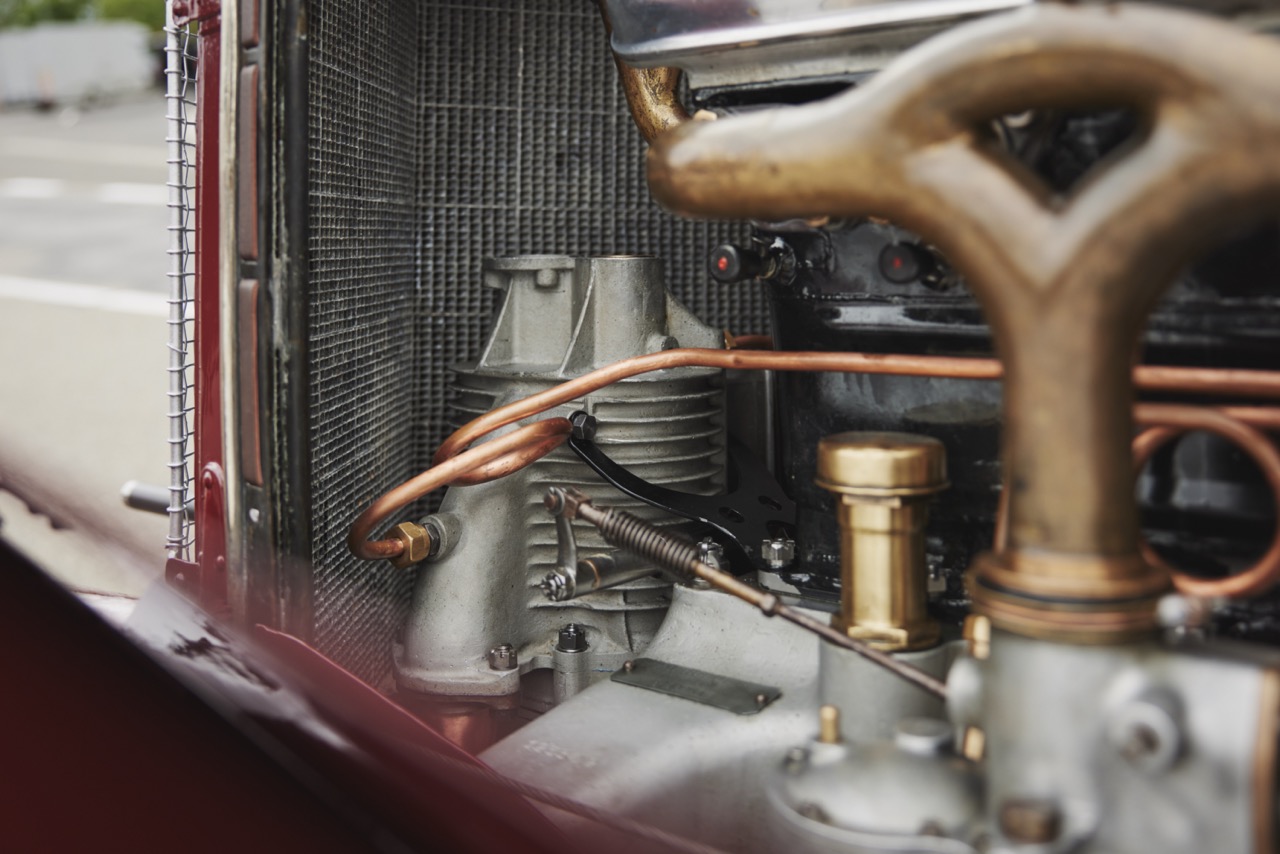

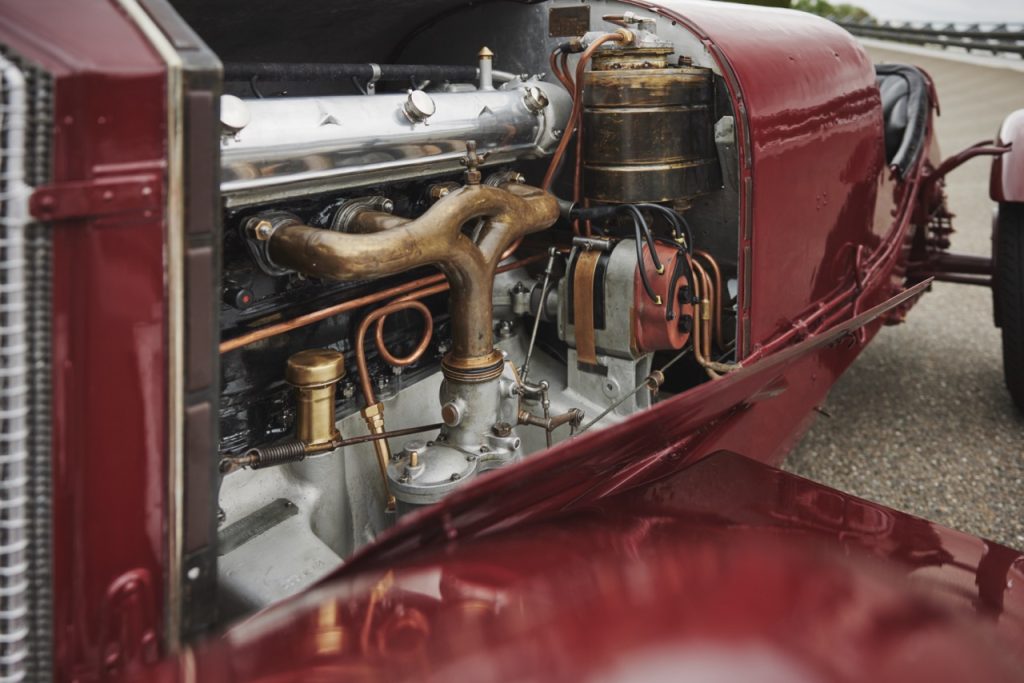

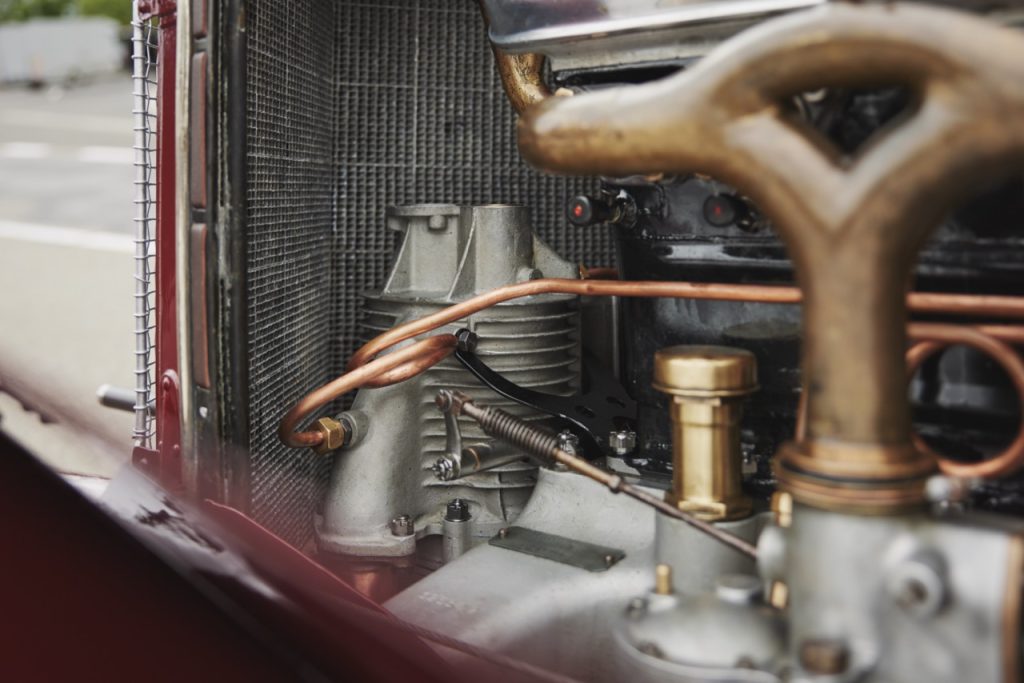

Notwithstanding its marginally less glorious history, the museum decided to continue with the restoration of the Lautenschlager car. The body and drivetrain were removed from the frame and the body was placed in a full-length hot box to re-anneal the metal so it could be worked on without it cracking. The drivetrain was carefully stripped and the archive found the original engineering drawings and contemporary reports.

“We never throw anything away,” says Breitschwerdt.

Repainting the car posed its own set of problems. For a start, the paint was a turpentine-oil–based coach enamel hardly used these days. The second issue was that, although the car was still red, it had been repainted at some point long ago. That paint had weathered over the years, and all the original photographs were in black and white. What, exactly, was the original’s proper shade?

Experts were hired from the art conservation departments of local universities and paint samples carefully examined and analysed. “We looked in places where the painters don’t like to sand,” says Volker Lück, a master furniture restorer who was charged with hand-painting the little racer with original-style paint of the correct hue.

Trouble was, the turpentine-based paint had to be mixed by hand with the pigment, then applied and laid off with a brush, and there were 10 layers, each taking a couple of days to dry.

“Of course, on the days I did the job, there were squadrons of suicidal flies,” says Lück, “but in the archive there were stories of Mercedes having the same problems.”

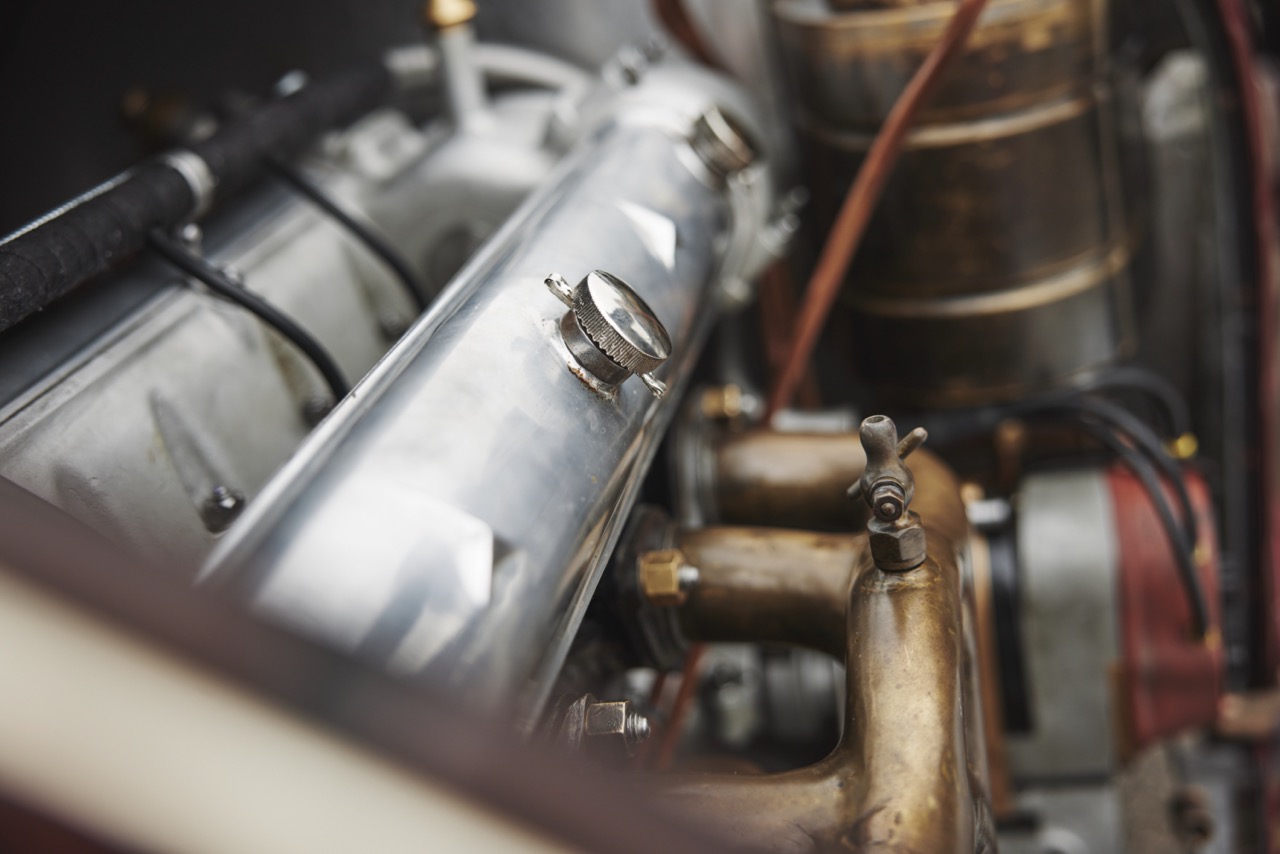

The engine had been designed by Paul Daimler, known as the “the king of kompressors” and his replacement, Ferdinand Porsche, who had joined Daimler in April 1923. This two-litre, twin-camshaft four-cylinder was lighter than the six-cylinder equivalent and with forced induction, it produced a healthy 125bhp. The clutch-actuated Roots-type blower merely needed a refresh, as did the roller-bearing crank, but one of the cylinder liners was damaged, the water jackets were badly corroded, and the camshafts had to be metal sprayed and ground back to original spec, together with new pistons and bearings and much hard work.

“We had to do a lot,” says Krieger, a museum engineer. “It was a sobering experience.”

That was my first introduction to the car, stripped and battered, with much still to do, and with a clock ticking, for a serious program of appearances had been planned for the old racer in its centenary year.

There were several false starts, but I finally got to meet the car for a drive at Sindelfingen on 8 May. It felt like an appointment with destiny, no public relations fanfare, no pomp and circumstance, just this red car and a team of engineers from the museum. Truth be told, I felt as if I were Werner testing the machine for the first time over 100 years ago.

A mizzle sweeps across the track and through the circular pits. The Mercedes looks millimetre perfect, with proportions straight out of a child’s picture book. Spattered with droplets of water, the claret-red coachwork undulates gently, showing every brush stroke and blow and scrape of the old charger’s life.

“No build-and-block and no filler,” says Gert van der Meij of Dutch specialists MCW, which has done a fair bit of the heavy lifting in this restoration. They retained as much of the original car as possible.

The museum engineers greet me like an old friend as I pull on overalls and a flying helmet. They’ve warmed the engine but it’s so cold they’ve had to blanket half the radiator to keep the heat in.

A century on, it feels every inch a Mercedes works racer, from the reverence the mechanics show it to the obvious care and love that has gone into its restoration and conservation, without overdoing it. This was, after all, a race car.

Frames back then were smaller, and they have to take the entire seat padding out to accommodate my generous six-foot build. I’m sitting on bolt heads in a bare aluminium seat shell. Apparently, former F1 ace Karl Wendlinger had to do the same, so I’m in good company.

First job is to get the photographs, and while it’s geared down for the tight Sicilian corners, the old Mercedes hates the speed-restricted running, pulling and hunting at the leash anxiously to escape the attentions of Max Balazs’ Nikon.

Then we’re on our own, Oechsle and I, a whole test track to ourselves. The old car exits one of the banked turns and as I enter the straight, it’s now or never…

“What amazes me is how responsive this car is,” Oechsle yells in my ear as I open her up on the long straight. He’s so right, this little Mercedes feels every inch a thoroughbred as it tears up the concrete, the engine rasping, the car vibrating and twisting, almost alive in my hands.

It feels far from vintage—anything but a hundred years old—as I push the brakes into the banking and the nose dives toward the apex. There’s progression and precision here, with little lost movement, and the wheel can be minutely adjusted with none of the see-sawing required of some of its contemporaries. On the wide track it feels tiny, but as I push the throttle again for the next straight, it’s so eager, every inch the racer as it noisily dashes between the curves. Back on the race circuit after so many dormant years.

“You won’t leave it to rot again, will you?” I ask Oechsle as we go for a cheeky next lap (it’s that sort of car). He shakes his head. Not at all.

You’ll see this amazing survivor, the winner that wasn’t, at this year’s Goodwood Festival of Speed and then again at Pebble Beach. It was also in Italy mid-May for the Emilia-Romagna Grand Prix at Imola, where Mercedes-Benz F1 driver George Russell took the wheel.

As I write, thinking back to the drive, Oechsle is right. The little car belies its 100 years and feels really quite modern in the way it drives. I hope he’s right and Mercedes does keep this Targa Florio racer in good running condition, if only to remind us where we’ve come from and the peaks of what we’ve attained.