Whether it’s the rotund eldritch horror from the 19th century or today’s more cheerful grinning character, Bibendum, more commonly known as the Michelin Man, is one of the world’s oldest and most recognisable mascots.

Ostensibly a clever way of flogging round, rubber hoops for your chosen method of transport, he’s become the face of one of the world’s largest tyre manufacturers, a familiar figure in motorsport, and even a figurehead for cuisine, thanks to the respected Michelin Guide and the stars it awards to restaurants around the world.

Who is Bibendum?

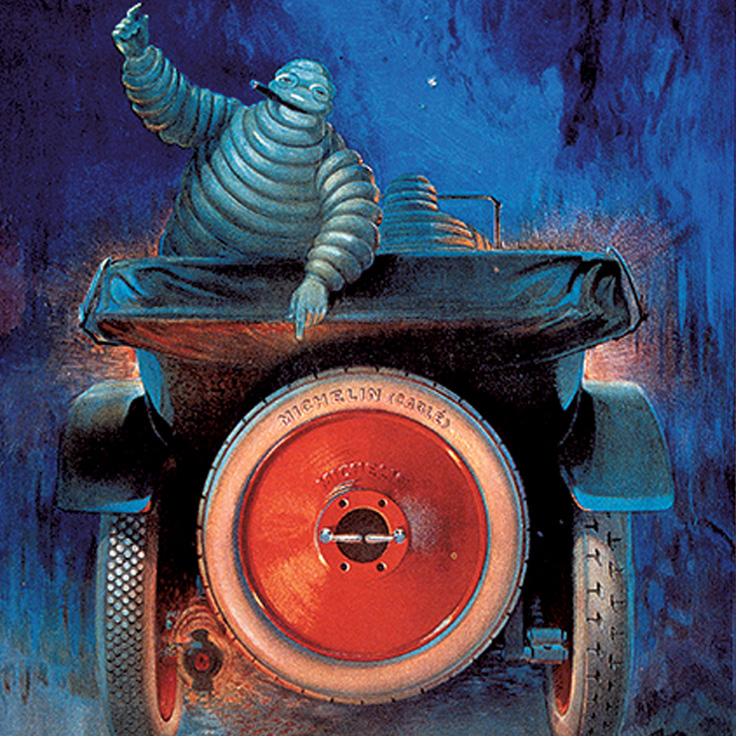

He is, if you hadn’t guessed, a man made of tyres, though he started as merely a stack, when during 1894’s Exposition internationale et coloniale in Lyon, Édouard and André Michelin spotted an armless figure in the form of the pile of tyres advertising their wares.

The stack’s transformation into a character came four years later, when André asked cartoonist Marius Rossillon to adapt an earlier cartoon of a large, drinking individual, with a figure made from tyres. His white colour, a characteristic continued to this day, reflects the colour of natural rubber used in tyres at the time, before carbon was added as a strengthener.

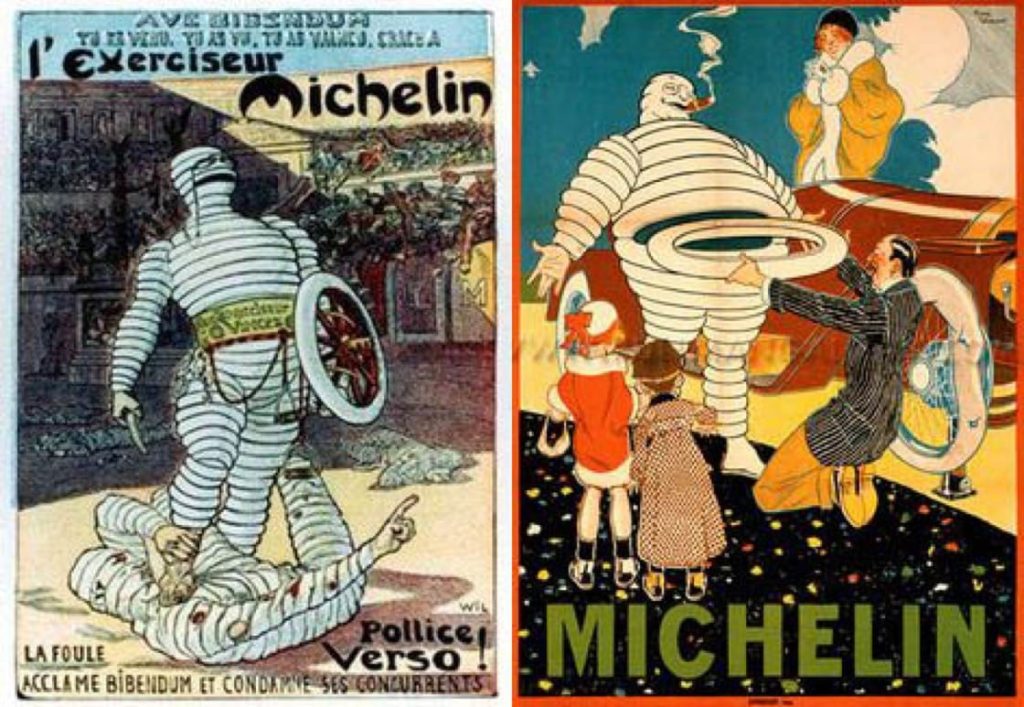

The accompanying slogan, “Nunc est Bibendum” (“now we must drink”, taken from the odes of Roman poet Horace) perhaps made more sense when the character was human, but Rossillon had an answer for that. His poster, used largely unchanged from 1898 well into the 1910s, cleverly depicted the character holding aloft a glass full of nails and other detritus, alongside deflated competitor characters, suggesting Michelin’s tyres “drink obstacles”.

By the early 20th century Michelin was already producing guidebooks promoting travel (and indirectly, but certainly intentionally, its tyres) across France, and it’s here that the name Bibendum stuck for the company’s portly mascot. Michelin hired writer Maurice Edmond Sailland, also known as Curnonsky, to pen the company’s gastronomy columns for newspaper Le Journal. Curnonsky began signing off the columns as “Bibendum” from 1908 – so it’s likely the character was officially named around this time.

A man made of tyres

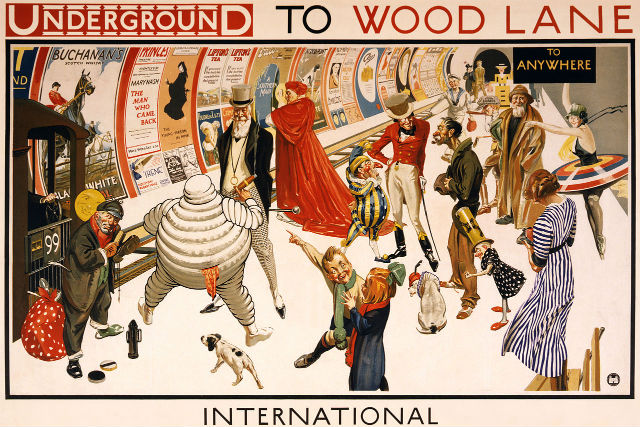

Disconcertingly, it was many years before Bibendum gained anything you might call a face, the character frequently pictured drinking or smoking through a terrifyingly dark gap in his head, and wearing fashionable “pince-nez” spectacles despite lacking a nez to pince. Or indeed, distinct eyes. The somewhat high-society settings in which he was often depicted were very deliberate though, appealing directly to the well-to-do motoring classes of the era.

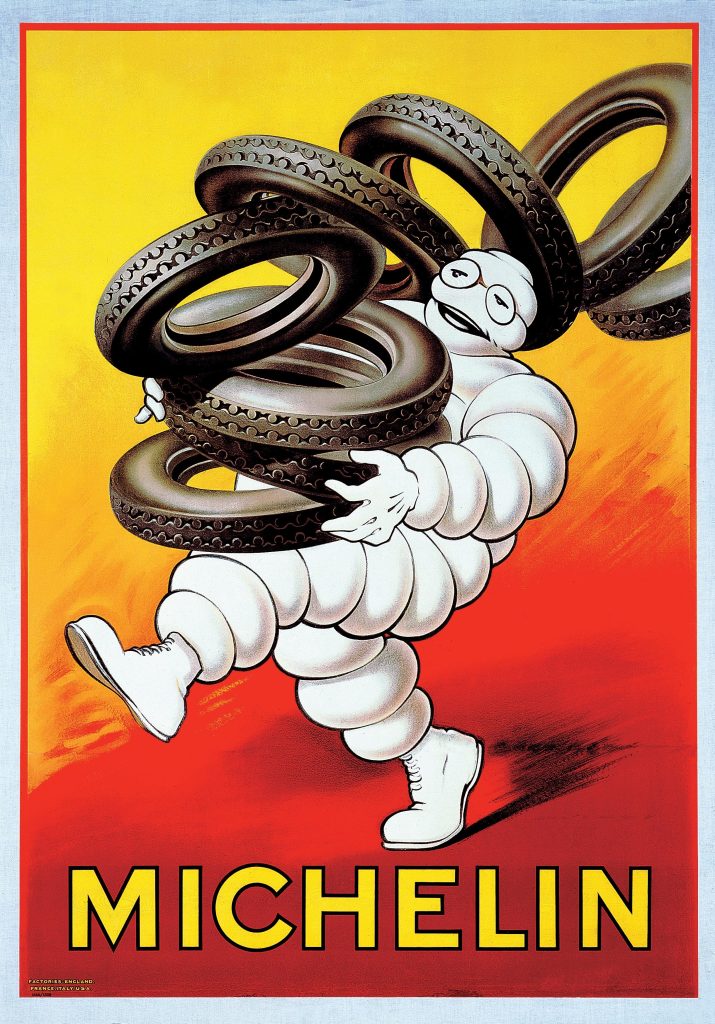

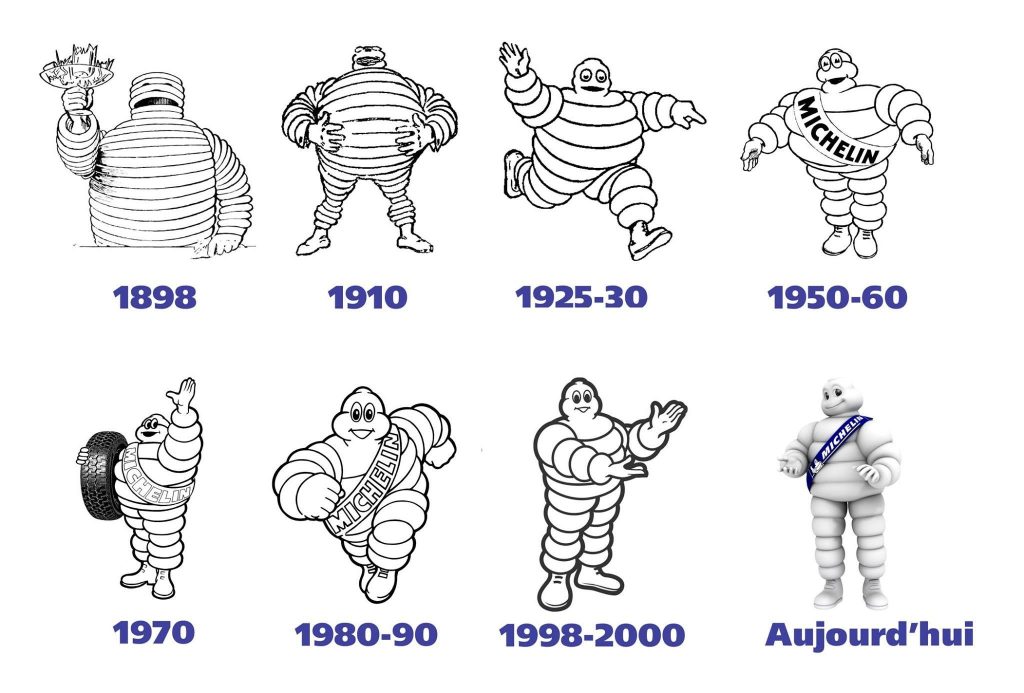

As car buyers changed, so too did Bibendum’s image. In 1925 the character gained a proper face – if you can call it that – with eyes and a distinct mouth, and only the suggestion that his head was made from tyres. Rather than drinking or smoking, he was often depicted rolling a tyre down the road, or riding a bicycle (imagine the squeaking).

The famous pageant-style sash appeared in 1950, and through the 1970s and 1980s Bibendum became both more cheery and human in his appearance, and also more athletic – between 1980 and 1990, the character was more often than not depicted sprinting towards the viewer, perhaps a nod to the company’s increasing involvement in motor sport. Today, one might call him chubby rather than corpulent.

Restaurants and reviews

If you wish to emulate his physique, that’s been possible since 1987 in the restaurant at Michelin House in Chelsea.

The art-deco building was opened as Michelin’s UK headquarters in 1911, but became a mixed-use venue in the 1930s when the company moved to Stoke-on-Trent. The company returned after WWII, still as owners of the premises, but finally sold the building in 1985.

The buyers, Sir Terence Conran and publisher Paul Hamlyn, redeveloped Michelin House into a mixed-use commercial development, including a restaurant and oyster bar, today run by chef Claude Bosi.

The building was listed in 1969, and is best-known for its spectacular stained-glass window depicting the original, drinking Bibendum. The windows were removed and sent to Stoke during the Second World War to prevent damage, but this backfired somewhat when the originals could not be found again after the war. The windows seen today are instead close replicas, installed in the late 1940s, based on old photographs, and to this day, the originals are still missing.

The mystery hasn’t affected Claude Bosi’s restaurant though, which enjoys a two Michelin star rating. Stars have become almost as significant a part of Michelin’s heritage as tyres, and the rating system was conceived in 1926 to score restaurants featured in the popular Michelin Guides.

One, two, or three stars can be awarded, and in 1936, Michelin revealed its criteria for each: One star for “a very good restaurant in its category”, two for “excellent cooking, worth a detour”, and three for “exceptional cuisine, worth a special journey”.

It has become a gold standard for the industry, if one that’s easy to criticise for its focus on high-end eating; don’t expect any stars even at the world’s greatest greasy caff or waffle bar. Oh, and for the fact that France has the most starred eateries, with 628 in total – read into that what you will – ahead of Japan’s 414. Great Britain and Ireland? 194 at time of writing, from 1284 restaurants listed in the guide.

Star ratings are awarded by anonymous reviewers; a great shame, given that we probably won’t get to see Bibendum lounging in the corner of a restaurant eyeing the presentation of an eight-course meal like that old Not The Nine O’Clock News sketch. But if you do, make sure to raise a glass of nails in his honour.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage for daily news, features, interviews and buying guides, or better still, bookmark it. Or sign up for stories straight to your inbox, and subscribe to our newsletter.