This story was originally published by Hagerty US.

On April 22, 1941, the Luftwaffe was waging war on the British naval base at Devonport. The signal tower atop Mount Wise glowed red in warning as the Heinkels and Junkers unloaded tons of explosive ordinance. Civilians huddled in brick bomb shelters. Searchlights and anti-aircraft guns lit up the sky. In the blackout gloom below, dotted with fires and explosions, a single headlight cut through the darkness. Onward the rider came through the rubble-strewn streets, her message bag slung at her side, her hand twisting the throttle open.

We do not know what message Women’s Royal Naval Service Third Officer Pamela McGeorge carried, only that she rode through hell and flame like a woman possessed. A bomb fell close, the blast knocking her from her bike, sprawling and sliding. She picked herself up, ran back – the motorcycle was a tangle of bent metal. She hefted her bag, turned, and ran the rest of the way to deliver the message.

For her bravery, for her service, and perhaps for her insistence on immediately going out again as a dispatch rider, Officer McGeorge was awarded the British Empire Medal. While her actions were heroic, they were not unique. In fact, by 1940, all of the British Navy’s dispatch riders were women. It was a dangerous job, delivering intelligence and orders from headquarters to military bases all over the UK. Over the course of the war, more than a hundred of these women would be killed serving their country.

Originally, the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) was formed in 1917, during WWI. The Navy was the first of Britain’s armed forces to actively recruit women, and the Wrens, as they became known, were telegraph operators, clerks, and code experts. The director of the Wrens was the highly capable Dame Katharine Furst, who was later both an expert skier and head of the World Association of Girl Guides and Scouts.

It’s worth noting that Wren McGeorge had been a Sea Ranger, the Naval equivalent of a Guide. There was a great deal of overlap between the Guiding movement and the various WWII women’s auxiliaries. Girls who had grown up learning to be skilled and independent were not about to sit at home while a war was on.

Dame Vera Matthews, who led the Wrens from 1939–46, had previously volunteered as a Wren herself on the very day the WRNS was created in 1917. Matthews was highly educated, well-travelled, and a shrewd judge of character. A natural leader, she would preside over a force of nearly 75,000 women: radar operators, administrative staff, pilots, anti-aircraft crew – and dispatch riders.

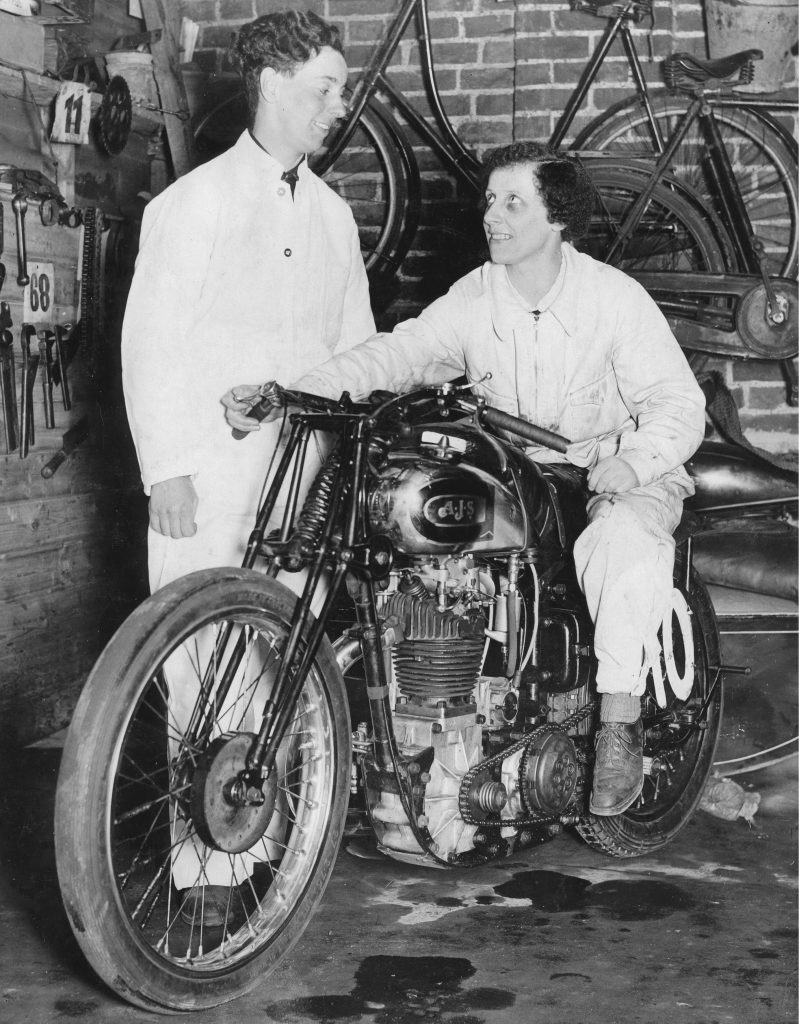

The WRNS organisation was fortunate at first in having a small pool of experienced women motorcyclists to draw on. During the prewar period, society on the whole didn’t exactly encourage women to take up motorsport, but more than a few did anyway.

Pioneering female British motorcycle racers like Florence Blenkiron, Theresa Wallach, and Beatrice Shilling led the way for many women riders. All three rode their bikes to more than 100 mph at the bumpy Brooklands circuit. Wallach and Blenkiron did a highly-publicised motorcycle ride from London all the way to Cape Town, South Africa.

Wallach was a skilled engineer who would spend WWII as both a dispatch rider for the Army auxiliaries and as a tank mechanic. Shilling was also a highly regarded engineer and invented a simple device that helped keep the Merlin V12s of early Spitfires from losing fuel pressure during negative-g manoeuvres; the invention put British fighter pilots on an even footing against the fuel-injected German fighter planes.

Right: A motor transport driver from the Wrens repairs the engine of her car in January, 1943. Photo: Getty Images

The women inspired by these pioneers already had their own motorcycles and knew how to repair them. The WRNS brought riders in off the local racetracks and gave them new purpose. Later, as the ranks grew, less-experienced volunteer Wrens would be trained on motorcycles and learn to ride in the field. (As a brief aside, it should be noted that Queen Elizabeth II learned to ride and maintain a motorcycle as part of her 1945 military service.)

Riding on narrow roads in all weather conditions can be a dangerous enough occupation. Doing so around the clock with the German Blitz going on around you required steel nerves. Training included the expected operating basics, but also extended to evasive manoeuvres required to thread through bombed-out streets, and how to take cover behind your motorcycle if being attacked from the air.

The bikes used were mostly small, single-cylinder affairs, built specifically for military use. BSA, Royal Enfield, and Triumph all produced motorcycles in the 250cc–350cc displacement range, each with modest power. But the bikes were light and agile, perfect for the narrow English country lanes and city streets.

By 1942, the WRNS had stopped recruiting new riders. As German air power weakened, the threat from the blitz waned, though perilous weather, night-riding, and narrow roads remained everyday hazards. The Wrens continued to serve with good humour and a sense of sisterhood. At some point, the orders for the D-Day invasion were tucked into leather messenger bags, and a flock of Wrens fired up their motorcycles and headed out to deliver those historic messages.

This time, after the war ended, the WRNS was not disbanded. Instead, it continued until 1993, when it was eventually absorbed into the British Navy. Dame Matthews retired once the decision was confirmed. In an alcove in Westminster Cathedral, you can find a statue of St. Christopher holding a boat. Upon the boat’s anchor is perched a small wren.

As for the dispatch riders themselves, with wartime over, eventually their services were no longer required. Some returned to civilian life, hanging up their riding outfits for the last time. Some had found new passion and freedom on two wheels. Theresa Wallach, though dispatch riding for the Army rather than the WRNS, continued to ride motorcycles until she was 88 years of age. She died on April 30, 1999, her 90th birthday.

The success of the WRNS as a whole, and of the other women’s military auxiliaries, had the same effect in the UK as women’s greater roles in manufacturing did in the United States. Greater independence had been found, and it would continue to be fought for.

And, for a new generation, the retold stories of the Wren dispatch riders provided inspiration. Perhaps some young woman, reading about Pamela McGeorge, felt her own wrist twisting an imaginary throttle, and thought, “Well, why not? Perhaps someday I will fly too.”

Read more

Your Classics: Patrick Sumner’s 1942 Jeep is a veteran of WWII and family life

11 women who made automotive history

“The most incredible challenge” of racing BRM’s Type 15 V16

Thank you for the article on Wren dispatch riders. A moving and inspirational account.

Thanks for info on women dispatch riders very interesting do you happen to know if a trade badge was ever worn on their uniforms

I work for Western Approaches in Liverpool, home of the Wrens Museum and the Battle of the Atlantic command centre in the war.

How strange that this is posted the same day I have emailed Hagerty to enquiry about group insurance for our historic collection of wartime cars and a dispatch bike!

Would love to chat to someone about cross promotion as we have thousands of visitors to our historic open day with vehicles.

The trade badge for the WRNS Despatch Rider was a circle with the letters MT in the middle.