The transition from 2023 to 2024 seems a fine time to celebrate 30 years of the Aston Martin DB7, which made its first public appearance at the 1993 Geneva motor show and then went on sale in the autumn of 1994. Journalist Andrew English is no stranger to the car or the marque and was on the scene from the beginning as the DB7’s buzz grew into to a low roar that still echoes to this day. – ED

Billed with hindsight as ‘the car that saved Aston Martin’, the DB7 (aka Project XX aka Project NPX) started life as a Jaguar, but needs must when it came to the crisis which had engulfed the old British GT maker in the late 1980s.

Ford had purchased a 75 percent stake of ‘The Aston’ in 1987 for an undisclosed amount at a time when the company was producing the V8 saloon, V8 Volante, V8 Vantage, and Lagonda, with prices ranging from £65,000 to £87,500. Annual production out of the old Newport Pagnell factory bisected by Tickford Street could barely justify such a lineup. In some years, Aston barely built more than 100 cars, in others it produced fewer than half that. The company had been in bankruptcy seven times since its formation in 1913, and by the late 1980s its finances were as robust as a cobweb. Even Victor Gauntlett, the showman/optimist at the head of the company, didn’t believe that a steady living could be made producing handfuls of virtually bespoke monsters. When things were good, the rich came knocking, but when times were tough, they disappeared and Aston floundered.

In short, Aston Martin required fresh investment and impetus – and a new car. It knew this, of course, and along with Bentley, Aston had been teasing the press with the idea of a smaller, cheaper model for years. Ford’s majority share purchase (it took full ownership in 1994) merely fuelled the speculation.

Although while Ford’s chairman up to 1980, Henry Ford II (who was living in England), and its Scottish chief executive, Alex Trotman, might have known all about Aston Martin, Ford’s senior executives didn’t. One of them, interviewed at the Detroit auto show soon after the Blue Oval purchased Aston, didn’t know about the purchase, or what kind of company Aston Martin was and insisted on calling it ‘Austin Martin’.

Yet in comparison to what was to become a financial train wreck of Ford’s ownership of Jaguar and Land Rover, Aston Martin was very small beer. This was a time when the leading lights of American carmaking were loading themselves up with once-distinguished European car names. Chrysler had purchased Lamborghini, General Motors owned Group Lotus, and Ford had failed to purchase first Ferrari then Alfa Romeo, which went to Fiat. Ford was partly goaded by General Motors into buying Jaguar for $2.5 billion in 1989 (generally reckoned to be about $1.2 billion more than it was worth) and then ploughing at least another $30 billion into Jaguar and Land Rover before finally throwing in the towel and selling both companies to Indian conglomerate Tata in 2008 for $2.3 billion.

With all this going on, keeping a low profile was the watchword at Newport Pagnell, and the ostentatious Gauntlett was soon replaced by wily former newspaper man Walter Hayes, who’d steered Ford into racing and eventually Formula 1 and had been partially responsible for persuading Henry Ford II to stump up for Aston Martin in the first place.

If Aston Martin had been looking forward to some transatlantic bounty out of Ford, it was swiftly disabused. “There was no money,” said Hayes as he waved his pipe at me when I interviewed him around the time of the DB7 launch in 1994. As if to prove it, Hayes’s redoubtable assistant Barbara Prince and I had fixed the wheezing central heating boiler at Sunnyside in Newport Pagnell just half an hour before the interview; the board room still had a chill, which wasn’t entirely assuaged by Hayes’s cheerful welcome. I recall him telling me how he’d got permission to use David Brown’s initials on the DB7 – one great saviour to another. Sadly, Brown died in September 1993, six months after the DB7 broke cover.

So, Hayes took on the role of James Garner’s “Scrounger” in the movie The Great Escape. Can’t afford an all-new car on a new chassis platform? What about the Jaguar XJ41, a canned proposal for a replacement for the XJS designed by Geoff Lawson and Keith Helfet? Tom Walkinshaw, Jaguar’s racing supremo, had proposed a new life for the XJ41 body on top of XJS running gear, which he thought had plenty of life left in it, and he employed the talented young designer Ian Callum to work his felt-tip magic. When Jaguar lost interest, Walkinshaw and Hayes brought a DB5 into the studio and asked Callum to make XJ41 into an Aston Martin, with Neil Simpson charged with creating a cabin.

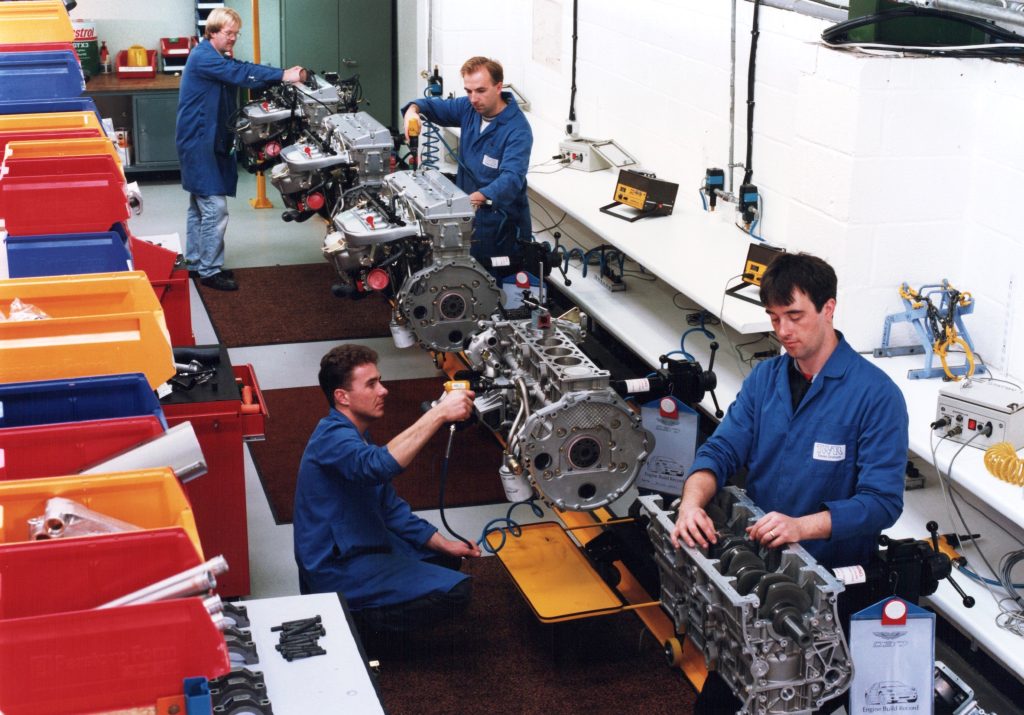

Can’t afford a V12 for your new car? Hayes had a soft spot for a twin-cam straight-six, and he had experience with supercharging from America. That repurposed Jaguar AJ6 engine with an Eaton supercharger on top meant a new front subframe had to be created to lower the engine. As Callum tells it, Walkinshaw had a fully working prototype built in just three months for the Ford board unveil. But by the time the car made its debut at the 1993 Geneva motor show, Dearborn’s suits only approved the car’s development, not its production. I was there when it broke cover in Switzerland; it was a sensation and undoubtedly the star of the show, eclipsing everything else, including Ferrari’s 348 Spider.

“What a stunning car,” whispered Jeremy Clarkson as he sat for the first time in the DB7 for BBC’s Top Gear programme. It was.

The launch took place in the UK, starting at Walkinshaw’s Bloxham production facility (renamed Aston Martin Oxford), taking in an overnight stay at Goodwood, where journalists were encouraged to drive the famous old airfield circuit under the guidance of racing driver Peter Gethin.

Then the real test cars went out to the magazines. I was at Auto Express magazine at the time, where the road-test team of Angus Frazer, Kathy O’Driscoll and former Hagerty editor James Mills conducted a road test, including laps at the unforgiving Millbrook handling circuit. In truth, it was a bit soft in that early form, and the steering was too sharp for the springing on the all-wishbone suspension, giving an over-lively feel to the car if you were driving it on a track. Other road testers thought so, too, Autocar magazine’s testers and racer/Top Gear hot shoe Tiff Needell included. Oh, and I hated the seats, which were bulky and spongy, while the rear seats were unusable for anyone with legs.

While the rumoured price had crept up, in the end the DB7 came in at £78,500, with a sizeable options list. Not cheap, but as they say, a lot of car for the money. The 3.2-litre, 24-valve six pushed out a well-balanced 335bhp and 360lb ft, enough to propel this 1,750kg coupé from 0 to 60mph in 5.8 seconds and on to a top speed of 157mph. The Government economy figure at 56mph was 32.8mpg, though we achieved just 16mpg.

And on the road, the car was sensational, with a nicely judged ride quality, but not at the expense of its lithe and wieldy handling, which allowed the DB7 to cover country roads with swiftness and control, but also swallow miles on longer journeys. The five-speed gearbox was heavy, its change a little obstructive. And the boot was on the small side, but on the whole, we loved it.

Notwithstanding the Jaguar underpinnings, spot-the-parts experts also identified Mazda 323 taillights, Ford Fiesta switches, Mazda MX-5 side lamps, and countless other borrowed bits and pieces, but carmakers had been doing this for yonks. In the modern era of carmaking, developing bespoke small parts for a short production-run car could drain a budget dry, so it was how you incorporated the borrowed bits which counted for more. Less forgivable was a fire in the Autocar test example, which was the result of a poorly fitted exhaust pipe. These things happen…

The rest, as they say, is history. At the time of the DB7 launch, Aston Martin had produced fewer than 10,000 cars in its entire history. The DB7 in a decade of production (1994 to 2004) sold more than 7,100 units, making it the best-selling Aston Martin ever at the time, though that total has since been surpassed by the V8 Vantage and by the DBX. The DB7 spawned the V12 Vantage version, along with the drophead Volante and various hepped-up versions. It was superseded by the DB9, which was an altogether more planned car, but you shouldn’t hold the DB7’s mongrel background against it. For it was not just a lovely looking and fine driving car – it was a saviour of the marque.