It must have been a moment of madness that resulted in my suggesting to my Hagerty editor that I write a column about the Austin Allegro. What on earth was I thinking of? Indeed, is there much more to add to the screeds of words produced on what is generally seen as a 52-year-old joke of British motor making?

This was a medium-sized family car code-named ADO67, which missed targets, hopes, and deadlines with the comic inefficiency of the home guard of Walmington-on-Sea depicted in the Dad’s Army sit-com. Dad’s Army was first broadcast in 1968, the year that chief executive engineer Harry Webster joined Leyland Motors (later BLMC) from Triumph.

On checking the plan chest, Webster, a talented engineer, found it empty. At Triumph, Webster had been responsible for the development of the Triumph TR series, the Herald/Vitesse, and Spitfire/GT6, and for bringing in Italian stylist Giovanni Michelotti to add vim to the cars. Webster was later awarded a CBE for his services to the motor industry. In other words, he knew his onions, and the moths that flew out of the BLMC product plan file as well as the history of cancelled models and stop-start-stop projects must have left him flabbergasted.

This was five years before the 1973 launch of the Allegro and on the eve of the ’68 BMC/Leyland merger. But more importantly, it was six years after the 1962 launch of ADO16, which as the Austin 1100 and Morris 1100 had been world-beating best-sellers. Based on the front-drive A-series engine plans devised by Alec Issigonis for the Mini, in a 12-year production run, more than 2.1 million 1100s were sold. Over half of them were sold in the UK despite the little car’s propensity to recycle itself as rust within a few short years. Forget the wonders of Ford’s conservative rear-drive engineering in the Cortina, ADO16 was an amazing little jalopy sold with not just Austin and Morris badges, but also Riley, Vanden Plas, Wolseley, and MG on the front.

My great grandmother Laura, a formidable driver and pretty handy mechanic, had one, and after her Rover P3, it must have seemed like a space shuttle, albeit one with a bouncy ride thanks to its Hydrolastic suspension. Her comment on the little car’s frugality was this: “The petrol gauge must be broken as it doesn’t appear to move at all.”

So what on earth had been going on at Austin in the time it should have been getting on with an 1100 replacement? Certainly, there was a planned facelift, ADO22, devised under the leadership of Roy Haynes, who was newly hired out of Ford and working out of the studio at Pressed Steel Fisher in Cowley. There was even an Antipodean design with a full tailgate, YDO9, which was going to be a Morris 1500 and Nomad. As ace Rover watcher Keith Adams puts it in ARonline: “It is entirely reasonable to assume that a combination of the ADO22 and YDO9 design could have kept the basic ADO16 at the top of the sales charts with minimal outlay.”

And at the same time, it could have got on with a full replacement for the Mini and ADO16, which under Haynes’s plan would have shared a floorpan.

Events, however, changed all that and BMC was hit hard by the first post-World War Two monetary crisis, which resulted in a credit crunch as governments restricted the interest rates that banks and building societies could offer to lenders. BMC posted a £7.5 million loss in the first six months of 1967, and in 1968 Harold Wilson’s new Labour Government, heavily influenced by newspapers and pundits, helped sponsor a merger between what had been renamed to British Motor Holdings and Leyland Motor Corporation.

An ageing car lineup, parlous industrial relations, competing dealer networks, clashing management visions (and in cases some pretty lacklustre management overall), and a few truly mad decisions marked out the merger. ADO22 was scrapped as Leyland’s stretched resources worked on the Marina, the fleet answer to Ford’s Cortina Mark II. The irony here is that when the 1.3 version of ADO16 was launched in 1968, it knocked the Cortina out of the sales park.

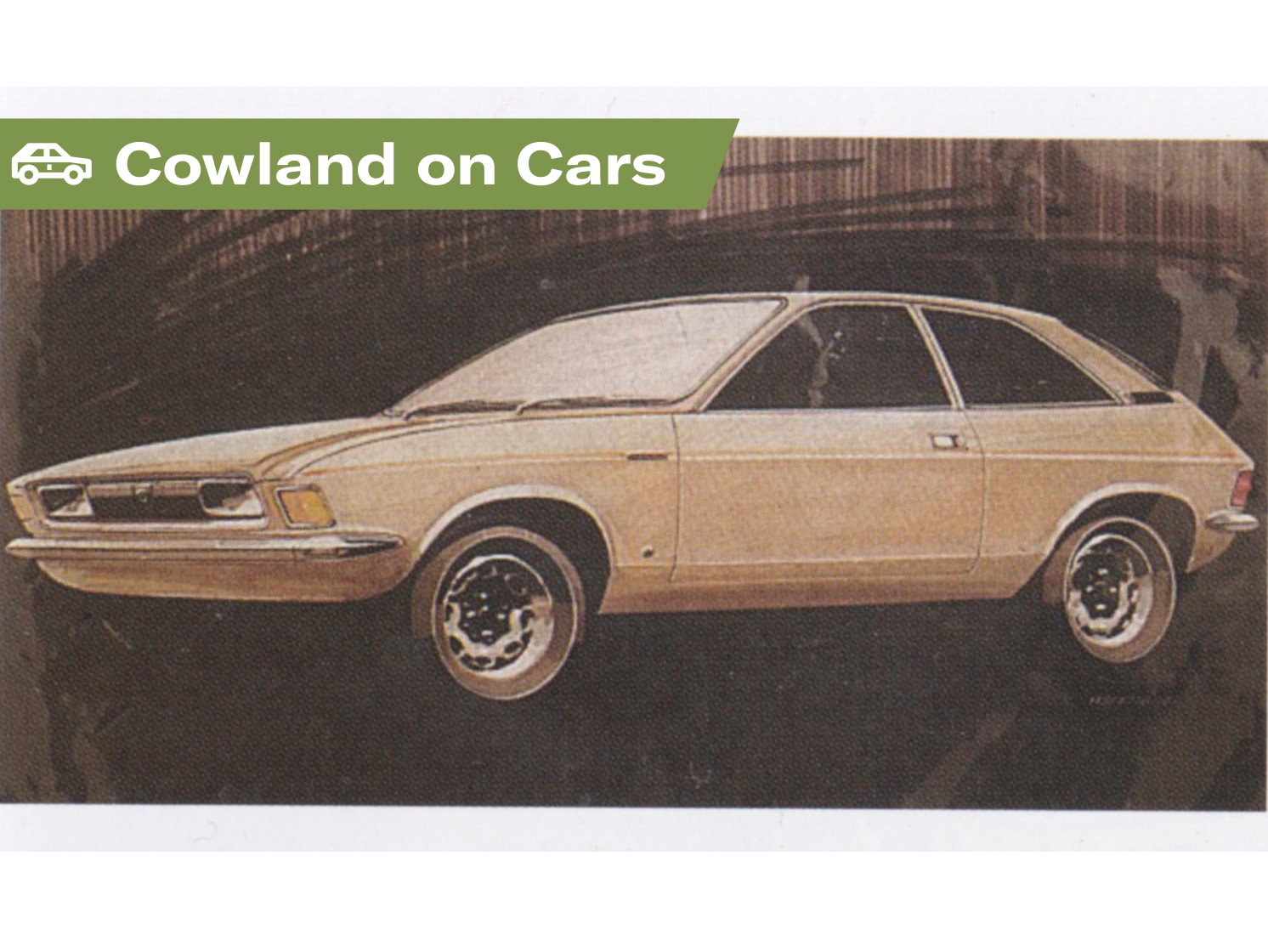

And slowly in tobacco-stained drawing offices, the Allegro took shape. Inspired by a sleek drawing from Harris Mann, the talented stylist poached from Ford in 1968, the Allegro when it appeared looked a lot different.

Speaking to Martin Buckley for The Daily Telegraph in 2015, the then-70-year-old Mann recalled: “Looking at what they [BMC] were making, it seemed a godsend of an opportunity, because there was so much to sort out.”

Under Donald Stokes’ master plan while Morris would be a fleet car maker to compete with Ford, Austin would be a technology and design leader. Stokes told the dealer body as much in 1968, but wow, they took their time. And even then, the sharing of components stymied Mann’s sleek design, with bulky engine-over-transmission layouts and oversized shared heaters raising the bonnet height.

“The heater made the scuttle higher, then when the twin-carb engine went in it made the thing sky high,” Stokes said. “As time went on it was getting loaded with all kinds of safety requirements that the 1100/1300 had never had to deal with. And then they wanted to make it more luxurious looking, with big, fat seats that robbed the knee room.”

Turns out the infamous Quartic steering wheel was engineering’s way of giving a clear view of the instruments while allowing more leg room in those fat seats.

Yet when you see an Allegro on the road today (rarely, I will admit), it is compact, just 3861mm long, 1600mm wide, and 1397mm high, on a wheelbase of 2438mm. All of which give it quite pleasing proportions as well as nifty agility on today’s roads, where massive SUVs of about twice the size bully everything else.

A-series engines, first launched in 1951 in the A30 saloon, formed the backbone of the range, in 1.0-, 1.1-, and 1.3-litre displacement, with four-speed gearboxes. The other option was the overhead-camshaft E-series in 1.5- and 1.7-litre displacement, with optional five-speed transmissions. Both power units, however, had gearboxes under the engine which forced up the bonnet lines.

Autocar magazine’s test of the three-door 1.3-litre Super model wasn’t entirely complimentary, with comments about the snatchy and baulking gear change as well as the pitch and dive of the Hydragas rubber-and-fluid suspension, but the testers thought the PVC-upholstered seats were comfortable and cornering was roll free. The verdict was that the Allegro was a step on from the 1300 and would sell well.

Bill Boddy at Motor Sport magazine tested the 100mph 1750 HL model in 1975, concluding: “I feel that it stands up well against comparisons with Continental and Japanese products and that those wanting a quietly-appointed, very accelerative four-door package might well invest in this Allegro HL, which will cost you a matter of £1,881.”

But the buying public preferred the brash space of the Cortina, or Giugiaro’s folded-paper design for the VW Golf, which hid some very ordinary components.

Prelaunch dealer brochures for the Allegro billed it as “a new driving force from Austin,” but that proved to be hubris in the purest form. Just 642,350 were made during its decade-long production life, which was far short of the plan. Even worse, most were sold in the home markets rather than what was hoped to be appreciative world markets.

In the UK, the Allegro bobbed around between seventh and fourth in the sales charts throughout the 1970s. The 1975 Allegro 2 answered a number of the niggling faults of the original. The 1979 Allegro 3 was a pretty good car, well built with decent reliability, but it was too little too late. British Leyland had collapsed in 1975, and the company was nationalised, renamed the Rover Group in 1986 and sold to British Aerospace in 1988. The Allegro became a source of national car-making shame, unfairly carrying the blame for a lot of things gone wrong which it could have had no effect on.

I was at school when the Allegro was launched and did several driving lessons in a late Allegro 3 model. I can attest to the baulking gear change, scourge of nervous hill starts and three-point turns, but otherwise it was easy to drive, the seats were comfortable, and it was a good-looking little car for the time.

Though they didn’t rust too badly, the stressed inner front wings, subframe-based suspension, and poor heater draining meant many have since succumbed. If you fancy a dip into Allegro ownership, pick the best you can afford, as spares, particularly body panels and trim, are rare as spectacles for donkeys.

At the time of writing there’s a pristine-looking Vanden Plas 1500 model on sale at a dealer in Nottingham at £8,500. Rather a lot, but a classic nevertheless.

What a great feature on the Allegro, I remember attending the launch of the Allegro in 73 at our local British Leyland dealership with my parents ‘Timberlakes of Wigan’ . I was only 9 at the time, we didn’t buy one, stuck with our HC Viva.

My dad had a 1.3 in Tahiti Blue and a 1.5 in Russet Brown. Both were great cars and much better than the newly arriving and tinny Datsuns, or the bland Vauxhalls and the so-called Dagenham Dustbins of the time. Only the Renault 16 was better but that was already a bit of an old dowager. History has unfairly judged the Allegro. It is easy to look back and sneer but it was an innovative design and a competitive car in its day, particularly the special edition LE that came in only two colours, or the marvellously pompous Vanden Plas, driven by the sort of people who bought the show home on a new housing estate.

Thank you for a very interesting and nostalgic read. When you said your great grandmother had owned an Austin 1100, I calculated that you must still be a teenager.

In 1979 i bought a 1974 Allegro 1750 SS, Against my better judgment i think i bought it because it was very well specified with a full sun/vinyl roof, 5 push button radio cassette player, head rests all round, electric ariel ! 5 speed gear box as i recall and front fog lights. I had never owned a car before that with so much on it. I test drove it and thought it was ok and would do. It was relatively inexpensive compared to other vehicles with similar specification.

After about only one week and about 200 miles i hated it. And i really started to question why i ever thought it was a good idea to buy one of these, especially as i was in the motor trade and knew these cars had a reputation. I carried out a few cosmetic repairs to the body work that needed doing, and within 3 months i had sold it.

Interestingly though i did sell it for a profit and i was worried i was going to be stuck with it.

I owned an Allegro, very economic to run but the hydrogas suspension needed to vist the dealer every few weeks, soon parted with it for the first of my three new Capri’s, bliss!

Select models were very nice indeed eg the 1500 VdP with auto gearbox. Beautiful

The Allegro was a sneeze, a symptom of the industry’s malaise, which all industries, especially state industries have, just as all children catch colds. Ford as a private business survived by personal forces of responsible family personality.

I was present at the Allegro press launch for northern journalists at The Majestic Hotel in Harrogate. We gathered in the ballroom, and as usual the cars were present, but covered with wraps. The director of sales for Austin-Morris, Filmer T.Paradise — yes, what a name! — gave an introductory speech, talking up “The Product” that he was about to show us. “The Product” would be not only a sales success in the UK, but also a world-beater… everyone would be wanting to own “The Product”. There was quiet muttering amongst the hard-bitten motoring journalists… we’d come to see a new car, not a ‘Product’. And what was a ‘Quartic Steering Wheel’ anyway?

Eventually the build-up finished, the fanfare played, and assistants came forward and whipped off the wraps, to reveal…..a Product! No style, no pizazz… it was indeed a ‘Product’. And it had a square steering wheel! As a unique selling point it was just that… unique, but hardly practical.

We all went out to the car park to collect our Allegros (Allegri?) for a test run in the Yorkshire Dales. I confess I didn’t go far in mine, but turned back to The Majestic, making some excuse about having to get back to the office to file my copy (which, if I recall, made mention of the fact that the rear quarters had distinct echoes of the FIAT 127). We all knew this wasn’t the world-beater that Mr Paradise was dreaming of. After a few months the steering wheel was quietly changed for a round one.

You’re right… it’s great to see, very occasionally, one on the road on the way to an event. It’s one of those cars were you’re delighted that someone has preserved one… but just very glad it’s not you.

Call me weird but the car I joined the RAF with to start my flying career was an Allegro. I loved it but at 18 you love what’s yours rather than what’s your parents’ (Alfa Sprint Veloce). I chopped it after a year for a Midget to fall in line with my MG/Triumph/Ford driving colleagues but still have a lot of fondness for Allegros.

I once had a late Allegro 1.0 with the A+ engine from the Metro, in basic ‘L’ trim. It was actually a decent car – economical, reliable. It had a round steering wheel! I do think the general negative feedback about the original quartic wheel is misplaced. So many new cars today have them, for exactly the same reasons – to improve kneeroom and dashboard visibility, but I never hear anyone ‘knocking’ the idea. A sad case of BL bashing I fear.

I had an Allegro estate for five years and it never once let me down as a young family with two small children it was the perfect family car, very comfortable and reliable. We went to Brittany every year and made regular trips from our home in Lancashire to see our friends in Southampton. Mind you it was a bit of a shock after selling my Mini Cooper S rally car when our first baby arrived.

Back in the day I rarely followed an Allegro that wasn’t leaving a faint trail of blue smoke.

I had a car hire business in the early 80s and ran new Fords, Vauxhalls and Austins. I was persuaded by one of my suppliers to take an Allegro 1000, the last variant with the A Plus engine from the Metro. I didn’t buy it but rented from the dealer. My experience with it was that it was totally reliable, far better than any of the Fords on the fleet, customers, once they overcame their media induced prejudice loved it and, being a 1000, it probably got thrashed up hill and down dale! Fords of the time had the dreadful CVH engine which broke cam belts at ridiculously low mileages, and Sierras had the useless VV carburettors, which a Ford main dealer recommended that we paid to swop for a Weber before taking delivery of new cars! Incidentally, our Maestros and Montegos served us equally well and did 80k and three years service on hire.

The quadriceps steering wheel was ridiculed at the time but it was obviously ahead of its time as so many high-end cars now have square steering wheels.

The quartic steering wheel was ridiculed at the time but it was obviously ahead of its time as so many high-end cars now have square steering wheels.

My neighbour owned and ran an Allegro for over 150,000 miles. He said it was the most reliable car he ever owned.

Lovely article. You might like this piece I wrote a while back http://gt-cars.co.uk/austin-allegro/

I bought a 1978 1750HL because it did 0 to 60 in 10 seconds. This was considerably faster than any of the competition.

The next car I bought was an Alfa Giulietta 1.8 which was 10.8 seconds.

I always thought if BL had been brave enough they could have produced concept. Allegro 5dr (hatchback) fitted with only the

larger engines, with square front

based on the Marina .With moulded

plastic bumpers Raised suspension and larger wheels..

Now that would have taken the press by surprise..

Plus why o why didn’t they make use of the creative companies around the world who quickly produced modified variants of the BL range in the 60s early 70s….

Very poor management decisions, I guess or

Interference from the government.

Before I was old enough to drive, a friend traded in his rusty 1100 for a new Allegro which had just been introduced. I thought it was a definite step backwards. The engine/gearbox mounted without a subframe was so rough and noisy compared with the old 1100 and the interior was horrendously cheap, even by the standards of the mid 70s. The plastic coverings on the sills were coming unstuck while too much glue was smeared over the headlining. The door cards were obviously just that; pieces of hardboard the corners of which could be seen poking out from the split plastic coverings. The 1100/1300s had much better quality interiors. I think that was my only experience of an Allegro and it has remained a dreadful effort in my mind , epitomising all the troubles of the company at the time, mirrored by the Princess, Triumph TR7 and Rover SD1.

I recall seeing an Allegro parked near a London music conservatory. Next to the ‘Allegro’ badge, somebody had felt-penned ‘ma non troppo’. Bene.

I am feeling really guilty now i am reading the other reviews.

My review was an honest one and i cannot change the way i felt about the car i owned.

I am not anti BL, i worked in a Rover Triumph Land Rover distributor who were also BL dealers at other sites we owned.

The Allegro 1750 SS i owned back then was very quick, pretty good on fuel and although i did not own it for a very long time. It was very reliable. No break downs at all in my ownership.

I liked the look of it, and by the time i took ownership the square steering wheel had long since disappeared and a small sporty round one was put in its place.

I just found this car so awkward, the gear selection was so in precise and it just did not fit my driving style. I was never uncomfortable driving it. it got me everywhere i wanted to go, the build quality, the overall feel just did not suit me in them days.

I might be persuaded to own one now i do not have to use it every day.

I grew up near Longbridge and they used to drive them past us as we walked down Lickey Hill on our way home from school as it was the test route once they came off the production line. There were a lot of them around as Longbridge workers got something like 17% off them. I only remember one of them that didn’t have the square steering wheel swapped for a round one. Awful awful things with lousy build quality – soon to be surpassed in a bad way by the Princess.

We hired a new Allegro in the mid-70s when our Citroen Dyane was in for servicing and we had to get to Yorkshire for the weekend from Gloucestershire ( my Alfa 1750 GTV engine was in pieces! ). Lovely car, couldn’t understand what all the the subsequent criticism was about. Mind you, the garage had a poster on the wall about tracing bodywork water leaks…

I had three Allegros when we we’re in the motor trade they sold well my wife used them until they sold never broke down she loved driving them simple and easy to drive but we are always condemning BMC cars but the trouble was when it became British Leyland lack of investment but the brand had the best engines for starting on cold winter mornings so let’s not be too quick to judge after all we have awful electronics that are too complicated ( Bring back simple engineering in car manufacture )

The main ‘photo taken at Kinver Scout Camp Near Stourbridge