From Edsel to Cortina, Roy Brown Jr’s career at the Blue Oval couldn’t have been more ‘gutter to weather vane’. It was the Canadian-American designer – on the demoted bounce after penning Ford’s three-billion-buck flop – who would design the first generation of the UK’s fleet and family mainstay, which would sell over 4.15 million around the world in 20 years, through five different models. Welcome to the Dagenham dustbin, which it turned out, was anything but . . .

In popular culture, the Cortina occupied a unique shorthand. As Ian Dury and The Blockheads sang in their 1978 hit “Billericay Dickie”: “Had a love affair with Nina. In the back of my Cortina. A seasoned-up hyena. Could not have been more obscener.”

Or The Tom Robinson Band with its 1978 number “Grey Cortina”: “Cortina owner – no one meaner. Wish that I could be like him.”

We’ll spare your blushes here and turn to a 1965 interview with Roy Brown Jr in the Ft. Lauderdale Sun Sentinel, when he showed a remarkable degree of sangfroid toward the vicissitudes of working for Ford: “I cried in my beer for two days and then I said, ‘The hell with it. Enthusiasm got me where I was, and it’ll get me back’.”

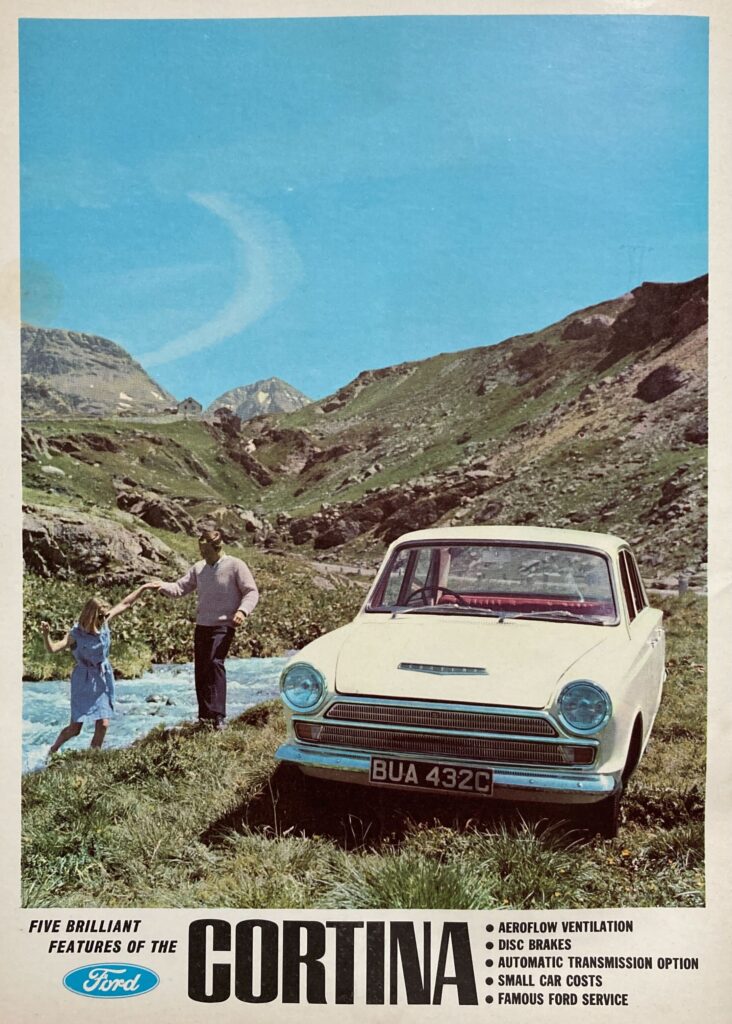

Well, it certainly did. Ford’s answer to BMC’s 1959 wizardry on wheels, the Mini, was the 1962 Cortina, named after the Italian ski resort of Cortina d’Ampezzo, and code-named Project Archbishop. Brown’s Mark I model still looks trim and sassy today, especially with a set of wide-offset steel rims and a judicious bit of body stancing on its MacPherson strut and leaf-sprung solid rear axle.

Engineered, designed, and produced under Irish-born Ford lifer Patrick Hennessy, the Cortina was perhaps one the most cynical cars ever made, but also one of the most successful and, well, just plain clever. Early in my career, I knew several of the Ford executives who worked under Hennessy, the high priest to Project Archbishop’

“Never overestimate the sophistication of the British public,” they’d toast when talking about the Cortina, but I think they did the Ford a major disservice. Like many others, I owned an old Cortina when I first started driving and while it was rusty and unsophisticated, it taught me how (not) to drive and how to look after simple mechanicals.

Because, even if you can forget the far more sophisticated front-drive, independently sprung Mini, the Cortina wasn’t even the most technically advanced saloon of this size (168.25 inches long) in the Ford stable at the time.

It came about as a result of Hennessy visiting Ford’s head office in Detroit at the end of the 1950s, when he became aware of a Ford saloon project which had been handed to Ford of Germany. The Taunus 12M (code-named Cardinal) was a clever thing indeed, with front-wheel drive to save cabin space and a range of V4 engines to cope with high-speed autobahn work. It was scheduled for launch in late 1962, and Hennessy thought that with an amped-up development program and de-contented specification, the Cardinal could be beaten to market in the UK.

What were Ford of Detroit thinking of? Two identical, similarly sized saloons with their own development programs, going on sale at the same time? Sounds a bit like Audi and Volkswagen’s development of two almost identical V6 engines – the motor industry doesn’t really learn . . .

So, the clock was ticking when Hennessy touched down from Detroit at Heathrow. He appointed chief product planner Terence Beckett (later Sir Terence) to the program and Fred Hart, the executive engineer of light cars who’d been key in the development of the Zephyr, the Consul, and the 105E Anglia, which donated much of its mechanical specification to the Cortina.

Critical Path Analysis had initially been devised in the late 1950s by Morgan Walker of Dupont and James Kelley of Remington Rand. This science of melding time scales for marketing requirements, budgeting, design, development, and product engineering into one schedule was in its infancy, but it strongly influenced Ford’s red book for the Cortina. These days, engineering-savvy journalists help devise these new-model schedules, which at some companies are called ‘murder books’.

And that red book certainly worked for the car initially to be called the Consul 225. Hart’s South Ockendon–based team were in charge of the Cortina’s body design and engineering, while Beckett oversaw project timing and the budgets. And pretty much all the targets were met: the overall weight of 770kg (they missed by 20kg); the two- and four-door and estate versions; and the performance from the 49bhp, 1.2-litre three-bearing Kent four-cylinder and four-speed transmission. A top speed of 75mph and 0–60mph in 22.5 seconds seem leisurely now, but they were enough at the time. And if the cabin seemed stark, there was lots of space for fleets and families, along with a large boot. There was also a mid-cycle facelift on the way, the 1963 introduction of the estate, a 60bhp version of the legendary 1.5-litre five-bearing Kent mainstay of so many performance Fords, as well as the famous “Aeroflow” ventilation system.

Right before the initial launch, the Consul 225 name was dropped and Cortina adopted. What seems so familiar now had at the time a daring connection with the Italian resort, which it was thought would help the car’s appeal to European markets. Arguably more tangible marketing included the plan to have a new Cortina model in every dealership to coincide with the launch in the summer of 1962, so that folk could see and touch the new car. It was the same successful strategy adopted by Lee Iacocca for the 1965 Mustang.

And the stunts? Oh my goodness. For the 1964 facelift, a bunch of racing drivers including two-times F1 champion Jim Clark drove a Cortina down the bobsleigh run at, erm, Cortina. Doubtless these days it would be banned by the Advertising Standards Agency, but back in the day it made quite a splash.

As did the 1970 shot of the one millionth Cortina slung under a helicopter on its way to its new Belgian owner. The Cortina was one of Britain’s biggest car exports throughout its life.

The Mark I lasted until 1966, though one of its longest lasting legacies, the Lotus Cortina, was introduced in 1963. Powered by a 105bhp 1557cc version of the Lotus-Ford four-cylinder used in the Elan, together with that car’s four-speed gearbox, this proved a sensation on the tracks as well as in the showrooms, the embodiment of Fords PR supremo Walter Hayes’ adage: “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday.”

Early versions of these white Lotus Cortinas with their distinctive green stripes had alloy panels, shorter struts, servo-assisted Girling brakes, and 5.5J steel wheels with an A-frame rear suspension, but these were soon dropped as being too fragile.

The Cortina Mark II continued the theme, but the square-set body proved not as popular, and the Lotus version was steadily de-contented. These days, a Lotus Cortina Mark I in good fettle will set you back around £30,000 and a Mark II in similar shape around £23,000.

Then came the 1970 Mark III ‘coke-bottle’ shape which unified the Taunus and Cortina platforms, followed by the 1976 Mark IV, and in 1979, the last ‘Cortina 80’ models of which the very last, a Silver Crusader model, rolled off the Dagenham production line on 22 July 1982.

“It lasted from ‘Love Me Do’ to ‘Sergeant Pepper’,” said design commentator Stephen Bayley of the Mark I during a BBC2 special celebrating the Cortina six months after the end of production. Can you honestly imagine an arts program like this these days? Grayson Perry on the Tesla Model 3, anyone?

Alexei Sayle did a skit with John McVicar, and poet laureate John Betjeman recited his poem Executive: “I am a young executive. No cuffs than mine are cleaner / I have a Slimline brief-case and I use the firm’s Cortina.”

“The Ford Cortina; a car above comparison,” ran Ford’s ad line. Patently not true, although the Cortina overtook the Austin Morris 1100 and 1300 as Britain’s best-selling car in 1967, and it was the best seller in nine of the 10 years between 1972 and 1981. Ford sold more than 2.6 million Cortinas in Britain in its run, and even decades after its replacement, it was still one of the best-ever selling cars. Rust eventually took care of the remaining examples, and a genuine unrestored Cortina is a rare sight these days.

The Sierra hatchback that replaced it saw the end of the mid-sized saloon for Ford, a situation Ford was forced to address in 1987 with the Sierra facelift.

What Betjeman, Sayle, and Bayley understood, as well as The Clash in “Janie Jones” and Elton John in “Made in England,” was that the Cortina was shorthand for a particular type of life and times. The GXLs, the vinyl roofs, the different wheels and grades of velour upholstery all minutely tracked Britain’s class system. And while most Cortina owners were middle-aged salaried married men, like most of us, they all imagined they were a cut above and that their car reflected that.

Besides, even if you’d never stepped foot inside one, for well over 20 years, a Cortina formed the backdrop of our lives, like the Escort which followed it into the best-seller lists, or the Fiesta after that.

For all of Britain, for two decades and more, the Cortina was more than a car. It was the scenery.

Two songs you missed. The Lambrettas ( cortina) about the mk2, approx 1980. And of course the classic Elvis classic Track. Cort in a trap! Seriously though great feature on a car 99% of people loved. Myself included.

I just read your article about the ford Cortina.I had a mk1 mk 2 a mk 2 Lotus and mk 3 1600cc.The Lotus was some machine.I took the engine out of it and put it in to a mark I Escort for rallying.