What does pop music have to tell us? Quite a lot, it appears, since in May 1963, coinciding with the launch of the Hillman Imp, the Beatles were at number one in the charts with From Me To You, whereas in March 1976, when Project Apex finally met its nemesis, slipping into fourth place in the hit parade was Barry White’s You See The Trouble With Me.

With fewer than half a million units built in 13 years of production, the Imp’s history is filled with premonition and omens. The car was designed by Mike Parkes, a talented engineer who went on to drive for the Ferrari Formula 1 team, and engineer/designer Tim Fry, and the prototype was given the moniker the Slug, which was, let’s face it, a terrible name. The little Imp was one of the first mass-produced cars to be sold in Britain with an all-aluminium engine based on the Coventry Climax fire pump unit, itself inspired by the aluminium Sunbeam S7 motorcycle engine. But did we yet understand the importance of inhibitor in such units to prevent the waterways sludging up with minerals and corrosion? Did we hell.

I recall them on the roads of Lymington in Hampshire, a genteel sailing town situated between The Solent and the New Forest. They were bought by retired folk looking for an alternative to their Minis; richer pensioners bought the luxury Chamois derivative, and racier pensioners the more powerful Stiletto coupe. Back then the Imp was a bit of a shock of the new, especially with that Corvair-like grille-less front and the opening rear window which we had never seen before, though the ‘Breezeway’ opening rear window had been introduced on 1950s Mercury and Lincoln models.

In a test for Modern Motoring and Travel in May 1963, double F1 World Champion Jack Brabham noted, “the rear window section is hinged, so that luggage can be put into the car with the greatest of ease”.

We called it ‘the escape hatch’ after a friend’s brother had a big off on the coast road to Barton and, although mildly injured, he’d had a lucky escape having been thrown out of the rear window while the little Imp had caromed off a massive oak tree.

They certainly did things differently back then, though just how differently you’ll have to judge. Curated by the hilarious Richard Herriot, Driven To Write claims to have unearthed a December 1963 road test from Archibald Vicar, motoring correspondent from The Practical Car Driver (though there are some who say that Vicar is actually George Bishop and others who say he’s a gentle piss take on the lines of Troy Queef from Sniff Petrol).

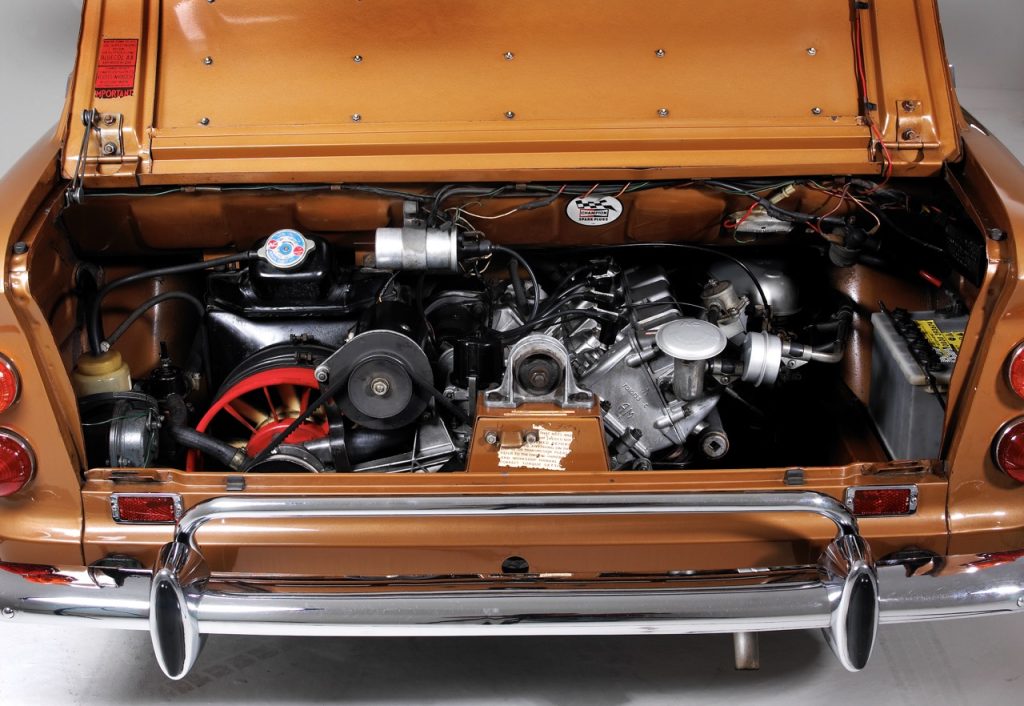

Anyway, whoever he is or isn’t, Vicar arrived at the Imp factory at Linwood in Scotland to drive a route chosen by the spin doctors at Rootes. It consisted of a tour of the local distilleries with a test of how many bottles of single malt he could fit under the bonnet – the Imp was rear-engined remember.

It sounds like an eventful test, with the passenger seat working itself loose, a cheeping steering column, a self-detaching rear window, and Vicar misjudging a corner and entering a ploughed field. There’s no mention of whether, as they say, “drink was taken.”

In addition to this, Vicar was distressed to find the ashtray had worked itself free. In fact, he had some harsh words for little car’s ashtray and rearview mirror: “Lady motorists must take note that the Hillman Imp’s ashtray is slightly hazardous to long nails. The rear mirror is rather small which will mean that adjusting one’s make-up in the car is not all that convenient.”

Back in the more conventional road-test world, in May of the same year, when The Autocar tested an 875cc Imp de luxe, the tester noted that “many aspects of the new Hillman Imp . . . are quite novel for a British car.”

They certainly gave the little car the treatment, achieving an 80mph top speed and 22.7-second 0–60mph acceleration in the 711kg test car while at the same time achieving an average fuel consumption of just under 40mpg.

“The engine is particularly impressive for its complete freedom from vibration and its eagerness to turn at high revs,” praised the road test.

Brabham was particularly taken with the engine, too, writing that the unit had been developed out of a 750cc Climax Feather Weight race engine, which in the Lotus Elite won the Index of Performance award at the 24 Hours of Le Mans for six years. He thought the 39bhp unit was “delightful” and despite driving it hard, still managed over 40mpg.

Imp rivals included not just the Mini, but also the Renault 8 (1962–73) and the NSU Prinz4 (1961–73). The Imp was advanced for its years, however, and not just for the aluminium engine mounted in line with the body, but also for its semi-trailing arm independent rear suspension. The brakes were drums all round, though, and the swinging-arm front suspension had marked positive camber and a very high ride height, particularly on pre-1967 cars. Imps had some eye-watering handling characteristics, and we used to say a sack of potatoes under the bonnet did wonders. De-camber kits were widely advertised at the time, as was converting to the stronger suspension of the Sport models or ugly Husky estate.

There’s a great quote on The Imp site from Apex: The inside story of the Hillman Imp, by David and Peter Henshaw. The two authors interviewed Tim Fry, who recalled demonstrating the Imp to a representative from Chrysler just prior to the 1967 takeover: “And the silly American said to me, just as we were coming up to this roundabout, ‘Do these things understeer or oversteer?’ And I said, ‘Well, I’ll show you on this roundabout’.

‘You can make it understeer like this, (and we went round the first roundabout), ‘or you can make it oversteer like this.’ And he was completely silent after that.”

Fabulous!

All these fuel-sipping tiddlers were genuine attempts to get more out of a gallon of fuel after the Suez Crisis of 1956, when the Arab states discovered just how much control they had over Western economies if they turned off the taps, and Britain discovered just how little autonomy it had in the world without the backing of America.

Against a backdrop of falling car sales, small cars with engines of about one-litre capacity saw sales quadrupling between 1956 and 1957. Carmakers reacted by commissioning small and economical cars, though not exactly bubble cars, which was a criticism levelled at the Slug when it was first shown to Rootes Group bosses. Although, with commendable prescience, they’d commissioned a small car project in 1955.

Parkes and Fry had a list of priorities for their design: accommodation for two adults and two children; a 60mph maximum speed and 60mpg economy; rear-engined layout; and fun to drive.

Anyway, the board didn’t much like the Slug. As Keith Adams reports in the reliably reliable AROnline, “allegedly, Lord Rootes hated the sight of it so much, he refused to ride in it.”

But they did want a small car, just not one that looked cheap, utilitarian, and bubble-ish. Project Apex was the answer, a bigger smaller car under the leadership of technical director Peter Ware. Coventry Climax were approached for an engine and Fry managed to shoehorn the motor and gearbox into the prototype known as Little Jim. Detuned to 39bhp and increased in capacity to 875cc for road use, the overhead-cam engine drove through a four-speed transaxle. But with the Mini, Alec Issigonis had already proved that brilliant design trumped a brilliant drivetrain. Launched in 1959, the front-wheel-drive Mini had old fashioned pushrod A-series engines that shared the same oil as their transmissions, but as Ford’s Richard Parry-Jones would often observe: “Execution is always more important than conception.”

Making all the Imp innovation work cost time and money, and in the end, Rootes was forced to push its little car onto the market. It then became enmeshed in government regional policy and was forced to build a new factory in rundown Linwood, near Paisley.

The car was rushed into the market too fast and innovative features such as the pneumatic throttle weren’t properly tested. Water pumps failed, automatic chokes went haywire, there were water leaks and overheating problems, and while the Mini was being developed with ever faster Cooper derivatives, Rootes were all out just keeping production of the standard car on track, with poor management versus Bolshy unions and production logistics that defied sense and belief. As John Simister, friend and Imp owner, noted in an article for Motor magazine, “The cylinder blocks for the die-cast engine were cast in Linwood, but had to be sent down to Coventry for machining and assembly and returned to Scotland for installation.”

By the time the Imp was sorted out, the Suez had faded into memory and big cars were back in favour. Ford’s Cortina made more money than the Mini and a lot more than the Imp. “Small cars, small profits,” Henry Ford II is reported to have said when the first Fiesta drawings were presented to him.

To drive an Imp today is to recall an era of fantastic and ambitious engineering together with overarching optimism. That free-spinning engine is a thing of wonder, the ride is quite lovely, and with such thin windscreen pillars, the views out are panoramic. Not so good is the performance, which even in tuned cars is modest. The seats and driving position aren’t the most comfortable, and to drive an Imp is a noisy experience. There’s also the passage of time on the components, which today means you’re never quite sure if you’ll get to your destination. Membership in the Imp Club seems a must.

Hindsight is wonderful, but there were warning signs for the Imp in period. The lesson of a car never making good after a poor launch still stands today, as does the public’s reluctance to spend more on innovation when it gives it no immediate benefit. There are many who say that the Imp forced Rootes into the arms of Chrysler, leading to its ultimate demise.

The Hillman Imp is a rare sight on the road these days, but to see one is to see a car that still looks perky and somehow more modern than the Mini. Just far, far less successful.

I had 3 IMps; they all had problems but were fun and driveable; the third was called a Rally Imp with improved suspension and more power and was the best of the 3 and I would happily drive it today. Unfortunately, my wife of the day crashed it.

Full English – built in Scotland. I had 2 – Chamois and Commer van. Don’t forget the 998cc/fastback versions. Part of the ownership fun was going to a petrol station to watch the pump attendant wander all round looking for the filler cap actually hidden under the bonnet.

A car with a special memory for me ! I was part of a team testing the two prototype cars then called ‘APEX’ during August 1962 based at Invergorden Scotland .

The two prototypes were simply known as L1 and L2 !

Dear all, Many thanks for the comments. Sorry to be so slow in answering but I’ve moved but my internet service provider is having trouble keeping up. So Ian, yes, I was always puzzled at how many were crashed. I wonder if the rear engine gave an unfamiliar weight balance. Did rust take more of them than impact? Hilarious Chris and much respect to you Doug. All the best, Andrew

Great little cars. I had Imp, Imp Sport, and Stiletto all used for motor sport also achieved best overall performance on 1966 Mobil Economy Run of 1084 miles at 54.37mpg in a factory loaned Imp. Imps had better traction “off road” than Mini!

I had 2 Hillman Imps and loved them both. One was the bronze colour shown in the pictures above. I remember the first one I drove with a scrambles (moto cross) bike on a trailer behind coming down a steep mountain incline followed by a sharp left hand corner, and having to stand heavily on the brake pedal just to make the corner. I fitted a servo on the brakes after that!

I had no trouble with both my cars, except for rust appearing on the window sills.

In the late 1960s I remember seeing an Imp being driven over a tank testing area on TV. Was this the first car TV advert, as I was very struck by it?

The engine was also used to power the generator for the BAC Rapier missile surface to air missile system.

” The Full English”. Nonsense ! Is your writer not aware that Imps were built in SCOTLAND ?

Our writer, Andrew English, for whom this regular column is named, is quite aware. He even says so right in the story…

Don’t forget the Imp based Zimp!

https://www.imps4ever.info/specials/zimp.html