What’s the first Rolls-Royce Phantom like to drive? In a word, stately; a little like all the subsequent Phantom models, including the first BMW-developed model of 2003.

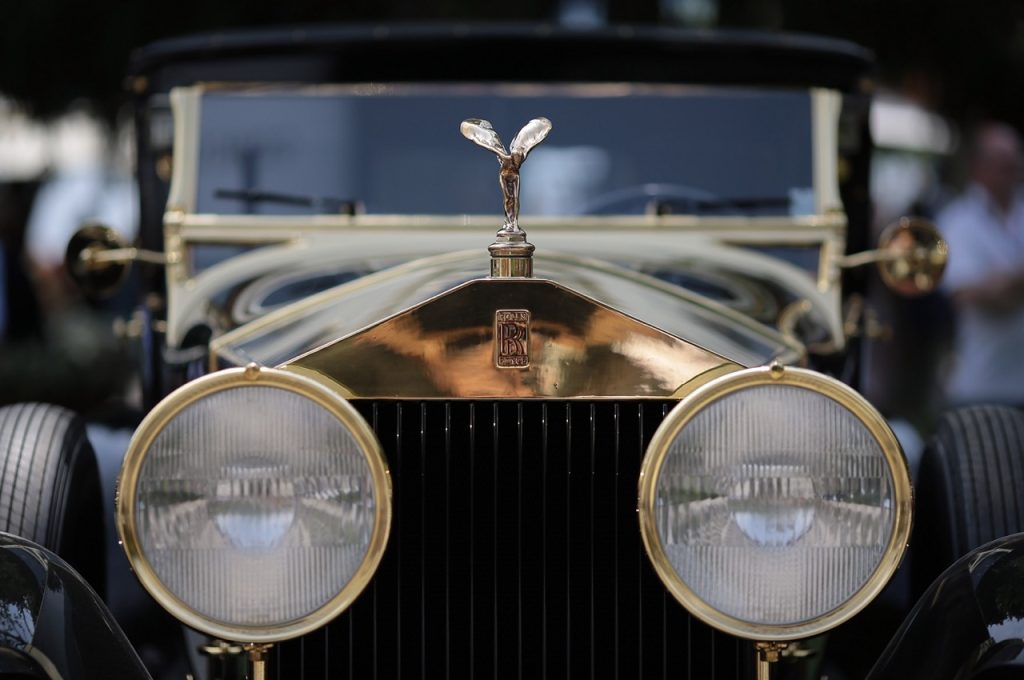

The 7.7-litre six crackles discreetly as it starts, a bit like the soft sizzle of paraffin-soaked newspapers igniting under a bonfire of autumn leaves. Compared to a contemporary Bentley, there aren’t many instruments on the wooden dashboard, and the needles move gently as befits the first of the breed – and indeed any car that follows the Spirit of Ecstasy mascot.

The engine revs slowly and the car gathers speed surely and irrepressibly, like that seventh wave foaming up the beach determined to catch you and fill your wellingtons.

Then comes time to change gear and the refined progress is interrupted as you grapple with the sliding-pinion four-speed. No two are alike, and at first some Phantoms are undrivable, except by their owners, who seem to surpass the clash and gnash of gears and slide the lever through like a teaspoon stirring a porcelain cup of lapsang souchong.

The main aim is to get up into top gear and then use the ignition advance and mixture control to let the big engine do the rest. With each aluminium piston displacing almost 1.3 litres, pulling power is not an issue.

The brakes are pretty good, but you don’t really use them, instead drafting this big car along like a Venetian gondolier slipping his charge under the Rialto Bridge. It’s a different style of driving, not always appreciated by the modern motorist, but more suited to a French Routes Nationale, old turnpike routes through national parks, or straight German A roads traversing the plains under the Alps.

Refinement, yes, utterly, but technological sophistication? Forget it. In 1925, when the Phantom I made its debut, Rolls-Royce finally caught up with the 1904 Buick Model B and fitted overhead valves to this replacement for the old 40/50 Silver Ghost, which was only subsequently known as Phantom I. It’s a measure of the innate conservatism of Henry Royce that it took over 20 years to get round to it…

His command to “strive for perfection in everything you do. Take the best that exists and make it better,” might be one of the most famous motoring aphorisms, but if you abide by it totally, you’ll spend a lot of your time catching up with your rivals in what was even then a fast-moving industry.

For while the head of Rolls-Royce’s test and experimental department Ernest (later Lord) Hives had written to Henry Royce in 1922 saying: “we expect that we shall get beaten for pure speed and hill climbing, when we compare against cars with larger engines,” the fact remained that even the very rich didn’t like being overtaken by cheap Buicks, or Vauxhalls for that matter. And although competition for the big Rolls-Royce model had once been only the Napier, Hispano-Suiza and Isotta-Fraschini were making inroads into the Silver Ghost’s market, and W.O. Bentley was about to enjoy an injection of cash from entrepreneur Woolf Barnato…

Times, they were a-changing, or as J.R. Buckley puts it in his deliciously snobby Cars of the Connoisseur: “In the post-war [WW1] world, in which values were to change more in three to four years than they had in the preceding 40, where reputations were as ephemeral as the tropical sunset…”.

Such was the position with the Ghost in the early 1920s, when despite Henry Royce’s determination to produce what he thought of as the best cars for the market, the Rolls-Royce board finally accepted the inevitable and commissioned a new car. This was brave at a time when sales were slumping, though in 1925 when the new Phantom was introduced, the main differences between it and the Silver Ghost were its engine, its front brakes, and a different way of mounting the steering column to the chassis.

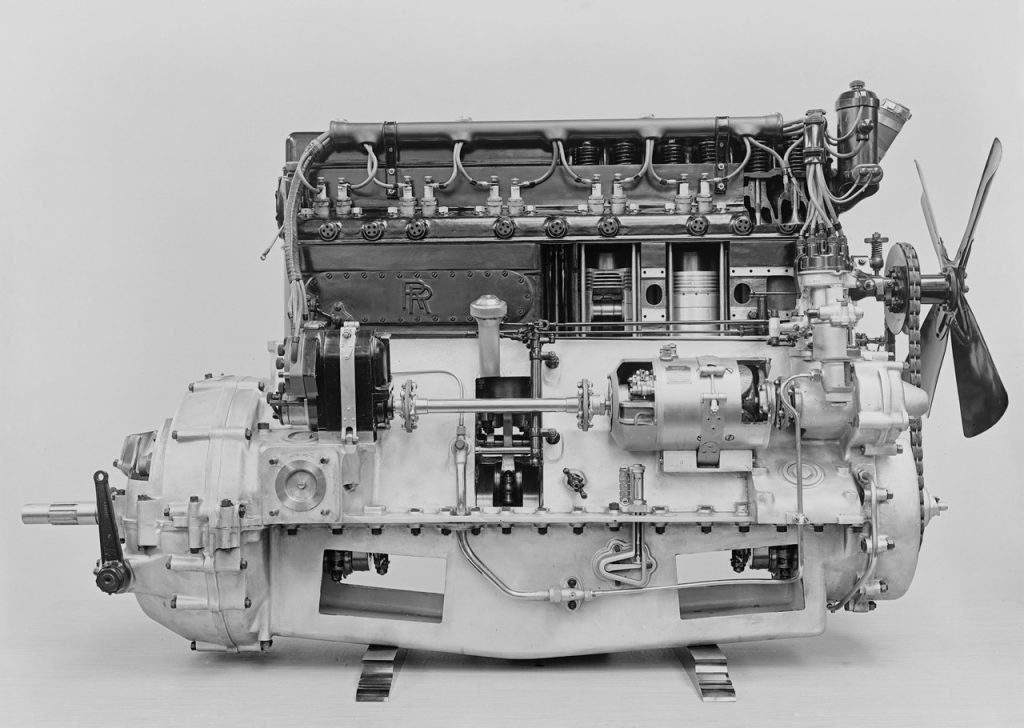

It was that A.G. Elliot–designed 7668cc long-stroke pushrod OHV engine, however, which was the main change, introducing a lot more power into the equation. Rolls-Royce had even considered a V12 for that first Phantom, as well as a straight-eight plus overhead-camshaft and supercharged engine designs. But no, a seven-bearing six it was to be, cast, like its predecessor, in two blocks of three cylinders. On top (at first) was a steadfast cast-iron head with the cylinders fed by a single carburettor of Rolls-Royce design and sparked with twin plugs using separate coil and magneto ignition systems.

It had been developed in secret with the misdirecting codename of Eastern Armoured Car (EAC), with Hives dropping off bits of real armour round the factory to maintain the pretence.

Conditions in Britain, however, were not good and about to get worse. In 1926, just one year after the introduction of the Phantom I, the first General Strike hit Britain and at Rolls-Royce, Claude Johnson, the man whose commercial sense, organisational skills, and humane management style had saved the company as a separate entity (he was known as the hyphen in Rolls-Royce), contracted pneumonia and died. With Rolls already dead and Royce infirm and living in France, Johnson was sorely missed.

Phantom I was far from the vanguard of technical merit at the time. While it’s main claim to fame was that pushrod engine design, a year after its introduction, Sunbeam introduced its 3-litre Super Sports, the first production car with a double-overhead-camshaft engine. Yet despite that, the first Phantom model was superbly engineered.

There’s an irresistible story about the car attributed to Maurice Olley, who had worked for Rolls-Royce’s US Springfield plant, but when it closed had gone to work for General Motors. In 1924, when “The General” opened its 4.5-mile speed loop in Milford, Michigan, not a single model tested could survive two full power laps without ruining its main bearings. Enter a Phantom I with a gargantuan, seven-seat landaulette body on top, which proceeded to gracefully perform lap after lap at its top speed of 80mph with no sense of jeopardy. Subsequently stripped and inspected, it spurred US carmakers to fit more robust bottom ends and bearings to their cars from then on.

Even so, it took the next Phantom II model before Rolls-Royce made catch-up with its rivals with improvements to the rear axle, gearbox, frame, and springing. With the Phantom I experience, Henry Royce had gradually caught on. As he wrote: “Now we all know it is easier to go on the old way, but I so fear disaster by being out dated and having a lot of stock left, and by the sales falling, by secrets leaking out, that I must refuse all responsibility for the fatal position unless these improvements in our chassis are arranged.”

Again, as ever, Royce was perfectly happy to take what he thought best and improve it. So, the Phantom I’s front brakes were based on a Hispano-Suiza design of alloy drums with iron liners, with a servo motor based on that of Louis Renault. Licences were paid…

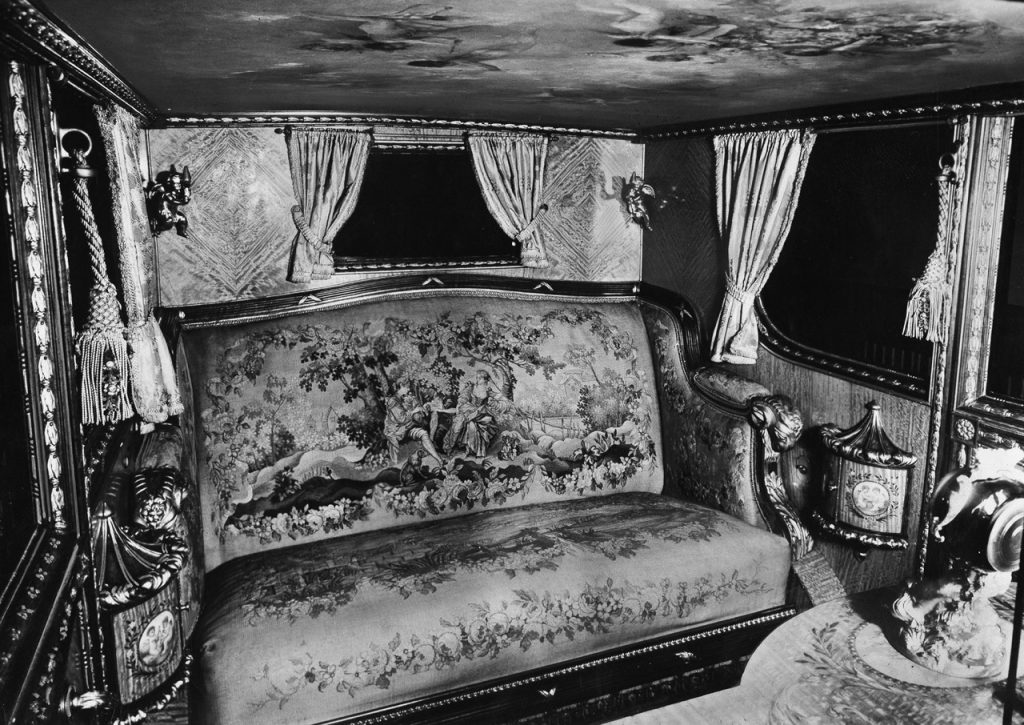

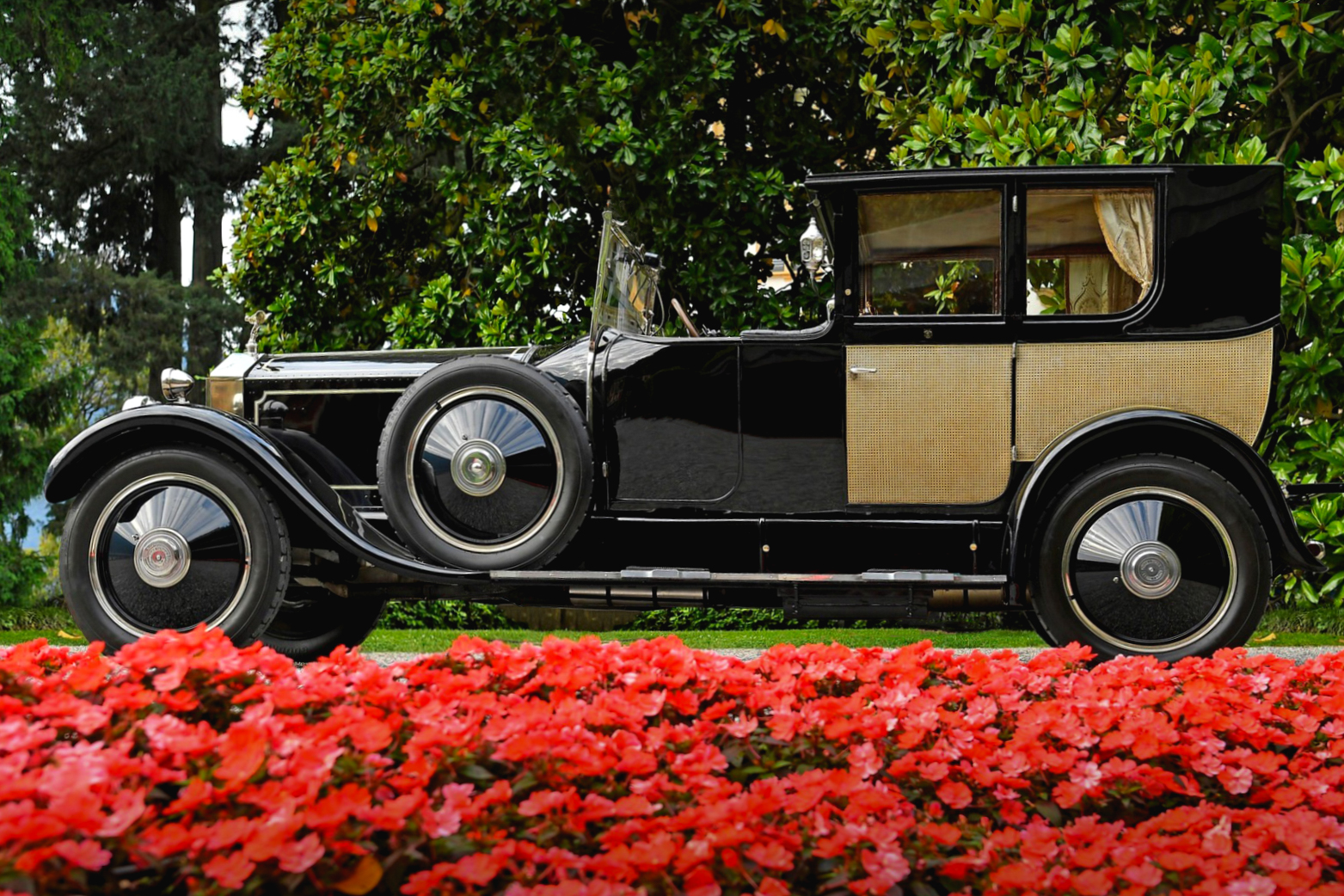

Of course, at this time you didn’t just walk into a Rolls-Royce showroom and drive out in a car. What you purchased was an order for a rolling chassis with a scuttle and Grecian column radiator, ready for your chosen coachbuilder to clothe in aluminium. It had ever been thus, though the Phantom I’s overhead-valve engine meant it was taller than the Silver Ghost’s side-valve unit, so bonnet heights would be higher and that increase in power (and braking) meant more sporting pretensions could be accommodated.

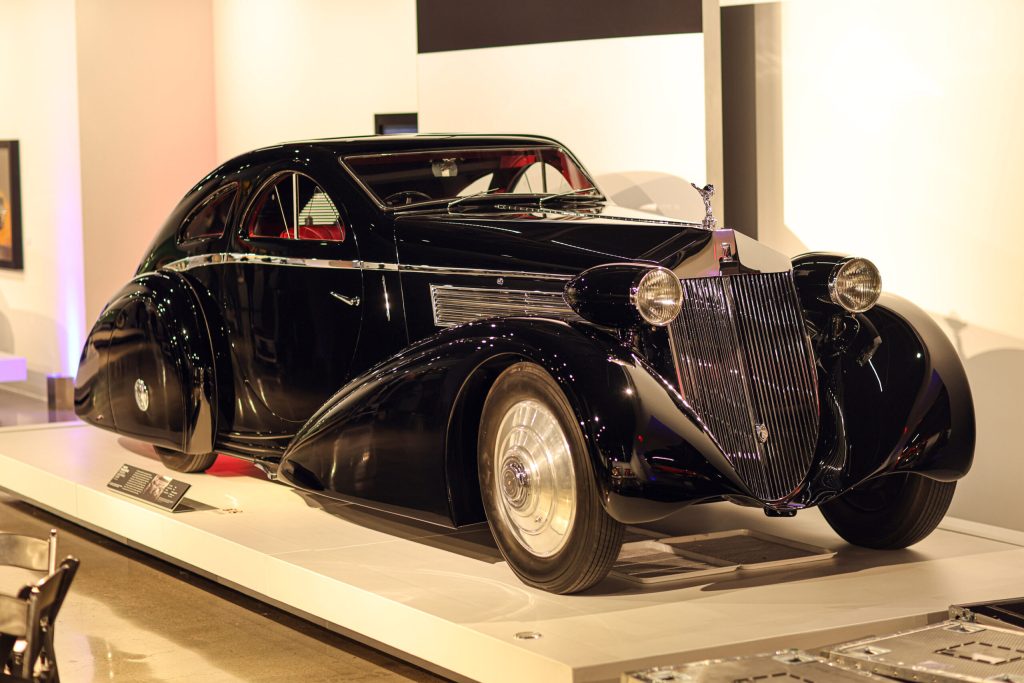

Those early cars tended to be straitlaced big saloons, open tourers with straight side panels and cycle wings, but the coachbuilding trade was becoming more adventurous. Barker and Butler did some stupefyingly beautiful bodies on Phantom I and subsequent models including a reverse sloping windscreen design on a Phantom III for Viscount Montgomery of Alamein. And just check out the Jonckheere Carrossiers of Belgium’s rebody on a 1925 Phantom I. It’s just a wild, wild coupe.

The difference in body styles and weight also meant that estimations of performance were difficult as aerodynamic drag, rolling resistance, and even engine power would differ between one body and another. Culshaw and Horrobin’s Complete Catalogue of British Cars lists the Phantom I’s 7668cc six as delivering a peak of 95bhp at 2750rpm, some 500rpm more than in the last Ghost models.

The chassis came with two choices of wheelbase – 12ft and 12ft 6in – which cost respectively £1850 or £1900 in 1925 – about £93,000 and £95,438 in today’s values. The springing was via half-elliptic leafs all round, and the wheels were a 21-inch Rolls-Royce centre-lock design. The track was 4ft 10in and the rolling chassis weighed 1811kg, without spare wheels and lamps. Culshaw and Horrobin give the top speed as 90mph and list the Phantom II as having 0–50mph acceleration in 14.5sec.

The Phantom name is, along with the 1935 Chevrolet Suburban, one of the longest surviving in the history of the automobile. Although the Phantom was introduced in 1925 and the Suburban in 1935, Rolls-Royce hasn’t always had a Phantom on its books, so you take your pick with these sorts of statistics. The Phantom I got upgrades during its production run, including an aluminium cylinder head, but in the end, Rolls-Royce had to make the chassis changes the car so badly needed, which begat the Phantom II and in 1929.

And the fate of these first machines was ignoble. Many ended up on farms pulling machinery, some had truck bodies attached and were used as beasts of burden, others became NAAFI (Navy, Army, and Air Force Institutes) wagons in World War Two.

Lord Montague found his father’s 1925 Phantom I gently rotting beside the playing fields of a school in Somerset, where it had been cut down to pull the gang mowers. At a time when commercial engines were more likely to be petrol as diesel, the big Rolls with its separate chassis and torquey engine was easy to convert, and so they did. And to buy they were dirt cheap. My mother went out with a young doctor training at The London in the 1950s who ran a Phantom and a Bentley Speed Six, and neither was worth more than 50 quid at the time.

Fortunately, these days they’re rather more valued by their owners for all their size and quirks. Like having an elderly elephant in the garage, a Phantom I is to be loved for what it is rather than what it isn’t.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading the Full English on the Phantom I and much appreciated the first photograph and the third one . We have had the car now for 55 years and have done 230,000 miles in it , initially in America from 1968 to 1974 when we came back to Britain.

Andrew you would be most welcome to come and drive it . Usk. NP151AT

On a new subject now, 40% of british households do not have a driveway or off street parking, EV’s for everyone? it is NEVER GOING TO HAPPEN. the sooner the powers that be realise that the sooner we will get Hydrogen to drive our cars etc there is NEVER going to be enough charging points or elec power to back it up