Just four bolts hold a Volkswagen Beetle engine in place. How do I know this? Because when I was on the spanners, we managed to get the Beetle engine-out time down to about 20 minutes; that’s from driving the car into the workshop to the flat-four motor resting on a castor trolley and the car jacked up at the rear like an up-tailed duck. More recently I went online and found that we were absolute amateurs in the speedy Veedub engine-out stakes, 72 seconds was the then-record, now it’s closer to 64 seconds. Take your pick, but be warned, this is a very deep rabbit hole and WD40, wingnuts and washers play a huge part.

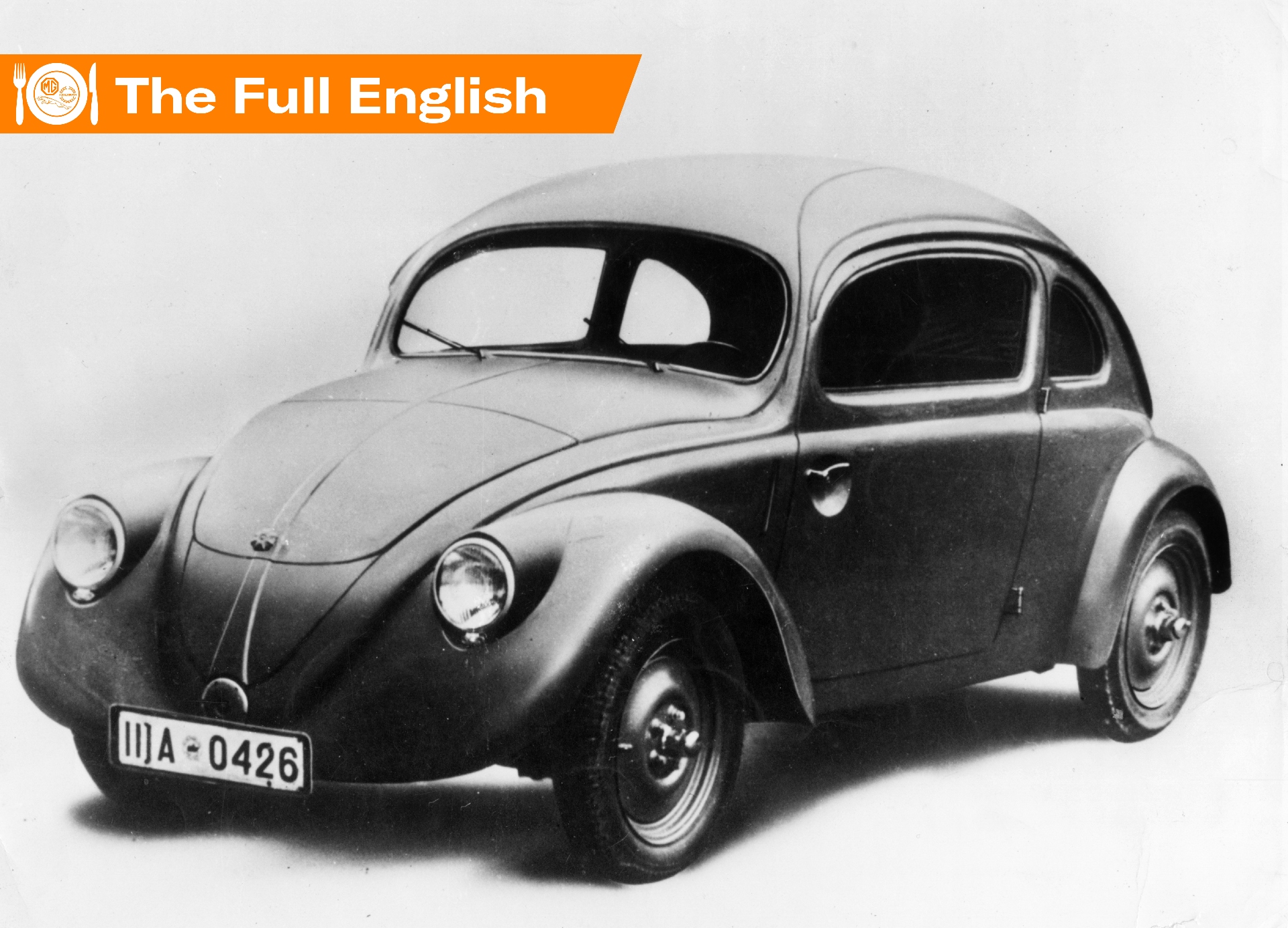

What a remarkable little car the Beetle is, though. Ordered by Adolf Hitler who was obsessed by motor cars, designed by Ferdinand Porsche, who half-inched a lot of the ideas and with a production run of over 21.5 million, the Beetle (or der Käfer in German) is one of the best-selling cars of all time. Pretenders to the crown include Toyota’s Corolla with over 50 million produced, Ford’s F-series pickup with over 41 million, VW’s Golf (35 million) and Passat (23 million) and Honda’s Civic (24 million), but these are name plates rather than the same models and in the case of the Ford, not actually a passenger car. For me, VW stands alone as the first people’s car and in Mexico, where the Beetle’s 65-year production run finally came to an end in 2003, they were called Belly Buttons because everyone had one.

Cheerful, reliable and relatively spacious transport, the Beetle’s genesis lies in dark and terrible times. Yet can we love the art in spite of the artist? Should we forever condemn the works of Pablo Picasso because of his views of women, the compositions of Richard Wagner because of the obsessional love the Nazis had for his music, should we never use the Gill sans typeface because of its compositor, Eric Gill and his abuse of his daughters? And how do we deal with the Beetle?

Certainly, it was born out of the National Socialists’ natural desire to create a German people’s car; cheap, dependable, utilitarian transport, which would be a result of cooperation of Germany’s leading car makers, who’d been hit hard in the depression of the 1930s. What’s wrong with that? My local swimming pool, a completely lovely 50-metre, open-air heated lido, was built in the Thirties out of similar patrician aims.

But right from the start, the project was dogged by controversy, not least the source of the ideas for its configuration and design, which was far from being uniquely that of the single minded and supremely talented Ferdinand Porsche. For all the could-have-been prototypes such as the 1932 Porsche 12, or the Type 32 prototype built for NSU, there stand the ideas of Béla Barény, the Hungarian engineer and car-safety pioneer, who managed to prove in court that Ferdinand had infringed his patented ideas. Or Hans Ledwinka, Tatra’s chief designer, whose ideas for back-bone chassis, rear-engines and swing axles were openly copied by Porsche, an act of plagiarism which was finally acknowledged in 1961 when Volkswagen was ordered to pay Tatra three million Deutsche Marks in damages.

In his book, Battle For The Beetle, author and historian Karl Ludvigsen also mentions the pioneering rear-engine designs of John Tjaarda. There were also the pioneering rear-mounted, flat-four, air-cooled engine prototypes and ideas of Jewish-German car designer Josef Ganz, who was arrested by the Gestapo in 1933 and forced to flee Germany in 1934, also the year Hitler handed Porsche the commission for a people’s car.

And then there was the way the project was morphed into the evil ideology of the Nazis, a people’s car to join the people’s wireless set and refrigerator – populist capitalism. There was even a Beetle share scheme, Sparkarte KdF-Wagen, where workers purchased stamps to be redeemed against the delivery of a new Beetle, though the agreement was never honoured and it took the stamp savers repeated court action to finally, in 1961, get VW to settle its account.

Hitler opened the 1934 Berlin Motor Show in military uniform calling for his new car. “I would like to see a German car mass-produced so it can be bought by anyone who can afford a motorcycle,” he squawked. “Simple, reliable, economical transportation is needed. We must have a real car for the German people – a Volkswagen!”

Indeed those names, Volkswagen “the people’s car company”, KdF wagen, or Kraft Durch Freude (Strength Through Joy car), all have a chilling ring when looked at from the other side of World War Two. And as L.J.K. Setright notes in his social history of the automobile Drive On!, Porsche took credit for the lot, though he also had his own car factory in Stuttgart.

Conceived by war criminals, financed by deception, designed through plagiarism, the little Beetle couldn’t have had a harder start in life, but that was all to change in April 1945 when Colonel Kennedy and his American forces marched into KdF city and stopped the looting of the factory and waited for the British, who had been given control of that administrative area. Major Ivan Hirst of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers stepped into the factory that August. I met him several times and what a charmingly modest man he was.

The rest as they say is history. The Allied plans called for 40,000 cars to be built in Germany to be used by the occupying forces and half of those cars were to be built in the British zone, and without a secure supply of bodies for the Ford Cologne plant, those cars had to come from what was rapidly renamed from the KdF factory to ‘Wolfsburg’.

Just 630 KdF cars were built during the war, since the plant had walled up the cars operation and concentrated on building 65,000 Kübel- and Schwimmwagens and munitions including the V1 and V2 rocket bombs. Sixty per cent of the factory had been destroyed, but Hirst and his men set to with VW engineers clearing unexploded bombs, rebuilding, and fulfilling the 20,000-car contract. When it came to handing back the factory to the Germans, there were a number of interested parties including the French, Ford, the Russians whose zone bordered the area, and believe it or not the Australians. Hirst and fortune favoured Heinrich Nordhoff, a forceful man who had been head of production at the highly advanced Opel factory. Privately wealthy, an engineering graduate and General Motors trained, Nordhoff became ‘Volkswagen’s first salesman”. He demanded absolute control and rebuilt the operation with his watchwords of quality and mass production to the fore.

In 1948 VW built 19,127 cars, in 1949 146,590, and in 1950 a new Beetle rolled off the line every two minutes and, according to Heinze Todtmann’s Kleiner Wagen Auf Grosser Fahrt (Small Car On A Long Journey), every month 430 rail wagons brought in sheet steel and casting parts, rubber paint and electrical components, 650 trucks brought in 10,000 tonnes of coke and coal from the Ruhr for power in the facilities which still exist today, though one of the four coal burners is a nightclub – and in July 1953 the half millionth Beetle was built.

It was that year that The Autocar tested a £439 VW Beetle pronouncing it “a roadworthy, robust small car bred for the autobahnen and in the Alps”. This 717kg, 24.5bhp/49lb ft, 1131cc flat-four car had a top speed of 62mph, with acceleration from 0-30mph in 7.9sec and an average fuel consumption of 37.7mpg. Mysteriously they also loved that wand-in-soup gear change quality, but reckoned it gave “good performance without effort, it is nicely finished, easy to maintain and backed by elaborate service facilities at fixed prices.” In short, they loved it as much as anyone else.

The Americans did too and in the 1960s the simplicity of the Beetle was a hit with the Flower Power generations (as well as the Type 2 or Microbus), with the greatest Beetle sales in the early part of the decade fuelled by some of the greatest advertising of the time including Doyle Dane Bernbach’s 5008 parts ad and The Volkswagen Theory Of Evolution.

I was there in a snowy Detroit in 1994 when Volkswagen reinvented the Beetle with the Concept 1 and watched as the hefty American press corps literally sprinted up three floors to the press room to file to an adoring American audience which thought it could remember the Sixties. Thing is though, interpretations vary, wildly. During lockdown there was an absolutely excruciating attempt by VW’s spin doctors to recreate Herbert Diess, VW Chairman as a kind of Elon Musk/Jay Leno/James Corden with a series of YouTube videos entitled Diess Speaks. In one he drives with the redoubtable Carl Hahn, former assistant to Nordhoff and VW chairman. He was 95 years old and still as spiky as ever – I interviewed him several times and he was a charming but tough interviewee and in today’s world of mainly pygmy leaders of car companies, an intellectual giant. Sadly he died last year. Anyway, Diess is trying to railroad him into talking about VW’s issues over replacing the Beetle in the States and Hahn is having none of it.

“It was very easy,” he says, “In my days, we were very popular in the States thanks to our advertising – the best advertising of the 20th century… We were so popular in America that the Beetle was known to families as the friend who sleeps in the garage…”.

Diess looks uncomfortable enough to be wondering about jumping out into moving traffic.

But my family loved the Beetle. Starting with my grandfather who drove one of Hirst’s early examples in occupied Germany after World War Two, to my mother who had several. I can vividly recall an image of my brother, crammed along with our huge black Labrador, into the rearmost luggage trough above the clattering air-cooled engine as we meandered our way to the Devon coast in my mother’s Beetle. There’s probably a law against transporting children and dogs like this nowadays, but neither Edward nor the dog complained or at least we didn’t hear them from that far back.

Back then Beetles weren’t the anachronistic classics they seem today, but respected and highly reliable family transport. Mum’s was a 1300, but it was later swapped for the 1600cc version with MacPherson strut suspension, which was sourced through the Beetle garage in Plumpton Green in West Sussex and seemed unimaginably cool with its big rear tail lamps and Blaupunkt radio in the metal dashboard.

Note that this was The Beetle garage, not The Variant garage, or the K70 or Type 4, or 411, or EA266 garage, or indeed a garage named after myriad highly forgettable and largely unsuccessful Beetle replacements, which VW foisted on the public in the 1960s and Seventies. By 1971 and its test of the Super Beetle, Motor magazine started the test with: “Volkswagen has established something of a reputation for being the great escape artist of the motor industry. Just when it seems time is at last about to catch up with the Beetle, Wolfsburg pull another trick out of the hat…”.

Thankfully we’d just have three years to wait for the long overdue Golf replacement in 1974; it might have been a remarkable run, but Beetle had definitely run its course.

These days, the Beetle is as simple and robust classic as you could ever want. I recently saw a rather tempting 1970 1500 model in brilliant condition for £11,000, which could quite easily be a daily driver. Parts supply is fantastic and there are plenty of cars out there to suit every pocket and maintenance abilities, even if you don’t fancy removing the engine in 64 seconds.

I’m still not sure how this extraordinary car captured hearts quite like it did, but I’m sort of glad it did, even if that clattering engine and metal dashboard bring back memories of family holidays and endless runs to the sun.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage for daily news, features, interviews and buying guides, or better still, bookmark it.

The worst car ever built. Awful engine Inthe wrong place, very little luggage space, terrible to drive, only two doors, noisy slow and handled like a barge.

A nice little article. However the author should know their Bought from Brought!! Does anyone proof read?!

Forget about the car, let’s talk about the writing. Excellent

I’ve run one since the 70s and still going

Not a car that I wish to own but a car that I do respect and admire.

+1