Donald Healey is a figure of immense standing in the history of British sports cars. Easily as famous as William Lyons, Cecil Kimber, or Colin Chapman – Messrs Jaguar, MG, and Lotus, respectively. So it’s mildly shocking to hear him described as “a bit of a chancer” and “probably the most successful British car manufacturer who never built a car.” And that’s from someone who won’t mind me saying is one of his biggest fans.

Then again, Warren Kennedy knows the original Healey cars better than anybody. We stand for a few minutes flicking through a recent book on the Healey marque. Kennedy has been in, under, or around almost every example lavishly pictured in his capacity as one of the UK’s preeminent classic car restorers. It’s a shame the author didn’t consult him first, because the book is peppered with errors. Kennedy owns Donald Healey’s original pocket notebooks and also the company’s early ‘Experimental Files’ archive. He knows that only by careful study can you nail the truth.

“I now know there was poetic licence in everything Donald ever wrote,” Kennedy says, although not with any vitriol. “I’m sorry to say it but you can’t believe a lot of what appeared in the Healey books; the ‘X Files’ constantly contradict what Donald said in public.”

Kennedy has uncovered countless mix-ups and obfuscations over chassis numbers, race modifications, and customer deliveries. There’s nothing too heinous or scandalous; mostly it’s just anomalies in the frantic struggle to start a car company from scratch, and the nimble duckings and divings of a typical entrepreneur.

Kennedy, indeed, is actually full of admiration: “Just look at what he did; by December 1945, he’d produced a whole car in a period when you couldn’t get any materials. Within a couple of years Healey cars were winning races and rallies and were in production, but they were more expensive to make than an Aston Martin, so Donald couldn’t afford to waste anything . . .”

Donald Healey’s background in the 1930s as a racing driver and then technical director of Triumph is well documented. As are his secret WWII manoeuvres to start his own car company. Quite a bit less well-known is how he financed it; he found most of the £50,000 seed capital from a keen young fellow from Cumbria called James ‘Jimmie’ Watt. Watt’s wife Rachel had lost both her parents by the age of 13, and a few years later she inherited a substantial estate. A lot of that was poured into the Donald Healey Motor Company, and Watt became sales director. Once again, you’d never know it from the books written by Donald and Geoffrey Healey, where James Watt is accorded the importance of an office tea boy.

Two other characters have been almost airbrushed out of Healey history, too, and Kennedy feels their contribution ought to be acknowledged.

“It was Bill Buckingham, along with his brother Ray, who built the body of the prototype Healey 2.4, chassis A1501. They were panel beaters at the Buckingham Sheet Metal Works at The Chase, Leamington Spa. Donald would only have had a sketch and Bill Buckingham would have told him how they’d need to do to build it. I know this from my own panel beaters: You have to listen to them no matter what, because they know all the issues!

“Only when the prototype was sent to Westland Motor Co, the coachbuilders in Hereford, would it have been ‘productionised’, and all the patterns made.” In fact, the manufacturing work was mostly outsourced as there was only room for five or six cars at Donald Healey’s ‘factory’ in Warwick, which was really more of a race shop and a delivery point for accepting the Riley engines, gearboxes, and back axles. “Donald was a kit car builder, really: Westland did most of the assembly,” Kennedy chuckles.

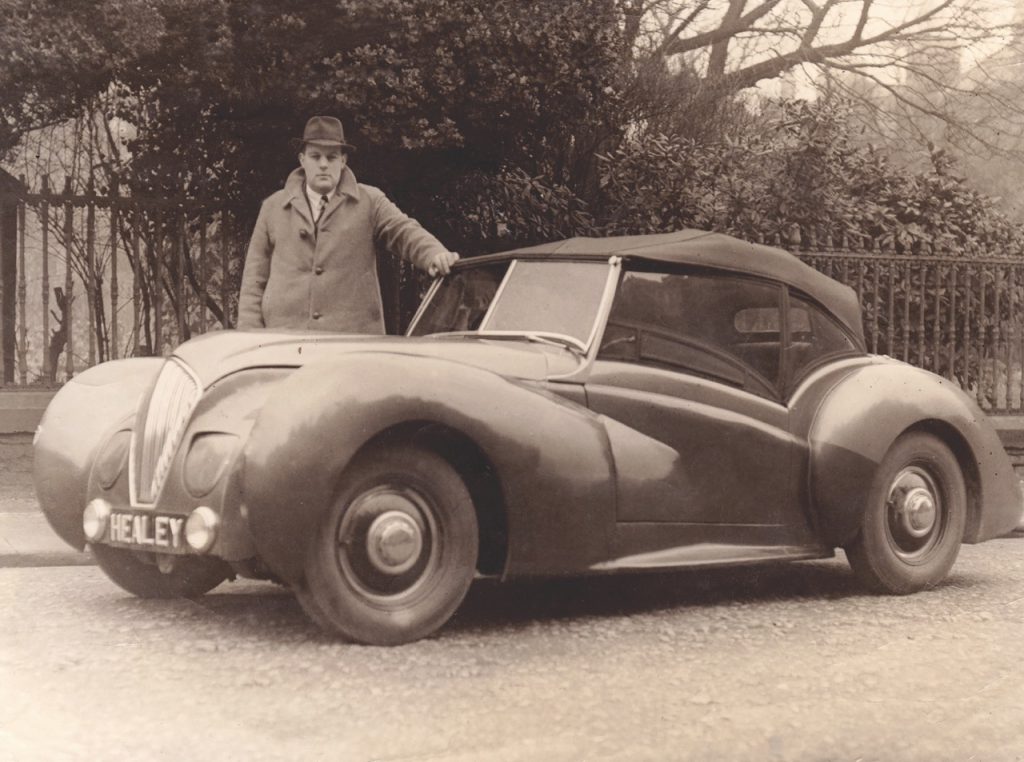

Healey’s prototype was completed by 10 January 1946, Kennedy has deduced, and spent much of its first few weeks in existence being hammered around local airfields to iron out faults. Healey and Watt nicknamed it “The Horror” because every time it returned to company HQ it needed more welding to hold it together. “They made the chassis out of too thin a gauge steel because Healey wanted the car to weigh less than a ton,” Kennedy explains. “The whole thing flexed and fractured.”

With all its shortcomings, A1501 led a short and brutal life. It was soon replaced by A1502, a version that hit a headline-getting 111mph in Belgium to become the world’s fastest production saloon car, and A1503, another tourer with GWD 43 registration number, which was used by Donald Healey to compete in the 1948 Mille Miglia. The Healey marque was on its way. Within a few short years, its Silverstone sports car and luxurious Nash-Healey made it world-famous, and then it teamed up with BMC to produce the first Austin-Healey in 1952.

But a little more about my host today . . .

Starting in 1978, Warren Kennedy served his apprenticeship with Ogle Design, part of the build team on the Range Rover Popemobiles. Within a few years his own Classic Restorations became a leading MG restoration business, and he confesses to never even hearing of a Healey 2.4 until a friend bought one and asked him to sort it out. It opened up a new world for Kennedy. Because of the early Healey’s Mille Miglia eligibility, Kennedy has driven nine of the events himself in his customers’ cars, and even sponsored the event under “The Healey Collection” banner. “I’ve actually taken all the works cars that Donald drove on the Mille Miglia back to Italy,” he tells me.

His Northamptonshire workshop has become a Healey hotspot, and many of the rarest and most important 2.4-litre cars – either to own or rejuvenate – have come his way.

And that’s why I’m here: to see the car that started it all. I must declare a remote interest myself. Although I never knew him (because he died in 1966, when I was less than a year old) Jimmie Watt was my cousin, and I’ve always been fascinated by his Healey escapades. As well as driving The Horror back home to Carlisle, he also once drove a Healey chassis from Warwick to Turin, Italy – with no bodywork whatsoever and wearing a white flying suit and goggles. Kennedy’s premises are as close as I’ve ever come to the authentic atmosphere of cousin James.

And Kennedy has made some extraordinary discoveries.

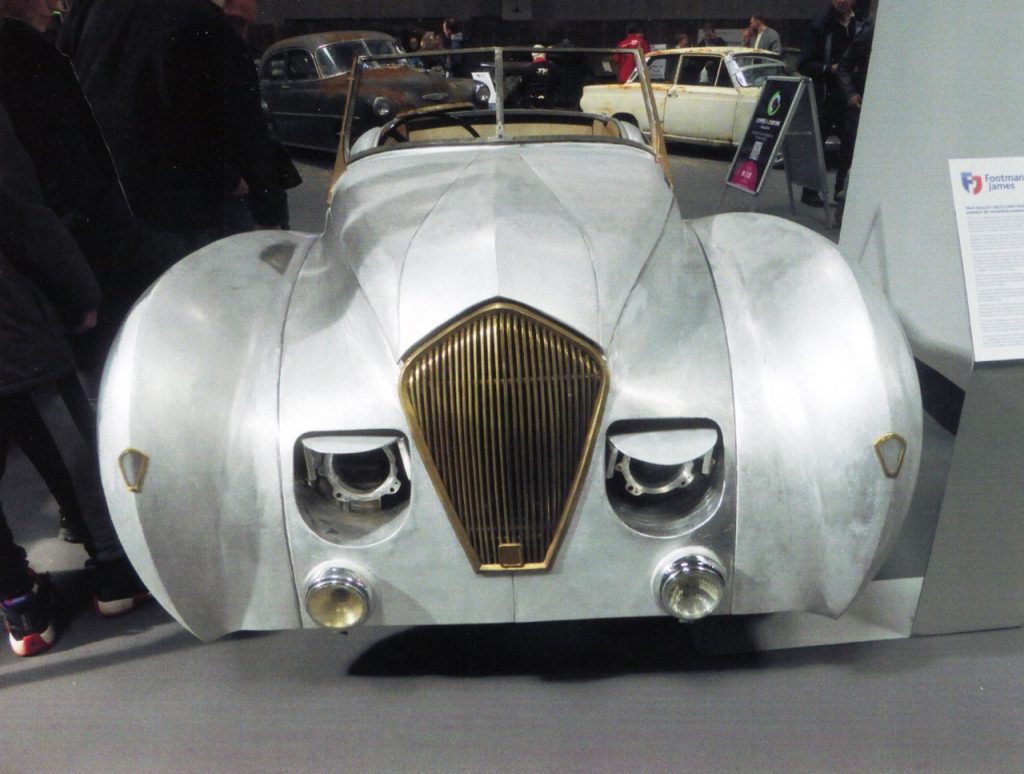

He was beginning to restore that illustrious third car built, A1503, when his intimate familiarity with these Westland tourers triggered an alarm bell. The bonnet was hinged at the front (not at the back as it should be), the bulkhead was in an odd position, and the wings were a little too peaky in profile. Why was the hood frame different? What were these strange extra timbers? Why the wrong sidelights?

“I thought, someone’s really messed around with this, and then I noticed it had a shorter boot and a fold-down panel for the spare wheel,” Kennedy recalls. “I knew it wasn’t right, so I took the body off and made an entirely new body, from scratch, new ash frame, the lot.”

The old body went into one of Warren’s numerous dry stores with all his other Healey spares. A bit like Donald himself, he never throws anything away that might have some use.

Later on, Kennedy won an ugly two-seater called a Duncan Drone at a Bonhams auction. The Drone was a sports car whose design was cooked up by James Watt and coachbuilder Ian Duncan and was little more than a tax dodge; the super-basic body on the Healey 2.4-litre chassis could be bought for less than £1000 all-in, which brought the car in at under the punishing Purchase Tax rate at the time of 66 per cent. The sneaky ruse was that an owner could discard the body and then order a pukka one, saving a small fortune in the process. In some hands, though, the Drone took on an exciting life of its own. American James Cohen took his on the Mille Miglia and was doing magnificently until 112 miles into the race it barrel-rolled in a crash and killed his co-driver (the guilt about that most likely caused Cohen’s suicide a few weeks afterwards, and Warren owns that car too).

As Warren was removing the Drone’s body, another startling thing was revealed. With the help of some gentle sandblasting and advice from forensic metallurgist Michael Trott, he found chassis number B1938 had been stamped over . . . A1501.

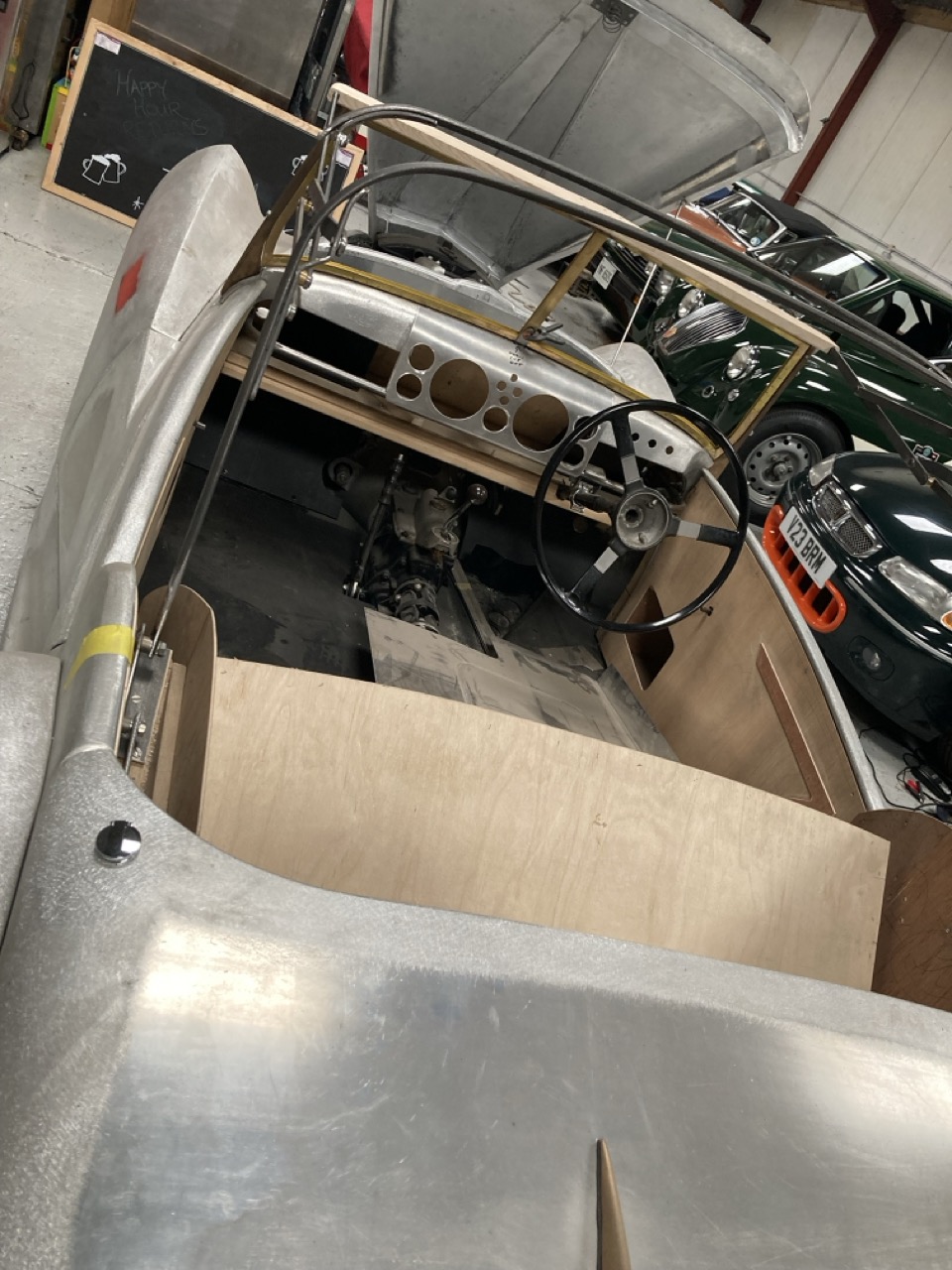

“The minute I took the body off I realised what we’d got there. They’d taken the body off A1501 and put it on GWD 43. Every repair that Geoffrey Healey did in 1946 is still there, we haven’t removed any of them. So we got the old ash frame out of our store, dopped it on the chassis, and all the holes aligned perfectly. It was an unbelievable moment. The very first car was back together.”

The discarded and unwanted chassis, meanwhile, had been given to my late cousin Jim in 1948, who had it turned into a Drone of his own. Somehow he managed to squeeze his 6ft 2in, 19-stone bulk into its tiny cockpit and finally possess a Healey of his own to hare about in.

Kennedy’s reuniting of the two halves of the first ever Healey – found by chance inside two other cars – is by no means the end of the story. In fact, for Kennedy, the end is not even in sight. He’s decided to make it his mission to return A1501 to the exact spec Donald Healey and his team originally planned. So much was changed from the original design; not just the decision to go for a rear-hinged bonnet, with the batteries under the back seat, but also the headlights.

You see, Healey’s design included headlights hidden behind retractable covers for an ultra-sleek look, inspired by one of the most exciting cars of the late 1930s, the Cord 810. They were depicted in the early brochure to get customers excited, and fitted to The Horror, but as the little company battled to get its new car into production, the vacuum-operated mechanism proved too difficult to finesse.

“They had to start cost-cutting, really, and so reverted to normal headlamps. It’s a very strange car in many ways. Donald was clever in saving money – the steering box is from a dumper truck, and because he wanted this to be the first car with 15-inch wheels, so are they. But then he couldn’t find a hubcap to fit, so made his own, which needed 12 pressing tools to make and needed their own balancers, and so they’re the most expensive ever designed!”

Kennedy has reinstated the headlamp flaps and built his own rod-and-cam system to operate them – clunky but effective. “It took me a long time to make them work,” he sighs. Now his focus has gone to the back of the car. “Even the spare wheel hatch wasn’t on the original but was added some time later. I’ve spent years looking for a rear-end photograph of this car, and eventually I discovered that the spare wheel hatch and pull-out tray were not original features but done by two brothers who owned the car in the late 1950s. Not by Healey at all. So now my dilemma is, do I change the back end to put it back to original, or do I leave it like this because it was done early in its life. For me it’s a difficult one.”

When I say it looks fantastic as it is and he’d be bonkers to remake the back end to get rid of a very neat feature, Kennedy doesn’t brighten very much.

“Hmm, well, it could go into the paint-shop tomorrow, it’s that close, but I have to make my mind up. The truth is, I don’t know what I’m going to do with this when it’s finished. I’m 62 and I’ve got 30 cars in my collection, and I can’t keep them all . . .”

Talking to Warren Kennedy has got me closer to my energetic, erstwhile cousin than I’ve ever been, and before I leave I feel closer still: In Kennedy’s office is the boardroom table and chairs from the Donald Healey Motor Company, where they all sat through the early years of crisis-management and confusion that gave us one of the greatest names in British sports cars. What a story to be a tiny part of, eh, Jimmie?