In case you were unsure whether a car can turn into a plane, we refer you to assassin Scaramanga’s escape in a flying 1974 AMC Matador in the classic Bond flick The Man With The Golden Gun. Fans of the 24 Hours of Lemons budget racing series in the US will know about the zany “Spirit of Lemons” build – the body of a Cessna grafted onto the chassis of a 1980s Toyota Space Cruiser van. However, we are aware of only one instance of a plane that was turned into a car, only to then turn back into a plane. For those knowledgeable about both planes and cars, it will come as no surprise that this is a story about Bristols.

Even British car enthusiasts might only be somewhat aware of Bristol as an automotive manufacturer, as it was always a low-volume producer. What was technically the company’s first car arrived between the wars, but the Bristol Monocar was more a motorcycle than a proper automobile. After the war, however, Bristol built relatively quick and luxurious cars aimed at the well-heeled set.

The parent company of Bristol Cars was the Bristol Aeroplane Company and, in aviation circles at least, it is much better known. Bristol’s aviation efforts include some of the most important British aircraft to fight in WWII – fighters and bombers that were arguably as important to the war effort as the Hawker Hurricane and the Spitfire.

Of particular note is the twin-engined Bristol Blenheim, the backbone of the RAF’s bomber force. It was just fast enough to serve as a night fighter above England, protecting her cities and factories from the Luftwaffe’s aerial Blitzkrieg. First flown in 1935 as the type 142, the Blenheim proved faster than any fighter aircraft currently in the RAF at the time. This performance spun the props at the UK’s Air Ministry, which promptly ordered 150 of the aircraft. In total, 4400 Blenheims would take to the air. Only one still does.

Before we get to that extant aircraft, first we must witness the service of Bristol Blenheim Mk 1 L6739, which entered the RAF fleet on the second of September 1939, the day after WWII began. It was assigned to No. 23 Squadron: the Night Fighters.

With the fitment of four Browning .303 machine guns in a gun pod, L6739 was upgraded to a Blenheim IF. Despite having the necessary firepower to shred a Heinkel into hamburger, these early Blenheims were not a complete success as night fighters. Twin radial engines produced over 800bhp each, but even this just barely gave the Blenheim the speed to catch the Luftwaffe’s bombers. L6739 fought hard but retired in 1940 after a little over a year’s service as the speedier DeHavilland Mosquito entered the fray.

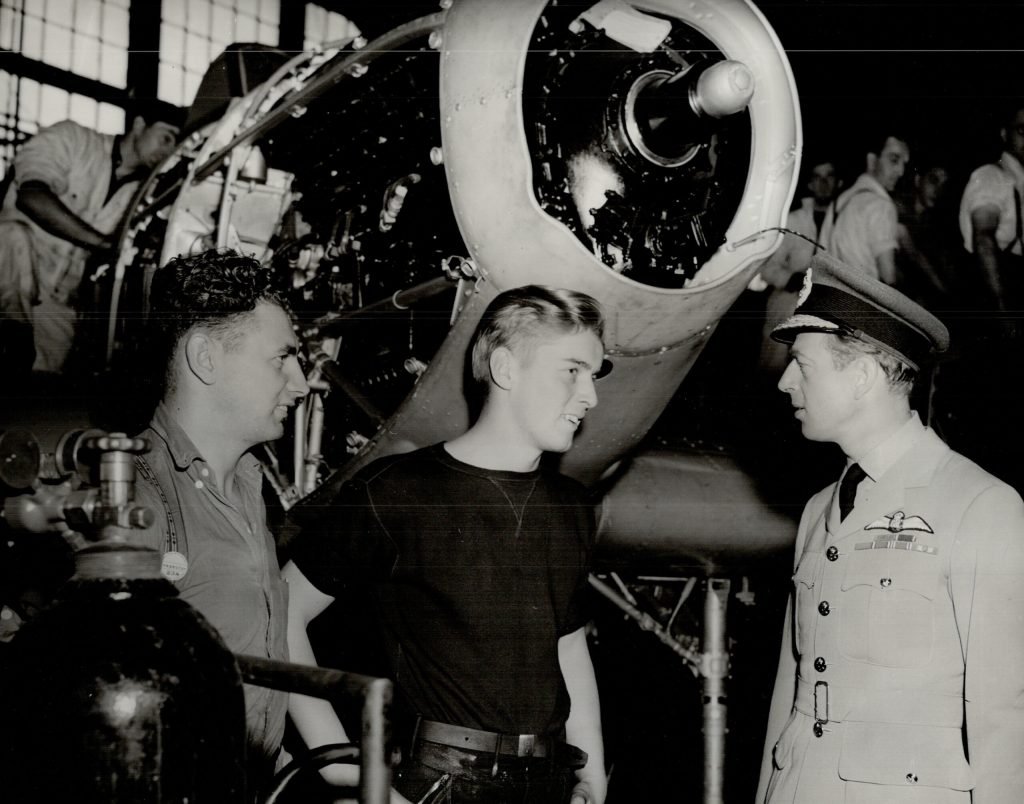

Sent back to Bristol, the airframe sat in the scrapyard as surplus. Nothing had been done to it by the time the war ended, at which point there were, of course, plenty of aircraft lying around all over the place. Seeing as it was just sitting there, a Bristol employee named Ralph Nelson decided he would build something out of it.

Nelson was a Class A example of what can only be described as “British Man With Shed.” This scrappy species (homo shedien) is responsible for everything from the founding of Lotus to the creation of the 27-litre Merlin-engined Beast that sold recently at auction. Brits can be inveterate tinkerers and inventors, occasionally of the Jurassic Park “so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should” variety.

Nelson took the short-nosed front cabin of the Blenheim, notorious for being hard to climb in and out of, and placed it on the chassis of an old Austin 7 he had lying around. He built a rear-hinged driver’s door for it, folded the rest of the sheetmetal into an egg-like profile, and then – to make things even weirder – he fitted an electric motor of his own creation as a motive unit. Then he road registered it as a “Nelson” with the number plate JAD347.

This homemade #car is #quirky even by our standards We know nothing about it but assume from the number plate that it was #UK registered from the #1940s/#1950s The front looks like it's from an #aircraft pic.twitter.com/QLo55b57kc

— Quirky Rides (@QuirkyRides) October 22, 2020

Nelson drove his eponymous aeroplane-based EV for around a decade, getting one of the UK’s windscreen-mounted tax discs each year. However, sometime in the mid-1950s, the car suffered a small fire that fatally damaged its running gear. He never got around to repairing it.

***

This brings us to a second Blenheim, or, more properly, the Canadian-made copy known as the Bolingbroke. G-BPIV entered service in 1943, flew for three years, and then was put out to pasture after the war ended.

Canada’s contributions to the Allied war effort, particularly as part of the UK Commonwealth, extended to more than troops. As previously covered, Canadian factories built many of the Hawker Hurricanes that fought against Messerchmitts diving out of the sun, and the Canucks also built most of the heavy trucks that replaced the materiel lost by the British Army at Dunkirk.

Allied bomber aircrew training was also a huge part of the Canadian effort, and inadvertently led to the rise of many postwar sports car racing clubs. In many cases, the airfields built for training had to be constructed quickly, so there wasn’t time for proper surveys of wind conditions. Runways were thus often built in overlapping triangles, and when they sat disused after the war, they were the perfect arena for amateur circuit racing. It’s why the Gimli Glider nearly crash-landed on top of an autocross.

The Canadian-made Blenheim was shipped to Scotland in the mid 1980s, where it was put in a museum collection. Later, it was sent to an aircraft restoration company near Cambridge, where it was completed in the style of a later, long-nosed Blenheim Mk IV. It took its maiden flight in 1993.

However, in 2003, it crashed after a demonstration flight and was damaged well beyond airworthiness. A huge restoration effort was mounted (some 25,000 volunteer hours) and the decision was made to try to show the Blenheim as it was in its earliest fighting days. The only question was where to procure a correct short-nose cockpit.

As it turns out, Ralph Nelson had heard of the original 1990s restoration programme and donated his car to the cause. Being an ex-Bristol man, he had taken great pains to preserve all the original control gear during the conversion to car, so the restoration team had very nearly a full set of everything they needed. They set to work.

At the End of the War Bristol Aircraft Factory worker Ralph Nelson used this Mk1 Blenheim cockpit to make an electric car that he drove around the City for 10 years.

— Tony Brown (@agbdrilling) February 15, 2019

It is now the cockpit of the restored and only flying MK1 Blenheim 🇬🇧 pic.twitter.com/PFa46lluWK

Bristol, as a car company, first brought elements of BMW back to the UK as part of postwar reparations, with the 400 even having a twist on the BMW twin-kidney grille. Later came Chrysler-sourced V8s and luxurious but muscular GTs in the same general vein as the Jensen Interceptor. The Bristol 603 of the late 1970s was called the Blenheim, in a nod to its aviation heritage, and another Bristol Blenheim coupe emerged in the 1990s.

There is also a plan to bring back the Bristol marque as (of course) a manufacturer of luxury EVs. While details are thin, the plan is for a four-seater battery-electric car to be announced in 2025. Given the work of Ralph Nelson, such a vehicle wouldn’t be entirely out of character for the brand.

But for now, should you see L6739 at its home base in Duxford, Cambridgeshire, or perhaps on display at the Goodwood Revival, where it has won several prizes over the years, look closely to see an unusual detail. Not only is this the lone airworthy Bristol Blenheim left in the world, but also, in tribute to Ralph Nelson, it is also the only one to display a UK road-tax disc in its window.

What a fantastic story, you just couldn’t make it up! Very well written too.

Seen at Duxford, a sign: “Happiness is a pair of Bristols”

I have a T-shirt with a strategically placed pair of round engines and the legend, “Happiness is big Bristols”. They were sold to support the charity.

You didn’t mention the Bristol Freighter in the potted history of the marque. Truly a coming together of aviation and automobiles, as operated by Silver City Airways across the channel.