The announcement that John Cena has signed on to be the star of the new Matchbox live-action movie raises a few questions. First – there’s going to be a Matchbox movie? And second – what will it be about, exactly?

We know that Cena is a car guy of broad tastes: He owns a couple of classic muscle cars but daily-drives a Civic Type-R, and he’s of course part of the Fast and Furiousfranchise of films. He’s also the kind of charismatic lead that doesn’t mind a bit of fun at his own expense. (His comedic timing probably comes from his days as a professional wrestler.)

What’s going to be in the script that gets handed to him?

With 2023’s Barbie hitting more than £1.1 billion in worldwide box offices, you just know Mattel is looking over its various intellectual properties and imagining a Scrooge McDuck–sized swimming pool of cash. There’ll be a Hot Wheels movie at some point, and since that franchise already has spawned multiple video games, it’s easy to imagine some kind of film with action-packed racing and huge stunts is in the offing, like a G-rated version of the aforementioned Fast and Furious. Matchbox is different, though, with quintessentially British roots and a less wildly creative nature than Hot Wheels, its corporate sibling.

What Hollywood should do, but probably won’t, is tell the real story of Matchbox, because it’s the tale of the rise and fall of the greatest toy-car empire in the world. It’s a story of postwar resilience, of a company holding out against hard times and fighting off market change. There are plucky East End Londoners getting away with schemes on the side, a public-transit system sponsored by a toy-car factory, and, at the heart of things, a skilled and slightly rebellious engineer.

Here’s the real story of how Matchbox grew to become the largest toy-car maker in the world, yet ended up being owned by its old rival, Mattel.

Before Matchbox: The Rebel and The Rifleman

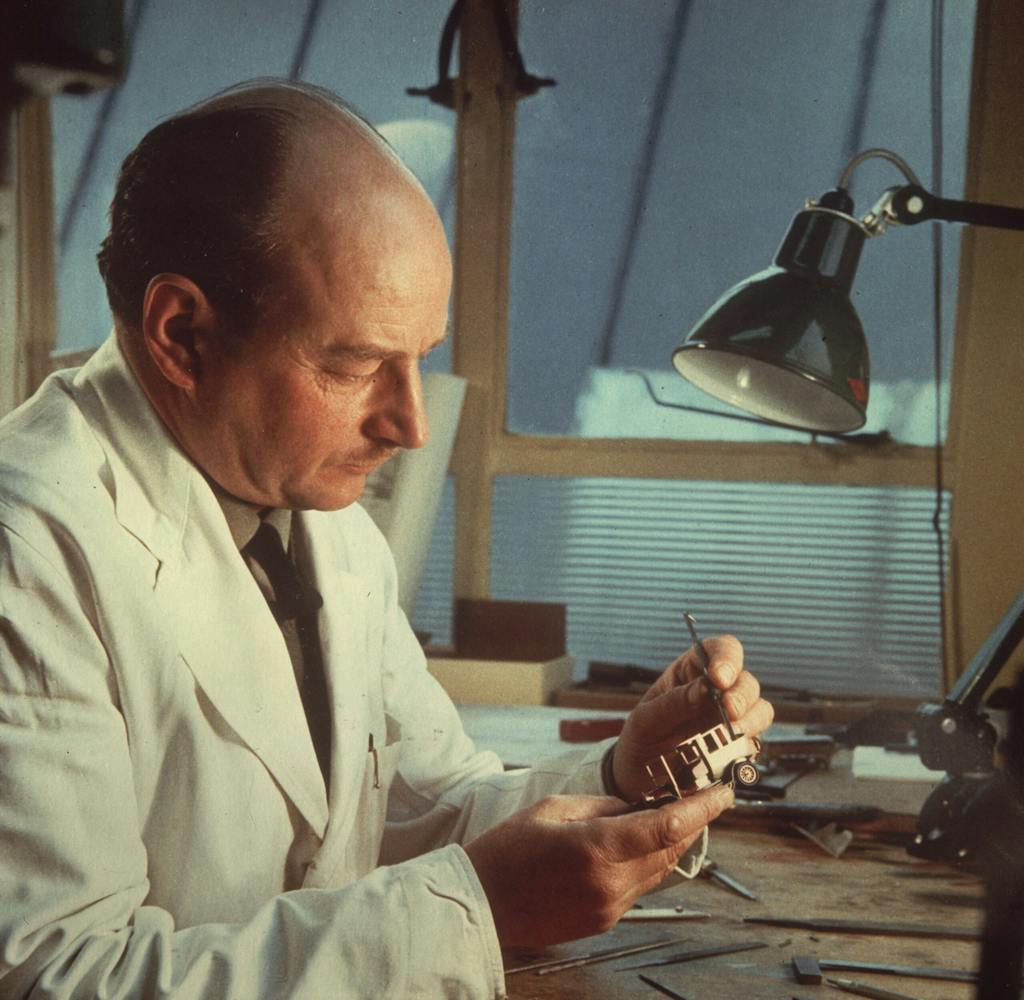

Born in 1920 in North London to a family of little means, John William Odell was kicked out of school at age thirteen for what he claimed was a rebellious attitude. He drifted from menial job to menial job throughout the rest of the 1930s before joining the British Army at the outbreak of the Second World War. He served in the Middle East and in Italy, eventually attaining the rank of sergeant in the Royal Army Service Corps, where he was responsible for maintaining fighting vehicles.

On the side, Odell built up a cache of parts for Primus portable stoves and ran a repair store to earn some spare cash. By the end of the war, he’d saved a few hundred pounds sterling, enough to get married and start a family. He got a job in London pushing a broom at a small die-casting firm. As he swept, he noted the relatively poor quality of the company’s products. With his years of experience mending tanks and supply trucks, he figured he could do better.

At the same time, fellow veterans Leslie Smith and Rodney Smith (no relation) had founded their own die-casting business in North London. Rodney had worked for the same die-casting company as Odell was. The two connected, and by pooling resources with Leslie, they registered Lesney Products Ltd on 19 January 1947. They rented a defunct pub called The Rifleman, which had been damaged by bombs during the war, and set to work.

Odell, meanwhile, had bought his own die-casting tools and then faced eviction for pouring molten metal at home. Needing a place to work, he joined the Smiths, and each person naturally found an area of the business that suited them. Jack made the tooling, Rodney the die-cast pieces, and Leslie ran accounts and sales.

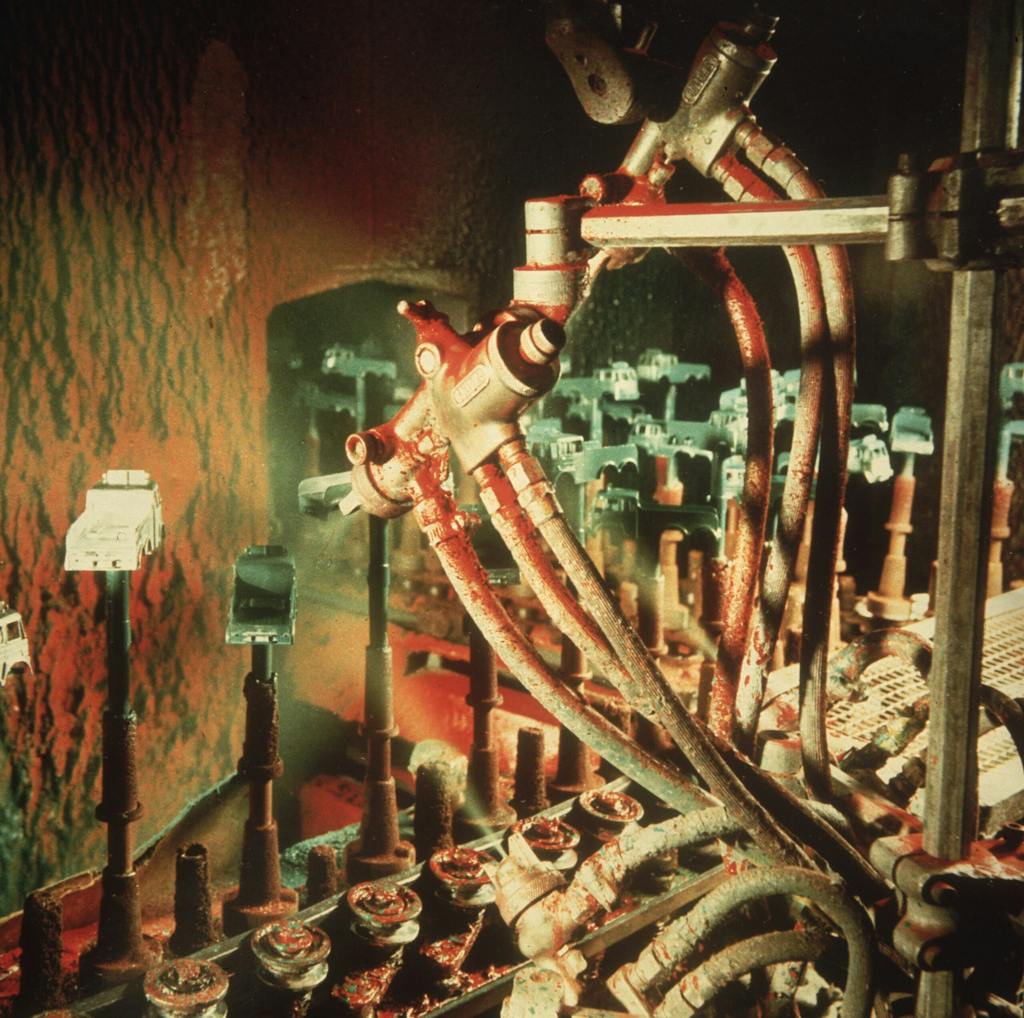

For the first year, Lesney made all kinds of household products, plus bits and bobs for the automotive industry, ceiling hooks, and other miscellanea. Business was steady, then began to tail off as Chistmas 1947 approached. Why not make a small run of toys? Dinky, the die-cast toy arm of building-set maker Meccano, made a model road-roller, so Lesney bought one and, thanks to Odell, improved upon the design using more die-cast elements. The Lesney road-roller toy was more robust, cost a third as much as the Dinky, and could be sold at any shop; Dinky and Meccano were only sold at authorised retailers. It was the first step.

Matchbox Is Born: The Queen and the Spiders

To this day, die-cast manufacturing of toy cars uses an alloy metal called Zamak (also known as Zamac or Mazak) that is almost entirely zinc. When the Korean War broke out in 1950, the UK government banned the production of zinc-based toys, fearing that reserves of the metal might prove crucial for the war effort. It was a disaster for Lesney.

Rodney, convinced that the end had arrived, sold his shares to Jack and Leslie, and went into farming. (Later, he’d return to the die-cast industry, working for one of Matchbox’s smaller competitors.) Despite having just two at the helm, Lesney managed to weather the hard times because it had quite a lot of zinc on hand. The company couldn’t build toys, true, but it could make automotive parts while others were struggling for the necessary raw materials. The decision helped the company bridge the gap until the war ended and restrictions were eased.

In 1952, King George VI died. Luckily for Lesney, Odell had already put together a very elegant model of the royal carriage, intending to sell it on the coattails of the 1951 Festival of Britain. They pulled the mould out of mothballs, modified it by basically sawing the figure of the king off at the knees so that only a queen rode alone, and released the model to the public. Available in two sizes, the smaller of them sold over a million copies, not just as a toy, but as a decoration for coronation celebrations all over the UK.

Flush with cash, Lesney was primed for the innovation that would set it on the path to greatness. Here we must introduce the young and mischevious Annie Odell, as much of a rebel as her father ever was.

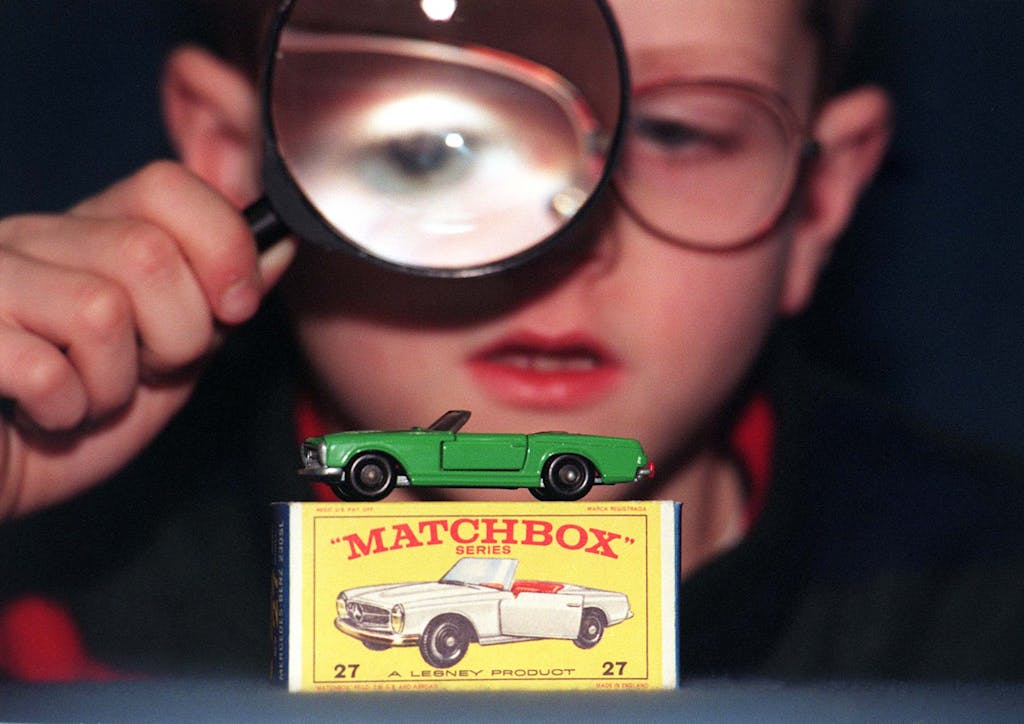

The oft-repeated story is that Matchbox got its name because Annie’s school only allowed children to bring toys small enough to fit into a matchbox. According to Odell himself, Annie had a habit of catching spiders and other creepy-crawlies, putting them in matchboxes, and then springing them on classmates and family members. By way of a bribe, he made her a scaled-down version of that original road-roller in 1952, sized to fit in a matchbox.

When put into shops just before Christmas of 1952, the mass-produced Matchbox models were not an overnight success. Their low price was a double-edged sword – they were accessible but not quite special enough to be the main-event Christmas present. After the holiday, however, as kids came into the shops with their pockets jangling with coins, the models fairly flew off the shelves.

Matchbox Reigns: One Hundred Million Little Cars

By 1967, Lesney sprawled across much of Hackney in London’s East End, outbuilding after outbuilding huddled around a huge factory made of concrete. It employed several thousand workers, most of them women. The size of the Lesney workforce and its location meant that there were a few cheeky liberties taken here and there. The children of Hackney were never without a few Matchbox toys that had “escaped” the quality control bins. In one of the more devious schemes, a small group of employees purposely built models with erroneous details, then smuggled them out of the factory on double-decker buses. For the same reasons that coin or stamp collectors prize rare examples with forged or printed mistakes, these models were sold into the Matchbox collector market for a tidy profit.

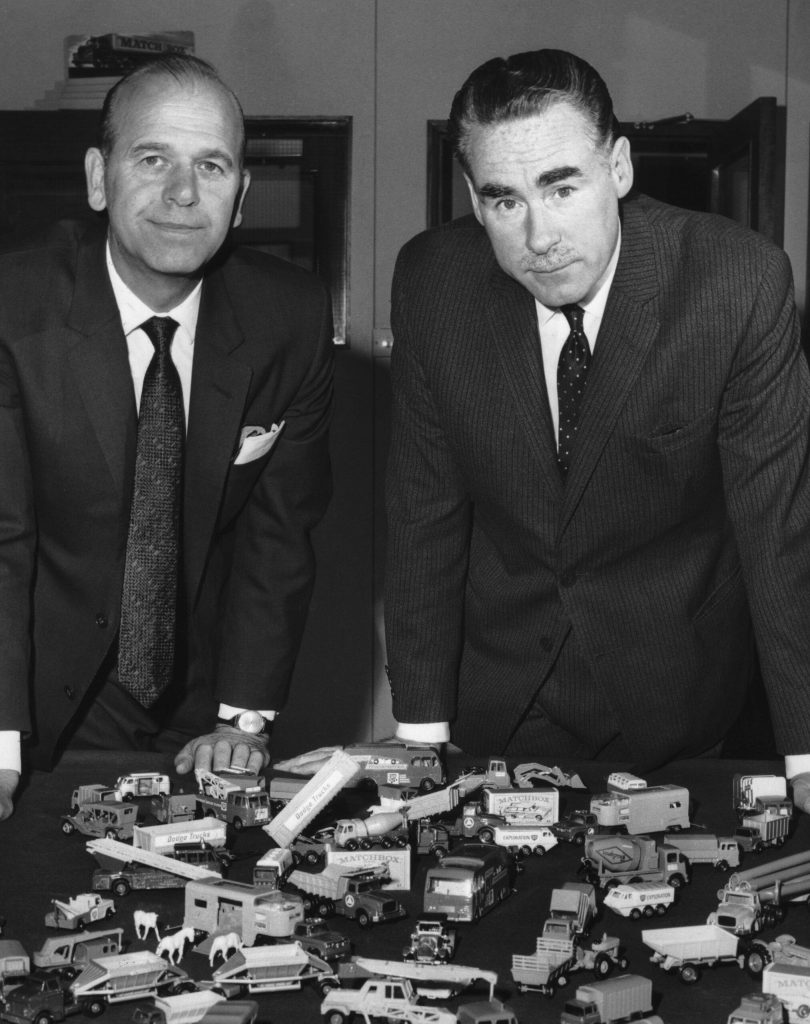

Odell was Matchbox’s mechanical genius, and a shrewd businessman in his own right, but Leslie Smith was also a big part of the company’s success. Under his direction, a large fleet of double-decker buses were purchased and repainted in yellow and blue Matchbox livery. Yes, you could buy these in 1:64 scale, but there were also full-sized Matchbox buses taking employees and their children all over town. Matchbox was possibly the only toy company in the world with its own public transit system.

Matchbox was also far and away the largest maker of toy cars on the scene, easily outperforming its former rival Dinky. By 1969, Lesney was building a thousand toy cars per minute. The models were shipped all over the world, and since the lineup included many American cars, Matchbox cars became popular across the Atlantic, too. This situation was not at all enjoyed by Elliot Handler, the co-founder of Mattel. In fact, when he saw his own grandkids playing with the UK-built toy cars, it was the match that lit his fuse.

We won’t go into a full history of Hot Wheels here, but suffice it to say Matchbox was caught flat-footed by the tiny, SoCal-infused hot rods that exploded out of the US starting in 1968. You could buy a Matchbox copy of your dad’s Austin or your mom’s Chevrolet – or you could buy a hopped-up custom Camaro with redline tires that would blow the (non-opening) doors off anything. It wasn’t a hard choice. (For further reading on the history of Matchbox cars, be sure to check out Britain’s Toy Car Wars, by Giles Chapman, and Matchbox Toys, by Nick Jones.)

Lesney pivoted quickly to a new line of cars called Superfast, but, again, hard times came along, and shares tumbled. Success returned eventually, just in time for a critical recession in the UK that would change things forever. As the 1980s dawned, the bustling industry of East End toy manufacturing came to an end. Lesney wound up its business in 1982, not out of mismanagement, but just because so many UK-based industries were dying off. The company was bought out by Universal Toys, and production moved to Macau and Hong Kong, and, later, to mainland China.

Hot Wheels and Matchbox, Unlikely Teammates at Last

After a series of business deals sold Matchbox to various owners, the brand moved under the Mattel umbrella in 1997. In those early days, there was some confusion about what to do with two similar car brands. Matchbox had sought to emulate Hot Wheels’ California car culture with its Superfast line, but the British brand and that automotive niche weren’t really a good fit. The first Matchbox was a road roller, after all, and many of the first run of models were construction vehicles. The difference between the two brands is evident even today: Whereas a Hot Wheels is designed to race down those iconic orange tracks, and often feature wild customisations or complete fantasy builds, a Matchbox is more realistic and accurate.

Matchbox vehicles are a different kind of fun than Hot Wheels. Matchbox’s lineup includes far more construction toys and trucks for kids who are into sandbox play. The 2024 lineup also has very faithful representations of cars like the Lotus Europa, first-generation Toyota MR2, and Mk 1 Golf. There’s even a Morgan Plus Four, as you’d expect from a brand with English roots. Matchbox is also setting itself apart with its Moving Parts line, which includes opening doors or engine compartments, features that used to be Matchbox hallmarks in the 1980s and 1990s. They add a layer of realism that’s a nice foil to the Hot Wheels style, which borders on the cartoonish.

Matchbox designers often work with the Hot Wheels design team, and while they are two separate divisions, there’s often a bit of back and forth. Hot Wheels is where things get more creative. If you’re designing a car for Matchbox, you’re trying to get the details right, not an easy task with such small proportions. It’s the kind of work in which Jack Odell would have taken great pride.

The end of Lesney wasn’t the end of toy making for Odell. Long ago, he’d started his own line within the company, focused on turn-of-the-century machinery – old steam-powered farm equipment and the like. After Lesney was sold off, Odell started his own company called Lledo using some of the old tooling equipment, and he worked there until 1999. He died in 2007, aged 87. His obituary in the New York Times ended as he requested: “I want it said I was a damn good engineer.”

The story of Matchbox is a great one, that of a self-made man who built a company which still brings joy to the lives of children all over the world. John Cena’s not a small guy, but he – and Mattel’s Matchbox movie – have some pretty big shoes to fill.

Very interesting read,i can still remember my 1st matchbox cars i was given as a child, 1 was a white Mercedes convertible with opening doors & red interior & the other was a light purple vintage looking car,im quite certain the vintage car was a matchbox

My Dad and his partner started Standen metal finishing that sprayed all the Matchbox toys in the Fiftys

If you’d like to explore more about the Matchbox heritage casts, the Reddit sub r/VintageMatchbox has an 800 strong group of collectors sharing interesting posts daily.

Hagery. Please don’t take this down, it’s genuinely relevant to folk that have read and enjoyed this article. (Plus, I frickin love Jasons YT content)

I am wondering how many double decker buses that were called “The Londoner” did Matchbox produce. As I am trying to find and buy them all