Angela Willis and I face each other across a thin, rickety plastic table in a Sprite 400. It’s a dull day in the New Forest, and the meagre daylight coming in through the windows is filtered through the ochres and oranges of the caravan’s thin curtains. To treat ourselves to a Nescafé on this chilly morning, we’d need to fuss around outside with a Calor cannister and a rubber tube, find some drinking water, stand over the miniature gas hob without setting fire to our scarves, and reach for the Melamine mugs… only to realise that the milk is off and an ant is burrowing into the sugar.

If this scenario reminds you vividly of a British caravan holiday circa 1971, or indeed just about any time in the 1960s and ‘70s, then we have succeeded in snagging your interest in a true classic of motoring getaways.

If we were 1970s parents then we might well have been scowling at each other, and wishing we were either back at home or else downing a final Cinzano as Mallorca came into shimmering view through the descending BAC Trident’s porthole window. For even when this Sprite was built, caravan popularity was deflating like a blow-up bed with a leaky valve, principally because of cheap package holidays where sun was guaranteed, which was more than could be said for a Caravan Club campsite near the coast. British caravans have always been more Rhyl than thrill.

However, in this case, Willis is regaling me with so much background about the Sprite that we’re both lit up like a pair of primus stoves. She is the highly knowledgeable Senior Curator of the Caravan and Motorhome Club Collection at the National Motor Museum in Beaulieu, and we are holed up in the Collection’s latest acquisition, a surprisingly desirable 1971 Sprite 400.

“It’s an incredibly significant product in the history of the caravan,” Willis explains. “It was the most successful model the company ever made, and it’s the only caravan ever to have had its own dedicated production line at the Newmarket factory because the specification was rigidly cut down to the basics, and they excelled at producing it to be as cheap as possible.”

That company was Alperson Products which, in 1963, adopted the planet-striding title of Caravans International, aka CI. Alperson’s founder Sam Alper represents the very model of a demob-entrepreneur from London’s East End. With his brother he started making caravans in 1947 from war-surplus scrap. Old barrage balloons provided roofing material and the magnesium wheels came from broken-up Spitfires.

Sam, through, was quick to up his game, and by the time he had the inspiration for the Sprite 400 his firm was one of the UK’s leading manufacturers, its revenues fuelled by rising prosperity, growing car ownership, better road links and a newfound wanderlust in British holidaymakers. Sam himself lived the dream, embarking on several epic journeys to prove his products. These included, for example, a 10,000-mile odyssey around the Mediterranean with a Sprite hitched up behind his old Jag. On another of his trips around the States, Sam became infatuated with American roadside diners, and in 1958 opened his own version back home, calling it Little Chef…

And it was his well-attuned antennae for the mass market that brought the Sprite 400 to cash-strapped families nationwide. Sam had been pondering an affordable and compact four-berther aimed at Volkswagen Beetle owners, and he pressed the button on the idea after the Mini was launched in 1959 and proved a big hit. So the small and very light Sprite was aimed specifically at owners of Alec Issigonis’s 850cc baby, and when it was launched in summer 1960 it cost £215. Willis says that equates to about £6000 today and that the Sprite was for many “the first step up from an expensive tent.”

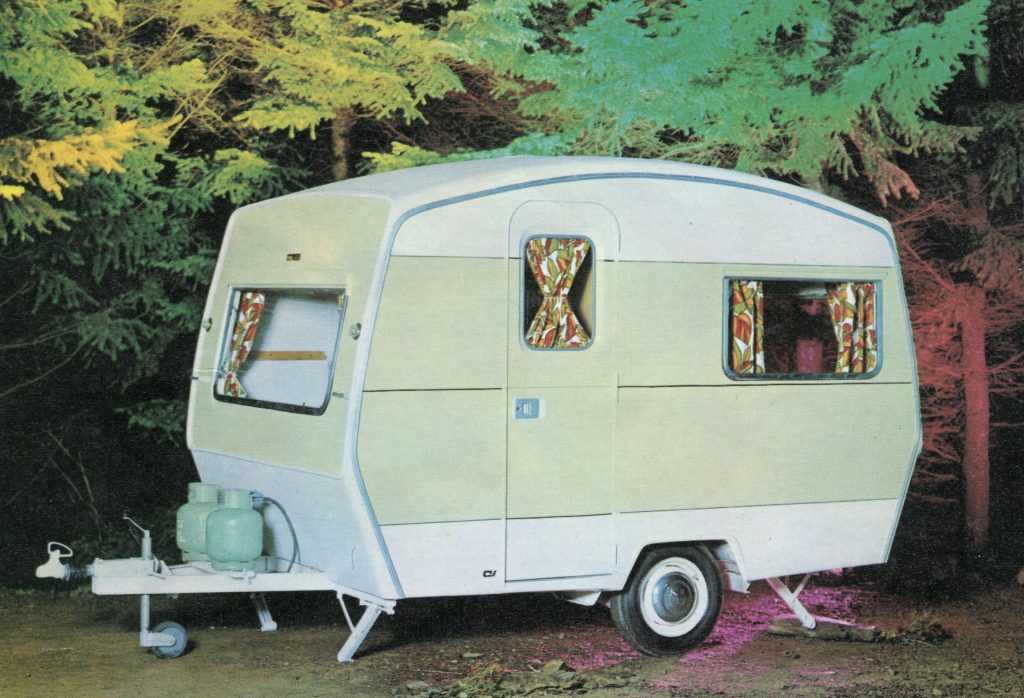

The 400 bit of the title told of the target weight of 400kg, and this was achieved through a ruthless war on heft, and materials rich in various early solvents. It all started with a new, triangulated chassis frame and leading-arm suspension on which the wood-framed, aluminium-panelled body was fitted. But it was inside where the design minimalism took over. It was a four-berth by dint of one of the two beds for children being a hammock that doubled as a seat backrest by day. The sink was made of plastic while seat bases were in hardboard instead of a timber frame with plywood facings.

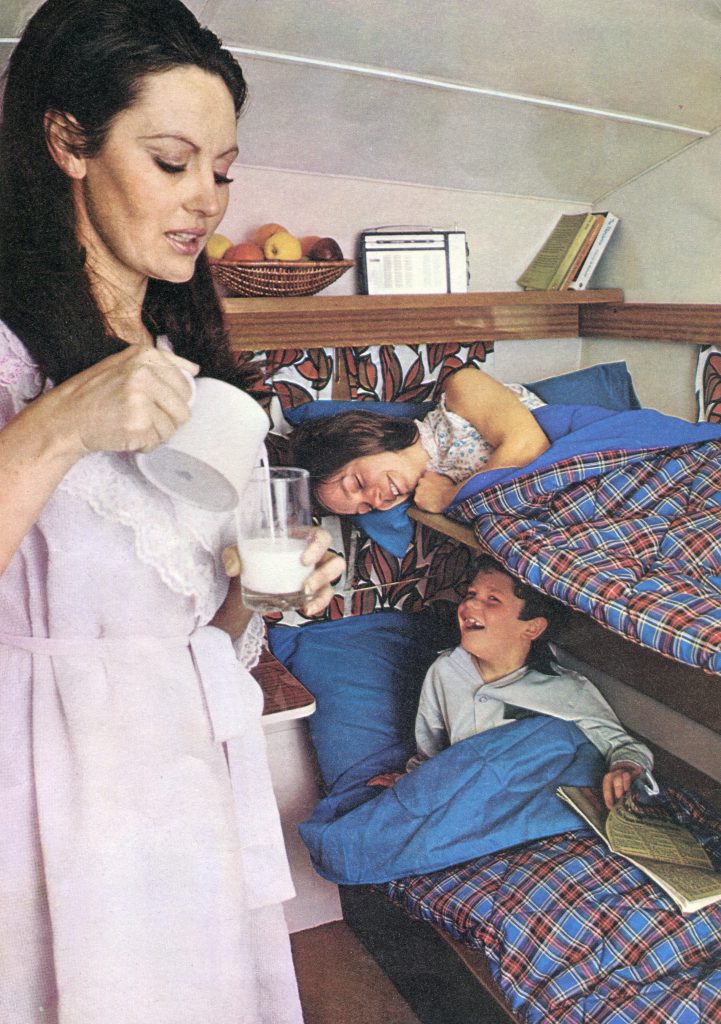

The 400 was a runaway success, although a rolling programme of design improvements (starting with glass windows to replace plastic ones) meant only the very first one actually weighed 400kg; as small family cars gained more power, so the Sprite could afford to put on a few kilos. The most significant change came in 1966 when the taller, more squared-off profile arrived that a great many of us will still recognise instantly. Then in 1970 came a hot and groovy new interior look with bright orange upholstery, a mustard-yellow linoleum floor, bold curtain material and shiny, wood-effect Formica absolutely everywhere.

This is the version we’re in at Beaulieu, and its originality is astonishing.

“For a Sprite 400, the condition is absolutely exceptional,” Willis purrs. “It’s very hard to find one now like this because so many have been lost to shabby chic and Cath Kidston makeovers. It’s completely undamaged and unmodified inside, even down to its gas-powered lighting and seat cushions that some of our junior staff have pointed out have the shape, colour and texture of large fish-fingers.”

Willis had almost abandoned hope of ever finding one in such an untouched state when, out of the blue, this example was offered as a donation by the family that had owned it from new in Marlborough, Wiltshire. The flimsy nature of the fittings and the temptation for amateur modifications usually means the interiors are wrecked. Years spent sinking into the mud and ivy of a garden, farmyard or orchard usually results in structural decay. This one, though, has somehow managed to avoid all that. Only the non-working brake needs a refurb, plus a little attention to the flaccid beading strips between the panels to stop any moisture getting in.

This is the National MOTOR Museum, though. There is no motor in a caravan, so why is it bothering at all? True, it does have a couple of caravans on display, but they’re hardly run-of-the-mill. One was a 1955 present from the Caravan Club to Prince Charles and Princess Anne, so they could experience what common people did in the summer while they were on the Royal Yacht Britannia; and another is Sam Alper’s personal Eccles caravan from the 1920s. The answer lies in ambitious plans to put the Museum on the road and take pop-up historic motoring culture to those who would never normally make the trek the Beaulieu.

“It’s going to be used to engage people with the story of motoring, doing outreach on-site at schools, libraries, care homes, all sorts of places,” says Willis. “We did the first ones in 2005-7 following the Government’s Museum for Social Change agenda, because not everyone will come to the Museum. So we’re going and seeking an audience, taking our collection out into the community. Once people have engaged, it encourages them to come and see us, and we think the Sprite is definitely a ‘living object’ that’s powerful in bringing back memories.”

That’s something Cameron Burns, founder of the website Classic Sprite Caravans (and also NotAnotherWhiteBox on Twitter), would fully agree with. “I’ve had an interest in old Sprite caravans since I was a child. My grandparents started caravanning with a 1965 Sprite 400, and when I found the original sales brochure when clearing out, I was immediately captivated by the shape and style of these iconic caravans. When I passed my driving test, I soon found myself the proud owner of a 1963 Sprite Alpine.”

Cameron now has 10 pre-1970 Sprite caravans in his collection, and his site includes a detailed history of the 400, including its many Sam Alper-generated publicity stunts, such as a 1964 attempt on the caravan towing world speed record attached to a Jensen C-V8, when it swayed and bounced its way to 101mph.

These sorts of violent, high-speed shenanigans will, of course, play no part in the future of Beaulieu’s Sprite 400. In fact, curator Willis and Head of Learning Ben Swann (who describes entering the Sprite as “giving an instant serenity”) are still working out how people can access it so its unique unspoilt condition isn’t damaged. Even I felt like asking if I should take my shoes off before stepping across the timewarp threshold into summers past…

Read more

Your Classics: The Hymermobil camper that towered over Festival of the Unexceptional

Plastic fantastic! The caravan is making a comeback and you could tow the line too

This Mini camper was a big project on a small budget

I’d take issue with caravanning being in decline by the 60s. My parents upgraded from canvas mid 70s and we spent every Easter at a packed caravan site, usually in the New Forest, then three weeks traveling through France via many a packed site to a packed to the gunnels camp site on the Costas.

Not everyone wanted a package holiday.

My mother bought a brand new Sprite 400 in 1972 for £375 and was still using it in 2012 when she was 89 towing it behind a succession of cars including an Austin A35, several Chevettes and a Citroen saxo. She often took her grandchildren off to Cornwall and Wales and it was a goldmine of happy memories.

As an impoverished parent with two small lively children I purchased a 1978 Sprite 400 from a neighbour in 1985. With the addition of an Auning it provided totally adequate family holiday accommodation for many years and is still remembered with great affection.