Emile Leray is already a seasoned automotive adventurer when he sets out from the Moroccan city of Tantan to cross the Western Sahara in his trusty Citroën 2CV. His target is Zagora, approximately 400 miles northeast across the desert.

Leray is well prepared, with ten days’ worth of supplies and a loaded toolbox. He’s travelled through Morocco many times before, but even he couldn’t possibly anticipate what he’d have to do to survive.

It’s March 1993 and the Western Sahara is a dangerous place. Not just because of the soaring daytime temperatures which plummet dramatically at night, but also due to a fragile ceasefire in the civil war between the separatist Sahrawi Polisario Front and the Moroccan government.

Military checkpoints are installed at regular intervals and it is just a few miles into his trip that Leray encounters such a roadblock. He is ordered to turn back and return to Tantan, but instead, he comes up with a plan to avoid future blockades and continue his journey by leaving the road and pointing his 2CV up a rocky track instead.

For a while it’s bumpy but steady going, the Citroën’s legendary long-travel suspension and lightweight allowing it to cope with obstacles that would strand many a modern 4×4. He starts to relax. This is going to work.

Then a momentary lapse in concentration dashes the 2CV into an unforgiving rock. A front wheel buckles under the car as the front suspension arm folds in half. It’s going no further.

The obvious move is to backtrack to the main road on foot, hope for a ride back to Tantan or even walk the whole way. Instead, Leray decides to engineer his way out of the situation.

The 2CV’s engine and transmission are still working, and he’s still got three useable wheels – but if all goes well, he’ll actually only need two of them.

During his first night under the desert sky, Leray draws up blueprints in his head. With the tools he has available, he reckons he can remove the body, wheels, suspension, and powertrain, then cut down the chassis with a hacksaw and re-install the engine and transmission with a single wheel at each end.

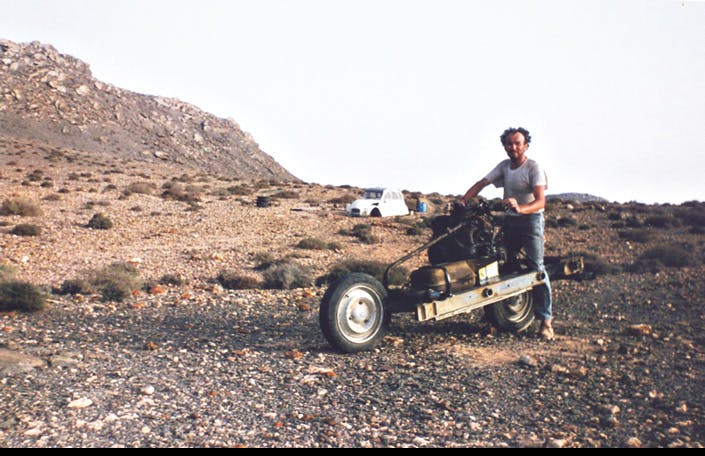

It’ll take three days, he figures, but it turns out to be an exercise that takes another 11 days to complete. Leray toils away, the searing heat testing his ingenuity, and does his best to sleep at night, the shell of the 2CV protecting him from the elements. He ekes out his rations, but even so, by the time his two-wheeled 2CV is ready for a test ride, he has precious little food and water left.

The machine is incredibly awkward to operate, has no brakes, and no exhaust system so it belches fumes in his face as he attempts to ride it for the first time. It does not go well.

The bike tumbles sideways and Leray fears he will be trapped under its 400-pound weight, yet he manages to get out from under it in the nick of time. He perseveres and slowly makes progress, reckoning he’s proficient enough to attempt a ride to safety the next day.

He clears his campsite, neatly stowing unused parts and gear in the 2CV’s shell, packs his remaining provisions and a makeshift tent, and heads off. It’s incredibly tough riding and Leray doesn’t make it very far before deciding to make camp and try again the next day.

In the night he is awakened by soldiers who have stumbled across his camp. He tries to explain his predicament, but the military men are unconvinced. Eventually, they agree to take him in their 4×4 to find the remains of the Citroën.

With his story confirmed, Leray is told to ride his contraption back to Tantan, and the soldiers follow him. It’s slow going, with rider and machine in anything but harmony and Leray repeatedly falling off. Eventually, another 4×4 is called out to haul the battered bike back into town.

He’s met not with praise for his engineering efforts and survival instinct, but with a hefty fine for driving a non-conforming vehicle.

Leray has to return to his native France without his life-saving machine, but comes back a month later to collect it – in another Deux Chevaux, of course. Since its desert adventures, the two-wheeled 2CV has been exhibited across the world, while Leray has gone on to build an amphibious Tin Snail and various other oddities.

Looking back with 30 years of hindsight, it may well have been easier for Leray just to walk to safety, but we would hardly still be talking about him if he did.

If he still had 3 usable wheels, it does rather beg the question why he didn’t just build a tricycle? Would have saved himself the issues of balancing, surely?

He broke down 20 miles from Tantan. He had enough food and water for ten days. Why not just walk back to Tantan?