Captain George Eyston already had one Land Speed Record to his name when he was preparing for the all-important return run at the Bonneville Salt Flats on 24 August 1938.

Having clocked 347.155mph through the mile on the outward run, a second record looked likely.

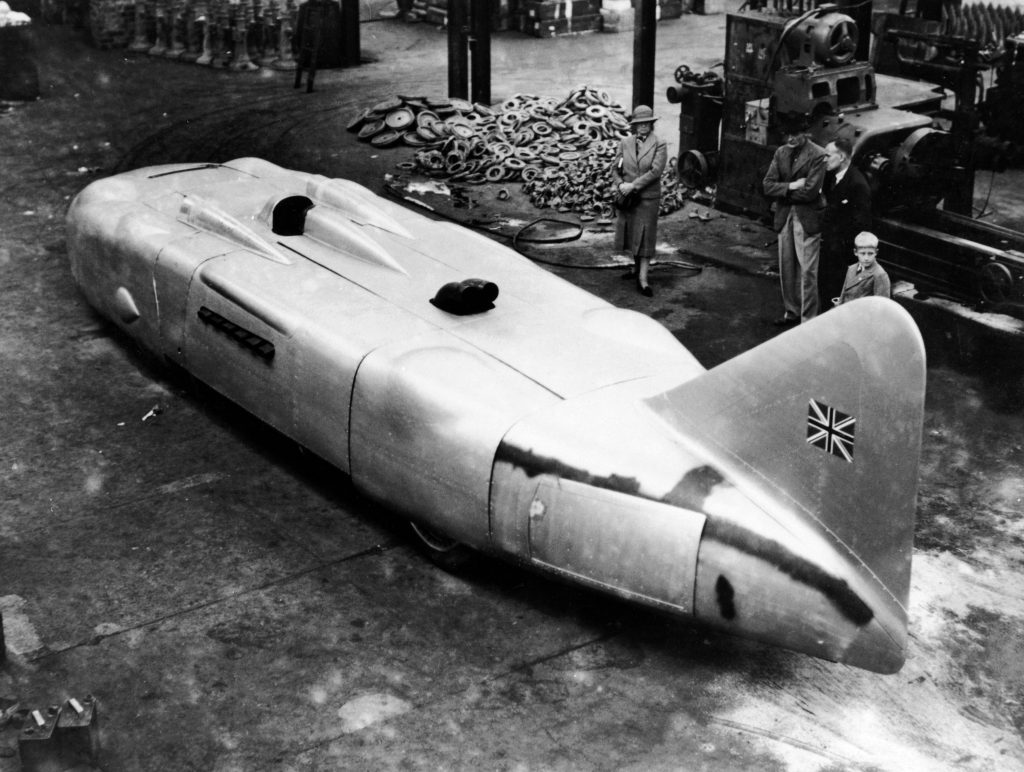

Unfortunately for Eyston, the shiny Birmabright aluminium skin of his six-ton behemoth failed to trigger the ‘magic eyes’ timing beam, leaving the time unrecorded.

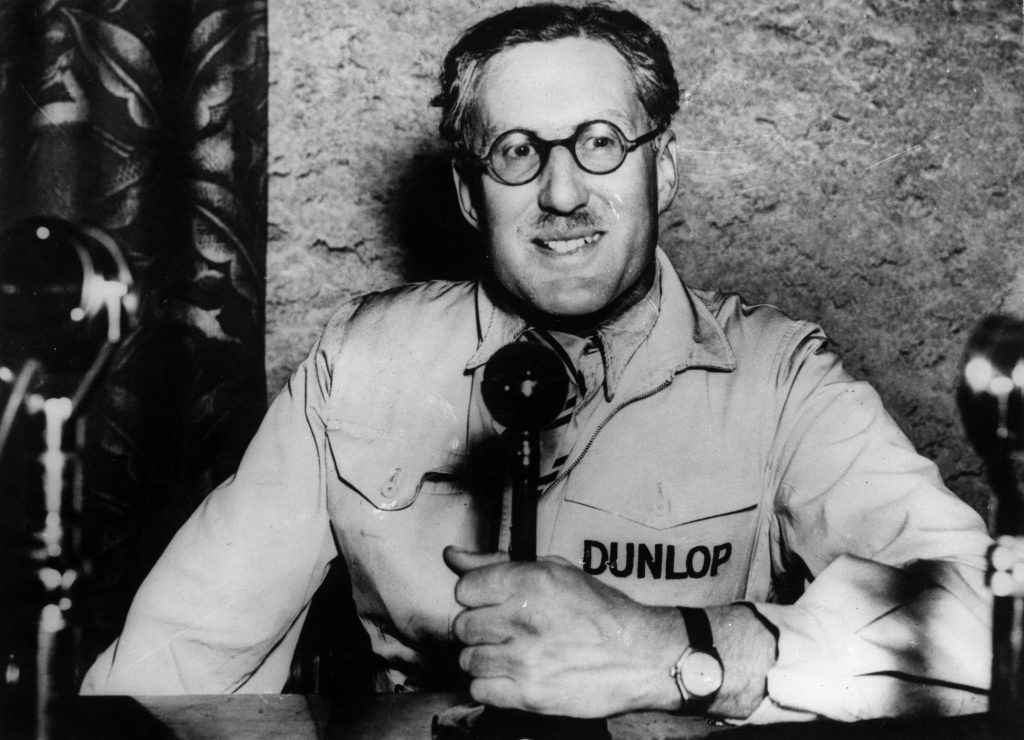

According to a 2019 Classic & Sports Car article, Eyston was philosophical, saying: “I am becoming used to the speed and don’t now have the sensation of the earth curving down in front of the car. The only way to describe how I feel is that I’m whistling through space.”

Such calmness under pressure and composure in the face of adversity is unsurprising when you consider Eyston’s back story.

‘Whistling through space’

At the age of 20, Eyston was awarded the Military Cross for ‘conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty’ during the First World. In 1938, he received France’s highest honour, the Légion d’Honneur, and although he was awarded the OBE in 1948, a knighthood escaped him.

When asked if he felt aggrieved that fellow Land Speed Record holders Sir Malcolm Campbell and Sir Henry Segrave had been so rewarded, he told Bill Boddy, ”No, I regard my Légion d’Honneur as the equal…”

Motor racing historian Doug Nye said he had never heard anyone have a bad word for him, while Phil Hill described him as “a prince amongst men”. “Eyston was essentially a gentleman,” said Boddy.

Injury ended his military career, so Eyston resumed his education at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied engineering and captained the college boat club.

While on holiday in France in 1921, Eyston stumbled across the Italian-born American racing driver Ralph DePalma practising for the French Grand Prix on the roads around Le Mans. The following year he watched streamlined Aston Martins racing at Brooklands.

These events inspired Eyston to pursue a career in motor racing and record-breaking. Along with directorial roles at many companies, including Castrol and Burmah, he broke class records for MG as both driver and team manager, and designed and patented the Powerplus supercharger.

And yet, for such an illustrious military and civilian career, Captain George Eyston is most remembered for his exploits behind the wheel of Thunderbolt.

The story of three Land Speed Records begins in 1935 at Bonneville, where Eyston set a 24-hour speed record of 140.52mph in Speed of the Wind. A year later, he set a new record of 149.096mph, before being eclipsed by John Cobb in the Mormon Meteor.

Between them, the pair were responsible for raising the Land Speed Record from 300mph to nearly 400mph in just a decade.

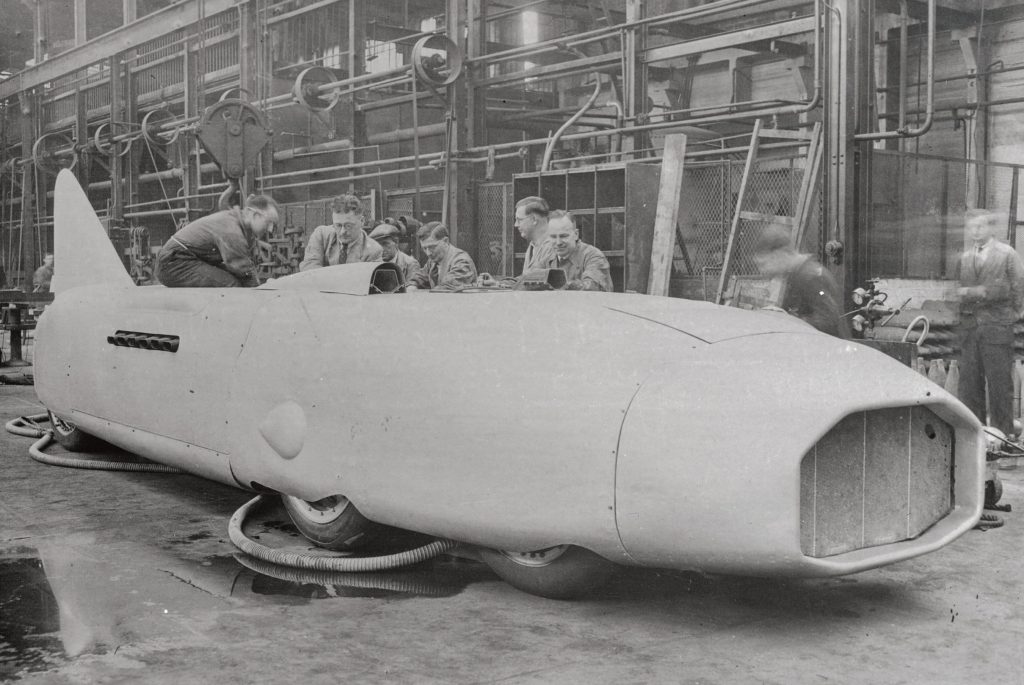

Eyston’s challenger for beating Malcolm Campbell’s 1935 record was Thunderbolt, built at the old Bean Cars works in the West Midlands. Developed over seven months with the help of his friend Ernest Eldridge, Thunderbolt was assembled in just six weeks before being shipped to the US.

One Rolls-Royce V12 engine good, two better

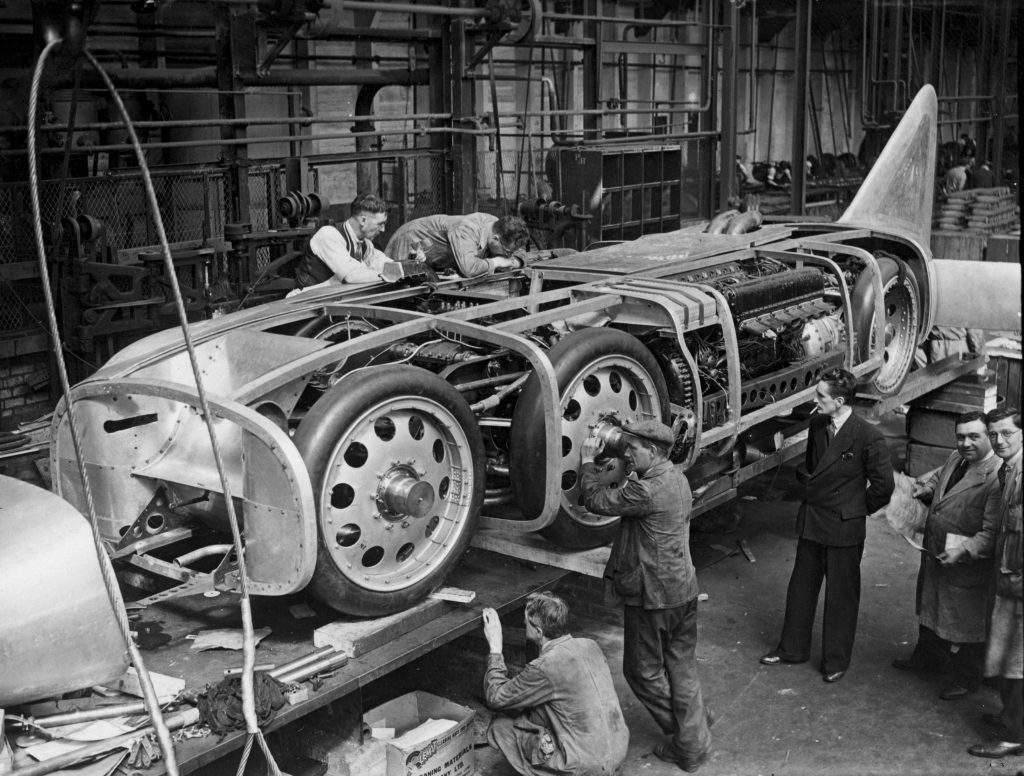

It drew its tremendous power from a pair of Rolls-Royce R V12 engines developed for the Schneider Trophy, an air race for sea planes and flying boats. Just 19 units were produced, with each engine reused several times in air, land and water racing and record attempts.

At a cost of £5800 in 1930 – the equivalent of £305,000 today – Thunderbolt’s pair came with genuine provenance. R25 was used to power the victorious Supermarine S.6B at the 1931 Schneider Trophy, while R27 was used to power the same aircraft to an air speed record of 407.5mph.

The engines were mounted side by side behind the driver, with the power – a combined 4700bhp – sent to the four rear rear wheels by a gearbox extending to 5ft 6in in length and weighing a ton. Up front, there were four more wheels on two axles, the front pair having a narrower track than the following pair. Squeezed between these, somehow, just ahead of the vast Rolls-Royce V12s, was the fearless helmsman.

In its original form, Thunderbolt weighed a not insignificant seven tons, but Eyston believed that heft was the key to success. In 1939, he recalled: ”In order to transmit a certain horsepower, there must be a certain weight pressing down upon the driving wheels to give proper adhesion.

“A car as light as those developed by the recent Grand Prix formula is admittedly a marvellous piece of engineering, but for safety at over six miles a minute, I would rather sit inside the solid bulk of Thunderbolt.”

It remained the longest and heaviest Land Speed Record car until the arrival of Thrust SSC in the 1990s.

Thunderbolt also featured inboard brakes designed and patented by Eyston, four wheels up front for steering, 7.75-inch by 44-inch Dunlop racing tyres and air brakes, which reportedly “shed the first 50mph or so”.

Problems with clutch and goggles

Eyston arrived in the US shattered after overseeing every aspect of the car’s build. Poor weather in Utah meant that he would have an agonising wait before he could get out onto the Salt Flats, but he still managed an impressive 309mph on Thunderbolt’s first outing. Clutch problems would prevent a return run, ending hopes of a new record – for now.

The persistent clutch problems led to a redesign, which was completed before winter hit Utah. On 19 November, Thunderbolt topped 305mph on the outward run, but on the return leg, a rag left in the cockpit blew past Eyston’s face, knocking his goggles.

Another account recalls how the goggles worked loose in the wind, but either way, this forced Eyston to drive one-handed, partially blinded, as he straightened his goggles, which makes the record time of 311.42mph – some 10mph quicker than Blue Bird – look all the more remarkable.

Eyston knew he could go faster, so he set about making changes ahead of another record attempt in 1938. Revisions included a switch to coil-spring suspension, reshaped nose and tail, larger supercharger inlets and a closed cockpit. Crucially, it was a ton lighter than before.

By now, Eyston was engaged in a Land Speed Record war with John Cobb, with the pair arriving in Bonneville around the same time in 1938. Eyston drew first blood, setting a fastest speed of 345.31mph on August 28, just three days after the incident with the timing gear robbed him a likely record.

Fearing retaliation from Cobb, Eyston made changes to Thunderbolt, removing the tail fin to reduce drag and switching from a radiator to a water tank to enable a more streamlined nose. He could only watch on as, on 15 September, Cobb’s Railton Special set a new record of 350.2mph.

Eyston wasn’t done, and, just 24 hours later, he set another Land Speed Record, with Thunderbolt hitting 357.497mph.

Undeterred, Cobb insisted that 370mph would be possible in 1939 and even claimed that 400mph “won’t be too difficult given the right conditions”. In 1938, Popular Science asked, “What will be the greatest speed man will ever attain on land?”, before suggesting that 750mph – faster than the speed of sound – would be possible.

Eyston, described by Doug Nye as “the warmer, more open and engaging of the pair”, was unconvinced. “After you pass 300mph, the graph of danger rises almost vertically and the graphs of car and engine performance drop rapidly,” he said. “Man won’t go much faster than 360 and live to tell about it.”

Unfortunately for Eyston, John Cobb returned to Bonneville in set a new record of 394.196mph, which he’d hold for seventeen years until Donald Campbell’s Bluebird hit 403.10mph on Lake Eyre. The Captain could take some comfort in the fact that Thunderbolt will remain in perpetuity as the fastest V12-engined car ever built.

Sixty years after Popular Science posed the question about a 750mph car, Andy Green did just that in ThrustSSC, with the help of two Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan engines.

From Salt Flats in Utah to being flattened in Wellington

After setting the Land Speed Record, Thunderbolt was displayed at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, before being shipped to Wellington, New Zealand, for the Centennial Exhibition. By then, the engines had been swapped for replicas; R25 lives at the Royal Air Force Museum London, while the R27 is on display at the Science Museum. The whereabouts of the gearbox is unknown.

After the closure of the Centennial Exhibition, the buildings were used as extra accommodation by the Air Force, then as a place to store wool. Thunderbolt was relegated to land adjacent to the buildings, where it became intombed by Wellington’s ever-growing wool stock.

In September 1946, a fire engulfed the buildings, destroying several aircraft and vehicles, including Thunderbolt. Its charred and rusting hulk remained there until the 1950s, when the land was cleared for the extension of Wellington Airport. There are rumours that its remains lie beneath the runway.

Captain George Eyston OBE died in June 1979 aged 82. His legacy lives on as the driver of the fastest V12-engined car in the world.

Both man and machine are immortalised in aspects of the new Rolls-Royce Black Badge Wraith Black Arrow – the last V12 coupé the marque will ever build ahead of its all-electric future.

Highlights include a glass-infused paint finish inspired by the crusted surface of the Bonneville Salt Flats, an illuminated Thunderbolt Speedform between the front seats, a fascia depicting the inner workings of a modern V12 engine, and a clock inscribed with ‘Bonneville’ and ‘357.497mph’.

Most amazing of all is the famous Starlight Headliner. It features 2117 fibre-optic stars, which depict the Milky Way and the constellations as they would have appeared over the Salt Flats on 16 September, 1938 – the date of Eyston’s final record.

Eighty-five years on, George Eyston’s star shines brighter than most.

Read more

The Black Arrow is a powerful parting shot for the Rolls-Royce Wraith

Obituary: Norman Dewis OBE, 1920-2019

Captain Not So Slow: James May in high-speed crash, filming The Grand Tour