The world’s longest-running motoring event, the London-to-Brighton Veteran Car Run, isn’t exactly a race or a rally, but more of a commemorative trial in the best sense of the words: Man, woman, and ancient pre-1905 machinery pitted against biblical weather, the precipitous slopes of the Sussex South Downs, and the vagaries of primitive mechanical devices and lambent electrics in a tough, 54-mile celebration of the passing of the Locomotives on Highways Act of 1896.

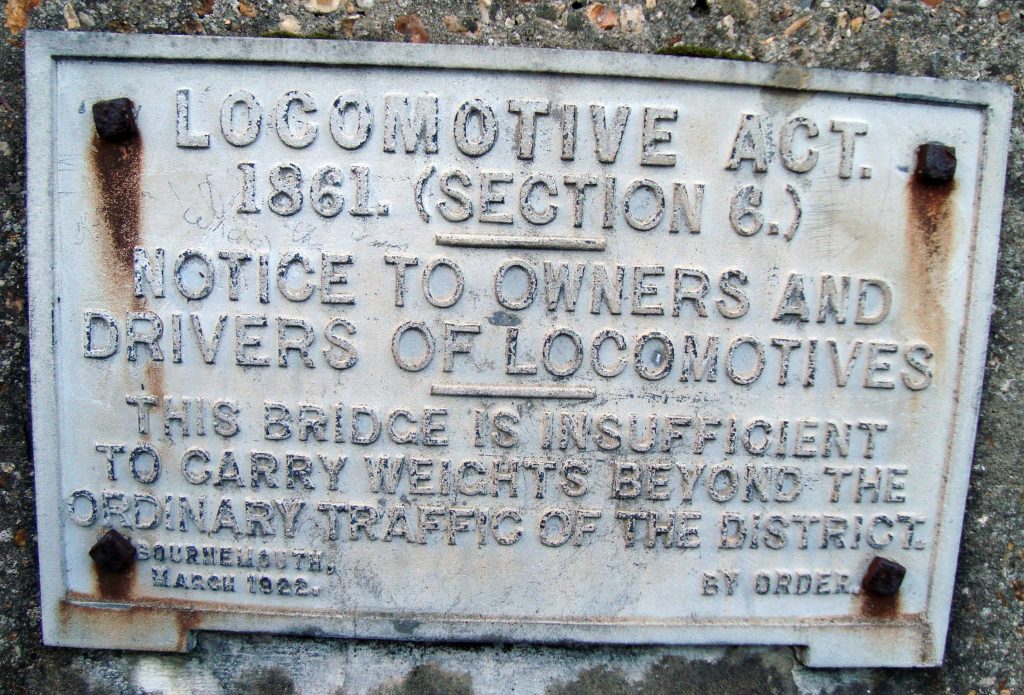

Locomotives? I hear you cry. The Locomotive Acts, whose very names denote the earliest beginnings of the motor car, were passed in the late 19th century and sought to establish a very early system of road maintenance, vehicle registration, gross weights, maximum speeds, and so on. Britain’s turnpike system of roads had faltered with the coming of the railways, and with the advent of the motor carriage, something needed to replace it. Thing is, the first Locomotive Acts were highly restrictive, mandating a top speed of just 4mph and requiring a pedestrian with a red flag to walk in front of vehicles with multiple wagons. Early motorists hated it and slightly unfairly it became known as the ‘Red Flag Act’.

The reworking of parts of the Locomotive Acts in 1896 lifted the requirement for the red flag man and raised the speed limit to a more realistic 14mph. This also had the effect of freeing up the motor industry and perhaps not surprisingly, there are accounts that leading figures within that nascent motor industry worked in the background to frame some of that liberalising legislation. Either way, the effect was to take the throttle off a burgeoning interest in private motoring. In 1904, there were just 23,000 cars on Britain’s roads, but the passing of this act spurred interest from buyers and manufacturers, and by the end of 1910, the UK’s population of cars had swollen to well over 100,000.

In its first year of 1896, the London-to-Brighton run was known as the ‘Emancipation Run’, and while it was a celebration and not a race, Léon Bollée tricycles were classified as rolling into Brighton’s Maderia Drive in first and second places, with elapsed times of three hours 44 minutes and four hours, respectively. After an initial revival in 1927, the London-to-Brighton has been run most years since and is organised by the Royal Automobile Club, which refuses to even give the final classification of finishers, preferring to merely award medals to those who have made it down to Brighton.

The next run, which starts in the early hours of Sunday, November 5, is four years short of the revival centenary, but there are plenty of other anniversaries this year, not the least of which is that of the movie Genevieve, which 70 years ago premiered at the Leicester Square cinema. Henry Cornelius’s charming comedy tells the tale of the shenanigans of Alan McKim and Ambrose Claverhouse on the 1952 London-to-Brighton veteran car run, and was a hit on both sides of the Atlantic. Starring Kenneth More, Dinah Sheridan, John Gregson, and Kay Kendall, the film also made Norman Reece’s eponymous automotive star, the most famous Darracq in the world.

It also contains one of the best drunken trumpet solos you’ll find anywhere on celluloid (acted by Kay Kendall, but actually performed by noted jazz man Kenny Baker) and a long-suffering police motorcyclist (Geoffrey Keen), who spends most of the film pursuing McKim (Gregson) and Claverhouse` (More), tersely reminding them that racing cars on the public highway is simply not allowed.

Another anniversary is that being celebrated by ‘Dreadnought’, a one-off de Dion-engined 1903 motor cycle built, trialled, and raced by Harold ‘Oily’ Karslake, chief engineer for renowned motor cycle racer and manufacturer George Brough, as well as being a resourceful motor cyclist and engineer in his own right. In the 120 years since it was built, Oily’s motor cycle has attracted many myths and legends, some of them perpetuated by Oily himself.

After he’d built it, Oily took a while to get his mostly self-built machine sorted out, and after trials he had to change the gearing to allow it to climb hills; he eventually fitted a two-speed gearbox, though that has since gone AWOL. After several touring holidays on Dreadnought, his first event was the London-to-Edinburgh in 1909, followed by the Motor Cycle Club 24 hours, over which he covered 466 miles and won a silver cup. There followed years of success in such trials-type events where Dreadnought was gradually modified and proved highly successful despite its Edwardian frame and antediluvian engine. It was still winning events in the 1940s, by then without its clutch.

In the 1950s it was donated to the Vintage Motor Cycle Club (VMCC), with the proviso that it be used. For a while now it has been an exhibit at the Brooklands Museum in Surrey where it has been fettled by a team of inventive and skilled volunteers.

Despite it being principally a run for cars and trikes, the Veteran Car Club allows a dispensation for a handful of two-wheeled motor cycles and bicycles to enter the London-to-Brighton. Dreadnought did the event last year in the hands of Mike Wild, and despite the old machine running slightly erratically in the biblical conditions, it made it to Maderia Drive.

On November 5 it will be on the start line again, with John Bottomley, 79 years old, a former director of the VMCC and an engineer volunteer at Brooklands, in the saddle. There’s a twist in this year’s run, however…

Bottomley won’t be the only member of his family entered on a two-wheeler. Phil Kirby, 52 years old, is Bottomley’s son-in-law. He’s a project manager with Network Rail and an accomplished and highly competitive cyclocross rider, and he’ll be starting the event 15 minutes before his father-in-law, at 06.45hrs.

Not racing exactly, you understand, because Kirby is on a 1901 Raleigh single-speed pedal bicycle, part of the Raleigh Collection, which also lives at Brooklands Museum. This machine, a rare and expensive item in its day, was quite advanced for the time, with a cross-over unisex frame, cable front brake, and a freewheel back brake. The drive chain is unusual, too, being a 3/16-inch pitch (unlike the more commonly used eighth-inch), which has caused some issues in fettling, finally requiring two eighth-inch rear sprockets to be precision welded together and then machined down to size, which at least goes to show the resourcefulness of the Brooklands volunteers. According to Kirby, it’s “surprisingly easy to ride, with good geometry and decent gearing.”

It isn’t often you get your hands on a rare Brighton runner, but Bottomley and I are old friends and he naturally thought a ride on Dreadnought would prove a good story. Not that I’m exactly filled with enthusiasm at the thought when I survey what looks like a butcher’s bicycle with a huge engine being started with a separate paddock starter.

Dreadnought resembles so much unfenced machinery, liable to drag you in by your boot laces, though this appears to have been pretty much what Oily wanted when he dragged the brand-new 3½hp 464cc single-cylinder de Dion engine back to Woking station as the vendor clutched his £4 10s.

Those exhaust manifolds run forward and backward from the cylinder head. Twin exhausts, because Oily thought that two would give better cylinder scavenging and so took an extra exhaust pipe from the valve pocket. It’s not the most efficacious way of improving the breathing, but it at least did no harm.

The handlebars bend backwards like those of a garden machine, and the controls are from another world. A front rod brake pulls on twin brake blocks rubbing on the inside of the rim like that of a bicycle, and a foot brake pushes a vee block into a corresponding vee-shaped channel in the rear sprocket. They’re both equally vestigial and shutting the throttle has an arguably greater effect on deceleration.

The right-hand levers control the engine’s fuelling and air supply, along with the brake. The left-hand levers control the decompressor, which makes the engine easier to spin it into life and to control the engine’s timing; retard to start and advance to run.

While there is a saddle down tube, Oily soon modified his machine so he sat on a leather saddle mounted on a leaf spring. All very comfortable as long as you don’t trap your inner thigh or certain other parts of your anatomy when mounting.

Think about it and there’s a logic to Dreadnought’s controls. You are basically controlling systems with quadrant and single-pivot levers, which on a modern machine would be handled with an electronic brain; for engine timing and fuelling think modern engine management, and the quadrant throttle and advance/retard are the equivalent of cruise control.

There are also a series of fuel taps, a tiny hidden electrical switch to send current to the trembler coil, and the engine oiling is delivered via a fearsome looking syringe. At which point Dreadnought bursts into life, flapping and shaking on its spindly rear stand as it warms. Bottomley has only just finished machining a new set of innards for the carburettor, so all eyes are drawn to the top of the engine looking for more leaks, fire, and smoke than Dreadnought customarily emits.

Dap! Dap, dappety dap, the exhaust note sets up its own staccato beat as Bottomley grapples with Oily’s coat, a singular creation made of India rubber. It was found at an auto jumble and identified by a hand-written note left in one of the pockets. It’s in amazingly good condition, but has enough hooks, buttons and flaps to bamboozle the average motor cyclist.

Bottomley gets Dreadnought running then hands it over to me. Starting on the road involves you running alongside with the decompressor pulled in, all the while gathering speed; it’s best done when travelling down hill or with a couple of burly pushers. You then simultaneously let go of the decompressor, vault over the saddle, and land hopefully with your body parts well clear of that hungry looking leaf spring. Then you juggle the throttle and advance levers and almost will that dap dap sound into existence. Easy this ain’t.

Once going, though, this is a surprisingly simple machine to ride, with lots of trail in the front suspension, which makes for a more stable machine. The throttle likes slow and tiny movements, but you can maintain speed down to walking pace, so anticipation is key and you’d need to maintain careful control of the machine’s speed on downhill slopes.

Just for academic interest, Kirby reckons the Raleigh has a ‘natural’ speed of around 15 to 18mph. He could pedal it faster, but it would be exhausting to maintain that for the whole of the run. Bottomley reckons the Dreadnought is good for around 20 to 35mph, much slower on hills, but every time it stops it needs restarting, which is also exhausting and time consuming. Nor is Dreadnought the most dependable device. The day after I conducted my test ride at Brooklands, one of the exhausts fell off, which if it occurred on November 5 would mark the end of the day.

Either way, it will be interesting to see who gets to the finish at all, let alone first, which in a way is what the London-to-Brighton is all about. And while it isn’t a race, may both of these best of men have an enjoyable and successful day in the sunshine. If you see them, give them a wave.

Having seen Dreadnought in action on the London to Brighton in years gone by, and wondered at the dexterity of its riders, this fab’ insight leaves me in even greater awe of the riders/caretakers of the VMCC. Cracking stuff, Andrew.

Thanks James, I heard from John Bottomley today. He reached Maderia Drive just a few minutes after his son in law, Phil. He blames a wrong turning which saw the Dreadnought at the bottom of a steep slope off the Sussex Alps, which the poor old machine struggled to ascend. I think many congrats to them both.

All best, Andrew