The transition from 2023 to 2024 seems a fine time to celebrate 30 years of the Aston Martin DB7, which made its public debut at the 1993 Geneva motor show and then went on sale in the autumn of 1994. Here Giles Chapman recalls his sit-down interview with the late Walter Hayes and the genesis of the car that would save Aston Martin. – ED

Nothing fazes you when you’re young. But I must confess I felt more than a little apprehensive when I approached my meeting with Walter Hayes, one spring evening in 1993. The streets of Mayfair were dark, rain-streaked and deserted, and my audience with this Pope of the high-performance church had been corralled into an after-hours 7pm slot, with 45 minutes allocated to ask my questions about the Aston Martin DB7. I imagine I was swiftly dealt with before Walter went to the opera to relax, after his last duty on one of his always-busy days.

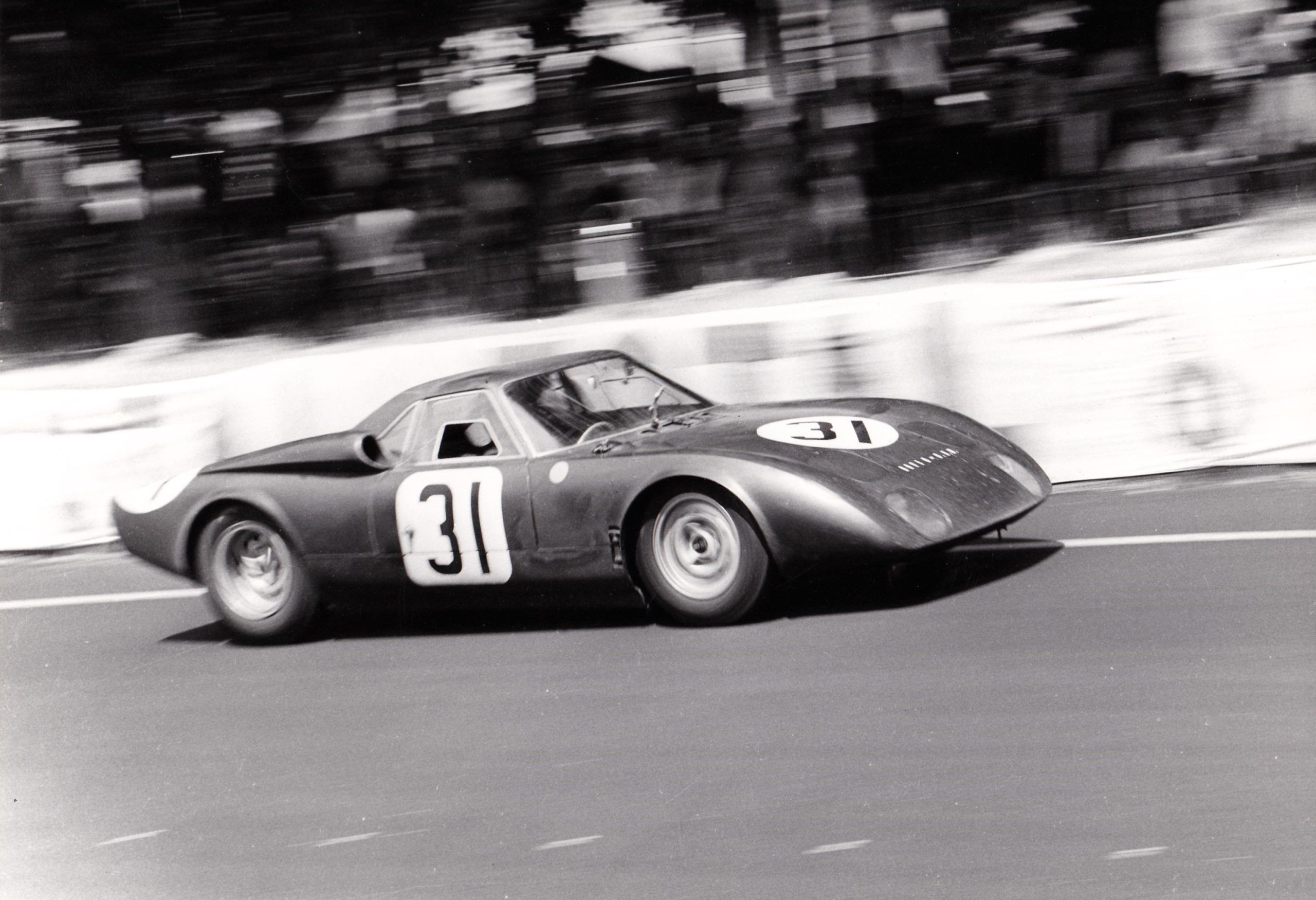

Anyone then with more than a glancing interest in cars and motor racing would have been aware of Hayes’ roster of achievements. I certainly was. He joined Ford as head of public affairs in 1962 with a mandate to help sell everyday cars through the image-enhancing medium of motorsport; subsequently he brought Colin Chapman on board to co-create the Lotus Cortina; he was instrumental in making the GT40 a four-times Le Mans winner; he linked up Ford with Cosworth to make the DFV engine that powered 154 Formula 1 victories; and he booted the Ford Escort to the top of rallying world.

But I can’t have been the only scribbler-down of Hayes’ pithy comments who found his earlier status unnerving. At the helm of the Sunday Dispatch until it merged with the Sunday Express in late 1961, Hayes had been the second youngest editor on Fleet Street, used to stepping over the threshold of No. 10 Downing Street and commissioning stories from W. Somerset Maugham. I mean, what could possibly go wrong for me, except that I’d get twisted up in my words, or ask a stupid question, or my tape recorder would malfunction? At any rate, looking like an arse of a junior writer as I sought his views for my DB7 piece in Autocar had to be inevitable.

It didn’t help that the slightly sinister building was empty, and when I stepped out of the lift on the top floor it was just me and Walt. He was a compact and dapper fellow, and my memory is still one of being intimidated by his steady, unblinking gaze, plus of course in his role of strategist and advisor he knew everyone from Henry Ford II to Jackie Stewart very slightly better than they knew themselves. His latest challenge was a mission not just to save Aston Martin but also to orchestrate its first totally new car in aeons. The latest tricky car cove he had to handle was Tom Walkinshaw, whose TWR was crucial to engineering and manufacturing the so-called Project XX (later called Project NPX), and this needed the sort of kid gloves Walter had donned numerous times in his behind-the-scenes roles at Ford.

“There was a huge aversion to Tom Walkinshaw at Ford and Jaguar,” says Walter’s son Richard, who’d worked for Walkinshaw himself and refers to TWR’s various chequered joint-ventures such as the Jaguar XJ220. “But for all his strange personal characteristics, he was very creative. Father’s view was that if you just kept him on a short leash it would work out well. Because at the end of the day, if you didn’t have the Walkinshaws of this world you couldn’t get the thing started.”

This thing, indeed, had all begun in 1987, at the elegant home of the Italian Contessa Maggi during the revival of the Mille Miglia. Walter Hayes and Aston Martin chairman Victor Gauntlett were fellow houseguests at the dinner table. Gauntlett was desperate for investment to fund his dreams of an all-new car, and the conversation gave Walter an idea.

“Henry Ford II was a big Anglophile,” Richard says. “He was really into tweeds and shooting and he supported all sorts of British things. In fact, he got an honorary knighthood later. He had a fantastic house called Turville Grange near Henley-on-Thames, and my father lived at Shepperton not far away, so they used to have dinner often, and father said ‘Look, you’ve tried Ferrari and didn’t get it, why not Aston Martin?’ Henry trusted him completely. Father even used to chair family meetings in Dearborn where Henry Ford would address them all.”

Despite Ford’s recent doomed purchase of AC Cars, the deal was swiftly done for 75 percent of Aston Martin in 1987, for an undisclosed sum that cannot have been enormous, and it was almost the last thing Walter did before he reached official retirement age at 65, overseeing the transaction in just two months.

“He had no thoughts about being involved,” says Richard Hayes. “My mother was thrilled that father was finally going to be at home and they were going to have their retirements. In 1989, though, things weren’t going very well at Aston Martin, it was going in the wrong direction. So my father was made a director, put on the board, and he told my mother it would only be a few hours a week in Newport Pagnell. He thought he’d just be giving a bit of sage advice now and again.

“But when people looked under the hood, they saw there was a bigger mess than they realised. Ford offered all sorts of benefits of engineering input and economy of scale, but I remember him telling me he was nervous Ford would come in and smother Aston Martin – to apply that budget for building everything on the same platform, and sort of crush the Aston Martin out of Aston Martin. So he kept them at bay for a year or so, and then when Victor Gauntlett resigned in 1991 father became chairman.”

A sketchy file already existed within Ford on how the new car, often also known as DP1999, could be conceived, but as almost nothing had yet been done about it, it now hinged on Walter’s ability to drive it forward, weld partnerships, and network the heck out of his contacts. Looking back at my report published in March 1993, I see he was remarkably frank about explaining it to me.

“The acquisition by Ford of Aston Martin and Jaguar has enabled it to use the resources of these specialist companies,” Walter said at the time. “I know exactly where to go in Ford for anything we might want; if you have the opportunity to use these facilities you’d be damn silly not to.

“It’s difficult to cost-control a £75,000 car even if it doesn’t sound it, but we had to set precise volumes, objectives, and price. We couldn’t have an engine that cost £21,500 and 56 hours to hand-build, and Newport Pagnell is too restricted to make a volume car – there is no room there. So we had a manufacturing challenge rather than a design one; I didn’t start where the mechanicals were concerned.”

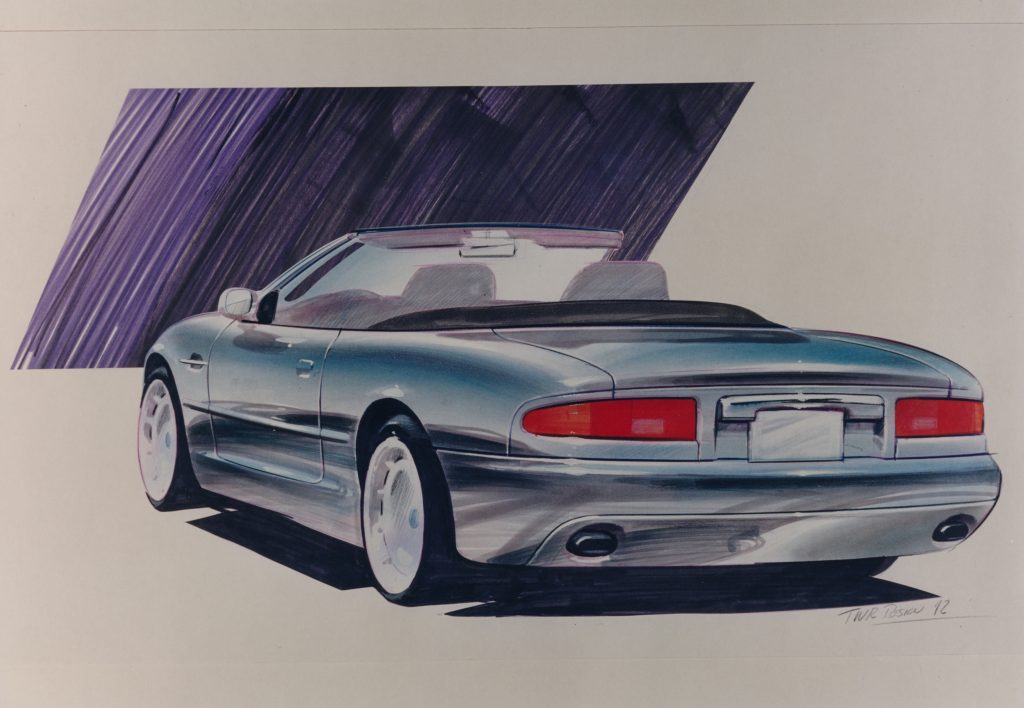

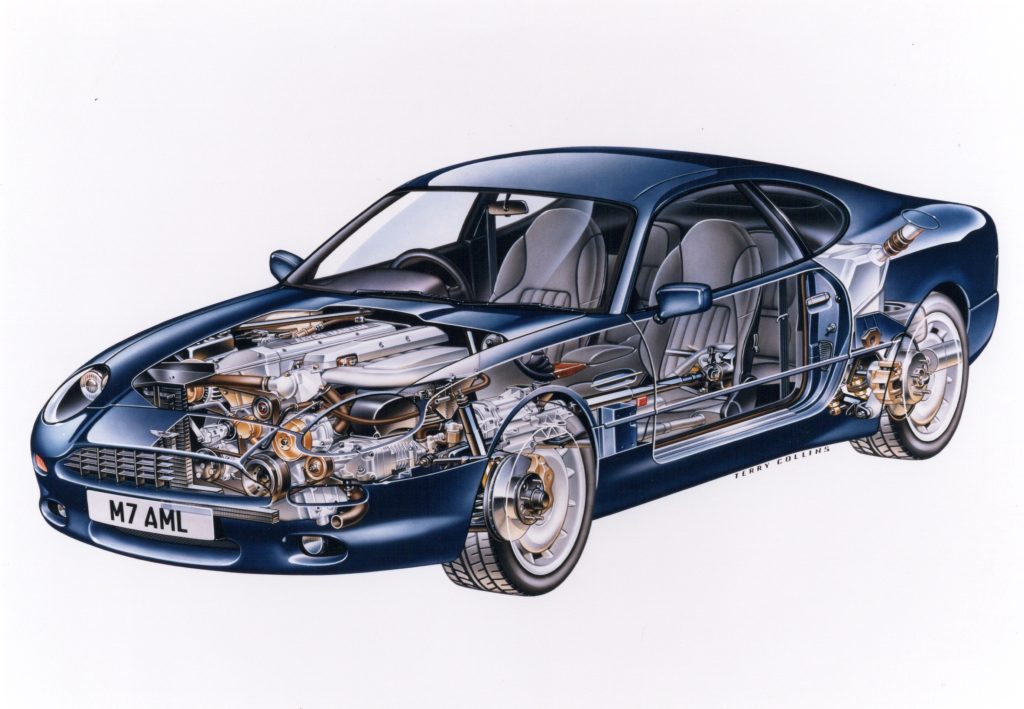

Capricious to some, maybe, but Walter Hayes was able to bring the best out of Walkinshaw. For the new small Aston, a shelved Walkinshaw concept for a super-lux Jag GT was dusted off. It rested on lots of unseen floorplan hardware from the Jaguar XJS and a supercharged version of what was, at heart, a Jaguar AJ6 straight-six engine. The ninja-engineering of the car was deftly handled by TWR/Jaguarsport, with a timeless design by Ian Callum, in a timescale that would shame car industry big-hitters, and it was much helped by full access to Ford’s extensive UK development facilities.

As Walter relayed to me in that shadowy penthouse of Ford’s London office, he rated Ian as “one of the brightest young designers I’ve come across.” The glorious work has more than stood the test of time, and some regard the DB7 as among the most beautiful British cars ever. Then again, it must have been a dream-like brief for the 38-year old Scot. Hayes in 1993 again: “We photographed the most beautiful DB4s and DB6s we could find, stuck the pictures up in the studio and said: ‘Like that’.”

Richard Hayes recalls the drive that his father poured into Aston Martin. This included not just the car itself but also, for example, motivating the dealer network and building up a new company mantra of ‘A Car For Life’ that got sales moving of that sleepy dinosaur, the Virage, for which another 50 grand was asked over the projected price for NPX. A Car For Life even got the support of Motown supremo Bill Ford, who in 1992 wrote to Walter with this endorsement: “It is a brilliant strategy, which turns Aston Martin’s low volume “weakness” into an overwhelming strength.”

Richard Hayes: “He took it pretty much through to the final delivery, using mainly his powers of persuasion and persistence and knowing what to say to who. He wasn’t an engineer or designer but was very happy to consult people and give them credit and use their opinions if he felt they were worthwhile. He liked to reverse-engineer situations to get where he wanted to end up. I remember he had to fly out to Detroit to see [new Ford boss] Alex Trotman to get him on side, and said: ‘You don’t want to be the British chairman [of Ford] who then killed Aston Martin, do you?’”

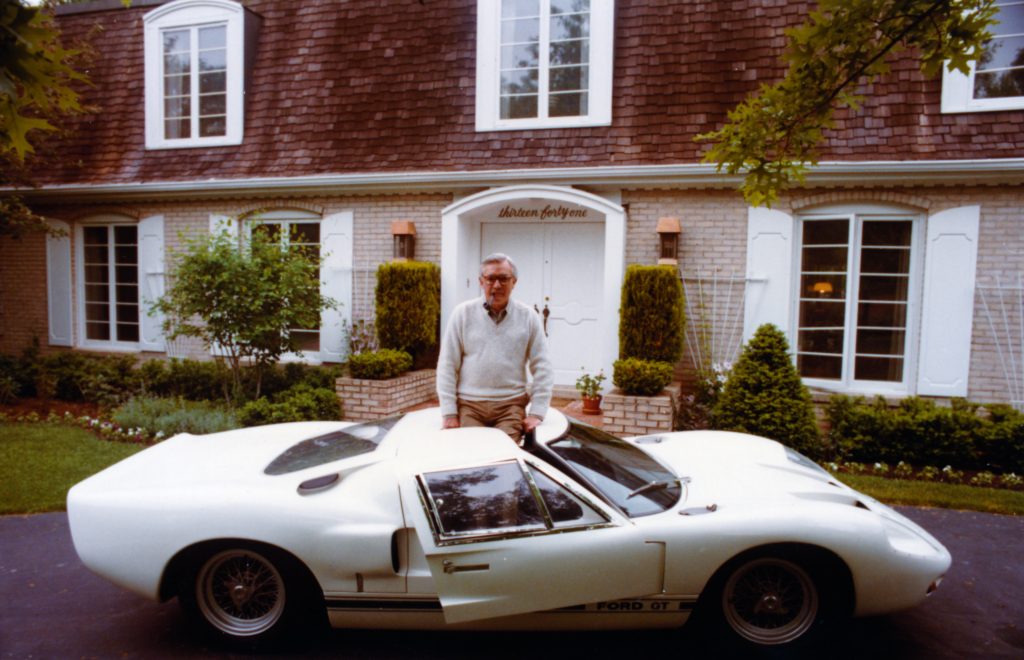

A final stroke of Walter’s velvety, diplomatic genius was in persuading Sir David Brown to give his blessing to the car, which allowed it to become the DB7 and gave the venerable former company owner from 1947 to 1972 the title of life president. There was then over a year between the DB7’s debut at Geneva and the first one rolling off the production line in June 1994 at the Bloxham factory in Kidlington, Oxfordshire (where Jaguar components were re-engineered by TWR and fitted into steel bodies – Aston’s first ever – made in Coventry by Motor Panels). A proud Walter should have been behind the wheel, his trademark subtle smile clear to see. But delays of six weeks pushed the momentous day beyond his 70th birthday and Ford’s you-have-to-really-stop-now pensioning-off deadline. His parting gift was to be made the next life president, as Sir David Brown had recently passed away. When the Aston Martin Owners Club created the Aston Martin Heritage Trust in 1998, Walter was elected its first chairman, a position he held until his death at age 76 in December 2000. During his time there, he established the annual Aston Journal and edited the first two editions, in 1999 and 2000.

The effect of the DB7 on Aston Martin was seismic. From selling 209 bespoke cars in 1990, the company delivered over 600 production-line DB7s in the first year alone, going on to build more than 7000 examples altogether, including the Volante convertible and the V12 Vantage.

“My father didn’t really blow his own horn,” says Richard. “He liked to move on to the next thing without making a fuss, but even five years after he retired it was still very important to him.

“His advice was always on-the-one-hand and then on-the-other. He’d never just tell me what to do. I used to call him saying what do you think, and when I got home there’d be a two- or three-page fax hanging out the machine. I read them and then threw them away, which I now regret!”

Walter Hayes was an influencer before we even used the word. He turned out to be a great interviewee to this writer, and although he might be bashful at the description, he was Aston Martin’s most visionary saviour of all.

With thanks to Richard Hayes and the Aston Martin Heritage Trust. Learn more about the remarkable career of Walter Hayes at www.walterhayes.co.uk.