At 94 years old, Carrozzeria Pininfarina has designed the dream cars of more than a few generations. It doesn’t matter if you love the Ferrari 250 GTO of the 1960s, the Ferrari F40 of the 1980s, or the Ferrari Enzo of just 20 years ago – each is the work of the Turinese firm founded by Giovanni Battista Farina. Tenth of eleven children, he was called “Pinin” by his family, and the nickname stuck. His company created many unattainable beauties, but also some special cars that almost anyone can afford.

Those machines are special for what they are and how they drive, but also for where they come from. In the 1920s and 1930s, if you were an Italian coachbuilder, Turin was where you wanted to be. Farina’s brother, Giovanni Carlo, set up his design business there in 1906. He would come to employ more than a few influential stylists. Felice Mario Boano, who drew the VW Karmann Ghia and the Lancia Aurelia, worked for him until 1930. Alfredo Vignale, later of the eponymous coachworks, started under Giovanni as well, as did Giovanni Michelotti, the man behind too many Ferraris, Triumphs, Lancias, and Maseratis to name.

Still, Pinin would take the surname the furthest. The young Farina set out on his own, building bodies for Hispano-Suiza, Fiat, Rolls-Royce, and others. A partnership with Lancia helped his company become one of the first coachbuilders to master unibody construction. When World War II destroyed Pinin’s factory, he started over with a will. He rebuilt his facilities from scratch and set about growing into Turin’s premier coachbuilder.

The Early Days, or How to Get into MoMA

The little Cisitalia 202 coupe is probably the single most important design in Pininfarina history. Its smooth and elegant lines evoke the 1950s, but the shape was born at the end of 1945. The 202 was the firm’s most famous work but hardly a commercial success – Cisitalia would go bankrupt less than 20 years later – but its design and quality workmanship established Pininfarina’s bona fides. To this day, a 1946 Cisitalia 202 GT lives in the permanent collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Even more of an upset was the 1946 Alfa Romeo 6C 2500 roadster that Farina drove to the Paris motor show that year. Built on one of just six prewar Alfa Romeo chassis to survive the bombing of the Turin factory, the car’s streamlined body was stunningly avant garde. What Farina did with it upset the French greatly.

Italian automakers were banned from the Paris show, but Farina turned up anyway. He parked the Alfa directly across from the show’s front doors, complete with a little Italian flag on the hood. Show organisers went nuts, but their fury was mere encouragement: The next day, Farina parked the car in front of the doors again. French newspapers and magazines ran angry comment, but the emotion just seemed to spur him on.

The Ferrari Years: A Delicate Balance

In 1961, Pinin and his brother, Sergio, legally changed their surnames to Pininfarina. The move was telling; in a few short years, their company had become near shorthand for the best in Italian styling. Much of this was due to the Farina family relationship with Ferrari, which meant, of course, a relationship with Enzo Ferrari, the carmaker’s legendary founder.

As Sergio told it, the dance between Battista and Enzo was delicate. Here were two great men, but also two great egos. Would Mr. Farina come to Modena? He would not. Would Mr. Ferrari deign to visit Turin? Forget about it. The two men had first met at the 1950 Turin auto show, where they basically just stared at each other over lunch. There was a mutual respect, but neither wanted to be the first to reach out.

Sergio laboured to solve this. In concert with a veteran Maserati racing driver working on behalf of Ferrari, he arranged a meeting. Farina and Ferrari came together at neutral ground, at a restaurant equidistant from the headquarters of each. An agreement was made. On the drive back to the office, Battista put Sergio in charge of the new partnership.

The first Pininfarina Ferrari was the elegant little 212, unveiled in 1951. The relationship that created it would continue through six decades and dozens of new Pininfarina-styled Ferraris, ending only in 2012. In that time, there were Pininfarina Ferraris of both heart-stopping elegance and forgettable shape, but every one of those machines carried a bit of Battista’s magic.

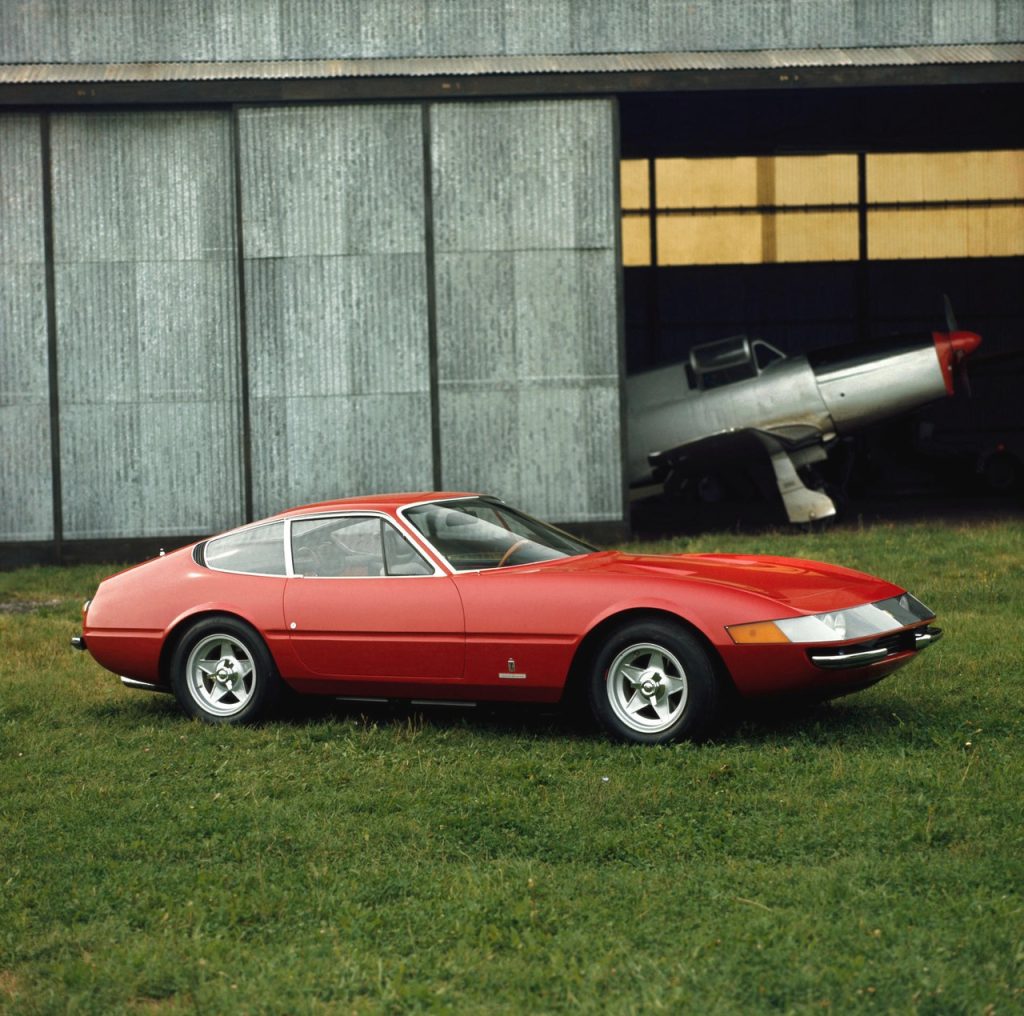

The standouts became watermarks, cultural touchpoints whose elegance and influence are still discussed today. In the 1960s, it was the 250 GT Lusso. Into the 1970s, there was the 365 GTB/4 Daytona. In the 1980s and 1990s, Pininfarina gave us the Testarossa and the F40.

But again, that age came to an end. The last Pininfarina-influenced Ferrari was the F12berlinetta, produced from 2012 to 2017. Behind the wheel, Ferraris are still as vicious as ever. But they are arguably no longer as pretty.

The Italian-American Highlight Reel

Let’s rewind a little. In the years immediately following World War II, many partnerships were formed between American carmakers and Italian coachbuilders. Ghia would come to have huge influence at Chrysler, for example. But America came knocking at Pininfarina’s door as well, and she did so more than once.

The first collaboration was with the oft-overlooked Nash-Kelvinator. In the mid-1950s, that company – the result of a merger between automotive firm Nash and appliance maker Kelvinator – would absorb the American carmaker Hudson to become the conglomerate known as American Motors Corporation, or AMC. Before that, however, it was simply a small and slightly wacky corporate tie-up whose product line included a car called the Rambler and a refrigerator dubbed Foodarama.

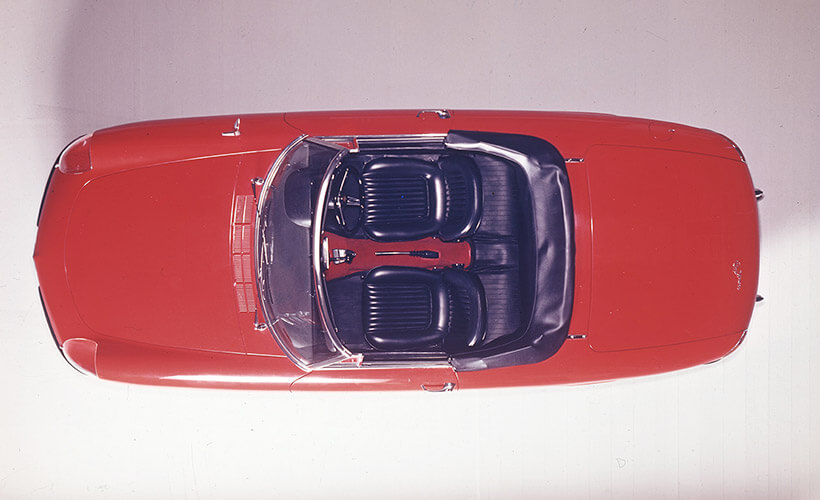

Pininfarina helped with a number of Nash designs, most notably the small and elegant Nash-Healey Roadster. Built from 1951 to 1954, these open-topped sporting machines beat the Corvette to market by a couple of years and are generally seen as the first postwar American sports car. Nash-Healeys were never built in America – assembly took place in either England or Italy, depending on model year – but they were a valiant effort in the field, competing at both Le Mans and the Mille Miglia.

Speaking of Corvettes, General Motors did commission from Pininfarina a one-off example of the model, built in 1963. The Chevrolet Corvette Rondine concept is the work of American-born Tom Tjaarda, who worked for Pininfarina during the first half of the 1960s. (Among other Tjaarda efforts: the DeTomaso Pantera and the Ferrari 365 California.)

General Motors would again turn to Pininfarina for the two-seat 1987–93 Cadillac Allanté convertible, one of the most accessible Pininfarina works. During production, those cars were famously flown between Turin and Detroit at ruinous expense. Like so many things Italian, that arrangement was a debacle at the time but later made a fantastic story.

Affordable Pininfarina Classics

It might seem odd, to go from groundbreaking four-wheeled museum piece to million-dollar Ferraris to a 1990s Cadillac coupe. But that is the great thing about Pininfarina: A piece of the house is within reach of almost any enthusiast.

Take the MGB GT – the two-door, fixed-roof sports car made from 1965 to 1980. Like the MGB roadster it was based upon, the GT was affordable when new and remains so today, but the coupe is weathertight and more elegant. You need to know your way around a wrench to keep any MGB on the road, but the GT’s classic looks are right up there with any expensive coupe of the 1960s. Solid driver examples can still be had for four figures.

For smaller pistons but just as much fun, try importing (or purchasing from an importer) a Honda Beat. This Japanese-market “kei” machine, built from 1991 to 1996, is a mid-engined, folding-roof sports and city car of just 656cc. It offers a hummingbird’s thirst for fuel and was one of Pininfarina’s first properly mass-produced designs. Like any small Japanese car, a Beat is proof that engine size and entertainment don’t always go hand in hand. Solid examples already in America are priced about like a good used Honda Civic.

Want an Italian car from Italy’s best-known coachbuilder? You have a host of options. The 1966 Alfa Romeo Duetto Spider was Battista Farina’s last design work before changing his last name. The car was unveiled only a month before the great man’s death, but the Spider remained in production into the 1990s. Late examples are more comfortable and practical than early ones (the tradeoff is a bit more kerb weight), and good runners can still be found for not much money.

Last but not least, even more accessible fare came from Pininfarina’s partnership with Fiat. A 1969–77 Fiat 130 coupe is not an easy car to track down, but it’s a visual sibling to the 1980s Ferrari 400. The 1966–85 Fiat 124 Sport Spider offers true coachbuilt flair for the masses. Also interesting is the Fiat Coupé of 1993 to 2000; the visuals of that revolutionary front-drive wedge are an acquired taste, but the car is an excellent example of 1990s Italian futurism.

That, then, is the magic of Pininfarina – the firm’s stylists put just as much thought and heart into a Fiat coupe as they did a Ferrari Lusso. The exotics are beautiful, of course, and we love to see them on posters or at shows. But as the saying goes, great design is egalitarian. The dream of art, available for all.