The 1980s – plus a few years either end – was a Golden Age of touring car racing. Elevated from European to World Championship status in 1987, its surging popularity proved to be its undoing: those ruthless bosses of Formula 1 did not look kindly upon this uppity rival.

Competing using cars emerging from their factories was a powerful publicity hook for manufacturers and generated tribal support among customers, as acknowledged sporting makes BMW and Jaguar battled to sustain legacies by fending off parvenus Rover and Volvo. The latter pair quite fancied a piece of the action and the sales’ pie chart, thank you, and no quarter was given, neither on the track nor in the courtroom.

A showroom showdown, the rivalry between the Brits and the Continentals was obvious – but there were murkier (un)civil wars, too.

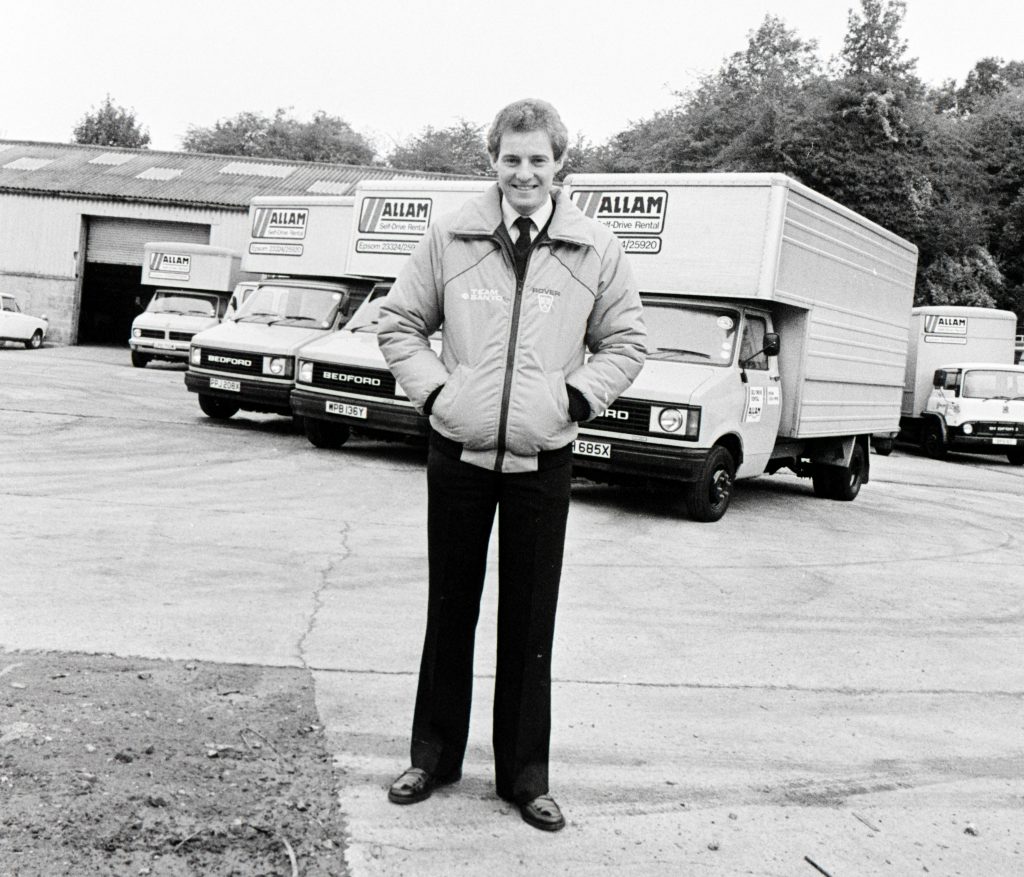

In the midst of this shooting/shouting/barging match, keeping head and foot down, was Surrey’s Jeff Allam. His racing CV is rare in that it includes a quartet of tip-top British tin-tops: 3-litre Capri, Rover SD1, Jaguar XJ-S and Ford Sierra Cosworth RS500. In other words, for the race fans who remember the heady days of touring cars at its very best and want to know what it was like to drive the star cars, Allam is the driver to ask.

In them he shared victory in this country’s oldest race with an ex-F1 world champion, finished runner-up on racing’s holy Mountain Down Under, and had a happy knack of winning in front of packed British Grand Prix crowds. Along the way, he matured from young hotshoe to wiser old(er) hand, and from elbows-out sprinter to neck-in marathon man.

“I always wanted a tin roof over my head,” he says. “I never wanted to drive a single-seater.” For the purposes of this article we can draw a veil over his 1980 one-off in an F3 March.

“Dad had nothing to do with racing throughout his business career, but there were a couple of staff at his garage [Allam Motor Services of Epsom] who were keen spectators, and they dragged me to Brands Hatch and Silverstone. That’s how I caught the bug.”

A Vauxhall Viva GT built, prepped and tweaked by a former Cooper and McLaren F1 mechanic sent a 19-year-old Allam on his way in 1973. Four years of club racing later he impressed in Class B of the British Saloon Car Championship in a 2.3-litre Vauxhall Firenza Magnum.

“We were just a bunch of amateurs, a family team, learning as we went – but we wanted to move up to the top class. So we bought a second-hand Capri MkII – an early one with square headlights – and converted it.

“Then one day, unannounced, a brand new Capri MkIII in virginal white arrived at the garage on a trailer, and with a letter from the sponsor: ‘This is for you.’ I talked to the donor on the phone and put his firm’s name down the side – only for him to tell me to take it off: ‘My Dad doesn’t know I’ve taken money out of the company!’

“My Dad’s secretary kept a tally: we spent £25,000 on a year’s racing: tyres, fuel, the lot. We stayed in caravans rather than hotels.”

Thus armed with a car built by renowned CC Racing of Dave Cook and Peter Clark – “the bees’ knees” – that was a match for of any Capri on the grid, Allam’s results improved immediately and markedly in 1978.

His promise was confirmed when Gerry Marshall – the larger-than-life ‘King of Saloons’ of the 1970s and almost as well known as James Hunt – agreed to co-drive with him in the Spa 24 Hours.

“Gerry really taught me how to drive a racing car,” says Allam. “He never gave me any lessons but gave me lots of advice. I learned what it was all about by following him on the track.”

Those myriad Capris were almost unbeatable – but the British championship then was decided on a class basis dictated by engine capacity: Allam’s finishing second in the fiercely competitive Class A of 1979 was only good enough for eighth overall in the final standings. (The champion that year drove a Mini Clubman). But it was good enough to land him his first paid works drive.

Rover’s SD1 – ‘the poor man’s Ferrari Daytona’ – had the advantage of a lightweight 3.5-litre V8, but the iron-blocked V6 Capri still held sway. Allam won just once in 1980 – repeating his 1978 victory in the British GP support race: “I won because it wore Dunlop stickers but Michelin tyres.”

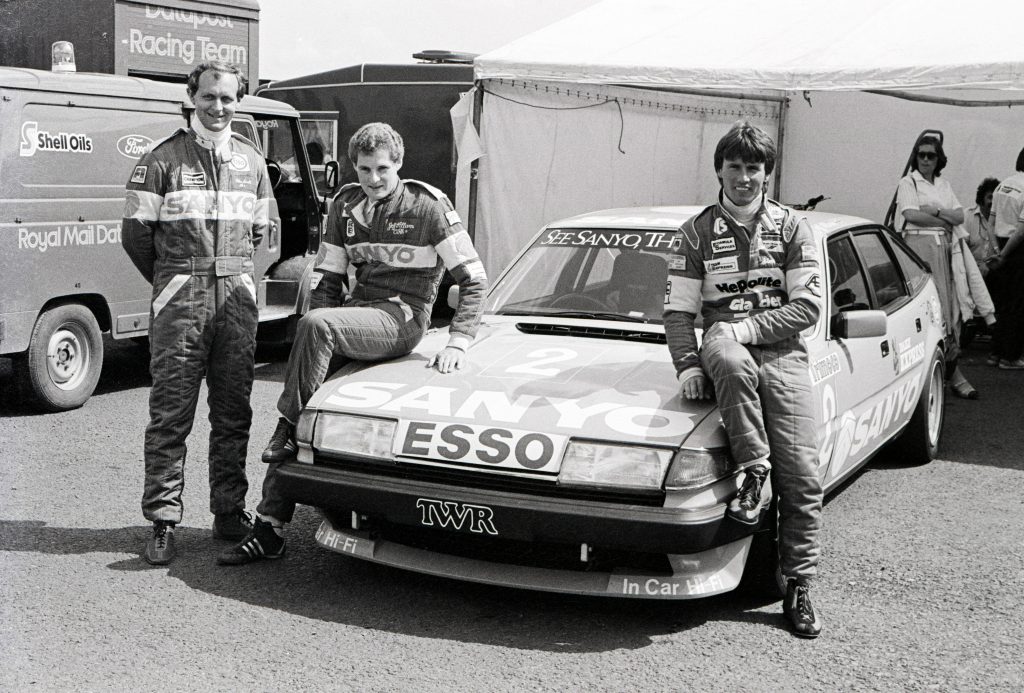

Matters improved when the category’s new kingpin grabbed Rover’s reins for 1981. Burly, tough-minded Scot Tom Walkinshaw and the self-effacing Allam would over the next seven seasons prove that opposites not only attract but also can stick together.

“I’d loved the Capri,” says Allam. “It was so well sorted. The Rover had the power but didn’t handle as well. That changed when Tom got hold of it and put that funny A-frame in the back. Before that, the rear axle had been moving about all over the place.

“Tom knew all the tricks. Once, he had protested our Capri because of an illegal rear rollbar. So we protested his BMW because its trim had been removed. He opened its boot and there was every piece of trim. We got thrown out; he didn’t. He carried the rulebook around like a Reverend with The Bible.”

British Leyland-contracted Allam ended 1981 with a perkier, more reliable Tom Walkinshaw Racing version of the V8, and with three wins on the bounce. He began 1982 with two more victories and ended it as the best of the big class – yet only fourth in the championship. How does he remember that season? “Bloody frustrating!”

Britain had been slow to adopt the freer Group A regulations, preferring to stick with its liberal interpretation of Group 1. That changed in 1983 and, old hat Capri rendered ineligible, the updated Rover Vitesse dominated.

“I still have the notepad-with-pen-on-a-string that we – me, Steve Soper and Pete Lovett – were given telling us who was going to finish first, second and third in the first three races,” says Allam. “No in-house fighting. No knocking each other off the track. But after that we could do what we wanted.”

It was to be a season almost without end, its champion decided by the High Court in July the following year when the Rovers were disqualified because of technical irregularities. TWR attempted to argue that there was such a thing as an Africa market SD1 with larger wheel arches to cope with mud, which led to TWR’s unofficial renaming: Third World Racing.

Walkinshaw was not without sin, but he was a proven winner capable of pulling together deals with numerous manufacturers – sometimes at the same time: he ran Rovers and Jaguars in the 1984 European Touring Car Championship (ETCC).

The Jaguar came in the guise of the 5.3-litre V12 XJ-S coupé. It was not an obvious contender and had proved fast but fragile in 1982 and 1983. By 1984, however, it was the car to beat – and Allam was left disappointed by his mainly Rover gig.

“There were times when I was told to jump in and test the Jag,” he says. “It had enormous power but didn’t stop as well as the Rover or the Capri. If you overdrove it, it could bite. Smooth upchanges were key. Don’t use maximum revs. Glide it through the corners.”

ETCC races tended to be two-driver affairs of 500km, and Allam enjoyed this new challenge: “I love finding a rhythm with a racing car. Given a lap time I could reproduce it for two hours or more. That was my forte.”

He became a pillar of TWR’s effort. Paired with numerous co-drivers, he played expert second fiddle to the number one car of Walkinshaw – co-driven by Win Percy – as Rover fought the turbocharged Volvo 240s in 1985. (Walkinshaw and Jaguar had by now turned their attentions to the Le Mans 24 Hours.)

Allam would, however, have his day in the sun at Silverstone’s RAC Tourist Trophy of 1986. His partner was New Zealand’s Denny Hulme, the 1967 Formula One world champion.

“I was pissed off to be told that I’d be with Denny,” he admits. “I thought he was well past his sell-by date. But then Tom offered me an extra £20,000.

“I was confident all weekend: the car felt good and Denny was competitive. Tom had tried a development engine during practice and not liked it. I asked if we could have it for the race. I think that’s what gave us our advantage.

“I did the first two stints and Denny brought it home. At the press conference they announced Hulme and Allam as the winners – and Denny said, ‘No, it’s Allam and Hulme.’ He became a great friend to my young family.

“For those last two years of its life the Rover received only detailed improvements. The funding was no longer there to develop it. But, big and strong, it was meant for long-distance racing. It was not light to drive – and the early versions didn’t have power steering. In fact, Tom never ran power steering on his car. He never did a day’s exercise in his life but had the stamina and strength to do it. Poor old Win.

“I got to know all its quirks and which switches to press, and when. In ETCC races you couldn’t add oil until a certain time. Well, we needed oil a lot sooner than that. We had a tank inside the engine and, when you got the signal from the pits, you had to switch its pump on and count to 20 while racing at breakneck speed.

“That car was good to me. But if I had to choose…”

Allam got his chance to drive the Jaguar XJ-S at Bathurst in 1985. He qualified on the front row alongside Walkinshaw but paid dearly for a fractional error early in the 1000km race.

“That place is the ultimate,” he says. Praise indeed given that Allam raced at the mighty Nürburgring, the super-fast old Spa-Francorchamps and the barking-bonkers Brno road circuit in what was Czechoslovakia. “Getting on a plane to Australia knowing that you were going to race across The Mountain was a brilliant feeling.

“The Jaguar was some car on that circuit. We were doing 186mph down Conrod Straight – and only we were taking off over its crest. And we were having to brake so hard at the end of it that your bum came out of the seat.

“I had been told to stay behind Tom in the race and was cruising. But Allan Grice, a local hero, was mixing it with us in his Holden Commodore. I just touched him going into a corner. Broken headlight glass went up the air intake and bent a valve.”

His first visit had resulted in a Group A category win – and 12th overall – in a Rover in 1984. His best result, however, would be scored in a Sierra Cosworth RS500 in 1990, at the Bathurst 1000.

“That was difficult to drive,” he says of his first turbocharged touring car. “It had lots of power but sat very upright, very high, on the track. And its floor got so hot that it singed your boots.

“I should have won the 1987 RAC TT in one – the German version of Wolf Racing – with Jo Winkelhock, but it peed with the rain and water flooded the ECU situated in the passenger footwell.

“I drove one of Dick Johnson’s cars at Bathurst in 1989. We were doing 179mph down Conrod, which now had a chicane in it. Normally you drive on the left-hand side because it’s smoother, overtaking on the right. [Team-mate] John Bowe got a tow from me during practice and pulled alongside at 170mph. The next thing the two cars were sucked together and my door mirror was knocked off. He could have killed me. But he just said, ‘Ah, you’ve never had a “Conrod Kiss” before.’”

Allam was sharing another Johnson-run Sierra with New Zealander Paul Radisich in 1990, at the Bathurst race, when a stealthy victory was beginning to look increasingly likely.

“I was about to hand over to Paul when the team came on the radio: ‘Be prepared to push the seat back to its furthest setting. Dick’s getting in.’ Ford wanted a local hero to win.

“F*** that! The seat was adjusted by a little lever and I got my foot under it coming into the pits and bent it. We lost 16sec before Dick realised that he couldn’t fit. He was really angry.

“Paul did his stint and I finished the race [15sec behind the winner]. Driving back to the pits I straightened the handle and it worked perfectly when Dick tried it after the race.

“In truth, we had made one error – going onto intermediate tyres when we thought it might rain – and that additional stop cost us the race.”

Touring cars were by now on the cusp of a major change via the phased arrival of a single-class formula for normally aspirated 2-litre ‘repmobiles’. Conceived in Britain, it would be promoted globally via slickly edited TV packages. Allam was an early convert in a BMW M3, but rough-and-tumble sprint races no longer suited him – though, of course, he would win the 1991 British GP support race, driving a Vauxhall Cavalier.

“When I lost my Vauxhall drive at the end of 1994 I realised that no other manufacturer was going to pick me up because I was by then a Vauxhall dealer,” he says. “I must admit that I had a tear in my eye.

“I’d been professional for 15 seasons. But I would have done it for nothing because I loved it so much.”

Read more

A beginner’s guide to road rallying

The likely lads in a lock-up who made it to the F1 grid

10 starter rally cars that made winners of their drivers