The T-type MG Midget. The pre-war design that triggered the post-war US love affair with British sports cars. The dated machine derided when still in production as late as 1955, yet later loved for its old-fashioned aura. Is a car with such ancient genes a viable classic to own and drive today? And just how alien an experience is owning something with a body frame made of wood and a chassis peppered with myriad greasing points?

Not as alien as you might think, once you’ve reset much of what you’ve learned about vehicle dynamics to date. And owning such a hands-on, analogue, imprecisely hand-made and involvingly mechanical machine is a pleasure of its own. You can’t help but become a bit of an expert, with a better understanding of how the world of artefacts works and how to fix it when it doesn’t. That’s quite empowering.

The story begins in 1936 and the launch of what retrospectively became known as the TA. MG’s Nuffield Group parent had ousted the old MG management and its independent ways, and brought design under central Morris-influenced control. So out went the popular PB Midget with its 939cc overhead-cam engine, in came the similar-looking but longer and wider T-type powered by a more prosaic pushrod engine from a Wolseley, another Nuffield brand.

It was uprated with a pair of Nuffield’s SU carburettors and better breathing, but it was a low-revving, fragile engine with a very long piston stroke. However, its 1292cc capacity was enough to give 50bhp and ultimately more pace than the PB offered, if much less enthusiastically delivered.

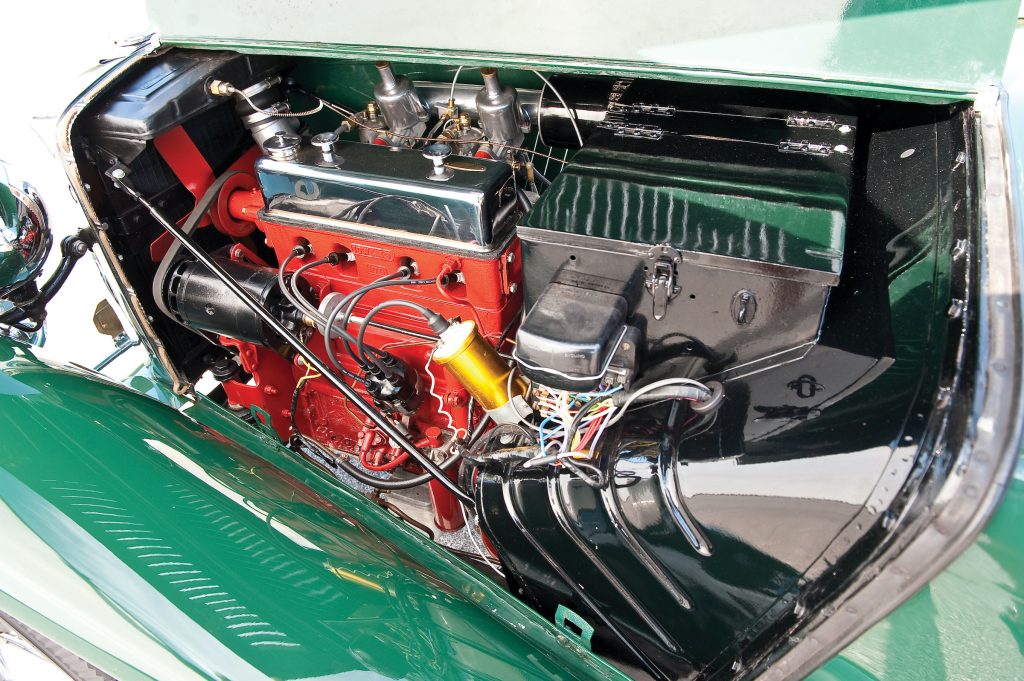

In May 1939 a new and better engine arrived, based on a new Morris Ten motor, still with pushrod-operated valves but featuring a shorter stroke (still very long by modern standards) and a revvier nature with its 54bhp power peak arriving at a racy-for-the-time 5200rpm. This was the 1250cc XPAG motor legendary in MG lore; like other Nuffield engines of the time, it was constructed with nuts and bolts with unusual metric threads despite having standard British bolt heads. This was a strange and rather intriguing legacy from Morris’s post-WW1 purchase of French company Hotchkiss, which had relocated in the UK to escape the Germans.

This new engine, and a conventional dry-plate clutch to replace the old oil-bath unit, together caused the enlivened Midget to be renamed TB. Then WW2 came, and TB production ceased after just 379 cars which makes the model very rare today.

MG’s Abingdon factory wasted no time in getting its sports cars back into production after war ended in 1945, incorporating a few improvements in the process. The cockpit was widened by four inches, the engine gained a hydraulic tensioner for its timing chain, and the troublesome sliding trunnions that located the suspension’s leaf springs were replaced by conventional shackles and rubber bushes. The resulting TC model became a huge US hit much favoured by ex-servicemen who had been in the UK, and 10,000 examples were built – all right-hand drive, despite the Stateside sales.

The enthusiasm was short-lived, as buyers began to crave a touch more civility, a better ride and, in the US, left-hand drive. So in 1949 the new TD Midget arrived with a new, more rigid, box-section chassis adapted from the Y-type saloon. Its three main advances were independent wishbone front suspension instead of the former solid beam axle, rack-and-pinion steering and a rear axle located under the now-upswept chassis rails instead of over straight ones, which allowed more suspension travel.

The whole car was wider, all cars (not just US-market ones) had bumpers, and – shock – the 19in wire wheels gave way to pressed-steel ones of just 15in diameter, albeit with sporting-looking perforations for brake cooling after the first few cars. There was still no fuel gauge, but least a warning light gave notice of impending emptiness. The TD was a great success, with nearly 30,000 examples until the TF – there was no TE – replaced it in 1953.

MG’s designers wanted the replacement to be a much more modern-looking machine but the now-BMC top brass didn’t want competition for the recently-launched Austin Healey 100. Instead, the TD shape was updated with lower bonnet line, a raked-back radiator grille, headlights faired into the front wings, a more sloping tail – and a return to now-optional wire wheels.

There was slightly more power for the engine, now up to 58bhp thanks to more compression and larger carburettors. More came in 1954 when the engine, redesignated XPEG, was bored out to 1466cc for the 63bhp TF 1500.

In 1955, 9602 TFs having been built of which 3400 were 1500s, the T-type line finally ended when MG was at last able to launch the sleek-looking MGA roadster – whose underpinnings were still clearly TF-derived. There’s a later twist to the tale, though.

Naylor Brothers, a long-established MG restorer, built a short series of TFs in the mid-1980s from parts it had reproduced, updating the mechanicals to a British Leyland O-series engine, telescopic dampers and disc front brakes. The resulting TF 1700, the later ones wearing the branding of the Hutson company which took over Naylor in mid-production, was an interesting curio – but, perhaps surprisingly, a genuine TF 1500 is a keener and more sporting drive.

What’s an MG T-type Midget like to drive?

A TA, TB or TC offers the full-on pre-war experience: a restless ride as the chassis twists and the solid axles reach their narrow limits of travel, springy steering, drum brakes that need a good, hard shove, and the need to match your engine revs and gearchange speeds with a degree of mechanical sympathy as you dance with floor-hinged pedals and a roller-pad accelerator.

Soon, though, you’ll make sense of an early Midget’s garrulous messages, learn the required light touch on the giant steering wheel as you accept that the gentle meanderings are largely self-correcting, and enjoy the spirited blare from the twin-carb engine overlaid by the rich, melodic whine from the lower three gears. You become part of the machine.

The TA is the least thrilling because its engine really is not a revver, and attempting to make it so leads to mechanical carnage. Early ones have synchromesh on just the top two gears, too (and no T-types have it on first), so you’ll need to know how to double-declutch. An XPAG-engined car is a lot friskier, and on a fine day with the wind all around you there’s a great sense of being part of the three-dimensional landscape rather than just observing it.

There are no seatbelts, obviously. The doors are hinged at their rear edge, luggage space is meagre (extendible with a luggage rack), the wipers are slow, primitive and have to be parked manually, the view along the bonnet is a vintage-evoking joy. For the real racing look you can fold the windscreen down, but either fit a pair of small aeroscreens or wear goggles. At the opposite extreme of engagement with the environment, there are sidescreens to keep the worst of the weather out provided you’re moving, and a hood as a last resort – but it takes a while to set it up.

These MGs are fast enough not to get in the way on a motorway – they’ll work their way up to 80mph or so – but you’ll enjoy them more on roads from the pre-motorway age. The same applies to the TD and TF, but they instantly feel a lot more modern than their predecessors. The way they move along the road is much more all-of-a-piece, their steering has an up-to-date sense of sharpness and speed of response, their brakes are more powerful and the ride, though still lively, is a whole lot more absorbent.

The final TF 1500 has enough power and torque to mix entirely happily with modern traffic, and both the steering and the ride are significantly better than those of a contemporary Morgan. It’s a proper speedy sports car.

How much do T-type MG Midgets cost?

It’s curious fact that, according to Hagerty’s valuation tool, what seems to be the least appealing T-type, the TA, is worth the most: from £15,000 for a ‘fair’ example to £51,400 for a concours car. An ‘excellent’ one – a car which most people would be very happy with – attracts a £35,900 valuation.

Maybe it’s the attraction of being a pre-war machine, in which case the ultra-rare and better-engined TB should be worth yet more. And it probably is, but there are too few for reliable statistics.

A slightly sad TC is worth an average £13,900, a concours car £46,600; most cars are in the £20k-£30k area. TDs, objectively better but subjectively less appealing with their raffishness watered down, are the bargain T-types with a span from £10,500 (needy) to £35,200 (perfect). You should be able to get a great example for £20,000 or so.

The TF has a stronger personality of its own, and is a fine-looking machine. Values start at £15,000, an excellent car is over £30,000 and the very best pass £40,000. Unsurprisingly, the 1500 version attracts a significant premium, especially at the high end of condition. A fair TF 1500 might cost £15,800, rising to £48,300 – second here only to the TA – for a concours car. Between those extremes, expect to pay an average of £24,500 for a good TF 1500, £35,100 for an excellent one.

What goes wrong, and what should you look for when buying a T-type?

First off: stand back and look at it from all angles. The ash body frame is very likely to have been rebuilt or replaced at some point, and there’s plenty of scope for it not to be quite straight or symmetrical. Looking at the front head-on, does the centre line of the centre-hinged bonnet point exactly to the centre of the car’s tail? Does the scuttle look level relative to the radiator, and does the same apply to the early cars’ front apron below the radiator? Are the door apertures the same length on each side, and do the doors fit properly? If they don’t, is it worn hinges or something more serious?

The steel body panels can rust, of course, but rot in the body-tub wood behind them is more serious. Have a good look at those sections you can get at, mostly the lower longitudinal rails and the uprights at the base of the scuttle and bulkhead structure, and check for softness. In a really bad case, you might be able to wobble the scuttle from side to side. The outer panels are fettled to fit each individual MG, and replacing them will involve much work.

A further check is to make sure the join line between the top of the bonnet and its side panels (the latter fixed and separate from the top panels on TFs, to the detriment of engine accessibility) aligns exactly with the seam on the scuttle section just below the windcreen’s support pillars. If the lines don’t align, something is amiss with the body frame.

The chassis itself is quite strong but cracks can appear, notably on TDs and TFs below the scuttle where the main rails’ box section becomes a channel section. The suspension is similarly robust, but check for play in the kingpins, perished rubber bushes (which will clonk on a test drive if really bad), leaking lever-arm dampers and, in earlier cars with a steering box, excess play on the steering. Up to three inches at the steering wheel’s rim is acceptable, less is much preferable.

With wire wheels, tap the spokes and listen for a consistent ‘twang’ from one spoke to the next, indicating even tensions. A clonk on moving off can be caused by worn splines in the wire wheels’ centres, or in the hubs on which they fit, or both. Whatever the cause, it will need to be fixed.

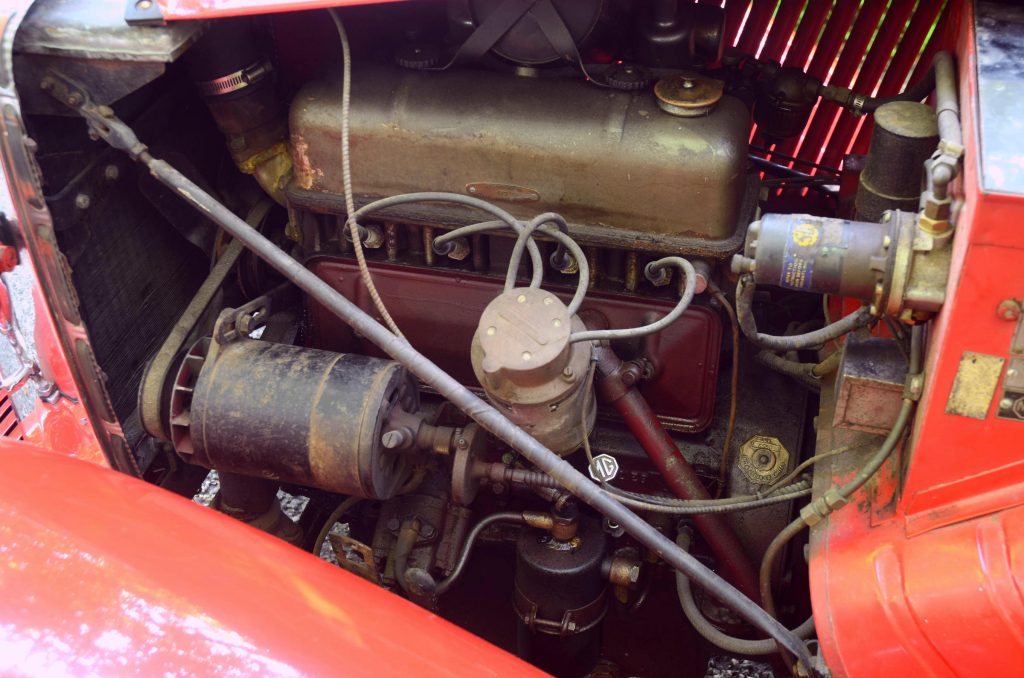

The engine, both XPAG/XPEG and the earlier TA unit, coded MPJG, is straightforward and mostly robust, over-revved MPJGs apart. Usual checks for rattles, smoke and oil pressure (ideally 40psi or over at speed) apply. Some TAs have been retro-fitted with XPAG engines over the years, which makes them less ‘pure’ but a better sports car. The gearchange should be precise and easy provided you don’t rush it, but don’t expect too much from the synchromesh.

The electrical system is simple, primitive even, by modern standards, but check everything works and that the ammeter shows a charge when the engine is running above idle speed. It’s also worth checking that all the weather equipment – hood, sidescreens, tonneau cover if you’re lucky – is present, working and in usable condition.

And check the tyres. Cars like this often spend long periods not being used and might cover few miles, so even if the tyres have plenty of tread they could still be old and griplessly hard. You at least want them to have been made this century.

If the car you’re considering needs work, don’t despair. All T-types are straightforward, simple things, and they are well catered for by specialists and the excellent MG Car Club whose HQ is still at the old Abingdon factory site.

So, which is the right Midget for you?

Much depends on whether you like the pre-war vibe, or you want something with rakish old-Midget looks but a driving tactility recognisably related to modernity. The optimum pre-war experience comes with a TB, but you’re unlikely to find one of those. A TA re-engined with an XPAG is virtually a TB; a purist wouldn’t approve but it sounds to us an ideal remedy for the standard TA’s misjudged motor.

The TC best represents the Midget’s car-cultural significance as the archetypal small British sports car. A TD is a bit of an apology, a bit of a compromise, as reflected in its lower values. And the TF? It’s the best driving machine, especially in 1500 form, and the most usable T-type as well as one of the best-looking. It would be our choice… but a really good TC, offering pre-war charms with under-skin updates, would also be hard to resist.

Read more

Buying Guide: Triumph TR4, TR5 and TR6

11 alternatives to the Jaguar E-Type

Buying Guide: Austin-Healey 100 and 3000

Did not the TA engine come from the then current Morris 10/4 motor, which was described as “akin to a Wolseley engine”?

Think you have over priced the MGTA,. Say 35 for top car MG TB 45 and a MGTC 30.

Only going on what we have managed selling these cars.

Steve Baker MG