The Beetle doesn’t need much of an introduction. After all, Volkswagen built just over 21.5 million of them between 1938 and 2003, albeit not in Germany after 1978 (or 1980 for the cabriolet). What was conceived as transport for the masses under Germany’s National Socialism became the wheeled embodiment of Californian peace and love and a quality benchmark for mass-production machinery. And to think that Britain’s Rootes Group turned down the offer to take over production as the ruins of World War Two were cleared away. A crude car with little appeal, they said. Oops.

Time was when Beetles were legendary for their durability, but time moves on and so do durability standards. Most Beetles you’ll see for sale are from the 1960s and 1970s and rust has had plenty of time to eat away at them, while time and mileage will eventually overcome even an engine as famously understressed as Volkswagen’s air-cooled, low-tune flat-four.

The car was never officially called ‘Beetle’, of course, until Volkswagen itself referred to the new-for-1971 1302 and 1302S models as the ‘Super Beetle’ in its marketing. These, and their 1303 successors with deep, curved windscreens, were either the best and most sophisticated Beetles ever built or a travesty of the original’s purity, depending on your viewpoint; Beetle enthusiasts occupy a world of high passions.

Those passions have meant that, over the years, many Beetles have been modified and customised according to a whole range of cults and subcultures: low-riders, beach buggies, psychedelic paint jobs with flowers on the dashboard, Cal-look, Baja-look and much more. But, as with nearly all classic cars, the examples most prized today are the ones in standard or near-standard spec, perhaps with a few discreet improvements if they are to be driven comfortably in modern conditions.

Most valuable, but least practical, are the original ‘split-rear-window’ cars with a 1131cc, 25bhp engine. By the end of 1953 the rear window was a one-piece oval, and shortly afterwards the engine was up to 1192cc and 30bhp. In 1957 the rear window became larger and squarer, and there was a new dashboard whose basic design endured to the end.

Further incremental increases in all window sizes occurred through the years, while other milestones include a redesigned engine with 34bhp (1961), a 40bhp version enlarged to 1285cc (1965, the year the hubcaps were flattened and the wheels perforated), and for 1967 a 1493cc, 44bhp engine plus disc front brakes and an extra stabiliser spring for the swing-axle rear suspension.

These three engines – 1200, 1300 and 1500 – continued into 1968, the year that saw the Beetle’s biggest visual change. Sloping headlights were out, vertical headlights were in, along with higher-mounted, square-section bumpers with a black indentation across their width. Larger rear lights and a squared-off engine lid continued the modernised look, and all except the basic 1200 models, which continued with the previous low bumpers, finally got 12-volt electrics instead of 6-volt.

The 1971 Super Beetle was something else again, with a bit of a nod to its distant Porsche 911 relative under a skin which included a more bulbous bonnet covering a much larger luggage compartment. Also under that nose, making that deeper boot possible, was a new MacPherson strut front suspension in place of the old transverse torsion bars and paired trailing links. At the back, semi-trailing arms replaced the old swing axles. The 1302S version also got a new 1584cc, 50bhp engine, and all engines except the 1200 now had separate inlet ports for each cylinder instead of siamesed pairs.

Two years later, the 1303 and 1303S added that panoramic windscreen and a new, padded dashboard, all designed to move the scuttle away from the occupants for safety reasons. But these Super Beetles weren’t popular, and by 1975 they were gone apart from the cabriolet version – which ended up being the last German-made Beetle, in 1980. The Golf had arrived in the mid-1970s, Volkswagen’s destiny was heading in a different direction, and most Beetles that were still being made were fairly basic 1200s albeit with the 1968 visual updates and outsize 1303 rear lights.

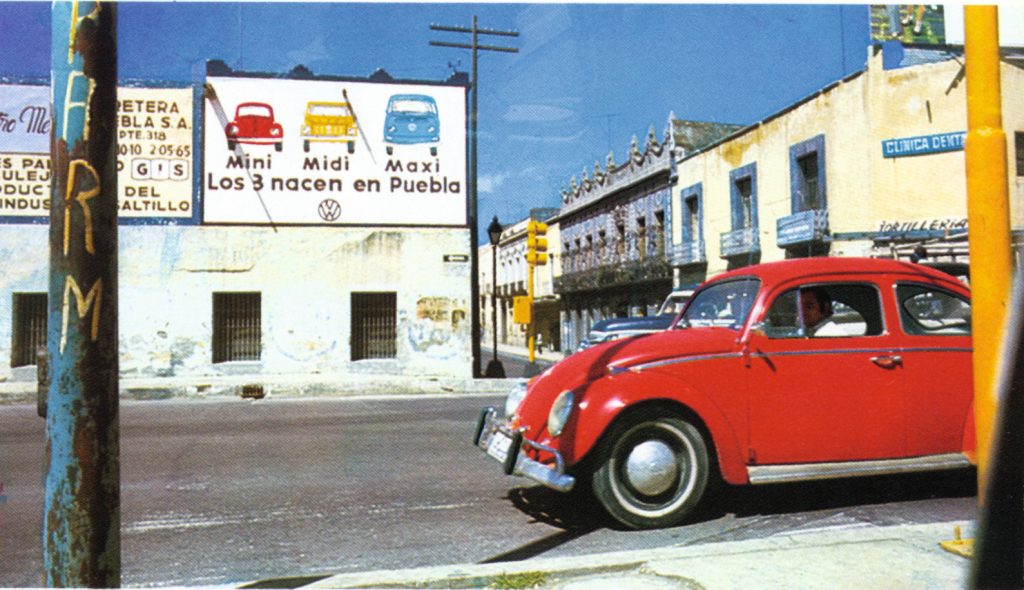

Meanwhile, Latin America continued as the main production source outside Germany, mostly Mexico and Brazil – the former’s factory in Puebla building the last ‘original’ Beetle in July 2003. Some of these cars have made it to the UK. It’s thought that they share just one part with their distant 1131cc ancestor, a small rubber component under the bonnet, but as far as the design philosophy is concerned the thread could hardly be stronger. No other car has ever made it almost into the modern world with so little evolution. Maybe that’s why we still love them so much.

What’s it like to drive?

Ugly, slow, noisy, expensive – that’s what Volkswagen’s own advertisements used to say. True, a Beetle, even a 1303S, is not remotely rapid but it’s designed to be driven flat-out all day. And when you’re cruising, the engine’s happy beat seems to get left further behind you. That flat-four chunter is the Beetle’s aural signature, one of the most recognisable of car sounds.

Your feet press pedals hinged on the floor, and your hands hold a big steering wheel whose action feels springy but positive enough. Light, too, because there’s not much weight over the front wheels. This rearward weight bias can make a Beetle skittish in crosswinds, and you have to remember the tail-heaviness if you need to slow suddenly in a corner. There’s not enough power to get into much trouble, even in the swing-axle cars (which means most Beetles), but a Beetle’s dynamics offer a very different experience from what most people are used to. The Super Beetles feel, and are, more planted on the road, and a 1600 example is the closest you’ll get to the sensation of normality – if that’s what you want.

All Beetles feel solid and well made, with the exception of the gear lever’s springy, clonky action. Frills are mostly absent, but you’ll enjoy the sense of unbreakable simplicity. You can stash a surprising amount of stuff in the space behind the back seat, too.

How much does a Volkswagen Beetle cost?

As you would expect with a car in production for 65 years, Beetle values cover an enormous range as a look at the Hagerty price guide will reveal. An early car, split- or oval-window, could be worth an astonishing £40,000 or more if it’s in concours condition, while a mid-1960s car in smart, usable but not show condition might cost a quarter of that. Just a little more, around £12,000, would buy you a concours 1302S, although the 1303S is a touch more valuable.

You’ll pay more for a cabriolets than for a same-age, same-spec saloon. Using that mid-60s car as an example, a 1200 saloon could cost around £16,200 in excellent condition but a 1200 Cabriolet more like £26,800. The gap isn’t quite as large if you move into the 1970s but does increase for cars in better condition; there may only be a couple of grand between a 1302S saloon and Cabriolet for a condition 3 (good) car, but if you move up to condition 2 (excellent) you’re looking at as much as £10,000 between the two, with cabrios breaching the £20k barrier.

Super Beetles, while being rare, aren’t quite as popular so tend to be valued less than the technically less sophisticated models sold before, and the aforementioned curved-window models are less popular still. The benefit to this is that they’re among the most affordable way into a Volkswagen Beetle despite them being the most usable and powerful, and while there’s again a disparity in values between saloons and drop-tops, it makes the cabrios among the least expensive open-roofed Beetles. The Hagerty Price Guide puts the entry-point to Beetles as a whole at just over £4000, which should get you something usable.

Modified Volkswagens are almost as common as standard examples, with an ardent scene of admirers doing everything from fitting different wheels to transplating the full drivetrain from an early 911. It’s almost impossible to value a modified VW because for every modification there’ll be someone who likes it enough to choose it over a standard car, yet the collector market values the standard and original examples most highly. The Volkswagen is that rare thing in that a modified car needn’t always be worth less than standard, provided the work is to a high standard and you encounter the right buyer when you come to sell.

The upshot is that if you have a five-figure sum to spend, you should be able to buy a very pleasing Beetle.

How much does it cost to service?

Specialist Just Kampers sells full service kits for 1200, 1300, 1500 or 1600cc engines for under £90. This kit includes a set of spark plugs, HT leads, distributor cap, rotor arm, points, oil strainer, oil change gaskets and 5 litres of engine oil, making it a comprehensive kit that contains everything you’ll need to do the job.

Air filters can be had from around £15. As standard there are no fuel filters, but an aftermarket item can be fitted and costs about £1 when bought in bulk. Modern fuel lines can be ethanol resistant, but we’d still use an ethanol inhibitor in the fuel to protect the gaskets inside the carburettor.

Beetles are among the easiest classic cars to service yourself, with nearly everything accessible when the engine cover is open. Aircooled aficionados will delight in telling you the entire engine can be separated from the gearbox and dropped out the bottom of the car in well under an hour once you’ve got the technique down, so you can even service the engine out of the car if you fancy doing so in more comfort. There are numerous specialists who can do it all for you though, with decades of skill behind them and some fairly reasonable price plans.

What goes wrong and what should you look for?

Probably the most important part to keep an eye on is the fanbelt. If it breaks, the hefty air-cooling fan stops and the engine will seize up very shortly afterwards. It’s advisable to carry a spare, plus the tools to separate the two halves of the dynamo pulley so you can fit a new belt. Tension is adjusted by adding and removing shims between these halves, so making the belt sit higher or lower in the pulley’s vee.

With that important caveat covered, we can look at the rest of the engine. Not much of it is visible in the engine bay beyond the fan cowling, the dynamo, the ignition system and the carburettor, because the rest lies beneath the black-painted, pressed-steel ‘tinware’. It’s important that the tinware is all present; if it isn’t, cooling air won’t be directed to the right places and the engine will overheat.

Check if the crankshaft pulley can be moved back and forth; if there’s more than a tiny amount of crankshaft endfloat, there’s heavy wear within. Check that the oil is clean, too, because an air-cooled engine naturally runs hotter than a water-cooled unit and the oil performs a vital cooling function as well as a lubricating one.

Now look underneath the engine. There will probably be signs of oil seepage around the pushrod tubes, which are convoluted to allow for expansion, but beware of drips or excessive wetness. Investigate the state of the exhaust system, too, including the heat-exchanger jackets around the system’s far reaches. Hot air from these warms the cabin, and a smell of exhaust inside the car (dangerous) means there’s an exhaust leak inside one or both exchangers.

That hot air is ducted into the front of the cabin through the sills. Warm air can hold more moisture, which condenses out of the residual air when the car has stopped driving and is cooling down. This leads to rust, especially where the sills join the bulkhead and inner wheelarches inside the cabin. It’s a favourite Beetle rust zone. Another is under the rear seat, where the battery lives, but check the rest of the floorpan too, and also in the base of the stowage area behind the rear seat.

Other rot-spots? The spare-wheel well, along the body where the wings are bolted on and the mounting points for the running boards are all worth inspecting. And then there’s the chassis itself, a separate platform construction to which the body is bolted. Check along its outer edges, under the sills, and also check the ‘frame head’ – the area to which the front suspension is bolted, which can rust at the bottom. If you’re looking at a Super Beetle, also check the top mounting areas for the MacPherson strut front suspension.

To return to the engine, its natural running noise is a slightly metallic beat but rattles from loose or worn valvegear and knocks from bearings are not normal. Don’t assume they are just part of the regular Beetle soundscape. Smoke is bad, too, if it’s more than just the puff of blue on start-up from cold that’s quite common in ‘flat’ engines.

The positive here is that reconditioned engines are readily available, as are the majority of mechanical parts including the braking and suspension systems. Restoring a Volkswagen Beetle is more a case of time and money than sourcing obscure spares these days.

Usual checks for worn suspension joints, leaking driveshaft boots, uneven braking, tired gearbox synchromesh (none on first gear before 1962) and the function of electrical items apply as much to a Beetle as to any other classic car.

So, which is the right Beetle for you?

If you want to be a part of the modified Volkswagen Beetle cult, you might be drawn to a car already lowered and hotted-up. Try it before you buy it: major lowering can bring major handling and ride snags, especially if it has been done on the cheap, while big carburettors and a loud exhaust won’t necessarily add engine power unless the rest of the engine is altered to make use of them. There are many beautifully modified Beetles, but there are also some horrors.

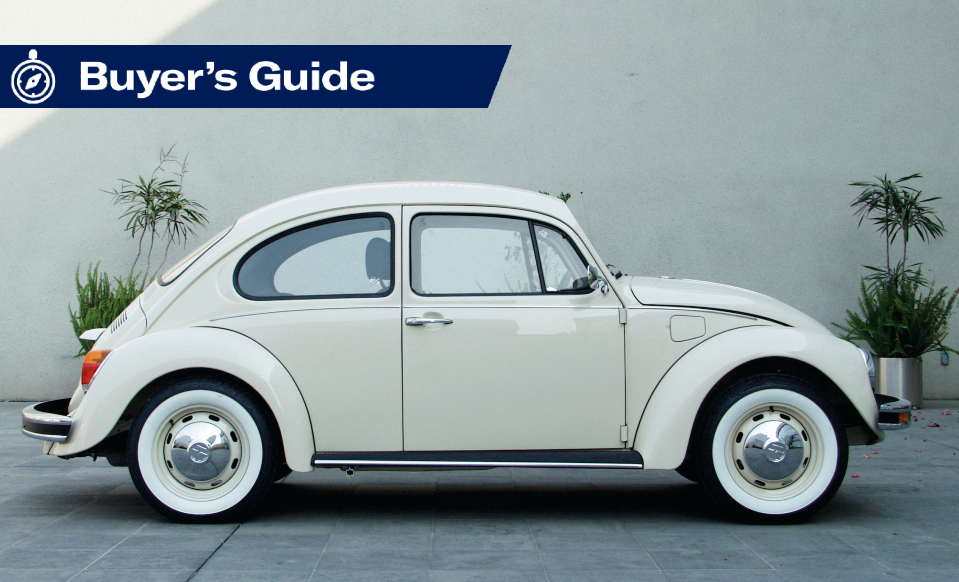

As for which model, that’s your choice. Beetles from 1962 to 1967 are perhaps the best blend of old-school purity with practicality, but the 1968-on cars with raised bumpers and vertical headlights bring a dash of modernity which has aged remarkably well. The rare Super Beetles look a touch awkward with their bulbous bonnets, but they handle better, feel more modern to drive and can be good value. If your heart is set on a mid-1950s oval-window 1200, though, we’d be with you all the way.

Read more

The complete guide to £10,000 starter classics

Hard Craft: Zoe Sadler, author and illustrator

Buying Guide: Morris Minor (1948-1971)

Not a single mention of the GT Beetle aka 1300s.with 1584cc but 1200 body shell with smaller wheels