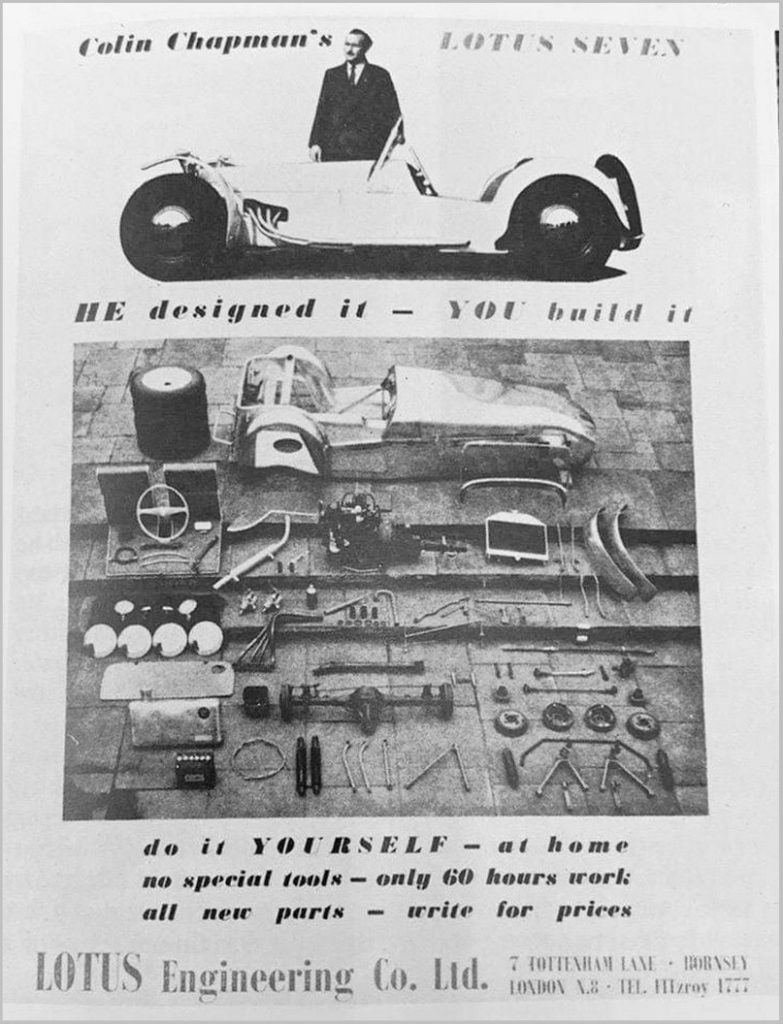

One of the most famous numbers in the classic sports car world very nearly counted for nothing. The Lotus 7 was hastily conceived by Colin Chapman to address the need for a money spinner in order to supplement the income from selling racing cars. The 7 number had been left fallow when a Formula 2 race car project didn’t come about, and it made sense to use this designation because the 7 was a successor to the simple 6 that had been a hit as a clubman’s road and race car.

Chapman is said to have dashed off the design for the 7 and had a base built within a week by Progress Chassis, while the bodywork was made by Williams & Pritchard in aluminium. Rather than the basic 6, the new 7 had a lot more in common with the sleek Eleven, and the five earliest 7s were made with Coventry Climax engines and De Dion rear axles to use in racing. However, the production 7 that went on sale in October 1957 had more humble specification, with a live rear axle and a Ford 1172cc side-valve engine, though Coventry Climax and Austin A Series motors were offered not long after the car was launched.

Cheaper than an Austin-Healey Sprite, the 7 proved popular right from the start and offered plenty of performance, even with the modest 40bhp Ford engine and three-speed gearbox. All of the parts came in a kit, though the factory could also assemble the car for you at extra cost. Most owners chose to build the 7 themselves as this saved the dreaded Purchase Tax levied on new cars in the UK at the time.

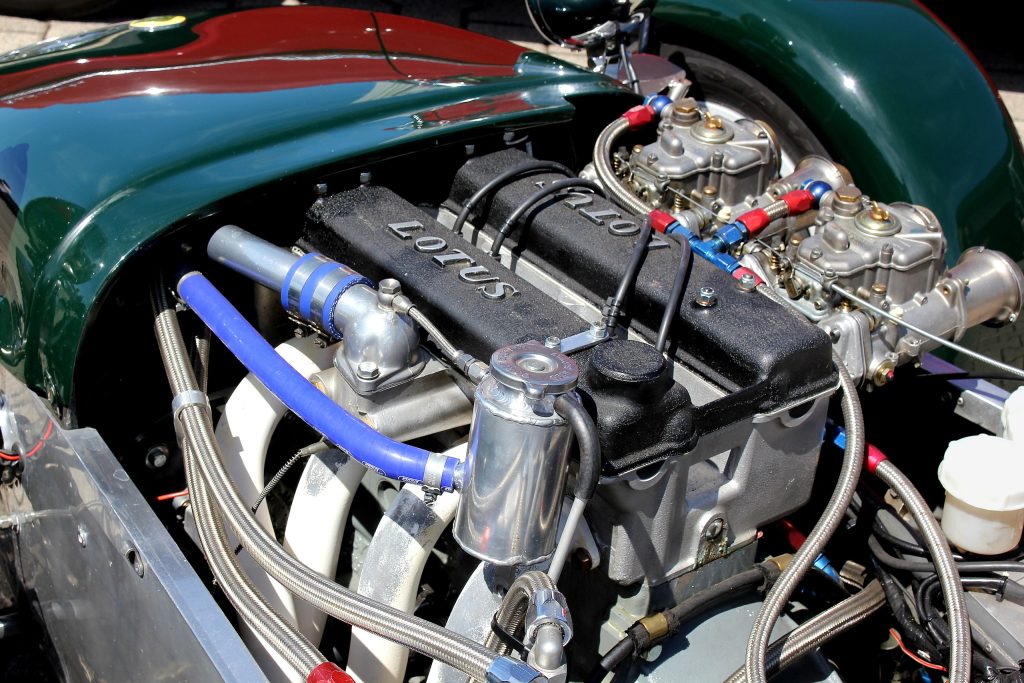

In 1960, a Series 2 version of the 7 arrived, with bodywork that more closely resembles how we imagine a Caterham 7 today. There was a wider range of engines to pick from, including Cosworth-tuned Fords. This was the longest-running version of the 7 during Lotus’ time building the car, and production went on until 1968, when the Series 3 arrived with disc front brakes as standard, a switch to a Ford rear axles, and Ford Crossflow 1.3- and 1.6-litre engines as the default options. A Twin Cam SS model was offered in 1969, but only 13 were built; their Holbay-tuned Lotus-Ford engine produced up to 125bhp.

For 1970, Lotus made what seemed like a radical change in the 7 Series 4, with its broader and more encompassing fibreglass bodywork. At the time, it was a logical next step for the 7 and it sold in decent numbers, with all the same engines as in the S3. However, by 1971, Lotus’ focus on more upmarket models meant the end of the line for the 7 badged as a Lotus, though survival came when Graham Nearn of Caterham Cars bought the rights to the 7. His firm initially carried on making the S4, before returning to the elegant S3 shape that is still in production today.

What’s a 7 like to drive?

It might be a simple formula, but there’s something remarkably sophisticated to the way a Lotus 7 drives. Sure, you get battered by the wind even with side screens fitted, and you can hear the carburettor intake and exhaust growl. But then, this is all part of the 7’s appeal as a sports car pared back to the absolute minimum – and it’s also why it performs far better than the sum of its parts.

Because a 7 only weighs about 500kg, even with its least powerful engine you’re still rewarded with brisk acceleration, and all the other elements of its drive begin to make you smile. The steering is light and direct, and only the very earliest cars used a steering box rather than a more accurate rack-and-pinion set-up. You can guide the 7 by fingertips when cruising, and the feel through the thin-rimmed wheel allows you to place the car precisely in every bend. It also helps here that you can see the front wheels bobbing away up ahead.

Another part of the 7’s charm that quickly earns your respect is the ride quality. It’s a Lotus trait to deliver a supremely comfortable and disarmingly soft ride, rather than the rock hard suspension that some sports cars have. In the lightweight Lotus, it lets the 7 flow with the road even when you encounter bumps or mid-corner dips. All of this means you can use every bit of available grip for acceleration, cornering, and braking. Slowing a 7 is best with disc-brake models, and most cars have these now either from new or with an upgrade.

The cockpit of a 7 is a snug place, whether on your own or with a passenger. Expect to rub shoulders with anyone in the second seat, but you’ll also find decent leg room and comfort. Taller drivers may have to remove some padding from the cushions or take them out altogether, but most people fit in a 7. As for creature comforts, forget it.

What you do find in the 7 is a manual gearbox with a quick, accurate shift in almost every version. The original three-speed transmission with the Ford 1172cc engine was not great but Lotus provided a close-ratio gear set and the option of a four-speed unit. A remote shifter also improved the gearbox. With the later Ford engines, the four-speed ’box is a delight to use thanks to its short action and well-defined pattern. Cars with an A Series engine use the same transmission as found in the Austin-Healey Sprite, which is a good unit, and this gearbox was also attached to any 7 with a Coventry Climax motor.

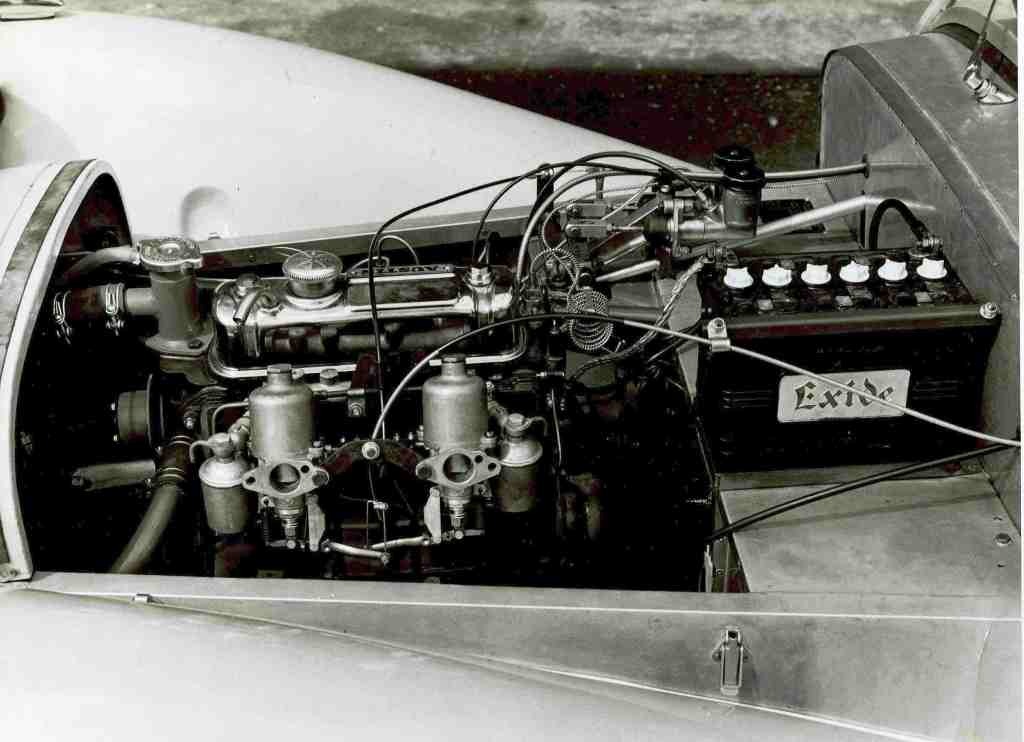

If you’re fortunate enough to own a 7 with the Coventry Climax engine, it’s a very quick car by any standards. The aluminium engine loves to rev and even in a modest tune gives 75bhp. Upping that to 100bhp or more is simple to achieve. The A Series engine is a 948cc unit with 43bhp, which doesn’t sound a lot but feels like plenty as you can work it hard on twisty lanes. Again, tuning this engine is straightforward.

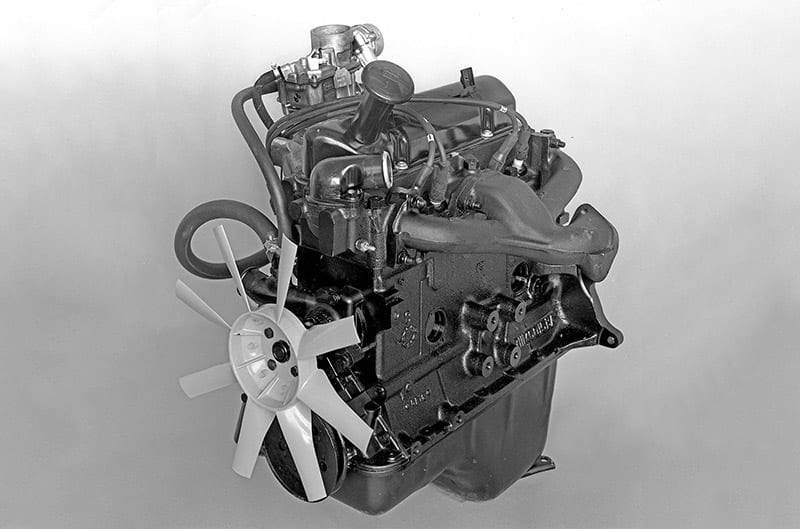

Most Lotus 7 models use the Ford Kent Crossflow engine in 1.3- or 1.6-litre capacities, with as much as 84bhp on tap. Upping that to around 120bhp is no problem, but even in standard form these 7s make rapid progress and sound good doing it. Choose an SS or Series 4 Twin Cam and you have 115bhp to play with from a keenly revvy motor ideally suited to the 7.

How much does a 7 cost?

There are clear divisions in the Lotus 7 market based on age, specification, and rarity. Series 1 cars are highly prized for their looks and simplicity, as well as being the origin of the species, so reckon on paying £50,000 for a very good example and £30,000 for one you can jump in and use without it needing any work. The same values apply to Series 2 cars in similar condition, while the faster Super 7 with Coventry Climax power is at the peak of the 7 hierarchy, with prices around £75,000 for a fine example and more on top for anything with a good period race history.

Lotus made around 1300 Series 2 7s, compared to approximately 340 Series 3s, yet the later S3 is more affordable. Expect to pay £40,000 for the best cars and half that one that is usable but needs some work. With only 13 Twin Cam SS cars out made, expect to pay 50 per cent more for these rarities than for an S3 in similar condition. Make sure any car you look at is what it claims to be, however, as engine swaps and upgrades are common in Lotus 7 circles.

Finally, the Series 4 represents superb value next to other 7s, perhaps thanks to its ugly duckling looks. However, underneath lies the same excellent chassis and drivetrain, so paying £20,500 for an immaculate S4 feels like a bargain. If you don’t mind a car that needs some cosmetic improvement, you can find these for £11,000.

What goes wrong and what should you look for when buying a 7?

Regardless of which Lotus 7 model strikes your fancy, the first thing to check will always be the car’s chassis. Other than the Series 4 model with its more enveloping bodywork, it’s easy to see most of the 7’s chassis by peering over and under the car. Rust will usually be easy to spot, but also have a good look and feel along the bottom tubes, where the aluminium folds under the car and water can get trapped. You should also inspect where the aluminium panels are rivetted to the frame for signs of corrosion.

Aside from rust, the other key point with the chassis is to be certain that it’s straight. Lots of 7s have been used in competition or hard on the road, and many have taken a knock or three as a result. A repaired chassis is nothing to worry about if it’s been done properly on a jig. Take a tape measure and be sure all of the diagonals are true, or have the car inspected by an expert if you’re not confident on this front.

The bodywork of a 7 is a mix of aluminium and fibreglass. Even the best cars are likely to have some very slight ripples in the alloy panels, so best not to worry too much about this as 7s are made to be used. The nosecone is susceptible to parking knocks and the rear wings’ leading edges take a battering from stones thrown up from the front tyres.

Inside the car, be sure the panels all sit snugly to the chassis. There’s little else to concern yourself with in the cockpit of the Lotus, as there just isn’t much more in there. An original steering wheel is good to have, and they can be restored if they’re damaged or worn. Instruments should work and the basic seat trim should all be there. Some cars might have carpet to add a little civility, and these can be replaced if threadbare.

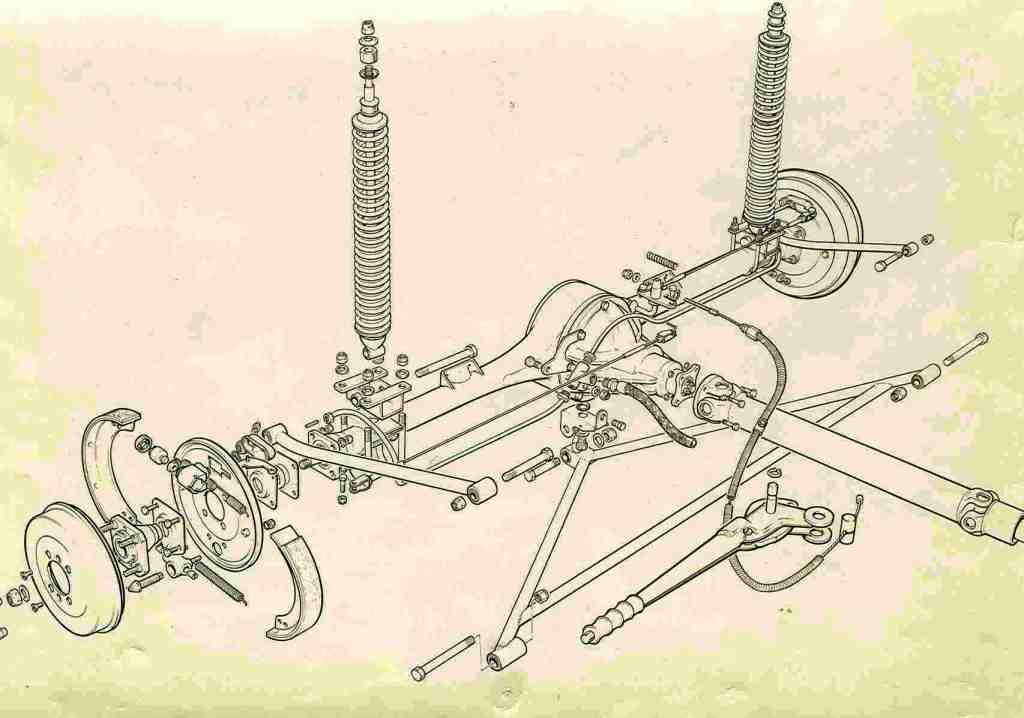

Next port of call is the suspension, steering, and brakes, which are fundamental to how a 7 drives. Only the very first handful of 7s came with a Burman steering box, before the switch to a Morris Minor–derived steering rack. It should turn freely and lightly as soon as the car pulls away. Any slop or play in the steering or suspension is almost certainly due to worn bushings, which are straightforward to replace and within the scope of the home mechanic. The same ease of replacement goes for the brakes, and most 7s have been improved with front discs, if they were not supplied originally.

Ford and Austin gearboxes are reliable, and they are also not expensive to have rebuilt. The rear axle on early cars was from a Nash Metropolitan, while S3 cars and on used a Ford back axle. Thanks to the lightness of the 7, both axles last well and cope with plenty of power.

Lotus offered quite a selection of engines in the 7 during its time building the car. Covering them all here would take too much time, but there is plenty of advice out there for the Ford 1172cc side-valve motors and Kent Crossflow units, as well as the Austin A Series engine. Parts are widely available, along with a huge range of upgrades. The Lotus Twin Cam engine is a bit more exotic, but there are lots of Lotus specialists who can rebuild or supply parts for this engine, as it was also used in the Elan and Europa. Then there’s the Coventry Climax engine, which will require careful inspection by a specialist before buying a 7. Luckily, this engine is used in a variety of performance cars from the same period as the 7, so there’s a good network of parts suppliers and improvements on offer.

Which is the right 7 for you?

The charm of an early Lotus 7 is undeniable, especially if you’re lucky enough to find a Super 7 with the Coventry Climax motor. These Series 1 cars are thin on the ground, though, so a Series 2 with the Ford 1500 engine is a better bet for most needs and comes with an added dose of performance thanks to its 66bhp in standard trim. Don’t be put off if you find an S2 with an uprated engine, as it will deliver a great drive coupled to the earlier, more delicate looks. This is where we’d aim to spend our money.

For some, the S3 is the pinnacle of Lotus 7 production. It has the looks we recognise in the Caterham 7 allied to Ford’s dependable and very tuneable 1.3- and 1.6-litre Crossflow engines from the Escort. Many have been upgraded for more power, and 130bhp is on the cards without spending a fortune to create a very rapid 7 for road, track, and even competition use.

Lastly, don’t discount the Series 4 7. Yes, the styling isn’t to all tastes, but it is a great value slice of 1970s design, and it’s a marginally more practical car than its earlier siblings.

I’ve owned the red S2 in the 6s and 7s photo since 1974, and found this article interesting. However the main gap in potential problems is the S2 axle which has always been a weak point! The Standard 8/10 axle is light but not designed to take suspension loading in the way Mr Chapman thought up with the A frame mounting under the diff. Most S2s cracked their axle casing and will have had some method used to reinforce them. Alternatively different stronger/heavier axles can be fitted but these usually increase the track so that wider rear wings have to be fitted making the car look like an S3 or early Caterham.

Last comment, if you can get a 7 and use it!

Very concise intro to anyone thinking of owning a “7”.

Hi,

I bought a kit in 1976 as I was too late to purchase one of the 12 Lotus 7S models fitted with the Holbay CFR 1600 crossflow, however I bought a brand new Holbay CFR 1600, and a Lotus sprint gearbox, and built a 13th Lotus 7S what would be a ballpark valuation

I purchased an S2. I will be taking possession of it soon. The car is immaculate, owned by my former employer who had it in his collection and never drove it. I have dreamt about this car.

What’s your opinion on putting a Honda K20A or K24 paired with a BMW Getrag 5 speed gearbox from an E36? I have collected these parts and I am excited for your feedback.