Sixten Sason is one of the unsung heroes of mid-20th century car design. While the likes of Alec Issigonis and William Lyons are rightly feted, Sason is little known outside of his native Sweden, yet he was responsible for Saab’s first cars and the unique direction the company took throughout its lifetime.

Using his background in art and engineering, Sason designed aircraft before moving on to cars, and he applied the same focus on aerodynamics and efficiency to the original 92 – and to the 96 range that arrived in 1960.

The 96 took Saab from the periphery of the automotive world toward, if not the mainstream, at least a greater acceptance by a wider audience. More cabin space and practicality made the 96 saloon and its 95 estate counterpart brilliant small family cars, when most other carmakers were still turning out three-box saloons.

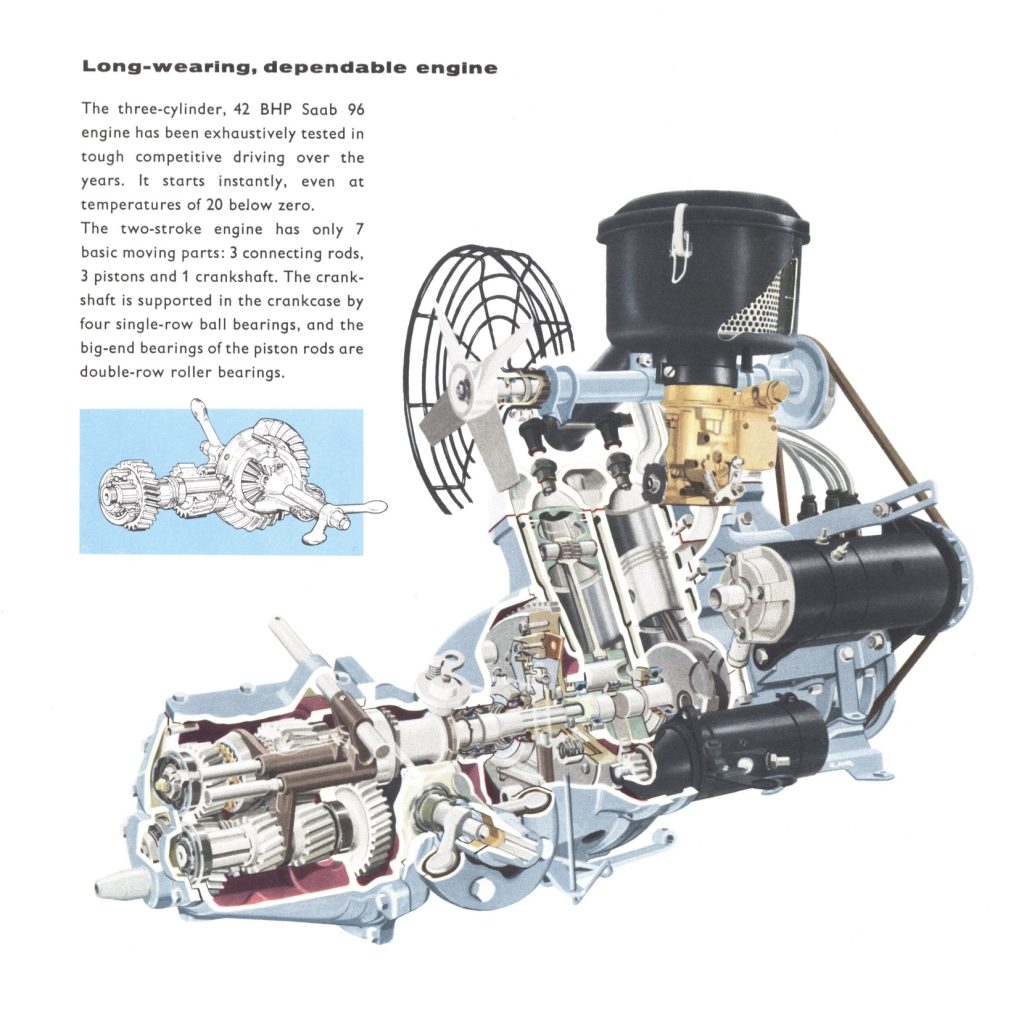

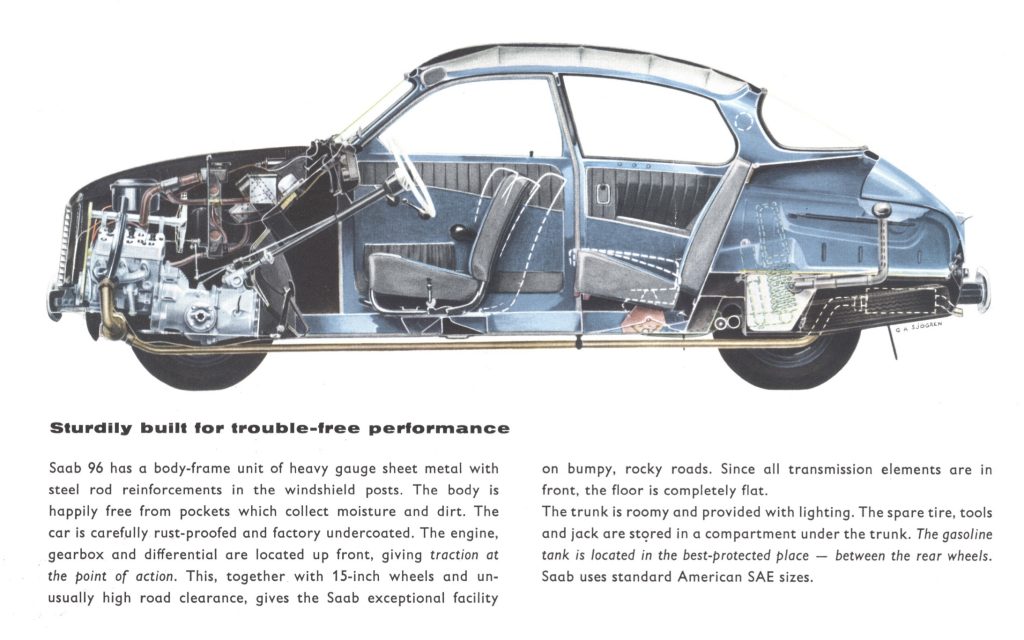

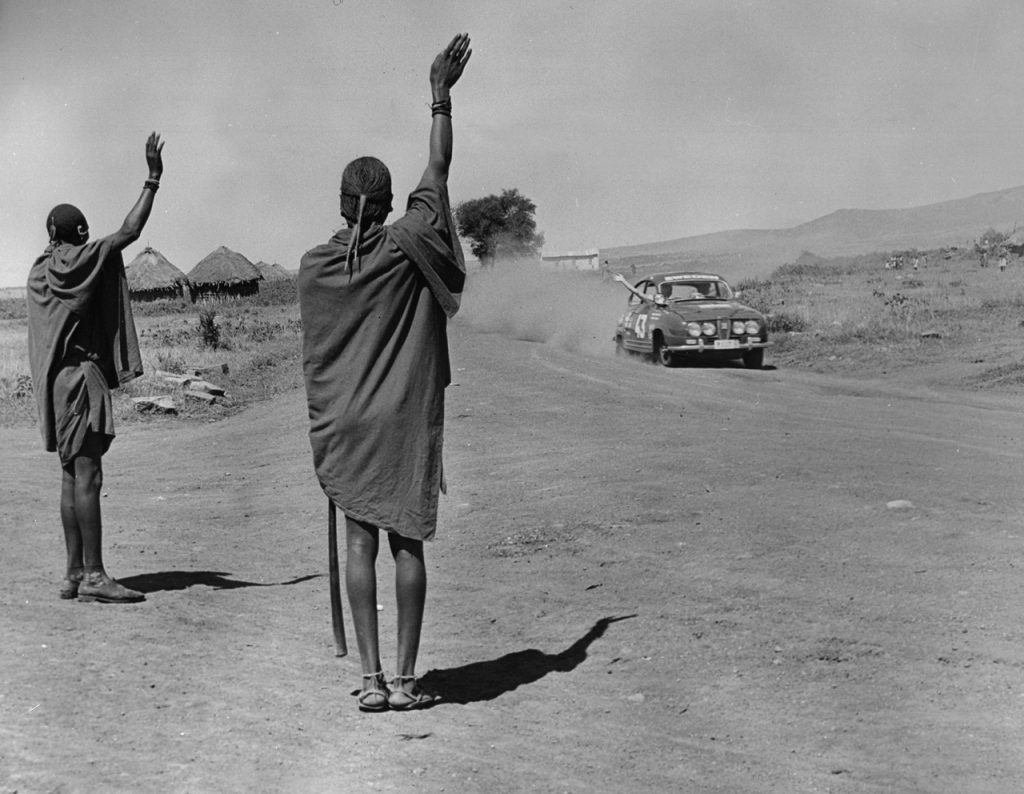

There was still room for unconventional thinking with the Saab 96, and this was evident in its three-cylinder, two-stroke engine. If that wasn’t unusual enough, the engine was mounted longitudinally ahead of the gearbox and drove the front wheels. To some, this seemed wilfully odd, but in Sweden it made perfect sense, as it put the majority of the car’s weight over the driven wheels for better traction in snowy conditions. Tough Scandinavian driving also meant the 96 was engineered for robustness and made from high quality steel rather than inferior materials in an effort to save every ounce of weight.

Saab also gently updated the 96 to incorporate improvements as the years went by, with advances such as improved cooling for 1965 and a four-speed gearbox and more powerful triple-carburetted engine in 1966. The 96 also featured a freewheel because of its two-stroke engine. It was effectively a roller clutch that, when activated by letting off the throttle would allow engine to idle and the car to coast. Without the freewheel, the engine would have been liable to seizing on long downhill stretches when the motor might be starved of lubrication contained in its petrol mix.

The biggest change of all for the 96 came in 1967, when the two-stroke gave way to a Ford-sourced 1.5-litre V4. Saab had tried other engines, but the Cologne V4 offered the best balance of power, economy, reliability, and cost. This four-stroke engine was not universally embraced by existing Saab customers at first, but it soon won over buyers with its greatly improved performance, which offered 0–60mph in 16 seconds as opposed to the 23 seconds mustered by the 841cc two-stroke.

Saab saw no reason to change the mechanical package of the 96 for the remainder of its long production life, which lasted up to 1980. The car even retained the freewheel as a hangover from the earlier variant. There were styling changes, however, such as the switch from round headlights to rectangular items in 1969 and bigger bumpers in 1973. The 96 was also the first car to be offered with electrically heated seats from the factory, in 1972.

When the last 96 was built at Valmet’s factory in Finland, Saab had produced around 329,000 of them, plus a further 78,500 of the 95 estates. Due to its immensely strong build and simple mechanical parts, plenty are still in use today, and it’s also popular as a classic rally car. All of which makes the 96 an affordable choice and huge fun to drive.

What’s a 96 like to drive?

The 96’s driving experience is largely dictated by which engine you decide is the one to have. Pick the two-stroke and the Saab feels like a busy, buzzy car that needs to be worked hard to give its best. With the V4, it’s a surprisingly relaxed machine with a long gait suited to covering plenty of miles.

Starting with the two-stroke triple, the moment it fires up you know this is going to be a different drive compared to almost any contemporary family car. It’s not quick off the mark, taking around 26 seconds to reach 60mph, and you need to hang on to the revs to achieve this sort of acceleration, but so much of the fun of this 96 is in making the most of the motor. As a triple, it sounds fantastic with the added rip of two-stroke power thrown in. You also get used to the column shift and freewheel set-up, which offers quieter moments when the car is coasting.

Switch into the four-stroke V4-powered Saab 96 and you enter a world of much less engine noise, though refinement is similar as the Ford-sourced engine has an offbeat noise all its own. It makes less noise under acceleration than the two-stroke, and the V4 is noticeably quicker to accelerate. Again, the freewheel function takes some recalibration to use to its best, and it also allows for clutchless gearchanges. However, the overriding impression is the V4 model is a car capable of covering plenty of miles in an easy-going manner. Like all 96s, there’s little wind noise thanks to the car’s teardrop shape, while road noise is also a distant hum from the Saab’s narrow tyres.

With the engine mounted well ahead of the front axle, you might expect the Saab to handle with big dollops of understeer. However, the soft-set suspension that does a great job of rolling over bumps also keeps the front wheels on line and biting into the tarmac. It feels like a more grown-up Citroën 2CV in the way the body leans but the car stays faithful to its intended line through a corner, so you can hustle the 96 more quickly than you might think. Little wonder the Saab proved to be a very effective rally car in its heyday. The drum brakes of earlier cars are fine, but later cars with front discs offer more confidence in modern traffic.

Inside the 96, there’s plenty of space for a family of four, plus a generous boot to stash a weekend’s luggage. The 95 estate can seat up to seven thanks to the optional rear-facing seat in the boot, though it might be viewed as more of a novelty nowadays given how close it places anyone using it to the rear of the car in a collision. On the plus side, Saab fitted three-point seat belts to these cars.

How much does a 96 cost?

As later Saabs are climbing in value, particularly the Turbo models, the 96 range has thankfully remained constant in its prices. There’s no great premium for the earlier two-stroke models in the UK market, as some buyers want them just as much as others would rather avoid them. As a result, a clean, tidy, and usable early 96 will cost around £6000. For something in excellent show state, reckon on spending £11,000, though rarities such as the Sport or Monte Carlo versions will push that number up significantly.

A 96 V4 that’s ready to be used and enjoyed regularly will fetch around £6500. An immaculate example comes in around £12,000, though concours cars can make more still. There’s no premium for the 95 estate even though it’s rarer as, again, personal taste in styling plays a part in which Saab buyers want to own.

What goes wrong and what should you look for when buying a 96?

Saab built the 96 to withstand the rigours of a Swedish winter, but that doesn’t mean the car won’t rot with the best of them. With your keen eye on corrosion, start with the obvious outer panels and around the front and rear screen frames. From there, move to inspecting the passenger and boot floors, and the front bulkhead, where blocked drain holes can allow rust to take hold out of sight. Rear inner wheel arches need to be looked at closely, along with the suspension mounts and, finally, the front valance that is prone to chips and dents.

While having a good look around the bodywork, make sure the interior is complete, especially on earlier cars, where trim can be much harder to source. The electrics of the Saab are simple, so if they’re not working properly it should be straightforward to troubleshoot any issues. The same applies to the brakes, suspension, and steering, which are all easy to work on.

Gearboxes, on the other hand, need close inspection, as the earlier three-speeder should have its oil changed every 6000 miles. If not, the freewheel is usually the first thing to stop working and you’ll hear a whirring noise. From 1974 on, Saab used a stronger transmission, and many early two-strokes have been converted from three- to four-speed ’boxes with no ill effect on their value.

Moving on to the engines, the two-stroke triple has only seven moving parts, which makes it very robust, but it must be run with the correct fuel and oil mixture. It also must be stored carefully if left for longer periods, as it will rust internally. Note that parts for the two-stroke are harder to source than those for the four-stroke V4.

With the V4 motor, listen for any rumbling from the bottom end, which points to worn main bearings. The fibre balance shaft gear can also wear and cause vibrations; try moving the fan belt pulley up and down, as any movement here points to excessive wear. Another V4 point to note is that the original Ford carburettor is not great, so many owners swap to an aftermarket set-up. As a result, don’t be surprised to see a Weber carb atop the engine. Have a look at the water pump for leaks and check the cooling system when the engine is warm to make sure it’s working properly, as it’s susceptible to the radiator getting blocked.

Which is the right 96 for you?

The two-stroke triple-powered Saab 96 has long enjoyed a following thanks to its left-field design and revvy engine. This motor lends it a sporting feel, helped by its history in rallying and popularity in historic motorsport circles. Purists will also prefer the cleaner lines of the early 96 and 95 estate models with their shorter noses. However, keeping these two-stroke cars on the road takes more work and time finding parts, and you need to be prepared to work to get the best from them.

As an all-round family classic car that is more than capable of being used in all weathers, the 96 V4 is hard to beat. It feels at home amid modern traffic, as it has just enough performance to parley on busy roads when you’ve got the hang of the column-mounted gear shift and freewheel system. The V4 engine has good low-down torque and can also be tuned for added oomph while still offering 30mpg economy. This is the Saab 96 we’d pick, and it may well prove to be a gateway to the earlier models once you become accustomed to the Saab way of doing things.

It’s a nice review , worth noting that UK Rhd models fetch higher prices and as an owner can say that balance is way better on the 2 stroke , the Ford motor has power but way heavier and affects handling of the car, can sway at 60+

Driving the 2 stroke hard does not hurt, as you point out modern 2T oils at 40/1 ratio are more than enough.

A great wee car very well described here.

I thought this car had aluminium panels so was surprised you mentioned corrosion points. Was I wrong, mine never had rust (that I could see)