Tyger, tyger, burning bright

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

-William Blake

In the spring of 1963, two Englishmen met in a small back room at Shelby American. One was Ian Garrad, a rising star in the Rootes Group organisation, recently appointed the manager of West Coast sales. The other was Ken Miles, one of the best-known racing drivers in Southern California. Both looked over the little British sports car sitting before them, a white Sunbeam Alpine like the one Miles had just campaigned in the previous SCCA season. When they exited the room, it was with a plan to unleash an animal.

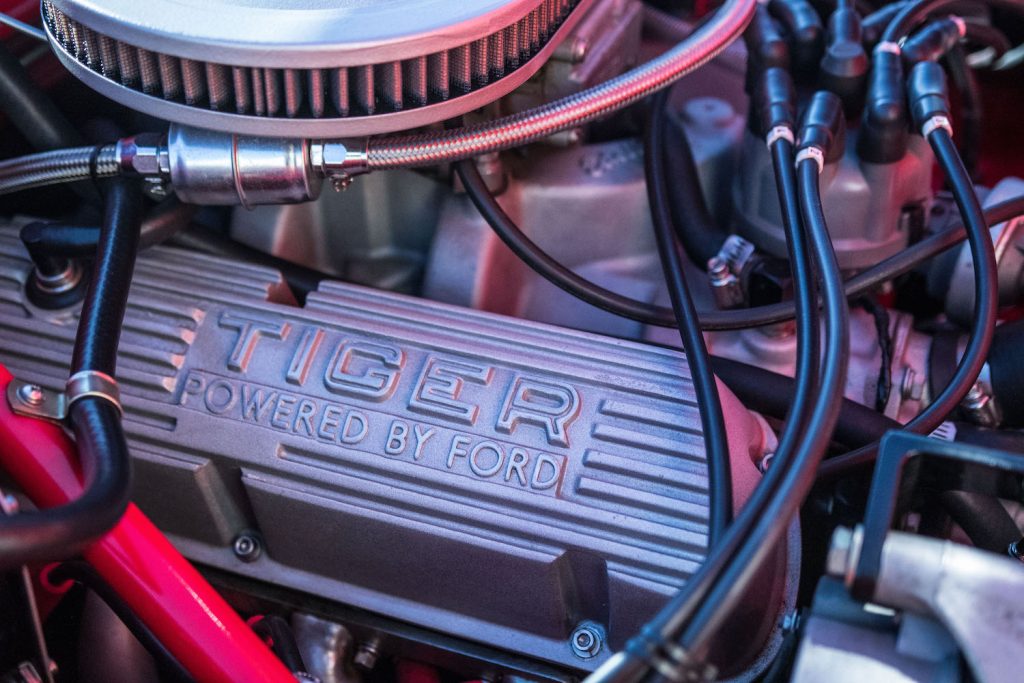

Days later, the two hurtled down a rainy Los Angeles highway in a Frankenstein’s monster of a machine. Their creation was something of a deathtrap – a 260-cubic-inch Ford V8 barely crammed into a roadster that was only ever supposed to come with half that cylinder count. The V8 was mated to a two-speed automatic transmission, and, according to Garrad, Miles had only managed to stuff in the Ford V8 using a modified crossmember and flat distributor from a marine application.

This was the first Sunbeam Tiger, and it was a bit of an Island of Dr. Moreau monstrosity. The weight was too far forward, and the torque stripped the hubs right out of the delicate wire wheels. But it worked. Miles swapped in a set of Minilite alloy wheels, and Garrad paid $400 to have the car sprayed bright red. That prototype now resides in Calgary, Alberta, in the Fred Phillips collection. Phillips reports that it drives a bit crudely compared to a well-sorted production Tiger but works perfectly well as a proof of concept. After it was sold, the prototype Tiger would go on to have a long career as a competitive drag racer in the hands of its second owner.

And it was the blueprint for the car you see in these photos, Alan Rees’ 1964 Mk 1 Tiger. Certified by the notoriously strict Sunbeam Tiger Owners Association, it’s a well-kept machine that bursts to life this morning with a very un-British V8 growl. Tigers are quite valuable these days, and their high values often prompt less-scrupulous sorts to V8-swap an Alpine and pass it off as the real thing. You can spot the genuine article by the flat-mounted rear spare tyre (Alpines had vertically mounted spares), 90-degree exhaust hangers under the car, and some authentically period-correct sloppy stick-welding under the hood.

Rees warms the car up, double-checks the oil level, and off we go in a cloud of V8 thunder. He restored his Tiger 20 years ago and has driven it from his home in Richmond, British Columbia, as far south as Colorado and Southern California. It’s roomier than the big Austin-Healeys he’s had in the past, and the readily available V8 torque makes short work of long-distance drives through mountain passes.

Elegant and muscular, the diminutive Tiger is somewhere between a ballerina and a kickboxer. This early production version is exactly what Garrad had in mind when he initially contracted Carroll Shelby to build a V8-powered Sunbeam sometime in March of 1963.

In the film Ford v Ferrari, the Shelby and Miles story received the silver screen treatment for the pair’s history-making efforts at Le Mans in 1966; as with any Hollywood story, there’s a bit of artistic licence taken and a few inconvenient facts left on the cutting room floor. However, with the Sunbeam Tiger we can find the genuine roots of the partnership between these two larger-than-life characters. Miles wouldn’t just build the first proof-of-concept Tiger, he’d also be involved with developing the breed as he became increasingly involved with Shelby American and its racing efforts.

Initially, Garrad had agreed to pay Shelby $10,000 to come up with a V8-powered version of the Sunbeam Alpine. The money had been scrounged out of the advertising funds with the help of Brian Rootes, son of the company’s owner Sir William Rootes. Sir William was kept in the dark during development and was allegedly quite grumpy when he found out what his employees had been scheming.

Secrecy wasn’t the main problem, however. The principal issue was that Shelby American was stretched thin working on larger projects. That $10,000 from Rootes was essentially chicken feed compared to selling both road- and race-going Cobras, and Carroll Shelby wasn’t in the chicken ranching business anymore. Shelby suggested it would take eight weeks to three months to complete the project, and Garrad knew a feasibility prototype needed to come sooner. That Miles had raced an Alpine was a happy coincidence, but his past skill in building successful MG-based specials like the “Flying Shingle” showed that he wasn’t just a racing driver. He was a skilled engineer and fabricator, too. He would work cheap, as well – Garrad paid Miles just $800 for the swap.

Any crudeness in that first Tiger was due to haste, rather than lack of ability. The second prototype, built in-house at Shelby American, was a more finished effort. It featured rack-and-pinion steering, an engine that sat farther back in the chassis, and a host of other adaptations. The total bill came to $8700, and Shelby was later paid a royalty for every Tiger sold.

Soon, each Thunderbolt (as the first Tigers were known) was lapping at Riverside Raceway with Ken Miles at the wheel to sort out the suspension. Unlike production Tigers, the Shelby prototype had a single exhaust pipe to fool onlookers. The team was also careful never to open the hood around strangers. After a reported 5000 miles of testing, Shelby’s Tiger was shipped to England in the hold of a Japanese fruit freighter.

The Tiger’s arrival at the somewhat repressed Rootes corporate offices set the cat amongst the pigeons. Executive after executive had a go at the V8-powered roadster, returning with fixed grins and tousled hair. Eventually, Lord Rootes emerged to have a go. The best-known story has him accidentally driving the car with the handbrake on, and still being impressed by the power and acceleration. A better version of the tale has the old boy instructing his chauffeur to follow in a Humber limousine should this American-engineered hodgepodge break down, and then promptly haring off across the landscape with such speed that the chauffeur lost him.

Whatever the case, the Tiger made an impression. Rootes ordered the V8 engines and transmissions from Ford, had Pressed Steel provide the bodies, and contracted Jensen for assembly. The Tiger would have an American heart, but it would be built in Britain.

September of 1964 witnessed Miles at the wheel of a Tiger again, this time racing in an SCCA event at Road America. Normally, he’d have run under the number 50, but this time there was a 74 on the Tiger’s door for co-driver Don Sesslar. Since he’d been injured in a crash during practice, Sesslar had to sit out, and Miles drove the whole race. He won his B-production class and finished second overall to an AC Cobra.

That’s how many people view the Sunbeam Tiger: as a runner-up to the better-known Cobra. Likewise, the Ford v Ferrari movie was the first time many in mainstream culture had heard the name Ken Miles. The truth is that both are worthy of even greater widespread notoriety. Ken Miles was a legend. The Tiger he helped create remains a timeless, untamed delight.

Awesome