How’s this for a docu-drama pitch? In the early 1970s, a former builder-turned-yachtsman decides to build his own car, following years of success trialling, auto crossing and racing, beating the likes of Colin Chapman and Graham Hill over the valleys and berms of England.

He creates the chassis and body himself from scratch, investing considerable means in bespoke aluminium fittings, badges and custom-made glass, from Triplex. Motorsport contacts help him design a stainless-steel chassis; factory space and materials allow him to create moulds for a fibreglass body to bring his vision to life.

With the car nearing completion, a break-in sees the plans and moulds disappear into the night. All that remains is the car, named ‘Furia’ after an Italian friend suggested it for ‘fast and powerful’. It is moved to his home workshop, completed after a protracted build, and tested successfully at Brands Hatch in Kent.

Then… nothing. For two decades, the Furia is confined to a garage, owing to a mechanical fault. Then the floor space is needed, so out the Furia goes, enduring the elements for decades to come, effectively abandoned by its creator and forever hidden from the public eye.

We spool forward again, to when the term ‘barn find’ has acquired meaning; the Furia is ‘rediscovered’ by chance and splashed all over the internet, its context forgotten, its identity debated.

By 2020, its creator, spared the misery of lockdown, passes away, leaving a legacy barely known outside of trialling and autocross circles. Wanting to do right by the Furia, his family entrust its remains to a famous British restorer and manufacturer of cars, knowing it will be brought back to its former glory.

It’s a story with hope, peril, and a happy ending – and it all took place in a small corner of Northamptonshire in the Seventies, away from prying eyes.

Sabotage and suspicions: The story of the Furia GT

Donald Rawlings, a joiner by trade, had a successful building firm by the beginning of the ’70s, specialising in three-bed bungalows, many of which still stand across Northamptonshire. An avid trials driver and car enthusiast, he had spent the Sixties at the top of that discipline’s leader board, winning Best Midlands Competitor during the 1964 RAC Trials Championship, and placing highly in the challenging Roy Fedden Trophy Trial, devised by the Bristol Motor Cycle and Light Car Club.

So serious was Don that renowned car constructor, Frank Pryor, built him a trials car to take on the Dellows and Cannons – a special with pivoting transverse leaf front suspension, known as the Nymph. A transaxle, Lotus-wheeled autocross car, the Nymph II, followed, alongside competition entries in a Lotus 7, towed behind the family Aston Martin DB4 Series 2. Happily, both the Nymph and DB4 survive.

The Furia is also still with us, albeit in a significantly poorer state than when it was completed – having sat outside for 32 years.

Don, known to many as Joe, had a string of Aston Martins and Mercedes-Benz SLs as road cars. “He was building bungalows for £2500 to £3000, and buying brand-new Aston Martins for £5–£6000,” Don’s son, Matt Edmonds, tells Hagerty.

With Rawlings Builders sold, Don turned his passion for yachting and boat building into a new business, creating SS Spars Limited, an aluminium fittings manufacturer, specialising in masts of the same material. He built a 20,000 square foot factory in Irthlingborough, Northamptonshire, having moved from a smaller plant in Rushden. His expertise in fibreglass came from the SS Spars days: his pre-Furia project was a 70-foot ocean-going yacht, known as ‘Quintana’, transported across Cardington Airfield (now Cardington Studios) to avoid the bridges on the roads to Poole. Don was, ironically, a master at getting things done.

With the means to buy any car he saw fit, the Furia was another self-made challenge. “He built the car a) because he could and b) because he wanted to,” Matt says. “It was a bit like the yacht – he brought in his cabinet-making and joinery skills, and all the fittings in the yacht were bespoke. He’d always built cars and tinkered, he had that motorsport background, he trialled against the likes of Colin Chapman and Graham Hill, and would bring it up at dinner parties that he’d thrashed Colin Chapman ‘because I had the inside track and could feather the throttle better than he could.’”

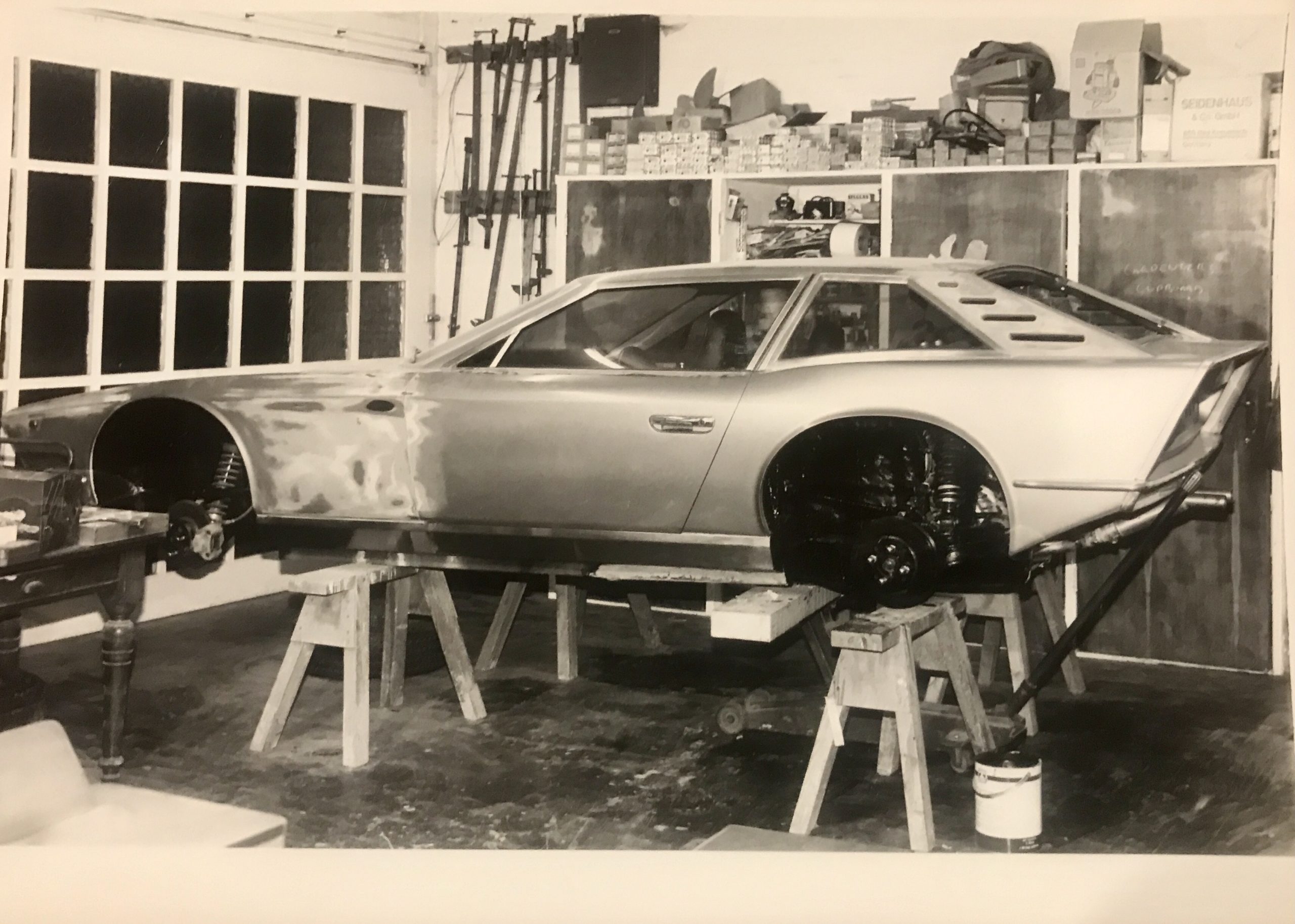

Don had previously fettled his trials and autocross cars at his builders’ premises in Rushden, but, during the early days of the three-year Furia project, the car was thought to have been worked on in Irthlingborough, with the stainless steel chassis, to his own design, welded up by a local firm. Inspired by his earlier, mid-engined Nymph II, the Furia combined the best of both worlds: a sporting engine/powerpack layout, and an automatic gearbox. Many of Don’s cars, particularly the SLs, were self-shifters, and the Furia, intended for road use, reflected a long-term ambition that was never realised. Matt suspects that another trialling stalwart, Bertie Sayers, had a hand in the Furia’s chassis. Sayers’ cars were highly sought after, and the pair became friends, caravan touring across the country.

SS Spars’ foundry cast the phosphor-bronze wing badges, wheel caps, and steering wheel boss, the ‘F’ of Furia used as a motif around the car, its resemblance to the Pininfarina, Fissore or Frua ‘F’ regarded as intentional.

Custom glass was ordered from Triplex, at great expense. One of Don’s last building apprentices, Paul Stanton, who helped build the family home and vineyard, told Matt that “he remembered Dad ringing up Triplex (now part of Pilkington) in Birmingham, and sending them drawings of what he wanted for the glass; all of the glass, including the windscreen, is bespoke. If you did that today, you’d be told where to go.”

The powerplant chosen was an ‘E Series’ 2.2-litre straight six from an Austin Princess ‘Wedge’, complete with its Borg-Warner BW35 three-speed automatic gearbox, ordered brand-new, Matt recalls, in a crate from British Leyland.

It wasn’t silver originally. The Furia is thought to wear Aston silver paint because Don had a decent supply of it; as originally built, however, it was burgundy, before Don changed his mind. A specially-cast ‘F’ bonnet emblem sat, three-pointed star style, in the middle of the lid, allowing access to the front-mounted fuel tank when turned.

The heist that scuppered the project

Matt said that his father had no plans to produce the car in quantity – like the Quintana yacht, the Furia sports car was a one-off built on a whim, to his exact requirements, with the moulds produced to make spare panels if required. Suspension was adapted from other BL cars: at the rear, a Rover P6 de Dion unit was employed, its inboard discs converted to outboard drums. The rest of the running gear has yet to be identified.

Purists may baulk at the choice of an E Series engine, but it puts the Furia in a very special group of low-volume British and Commonwealth sports cars; spun through 180 degrees, the compact power pack had a seven-bearing crankshaft, stout reliability, and a massive parts network with which to call on. Certainly, the E Series was good enough for the likes of the Gilbern T11, unique Bohanna-Stables Diablo (the precursor to the AC 3000ME), and the Clancy Mirella/Mirabella 230TS, the car in which the Furia most closely resembles in finish, specification and layout.

Styling for the car was, in Matt’s words, “done on the back of a fag packet”, but Don knew what he liked and knew how to turn his drawings into polymer. Squat, wide and low, there are strong Frua and Fissore influences in its shape, not least the front end, which, with its front panel headlamp cut-outs, apes the Trevor Fiore-styled TVR Tina/Trident.

The front cowl is, instead, resolved with quad headlights in a manner not unlike that that of the Italdesign Asso di Picche, with traces of other contemporaries, including the GKN FFF 100, Aston Martin DBS, and two notable Frua cars – the BMW 2000Ti and Dodge Challenger Special – seen in its front three-quarter profile.

Unfortunately, while few remember the Furia in period, it wasn’t the last time someone took an interest in it. Perhaps not knowing what the moulds were for, its tooling and drawings disappeared during a break-in at SS Spars. Don’s family, including Matt, a small boy at the time, have speculated that the burglary could have been an inside job. The moulds and plans have never been seen since. “Dad had some conspiracy theories, particularly of how the later DeLorean resembled the Furia in some ways.”

Finished between 1975 and 1976, the Furia was completed at Don’s home in Hargrave, Northamptonshire, an eight-acre vineyard built, as you might have guessed, to his own specification. It included a joinery workshop and spray booth big enough to accommodate the car.

The Furia was shaken down at Brands Hatch to prove its worth. Don, a British Racing Drivers’ Club member, pulled some strings. “He was impressed at how well it performed,” Matt recalls.

Sadly, Don didn’t remain enamoured with the Furia for long: with just 34 miles on the clock, and infuriated by a fuel leak he couldn’t trace, the Furia was confined to a garage within the grounds of his home. Matt was tasked with cleaning and polishing it frequently; stuck in the garage it nevertheless “used to gleam”, Matt says.

By 1990, however, Don was considering redeveloping the Furia’s garage into a living space for a family member; photographed in the courtyard when it was unearthed, it was then pushed into a space outside the adjacent garage in which it was lovingly constructed.

The Furia would have otherwise been doomed to obscurity, had a member of the Pistonheads forum not interfered. It’s inaccurate to call the Furia a ‘barn find’ of sorts; stricken it may have been, but it was never meant to be in the public eye. The invited visitor saw the Furia and, unsure of its identity, took photos and shared them to a Pistonheads forum. The images baffled both the regulars and the Duegi Editrice forum in Italy, from where, it was inferred, the car originated, owing to the nameplates still clinging to its wings. An Italian restauranteur in Rushden had chosen the name: Don wanted an exotic moniker, and ‘Furia’, translated as ‘Fury’, fitted the bill. It would prove worryingly apt.

However benign his intentions might have been, Matt says the forum poster didn’t have permission to take those pictures on private property and share them. (We tried to get in touch, but our email to the forum poster went unanswered.) As debate over the Furia raged online, it attracted unwelcome attention. The Rawlings family were inundated with people turning up asking about the car, having worked out its location from the clues left in posts. Legal threats were issued, and the images were taken down.

Then, in 2020, aged 91, Don Rawlings passed away, leaving behind the Nymphs and Furia as his automotive legacy. His grieving family didn’t know what to do with the car, and owing to its fibreglass construction, no breaker’s yard would take it.

How the Furia was saved

Two years later, with the family home sold, Darren Collins, of Dowsetts Classic Cars, entered the story. His Herefordshire car manufacturer and restoration firm, best known for its Tipo 184 component car series, may never have known of the Furia – until a chance meeting put him in the picture.

“[Matt and I have] spoken over several years [he runs a firm near Dowsetts] but only recently did he let on about his Dad and the Furia when his Mum’s house was sold and it was in need of disposal! It was a massive surprise,” Collins tells us.

An agreement was made for Darren to restore the Furia and get it running again – with the intention, once completed, of donating it to a museum, alongside Don’s extensive trophy cabinet.

Upon seeing the car, Darren was stunned at the quality of its construction and began his own investigations into its origins. The resemblance to the TVR Trident was too much for Darren, who felt the Furia’s front end too close to the Trevor Fiore-designed car to be a coincidence.

Pushing the Furia around for our photos (made possible by Darren’s use of a set of Triumph TR7 wheels, its ‘F’ capped BRM Alcans, flat-spotted after their tyres disintegrated, remain safe) reiterates its low stance. The drivers’ door, recently persuaded open again by the Dowsetts team, revealed its clever use of the Ford and Smiths parts bin. A particular highlight is the dished three-spoke steering wheel, complete with Furia ‘F’ serif logo, shining proudly from the boss more than five decades after it was first cast. A fully-trimmed engine cover, acting as a rear luggage deck, separates the cockpit from the 2.2-litre E Series, which, when uncovered, reveals its rocker cover and twin SU carburettors.

Glancing at the nearside inner sill reveals the rivets attached to the stainless-steel chassis leg and front bulkhead, its finish still shining among the cobwebs and dirt in the cabin. That same attention to detail extends to the underbody, where a tidily executed twin exhaust system sits between ducts meant to direct air under the Furia’s tail. Buried under the spoiler are a pair of Dolomite taillights, but to call the Furia a bitsa would be to denigrate it.

Collins, well versed in the intricacies of car production, concluded that the Furia would be prohibitively expensive to make today: “I don’t know where to begin to price all the parts on the Furia as they’re exquisitely cast in aluminium, bronze and stainless steel (which is extremely costly).

“The best guess I could offer is comparison to something like our handmade Dowsetts Comet which starts at £150K and only contains our bespoke cast aluminium headlight bezels. [The Furia would cost] a figure of maybe in excess of twice that in today’s money.”

“I can’t think of anyone better to restore the car,” says Matt. His mother, Don’s wife, was in agreement when Darren visited. Separating the body from the chassis will be one thing; determining the many steps taken in the construction of its ‘tub’ will be another altogether.

Not that Darren doesn’t have the facilities or the know-how. He plans to document the restoration as he goes online – but is calling on fellow enthusiasts to help identify the parts used. Matt recently found the Mercedes-style Furia bonnet emblem at his late father’s home; stored away for many years, it will allow access to the front bonnet and fuel tank, allowing Darren to finally fix the leak that took the Furia off the road.

Darren is keen to learn more about the car and its rumoured Trident connections; after five decades stuck at 34 miles, the Furia’s odometer is set to roll once more.

Thanks to: Matt Edmonds; Darren Collins, Dowsetts Classic Cars; Dorothy Brawn, Irthlingborough Historical Society; Brian Stapleton – Historic Sporting Trials Association; Aston Martin Owners’ Club

Read more

Ran when parked: How do barn finds end up there in the first place?

This barn find packs tons of cool cars, but we have questions

Where have all the shabby Ferraris gone?

What a great story. I really hope they succeed and get this extraordinary car back on the road.

What a truly wonderful thing. I can’t wait to see her completed and running again. An incredible story of what sounds like an incredible man. Well done to all involved in bringing her back.

It has a very close resemblance to the Trident which Bill Last built in Ipswich.

I have a feeling that Winterbottom may have had a hand in the TVR Trident and the Trident Ventura , what a history if it can be pulled together.

What an amazing story, and an extraordinary achievement. So very pleased that this creation will be lovingly refurbished, and perhaps made available for enthusiasts to view. Brilliant.

A wonderful find, a unique piece of British motoring history.

As with so many individually designed sports cars, the design is superb from some angles but awkward from others.

The front end is very distinctive. The side view works from the front to the B pillar where everything goes a little awry. The rear quarters are awkwardly heavy and the window line doesn’t fit the waistline well. The rear view? Someone appears to have lost interest by then.

The disjointed whole reminds me of the Jaguar I-Pace, a car that looks as though it was designed by three or four different committees who didn’t start talking to each other until it was far too late.

Would be great to see this restored to former glory…. I see a bit of De Tomaso Mangusta in those lines.

The TVR Trident was of course designed by Sheffield-born Trevor Fiore, who also helped to productionise Bill Last’s Tridents which, whilst being based on the TVR Trident and looking broadly similar, were very different cars in terms of size and proportions, with no common parts at all apart from the V8 engines of Trident Clippers. Oliver Winterbottom played no part in the design of either the TVR Trident or the Trident Clipper/Venturer (NOT ‘Ventura!)

What a shame the talented creator could not have revealed more about his marvelous one off car when he was still alive. “Inundated” with visitors as a result of its discovery? I doubt it, maybe a handful at most. People really are very odd about privacy, I for one am very grateful it was “outed”, even though it could be seen from the public highway anyway! Legal threats? Good grief how out of proportion. And after all that the family really just wanted to scrap it after the builder’s death but “owing to its fibreglass construction no breaker’s yard would take it”. How reverential. So, by the skin of its teeth it survives, and I’m sure many people will be interested and enlightened by the story of its rebuild. Good luck to those involved.

I’m willing to bet my mortgage Trevor Fiore played no part in this car. Yes it may resemble exotic cars of a decade prior, but by the time of this cars construction in the mid 70s Mr Frost had moved on and up somewhat, his output of the likes of the Alpine A310 being a a league more developed and mature. What we are looking at is the product of an extremely gifted amateur.