I pressed down the clutch pedal again and pushed the gear-lever into first. This was it. My heart was thumping away so fiercely I could hear it in my throat. Ten yards away lay the the main road. It was as dark as doomsday. I released the clutch very slowly. At the same time, I pressed down just a fraction of an inch on the accelerator with my right toe, and stealthily, oh most wonderfully, the little car began to lean forward and steal into motion. I pressed a shade harder on the accelerator. We crept out of the filling-station on to the dark deserted road.

–Danny the Champion of the World

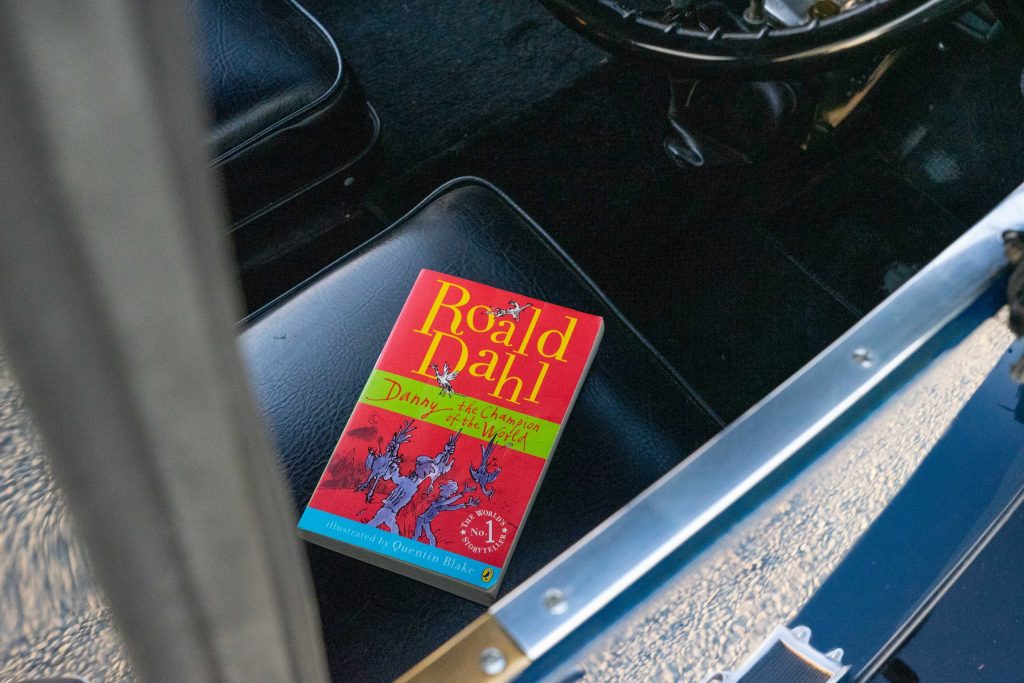

Of all the fantastical and marvelous stories told by children’s author Roald Dahl, none ever stuck in my head the way Danny the Champion of the World did. Narrated by the titular Danny, an intrepid 9-year-old, the story is filled with characters that illustrate the coming-of-age moment in a child’s life when you discover that adults are far from infallible. It’s a story of wonderment, capriciousness, and some arguably morally justifiable poaching. And it is a story about cars.

Dahl himself was something of a BMW enthusiast which, as we shall soon see, fits rather nicely into this story. But the cars of Danny are the typical cars of the English countryside of the mid-1970s. The villainous and supercilious Victor Hazell drives a huge Rolls-Royce, but Danny and his father worked on more ordinary fare at their little two-pump filling station and garage. But, together, they do fix one special car, which becomes an unlikely hero in the book. An Austin 7 – the “Baby Austin.”

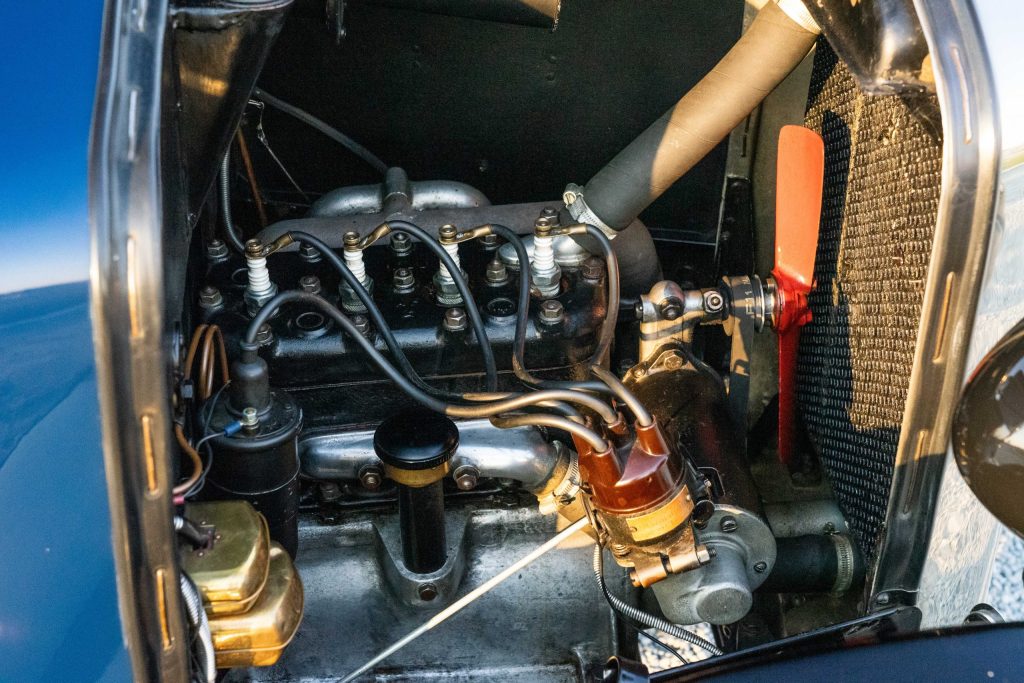

Produced from 1923 until 1939, the diminutive Austin 7 revolutionised the British automotive industry. The size of impact was inverse to the size of the car. It had a track just 40 inches wide and was scarcely 9 feet long. The engine displaced 747.5cc – any time you’re counting half-ccs, things are pretty tiny – and produced about 10 bhp. All in all, it was about half the size of a Ford Model T.

The example you see before you is a 1929 model, and it belongs to Dave and Christine Walker. The Walkers themselves are British imports, having moved to Canada from Gloucester in the late 1960s. They brought an enthusiasm for British motoring with them: Along with the Austin, their driveway accommodates a Jaguar F-Type and a Mini Traveller.

“Oh, I don’t like to trailer it,” Dave says, “I just drive it everywhere.”

Having owned an Austin 7 in his youth, he found this car in Bradford-on-Avon in 1997, thanks to a tip from the registrar of the Austin Seven Owners Club. An incomplete restoration, the car was crated up and shipped to Montreal, then via train across to the West Coast, where Dave finished the restoration himself. The crate it came in was in such good condition, he built a garden shed out of it. This is a very English thing to do.

Sitting side-by-side in the tiny Austin can best be described as “cheek-by-jowl.” The Walkers call their car Chummy, as you need to be on good terms with whomever you’re riding along with. And yet, there’s seating for four, and the controls for this near-century-old machine are quite conventional. The only quirk is the separation of rear brake (foot-pedal operated) and front brake (hand-operated lever).

To put this car further in context: The Austin 7 is arguably the ancestor of the original Mini. The small size is not the point – it’s the democratisation of mobility. When the first Sevens were made, most British cars were either large vehicles for the wealthy or toy-like cyclecars. The owner of an Austin Seven, original purchase price £150 sterling, could comfortably drive their family around the winding country roads of England’s green and pleasant land.

Thousands of them did, and the Austin Seven effectively killed off all the other microcars, just as the Mini killed off the post-war “bubble cars” decades later. Sevens were simple in construction, frugal in operation, and easy to keep on the road.

Working together, we released the valve springs and drew out the valves. We unscrewed the cylinder-head nuts and lifted off the head itself. Then we began scraping the carbon from the inside of the head and from the tops of the pistons.

The writing in Danny concerns itself mostly with the quirky characters and madcap methods of poaching pheasants. But the book carries a clear thread of the joy and delight in taking something mechanical apart and putting it back together again. Danny’s father, William, waxes ecstatic about the magic of it. “Just imagine being able to take a thousand pieces of metal . . . and if you fit them all together in a certain way . . . and then if you feed them a little oil and petrol . . . and if you press a little switch . . . suddenly those bits of metal will come to life.”

As a child, reading these words and dreaming of the ability to drive off on midnight rescue missions, how could you ever fail to fall in love with engines and cars? Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory held no greater wonders than the ability to understand the turning of pistons and the meshing of gears and the glorious, wondrous feeling of being behind the wheel.

The Austin Seven was the first such experience for many people, and as such, it left a huge legacy. A rebodied Seven called the Swallow set the stage for the founding of Jaguar. Bruce McLaren’s first racing car was based on an Austin Seven. The Seven was built under licence in many countries, including in Germany, where it was the first car BMW built, the Dixi. The design of the Seven was also somewhat controversially similar to the Datsun Type 11 of the early 1930s.

The Walkers’ Seven is an impeccable example of the breed, with a trophy cabinet to match. But it is no mere show car, still regularly out and about on the roads, trundling along cheerily and brightening everyone’s day. No pedestrian fails to smile as we pass. A couple of parents at a child’s birthday party hurry over with questions when we stop for pictures.

Because to see an Austin Seven out and about on the roads is to immediately recognise that motoring is a type of magic. We forget that magic, behind the wheel of some modern machine, late for work and less concerned about the experience than why the darn smartphone won’t connect properly. But the magic is still there, if you take the time to look, the way a child would.