While most will think of The Italian Job (1969), perhaps even The Bourne Identity (2002) as the archetypal Mini movie capers, there are endless others where Mini didn’t get quite such a speedy role, Get Carter (1971) for example, though my own choice is Shot In The Dark (1964) arguably the Mini’s film debut. With a short-lived role in the second (and the best) in the Blake Edwards Pink Panther series, the Mini is the getaway vehicle for Inspector Clouseau (Peter Sellers) and Maria (Elke Sommer). Naked as the day they were born, the two escape from a nudist colony. It’s a weird scene and a really weird Mini, with horrible white-wall tyres and basketwork sides, which really were made out of wicker, sanded down and varnished. And it’s all going swimmingly for the couple in their birthday suits, before they get stuck in a Paris traffic jam, passers-by move in to ogle and the screaming starts…

There aren’t many Mini stories left untold by now, though I still love the tall story that designer Alec Issigonis designed the original Mini’s cavernous door bins to carry the ingredients of his favourite drink, a gin martini: a bottle of Vermouth and Gordon’s gin, with a lemon and a carton of olives squeezed into the side… He was certainly obsessed with the size and weight of doors, reacting against the enormous examples on American cars, which he said were so large you could build an entire car out of them.

The mercurial design engineer had been hired back from Alvis by BMC Chairman Leonard Lord late in 1955 to work his wizardry on a small urban car. Lord’s reaction to the swarms of German bubble cars on UK roads echoed that of Herbert Austin’s hatred of the proliferation of motorcycles and sidecars before World War Two.

“‘God damn these bloody awful bubble cars,” he said to Issigonis, in March 1957. “We must drive them off the streets by designing a proper small car.”

Things were so much simpler then, but the development team comprising Issigonis, his old colleague Jack Daniels, Chris Kingham from Alvis, four draftsmen and a pair of student engineers seems stripped to the bone even in those straitened times.

Needs surely must, however, since was Britain still wracked by Suez Crisis. In 1956, against international sentiment including that of America, Britain, France and Israel took military action against Egypt to prevent the nationalisation of the Suez Canal. Their attempts failed and the effects on Britain were profound, signalling its diminishing international influence, cutting off a fifth of its oil supplies, causing a run on the pound, fuel rationing and the resignation of prime minister Anthony Eden.

Suddenly, small, lightweight, economical and cheap cars were the new black and Issigonis’s team, which had been looking at a replacement for the Minor, were now thinking even smaller, lighter and cheaper, which played right into its strengths.

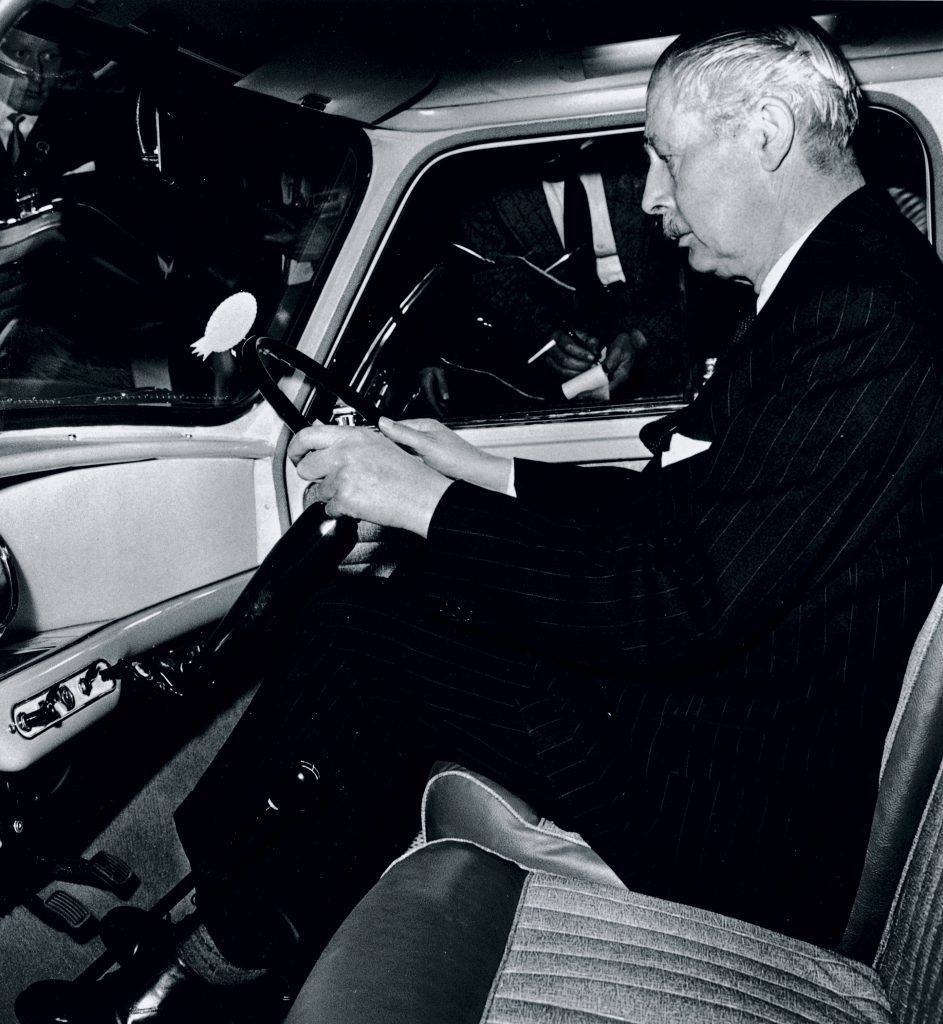

I had always thought that the prototype-to-on-sale date was just a year, aided by my well-worn copy of Laurence Pomeroy’s The Mini Story. This would make the Mini one of the fastest-ever cars to market (along with the first-ever 1948 Land Rover). Over to the ever reliable Keith Adams and Ian Nicholls of ARonline who claim to blow that one wide open revealing that a Mini prototype (they were known as ‘orange boxes’) was actually driven by Lord and his deputy George Harrison in July 1957, which is a whole year earlier than I had been led to believe, though it was still pretty fast to market for a car that debuted so many innovations and not just its diminutive size.

By all accounts, after about five minutes behind the wheel, Lord turned to Issigonis saying: “Alex, this is it, I want it in production.” Issigonis bridled saying what about the cost and Lord is reported to have replied: “Don’t you worry about that; I shall sign the cheques; you get on with getting the thing to work.” Within two years, Mini was on sale.

Photos: Daily Herald Archive/National Science & Media Museum/SSPL, and Evening Standard/Hulton Archive, both via Getty Images

Those 10-inch wheels meant Dunlop had to make a special tyre for the Mini. The rubber suspension of the early cars was designed by Alex Moulton, though I did once drive his own interlinked ‘wet’ Mini, which not only handled but also rode like a dream. Then there was the car’s width, which meant there was no room for a transverse engine alongside a gearbox and instead the engine was placed on top of the transmission with a set of transfer gears and sharing the same lubrication. Not the most efficacious practice I will attest and my own Mini Cooper with a Rushen Green racing engine had a big magnetic sump plug which I would anxiously examine at every oil change for evidence of broken teeth or other expensive bits.

Mini represented great British development and derring-do to rival that of the jet engine, the bouncing bomb or radar (for RAdio Detection And Ranging), yet somehow the Mini is never quite credited with the success it achieved; somehow it has become subsumed in a back story of Leyland’s inefficient working practices, hopeless management, bolshy unions, engineers in woolly tank tops and just not being very good. Yet the conception and design process were as modern as the hour. Nissan is wont to boast about how it has an entire department of engineers trying to fit a variety of common objects in the company’s prototype interior models, with a testing rota of every sort and size of company personnel, yet that’s exactly what Issigonis and his team were doing back in 1957. Former Aston and Jaguar designer Ian Callum used to describe how his team would sweat every millimetre of metal and gram of weight, yet as Mini design engineer John Sheppard described: “He [Issigonis] knew what he wanted and he made sure he got it. He’d come round holding an ounce weight and say: ‘Have you saved that for me today?’ Weight was very critical.”

Issigonis could be a martinet and wouldn’t listen to criticism or allow design changes to solve inherent problems which cost BMC millions in warranty and rectification. The first Mini’s wrongly overlapping floor pans were a classic example allowing road spray into the cabin, yet despite his wet socks, Issigonis refused to countenance a fix. Yet there was nothing jokey about the Mini or its design team; these were serious and super-talented people at the top of their game. In 1959 at the launch of ADO15, The Guardian newspaper reported: ‘The British Motor Corporation to-day announces two new small cars which provide striking evidence of the new thinking that has gone on within the industry. In its Morris Mini-Minor and its Austin Seven, the corporation is offering vehicles that can carry four passengers with speed and economy and can fairly claim to be called family cars’.

‘Wizardry on Wheels’, then, and cheap, too, with both models costing £496 19s 2d including purchase tax, and £537 6s and 8d for the deluxe model, with a fitted heater and bumper overriders.

Too cheap? Possibly at first, especially as the early sales were slow, which reduced the opportunity for all important economies of scale. But there’s a lot of misinformation about this, especially that old trope about Ford stripping down a very early example (in fact it was two) and concluding that BMC was losing £30 or six per cent of the purchase price on each Mini it sold. This Ford hated the Mini and its success, thinking the cheap family car market was theirs. When I first started in this business long ago, one ageing Ford exec confessed that the company had been livid when The Queen took a well-publicised drive in a Mini with Issigonis.

In 1959 when the Mini and Triumph Herald were launched, Ford’s rival was the two-door Anglia 105E, which saw Elwood Engel’s tailfins and reverse-sloping rear screen design sitting on a quite ordinary rear-drive chassis, but it cost £610 5s, over £100 more than the Mini. Ford’s main rival was that year’s £494 2s Popular, a stupefyingly vin ordinaire saloon with a stripped out interior sans quarter lights, and parcel shelving and a 1.1-litre side valve engine and three forward gears – yum!

In fact, even Ford’s 1962 Cortina wasn’t as advanced as the Mini and the blue oval didn’t offer a proper transverse-engined, front-drive small car, the Fiesta, until 1976, a car with such marginal profitability that Ford is now quitting that market segment entirely.

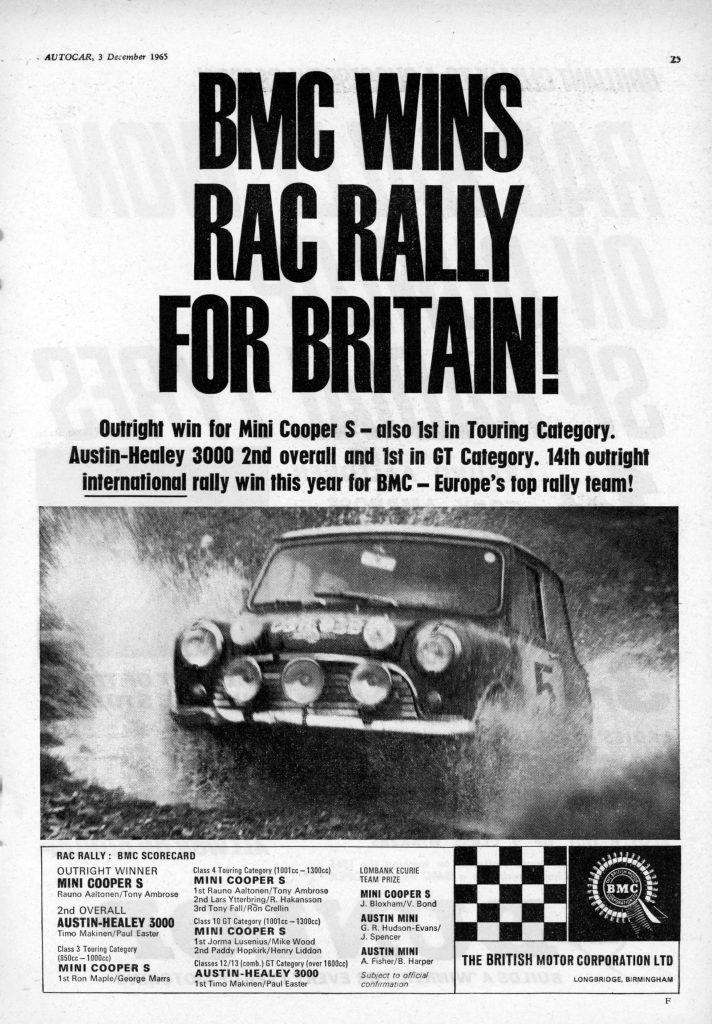

What Sir Terence Beckett and his cohorts completely ignored was the fact that BMC understood something which it took Ford’s three-shaves-a-day bean counters decades to understand. And that is the way you attract buyers with a low-priced starter model, but immediately price everyone up in the showroom. Recall here, that while early Minis were cheap, BMC quickly diversified into myriad higher-margin models such as the Super, Cooper and Cooper S, Traveller, Countryman, Commercial pickup and van, Moke, Elf and the Hornet, not to mention the split of Austin and Morris-badged examples. Ford’s analysis was conducted in the early days of the Mini when production was ramping up – eventually it would be produced at Longbridge and Cowley as well as in Australia, Spain, Belgium, Italy, Chile, Malta, Portugal, South Africa, Uruguay, Venezuela, and Yugoslavia. There was also the BMC 1100 model (code named ADO16), which was heavily based on the Mini and increased component economies of scale.

By 1962 three years after launch, UK sales had risen from the first year’s 7,800 to 116,000 and with Britain by then two years into membership of the European Free Trade Association, the tariff-reduced Mini had overseas sales which had risen from 11,949 to 100,087. Prices too, had risen from £496.19 to £526.25, according to Rob Goulding in his book, Mini. And as Brian Laban wrote in his book, The Little Book Of Mini, BMC was clear that the way it attributed the overheads, meant that Mini always had made money.

What’s more there’s a thorny issue of overseas production and sales, which has confounded various distinguished Mini Boswells over the years. How many were built? I’ve seen several estimates, all around the 5.3 million mark, but in a forensic piece of work, AROnline’s Nicholls estimates a total of 5,828,171 and 6,060,558 if you include Innocenti Minis, and while UK sales were declining, overseas sales were increasing at a rate to compensate. As he astutely puts it: ‘The whole saga that enabled Leyland to gain the upper hand in the merger negotiations with British Motor Holdings, was based on an analysis of BMC’s domestic performance in comparison with Ford UK. This revealed the insular mindset permeating the City of London and the financial institutions.’

Too true.

Rover held onto the Mini for too long of course, there’s an old joke that by the time of its final bow in 2000, the Mini was 30 per cent larger than the first example because the press tooling was so worn out. The thorny issue of a Mini replacement became stuck in the maw of British Leyland politics and a distinct lack of investment funds. Even later on, the Rover Group didn’t have the funds to build the Mini Metro’s innovative replacements, the 1997 Spiritual and Spiritual Two concepts. Yet in the end, when BMW came to design a new Mini, it tipped its cap to the past, by choosing Dave Saddington’s retro design.

I was there in 1997 on the eve of the Frankfurt Show at a hastily convened BMW press conference in an industrial warehouse. At the end of the perfunctory speeches, the ACV30 concept burst through a paper-walled crate onto the stage; white roof, white door mirrors and white wheels, fire-engine red coachwork; it sounds like an Ian Dury number, but it looked good then and still does today.

They’d been working on it for three years and to the sheer infuriation of Rover insiders, BMW gave all the credit to their own Frank Stephenson. Down in the reserved front seats, grey-suited Munich execs hand jived to Iggy Pop’s Lust For Life, a song about heroin dependency. Regardless, the new Mini went on to become a great success.

Part of my childhood, driving Minis, fixing Minis, welding Minis, tuning Minis and drying out the distributors of flooded-out Minis was life. My favourite story? Nicky Coates and I were great childhood friends. We did everything together, fuelled with Alphabetti spaghetti on toasted slabs of buttered white bread, washed down with Nesquik and followed by Angel Delight. His mum had a Mini Traveller; you know the ‘Woodie’, with the timber rear frame. Living next to the sea, however, warped the spars and the rear doors had a habit of springing open when you least expected it. On the way home from school, Nicky and I would sit across the rear on a bit of old carpet, with the family Labrador between us. One day Mrs Coates took off at the traffic lights outside the police station with a bit too much vim and by the time she was 100 yards up the road, Nicky, me and the dog were sitting in the road right outside Lymington police station – all of us as embarrassed and bemused as Inspector Clouseau and Maria all those years ago…

Read more

The Full English: Ford Escort

The Full English: Morris Minor

Icon vs Underdog: Mini vs Morris Minor

Excellent review of the mini.

I missed out on a one family owned from new Mini in Snowberry White (?) a few years ago when it came to live in Ormskirk rather then London where it had been stolen/recovered several times. I was offered it for £3000 by its pensioner owner – doh! Not seen it recently but it was living in nearby Burscough.

Thank you both. And Mr Blaxall, find that Mini now!

All the best,

Andrew

I took on my mother’s 1959 Austin Seven deluxe. It was an amazing little car on which I learnt basic mechanics before moving on to a 997 Morris Cooper (a rust bucket), a mini 1000, and with the arrival of our first child, a 1071 cc Clubman Estate.

The Austin Seven took me to the South of France and back without missing a beat. A brilliant concept that’s lasted.

My brother could change a Mini clutch in 25 minutes. This was necessary because his Mini van was running a 1,293cc Cooper S engine through a standard Mini transmission.

Still got my ’68 Cooper S – it’s not going anywhere. Apart from another Rally Tour in a fortnight… it sits next to a ’68 big-block Mustang, and it’s always a toss-up which to take out.

Liking the sound of that two-car garage, Roger…

Minis in films.

The film about Clive of India and the Kyber pass was filmed in Snodonia in 1968 and in one of the shots you can see my red and white S in the distance. It was a 1963 1071cc model and we took it to the mountains for some fun driving on white roads.

I still run the family 1967 Austin Seven mini which my Mother had new

on January 1st 1968 and drove

until she was over eighty. It is still in occasional use and was driven

on a Welsh coast run and to Gaydon for the Mini 50th Birthday

celebrations in recent years.

My 1965 Morris Mini Cooper shares a garage with a 1960 Porsche 356 Cabriolet. An interesting and diverse pair, both special for very different reasons. A great article, and excellent read, thank you.

Top of their game? 9X was even better, eg styling, engine and packaging. Snowberry white – had a Hornet in that colour and the paint was very poor.