A sensation of being almost out of control comes as standard equipment in an Austin Seven, Britain’s first ‘people’s car’, which was once described to me as a profound demonstration of democracy in action; the driver being a minority vote in the direction and speed of travel…

“You need to use the kerb to slow down,” said my Austin 7 co driver in the Vintage Sports Car Club’s infamous Measham Rally as we careered down the hill into a Hereford Valley. This meant rubbing the wheels up against the granite sets that bordered the road in the hope that the friction generated would reduce the velocity at which we would surely meet our ends.

This was an Ulster replica so named because of the little car’s sterling performance in the 1929 RAC Tourist Trophy run on the Ards circuit in County Down, with a third place finish for Archie Frazer-Nash and a fourth place for S V Holbrook.

This 3.01-metre-long, aluminium-bodied, two-seater was far from an optimum entry into the VSCC’s notoriously tricky overnight navigation rally, which that year was held during a nasty January cold snap. Nor was its open top the best of weather protection and I seem to recall the Ordnance Survey map was papier-mâché within the first ten miles. You couldn’t see much to the front, either, as Richard’s idea of tuning up the Lucas ‘Prince-of-Darkness’ lighting on the little beast was to take one headlamp bulb out so that the other would glow a bit brighter.

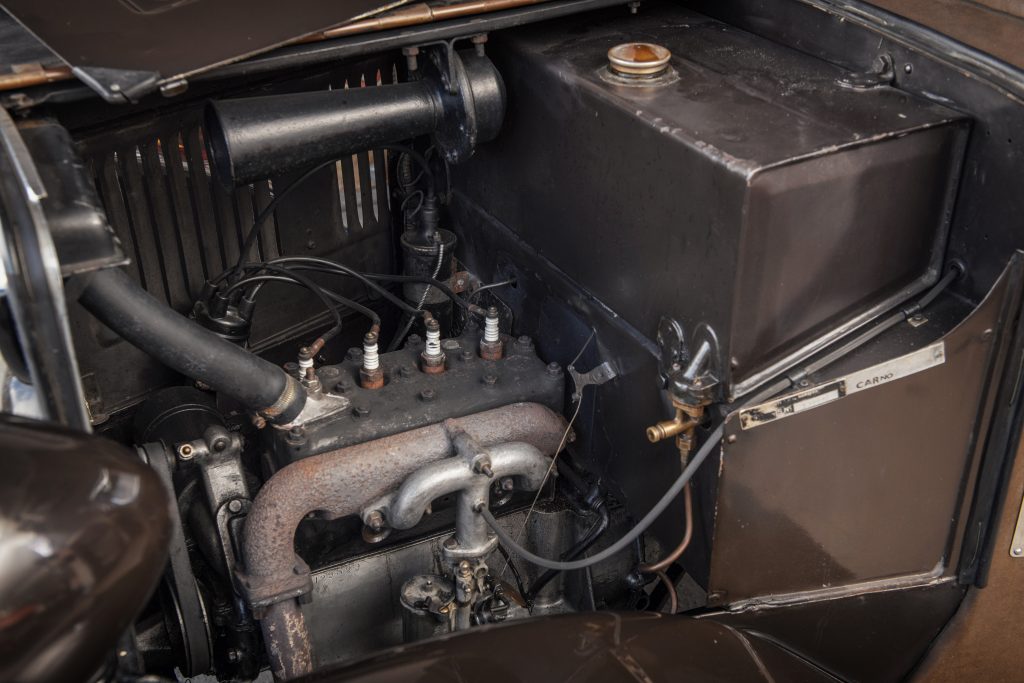

It was quite fast though, mainly as a result of its 430kg kerb weight which meant that Richard and I were the largest contributors to sprung weight. The engine had been tuned up, I seem to recall, with Renault 4 pistons, connecting rods and shell bearings on a pressurised Phoenix crank with a modified Volkswagen Beetle distributor. When I say fast, well, that’s a slight misnomer, think a top speed of about 60mph and 0-50mph despatched in a whisker under half a minute.

History perhaps, had best remain unblessed with my Anglo-Saxon response to Richard’s braking advice, but we must have slowed sufficiently to negotiate the subsequent icy ford at the bottom of the hill, the splashes instantly becoming ice on my Barbour jacket.

So let me tell you about these little cars, which by turns are the quintessence of automobilism, the most profoundly joyous devices, and at the same time, the very devil’s transport…

Billed as ‘a motor for the millions’, the Austin Seven was launched in 1922 in Claridge’s Hotel, so no irony there, then. It was championed and partly engineered by Sir Herbert Austin, whose eponymous company had been in receivership in 1921 and was facing one of the most disastrous economic downturns of all time. Facing huge opposition to his ideas from the board and the receivers, Austin decided to develop his little car on his own with his own money. He purloined the services of talented young draftsman, Stanley Edge to do the design work on the Austin Seven, according to legend on the billiard table at Austin’s home, Lickey Grange, although Edge later admitted that he did the donkey work of the design in an alcove off the billiard room.

Edge had worked in the aircraft design shop from the date of his 14th birthday in August 1917, but when the First World War ended in 1918, he managed to wangle himself a place in the car design offices where he had been noticed by Herbert Austin, who had asked him to bring his drawing board and come and live at Lickey Grange to work on the Austin Seven design, which at that point only existed as a huge sketch on the billiard table.

Austin had started his career at Wolseley in Australia, but had formed his own car maker in Longbridge in 1905. He much admired French cars and Edge recalled looking at power units from a number of French cars as inspiration for the new Seven, although he dismissed ideas that he’d been heavily influenced by the Peugeot Quadrilette as “…absolute damn nonsense.

“The eventual power unit was entirely my own,” he was quoted in Men and Motors of The Austin by Barney Sharratt. “But I’ll tell you what did influence me. I had a sectional drawing of an FN four-cylinder air-cooled motorcycle of 750cc, that used 52mm bores.”

Using rule-of-thumb proportioning, he sized down the engine into the four-cylinder 696cc engine from which the name Seven is derived from the RAC horsepower rating. Edge, who got no thanks for his hard work (although he did get a pay rise to £3 a week), had the foresight to leave a bit of meat on the cylinder walls, and after some persuasion, Austin allowed the first production engines to be bored out to 747cc.

Edge had never designed a car before and was continually sizing things up from existing drawings, such as the rear axle, whereupon Austin would put him right and specify a lighter smaller design. It was hand-to-mouth, against-all-odds development and Edge who would have his lunch and dinner delivered in the library on a tray and was sleeping at the Lodge, recalled an increasingly irascible Austin fighting his corner in the spring of 1922 to get test cars built. Development and Edge were moved into the Austin works and as Edge recalled: “I had produced drawings with proper tolerances on them so they didn’t have to change a thing.”

In secret, a small team including Alf Depper from the experimental department produced the first three Austin Seven prototypes, complete with a crankshaft made out of incredibly hard Kayser Ellision 805 key steel, which deprived Austin production process of Woodruff keys for a couple of weeks.

Priced at £165 at the launch, the advertising said that you could travel in comfort “at no more than the cost of a tram ticket”. Yet early sales were slow and it almost seemed as if the baby Austin was ahead of its time and the public didn’t initially take to the Seven, which its makers thought of as a proper car but made in miniature. Gradually, however, they started to understand that they could, like Mr Toad, enjoy the freedom and independence of the open road with their friends and families – Poop, poop!

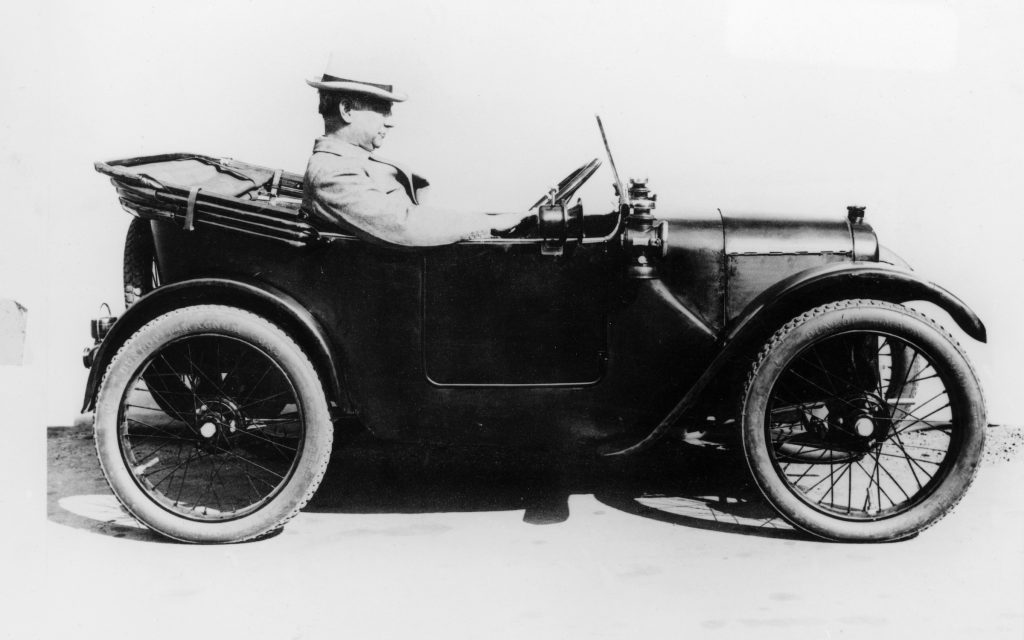

The early cars were open-bodied four seaters, just 2794mm long, with a 10.5bhp side-valve engine and a three-speed crash gearbox driving the rear wheels. But these were proper cars, with a conventional pedal layout and a little dashboard containing a speedometer, a clock, ammeter and an oil pressure gauge. The standard horn was almost larger than the cylinder head, but the whole car weighed just 381kg, with a worm-and-sector steering system and tiny cable-actuated drum brakes on all four wheels. Top speed was just over 50mph and performance was such that even small hills would slow progress to walking pace. You needed to get very good with double-declutching your way down the gearbox …

Yet they were fantastically popular, with about 290,000 built of which around 7000 survive today. It was built as a saloon, coupé, cabriolet, sports car, single-seat racer or commercial, with bodies made of wood, fabric, steel or aluminium. There were myriad types of Seven not including the unfairly maligned Ruby or the Seven’s replacement, the Big Seven. They were produced under licence in America by American Austin from 1930, in Germany by Dixi (which became BMW) from 1927 and by Rosengart in France from 1928. Nissan produced a version of the Austin Seven and Herbert Austin and Stanley Edge’s masterpiece was exported as a rolling chassis to Australia for local bodies to be fitted.

It provided the basis for the early race cars from Colin Chapman, a young Bruce McLaren and Gordon England as well as the basis for the rebodied Austin Seven Swallow, which was William Lyons’s alma mater before he founded Jaguar. Their robust mechanical layout also made them suitable for the most intrepid adventures, including round the world journeys, rallies including Le Jog and Peking to Paris. Most intrepid of all of course was that of Mrs Algernon Stitch, heroine of Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop, who drove her Seven down the stairs of the gentlemen’s public lavatory in Sloane Street.

My friend Richard’s model was perhaps a high point, but I’ve also piloted the lowly box saloons and a less-than-stellar coupé. A good one will wander around, following every joint and undulation in the road. It will demand levels of forward vision and anticipation worthy of the Delphic Sybil and mechanical sympathy of the highest order.

You’ll need a certain familiarity with the spanners, and patience but these are the simplest machines to maintain. A decent saloon with patina but quite useable will cost from about £5000, but prices go up pretty sharply for sports or cabrio models and it’s the sky’s the limit for one of the genuine Ulsters, even the replicas are pricey.

But while an Austin Seven is not for the faintest of hearts, driving any of these little cars is a delight, they’re the perfect pub car and ideal for touring the byways of merrie England, enjoying a world not just older and slower, but also more welcoming than the cut and thrust of our modern motorways and highways.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage for daily news, features, interviews and buying guides, or better still, bookmark it.

Good story, I am on my second 7″ restoration.

You can improve the brakes!

Dear Graham, thanks for the post. Blimey I wish Richard had improved his brakes! All the best Andrew

The brakes are not the best accepted. But when you take into account the excessive speeds that these cars do not achieve they are adequate. Herbert Austin when challenged on the subject said “ why worry about brakes , you have an adequate gearbox” . I’ve had 8 including two French built versions built under licence. During the 95th Anniversary run we visited seven countries. Buy yourself one and enjoy driving.

I learnt to drive in one of these it was a 1933, and is still on the road. Travelled to Switzerland in it and Italy.k

Oh Joanne, I’m in the Italian Alos at the mo driving a car I’m not allowed to tell you about and wondering how I can afford to bring my wife out here in my little Triumph. What a wonderful thought of you out here with an Austin Seven. All the best Andrew