While the auction world has fallen in love with the upper end of the Ford Escort ranges; the AVO cars, the twin cams and the RS models, my first memories are of an altogether different cadre of motorcar. My mate’s Mark 1 1300 GT; all vinyl seats and primer-grey wings. This was our two-door ticket to the Seventies rhythm and blues world of Canvey Island where Eddie and The Hot Rods and Dr Feelgood gigged.

With a stroppy teenager’s conceit, this felt like an important time and the Escort was just the ride to let us in, with its cramped rear seats and an exhaust that sounded like the snarl of Feelgood’s frontman Lee Brilleaux. We’d park it outside the Labworth for coffee or the Monico or the Lobster Smack pubs for pints, then onto see the band. At the time it felt like the fastest thing on wheels and despite Autocar magazine’s testers failing to break the magic ton by 4mph, I could swear we hit 100mph in that car on the way back to Southend on the Arterial Road.

By that time, that first Escort was getting on for a decade old, in 1975 the Mark II Escort had been introduced alongside the Mark I. Both versions sold together for at least a year, and both could distinctly trace their lineage through to the 1959 Anglia 105E. In fact, there had been an Escort-badged version of the dumpy looking 105E Squire estate.

These were the Ford years: Cortina; Transit; Zephyr; and Zodiac, vehicles which saw Ford encamped far from the forefront of technological advancement, but close to the summits of marketing brilliance and meticulous costing. Legend has it that Terence Beckett, Ford chairman, ordered a newly launched Mini to be reverse engineered, with the conclusion that BMC was losing £30 on each car sold. Back then, and even today as we wave goodbye to the Ford Mondeo, Fiesta, and Escort’s replacement the Focus, the blue oval has always been ruthless in its pursuit of profit.

Ford of Europe had been created in 1967, but preparations for a pan-European basis of the following year’s Escort model had been laid long before. Ford’s Halewood facility, which became the production home of the first Escort, had been purchased in 1959 and cross-European parts sources established. During its eight-year production life, the Mark 1 Escort was produced in Dagenham, Halewood in Merseyside, Saarlouis in Germany, Cork in Ireland, Nazareth in Israel, Homebush in Australia, Seaview in New Zealand, Taipei in Taiwan and Genk in Belgium.

What’s just as significant, is that Escort marked a sea change for European Fords, with inspiration taken from the hands of designers and engineers and into those of the product planners and marketers. Which perhaps explains why the Escort did not follow the front drive configuration of the Mini or the German Ford Taunus, or the rear-engine, rear-wheel drive layout used by various Fiats, Renaults and Hillman’s Imp, but stuck with tried and tested, cheap-to-build but resolutely backward looking front-engine and rear-wheel drive with a leaf-sprung live rear axle. It seems hard to believe that Ford was still conducting feasibility and costing analysis into rack-and-pinion steering for the first Escort when it was already established practise for the Mini and various sharp handing sports models. The initial engineering bill for the first Escort came to just under £2 million by the time it was launched, though an extra £500,000 was allocated for lifetime engineering.

Yet in some ways it was that innate, penny-pinching conservatism which was the Escort’s saving grace. The engines were all bomb-proof derivatives of the 105E’s Kent engine and the single-rail, four-speed gearbox was a byword for shift quality. The Escort name was used mainly because the Germans didn’t like Anglia as a name. There are lots of theories about this including writer Jeremy Walton, who in his book, Escort. The Development and Competition History, says that one Dunton engineer told him that the Germans didn’t like Anglia as a name because it reminded them of the World War II East Anglian bomber bases…

No matter, the Escort went down a storm and in June 1974, six years after it had been introduced into the UK, Ford announced that the two millionth Escort had been built, which was a total production number previously only been seen in North America.

How did that happen? Well marketed and well made the Escort certainly was, but its specification was antediluvian compared to some of the alternatives. No small part of the Escort’s ‘it’ factor must be laid at the door of Walter Hayes, the former newspaper man who had been taken on as director of public affairs by Sir Patrick Hennessy, Ford UK chairman. With Ford of Detroit in its Total Performance period, Hayes was fully persuaded of the ‘win on Sunday, sell on Monday’ ethos. At the time Ford of Europe’s glamour quotient was off the bottom of the scale, but Hayes was undeterred, first doing his famous deal with Colin Chapman of Lotus which resulted in the Lotus Cortina, then persuading the company to enter Formula One with the famous Ford Cosworth DFV engine, and after that persuading the blue oval to go rallying with its unprepossessing small family saloon, the Escort.

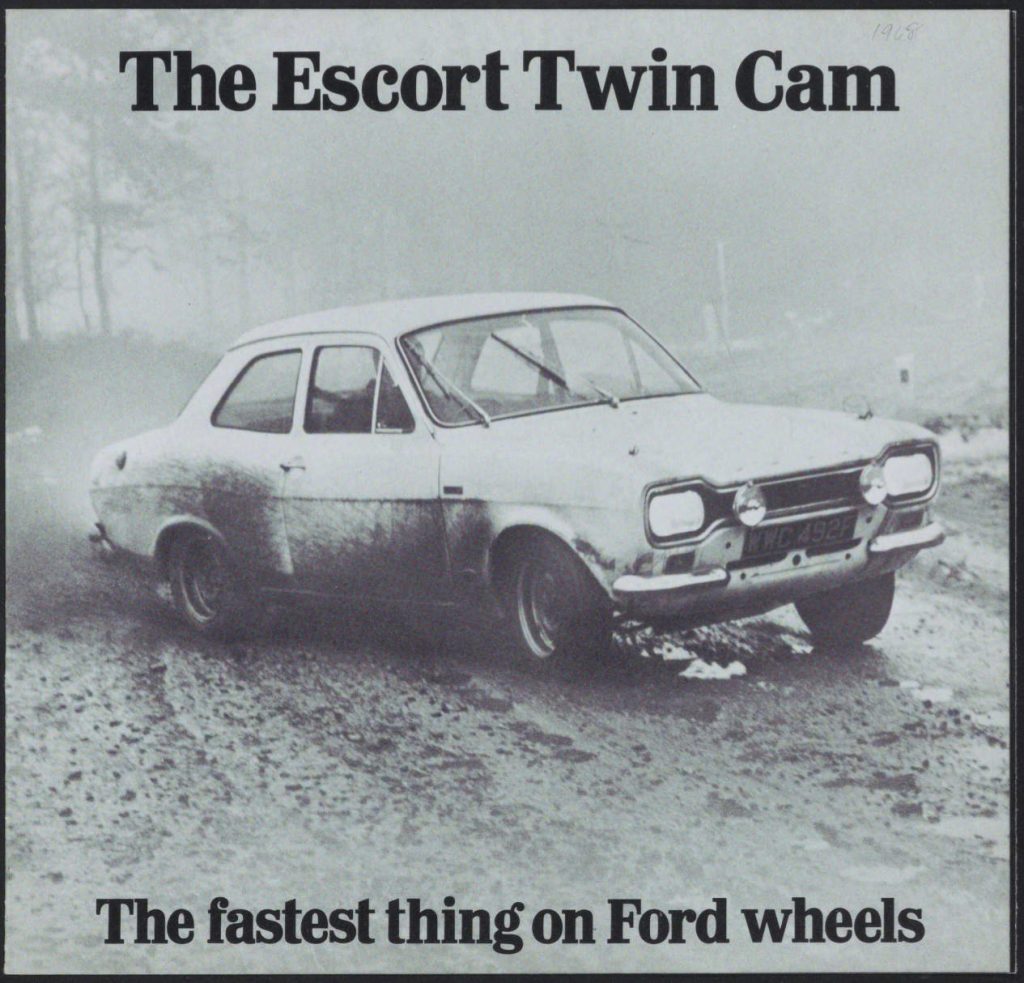

Those sporting Escorts are stuff of legend. The Twin Cam model with its Lotus Elan engine and the RS1600 with its Cosworth BDA were all-conquering on road or stage. Rallying changed forever with the Escort, just as it did in 1980 when Audi launched the original Quattro. The Escort launched the careers of the Flying Finns such as Hannu Mikkola, Timo Mäkinen and Björn Waldegård as well as Roger Clark (winner of the 1972 RAC Rally). And let’s not forget how it propelled motor sport moguls including David Richards of Prodrive and Malcolm Wilson of M-Sport which began at Ford’s Boreham rally HQ.

On the race track, Alan Mann Racing fitted 200bhp Formula 2 engines into his Escorts for drivers such as Sir John Whitmore, Frank Gardner and Jackie Oliver, and David Brodie fitted out his Mark I ‘Run Baby Run’ with a stretched 2.1-litre BDA and won an estimated 200 races between 1969 and 1972, some of which I witnessed from the spectator bank on the outside of Brands Hatch’s Paddock Hill bend.

My Escort rally experience came in an entirely accidental way as I spannered my way through college and ended up as an unpaid crew member for a Mark II Cosworth-engined Escort on the UK rally championship, including the Circuit of Ireland and the Manx. Before each morning’s start we gently warmed this exotic, raucous machine by driving up the road and I still retain the ability to while away an entire afternoon listening to hepped-up Escorts and watching the jaw-dropping virtuosity of the likes of Ari Vatanen, Bertie Fisher, Simon McKinley or Frank Kelly as they dance the back end around as if entrants on Strictly Come Dancing – On Michelins.

So abiding is this love affair, that most years (usually before I have had to pay my tax bill), I plan a visit to Den Motorsport in Maghera, Northern Ireland to hand over the readies for one of their Group 4 Millington-engined Mark II Escorts, which in the right hands will make your Porsche 911 look and sound like a toddler’s toy. The dream goes pop when HMRC tells me how much I owe.

Yet if those were the highs, then the beginning of the end of Escort’s motor sport glamour years came in 1980 and the launch of the Mark III Escort code named ‘Erika’, and Ford of Europe’s second-ever vehicle to drive from the front wheels. Rallying success with this generation Escort looked so much of a pipe dream that in 1982 Stuart Turner, Ford’s competition manager, commissioned the 1700T, a turbocharged Cosworth-engined homologation special driving the rear wheels, but the car was dropped in favour of the RS200 when the strength of the Audi Quattro threat became clear.

But if the Escort’s frisson had gone, Ford tried to get it back with the hepped-up XR3 version as an answer to Volkswagen’s successful Golf GTI. XR3 totted up over 10 per cent of UK sales (so did Golf GTI), but I’ve mixed feelings about that car, which was initially launched with a weedy tuning job on the 1.6 CVH engine giving just 95bhp, with a four-speed gearbox and a ride like a dropped cutlery drawer. I did several there-and-back in a day journeys to Manchester in one and my spine can remember every single bump on the motorway.

It took five speeds, fuel injection, and Rod Mansfield’s team at Special Vehicle Engineering to turn it into a credible Golf GTI rival, the XR3i. Now that was a half-decent car, though judging by the prices that the small ads are asking for an example today you’d have thought they were the best thing since fish grew legs.

What did give Mark III an almost priceless appeal was the endorsement of one Diana Spencer, Princess of Wales. Lady Di preferred to drive her own cars and there were a number of Escorts in that stable including a 1981 Ghia model, a cabriolet and that black RS Turbo model which sold for a scarcely believable £724,500 (including buyer’s premium) at auction last August.

Erika-86, or the Mark IV, was launched in 1986. This was essentially a face lift on the Mark III. There was an optional Lucas/Girling mechanical anti-lock brake system on the front wheels which could cadence brake just slightly faster than you could manage in a set of oversize wellies. It also introduced the heated windscreen which has since been a boon to all Ford owners on frosty mornings. It wasn’t a great car, but Ford had spent a bit of money on a new engine/gearbox subframe, although sometime during the production run it introduced the Tibbe key, which had a habit of shearing off in the lock and leaving you very stranded.

By 1990 that Escort IV had become a phenomenon, it was the world’s best-selling passenger car and occupying one in eight new-car sales in the UK. But it was getting long in the tooth and facing stiff competition from Vauxhall’s Astra, VW’s Golf, Renault’s R19, Rover’s R8, and Peugeot’s 309 amongst others.

Mark V code named CE14 was Ford’s answer and though they boasted they’d spent one billion pounds on development, it only just moved the game on despite its new bodyshell with a slightly longer wheelbase and torsion-bar suspension to give a bigger boot. The gasping CVH engines from the Mark III were still there and the five-speed gearbox was floppy and needed to worked hard to give any sort of performance which meant fuel economy fell as a result. The soft ride quality fell apart at high speeds, the handling was soggy and some cars (the 1.4 litre) didn’t even have anti-roll bars, to save money. The manual steering was low geared so you had to twirl the wheel like a raffle ticket dispenser to park or manoeuvre round town.

This was a terrible car. I was on the launch and said so, along with Autocar, Car and Top Gear. Ford found itself on the defensive despite its all-powerful marketing department and gazillion dealers; one market strategist even said that the Escort V was deliberately middle of the road, because it sold to middle of the road people, which might have been true but no one likes being called middle of the road.

A major facelift and overall came within two years of the launch, but that and the 1991 launch of the RS2000 and the 1992 introduction of the Zeta range of engines did little to dispel the notion that Escort V was a cynical car. As Abraham Lincoln said: “you can fool all the people some of the time and some of the people all the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time.”

Even the mighty RS Cosworth of 1992 didn’t do much for the Mark V, partly because it wasn’t even an Escort, but a down-sized rebodied Sierra Cosworth. It was effective if unlucky on international rally stages, winning just 10 events between 1993 and 1998. I was invited to its unveiling at a ritzy supper at Blenheim Palace and can vividly recall the excitement as the first Cossie was pulled off a covered trailer and fired up. Never mind the dull old road-going Escort, which we were there to celebrate, all we wrote about was the RS Cosworth…

The writing was on the wall for the poor old Escort, and while there was a Halewood produced Mark VI which was sold alongside the Focus, and even a GTi version introduced in 1997 (the only Escort ever to be so badged), the last Escort car came down the line in 2000. The plant was mostly transferred to Jaguar for production of the X-Type and staff training (excruciatingly called Green-Blood Training) was conducted on the old line producing the Escort van up to 2003 – those vehicles were reputed to be the best-ever built Escorts.

While former Ford Motor Company boss Alan Mulally said you shouldn’t throw away recognisable car names you’ve invested time and money on, badge loyalty isn’t all it was in the car industry. Ford played around with the Escort name for a couple of years including a saloon car in China, but Focus was where its heart lay and now even that car is headed for the scrap heap.

My father’s family came from Essex and Ford is the heartbeat of the county, so I suppose I am a Ford man at heart, particularly performance Fords. I love the angry sound of their exhaust, their underdog, blue-collar cheek, the control response and the handling, which in part was a reaction to those Mark V ‘never again’ Escorts and the responsibility of a great line of engineers recruited by Richard Parry-Jones, the Welshman who led the revitalisation of Ford’s cars, who died in 2021.

Escort has a long and convoluted story and it’s one I feel part of. And if those last front-drive Escorts weren’t the finest of machines, if you want to see why people pay so much for the early cars then have a look at the coverage of the 1982 Circuit of Ireland rally. This Easter weekend international rally was something of an end-of days for the rear-drive Escort. With the Mark III to sell Ford had dropped official support for the team, but these MCD RS1800 ‘Black’ Escorts were, as reigning world champion Ari Vatanen recalled: “the ultimate Escorts… We rallied it in 1982 and I don’t think we really won anything but we were very, very fast.”

Powerful certainly, but out gunned against the distinctly on form Jimmy McRae and Henri Toivonen in the Opel Asconas and his friend Hannu Mikkola in the warbling, chattering works Audi Quattro, Vatanen’s fire-spitting Escort looked almost too softly sprung for the narrow and slippery Irish roads, but then you realised just how fast he was going.

And I was there in ’82, watching one of my all-time heroes dancing that amazing car down the hedge-lined lanes, with the Cosworth engine howling its angry defiance against the world in general, a bit like Wilko Johnson’s chopping guitar riffs with the Feelgoods on Canvey.

All Essex attitude and all the better for it…

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage for daily news, features, interviews and buying guides, or better still, bookmark it.