In the 1980 movie Rising Damp, based on the successful TV sitcom, the Rigsby character played brilliantly by Leonard Rossiter, drives a battered red MGB with a primer-grey front wing. That car sums up everything we know about Rigsby; unattractive, unreliable and the hood falls off when he is trying to impress Ruth Jones (Frances de la Tour).

By the time of the Rigsby’s denouement in his MGB, the monocoque sports car was near the end of its life after a production run of 18 years with over half a million built. You don’t get an 18-year run like that for any old rubbish and the MGB wasn’t, so perhaps it was the sheer ubiquity of the thing which left some folk holding it in such disregard, or was it something else?

I felt very disdainful when asked to run errands in the MGB works hack back in the early Eighties when I was spannering my way through college at a classic-car restoration business. It was a bog-standard unexceptional model in navy blue, with chromium-plated bumpers, wire wheels and a rather tatty hood – a bit like Rigsby’s.

Yet here was a revelation compared with my Triumph TR4, my Ford Cortina GT, my Mini Cooper or indeed most of the old cars I’d driven up to that point. For a start it handled, the wheels stayed (mostly) on the ground through a bumpy corner, the doors still opened if you parked it on a kerb and it felt good to drive in a way that few contemporaries managed. It started, stopped, the hood still worked and was much easier to furl in a rain storm than my TR’s, and there was room for me, my girlfriend and my dog. At the time I was sniffy about the engine displacement of a mere 1.8 litres, but I’ve since learned that there is a substitute for cubes. Around the roads of Norfolk, it was sheer delight with its hollow roar from its four-cylinder B-series engine, the clickety gearbox with its swooshing Laycock de Normanville overdrive and the flickering Smiths instruments. It wasn’t fast, but it was nimble and fun and I came to love that car, so much so, I serviced it and even ordered it a replacement hood.

So where did the MGB’s reputation as brown Windsor soup on wheels come from? Moreover, 60 years after it was first launched, is it possible to reassess this polarising best-selling sports car? Let’s see.

Certainly no one at MG headquarters in Abingdon thought the MGB would turn out to be quite the sales success it proved when the company’s chief engineer Sid Enever and general manager John Thornley first started thinking about a replacement for the MGA. That car was a simply beautiful creation based on a pontoon-styled TD Le Mans car for George Philips which was penned by Enever. In seven years of production from 1955 to 1962, the MGA sold an unprecedented 101,801 models, yet it very nearly didn’t get made. Leonard Lord, BMC chairman rejected it when he first saw it, preferring instead to place his sports-car chips on the two-week-old deal he’d signed with Donald Healey for the Austin Healey series of models, and delaying the MGA’s launch for two years. It wouldn’t be the last time that MG was to fall victim to politics and play second fiddle to a rival.

Development of the MGB had begun in 1958 four years before its ’62 launch and the submitted design was devised by Enever and styled by Don Hayter with a bit of help from Pininfarina. Its steel monocoque structure had been tried on the 1953 ZA Magnette and also rivals the Austin Healey Sprite and the Sunbeam Alpine, but it’s not the work of the moment to design an open-top monocoque and MG’s was a good one. Other than that, the mechanical layout underneath was highly conventional and mend and make-do. While a V4 engine had been proposed, in the end the MGA’s trusty B-series was stretched to 1,798cc with a four-speed manual transmission, and the proposed independent rear suspension was dumped in favour of a cheaper live rear axle on leaf springs and a rather heavy but effective wishbone front suspension derived from that of the Y-type saloon.

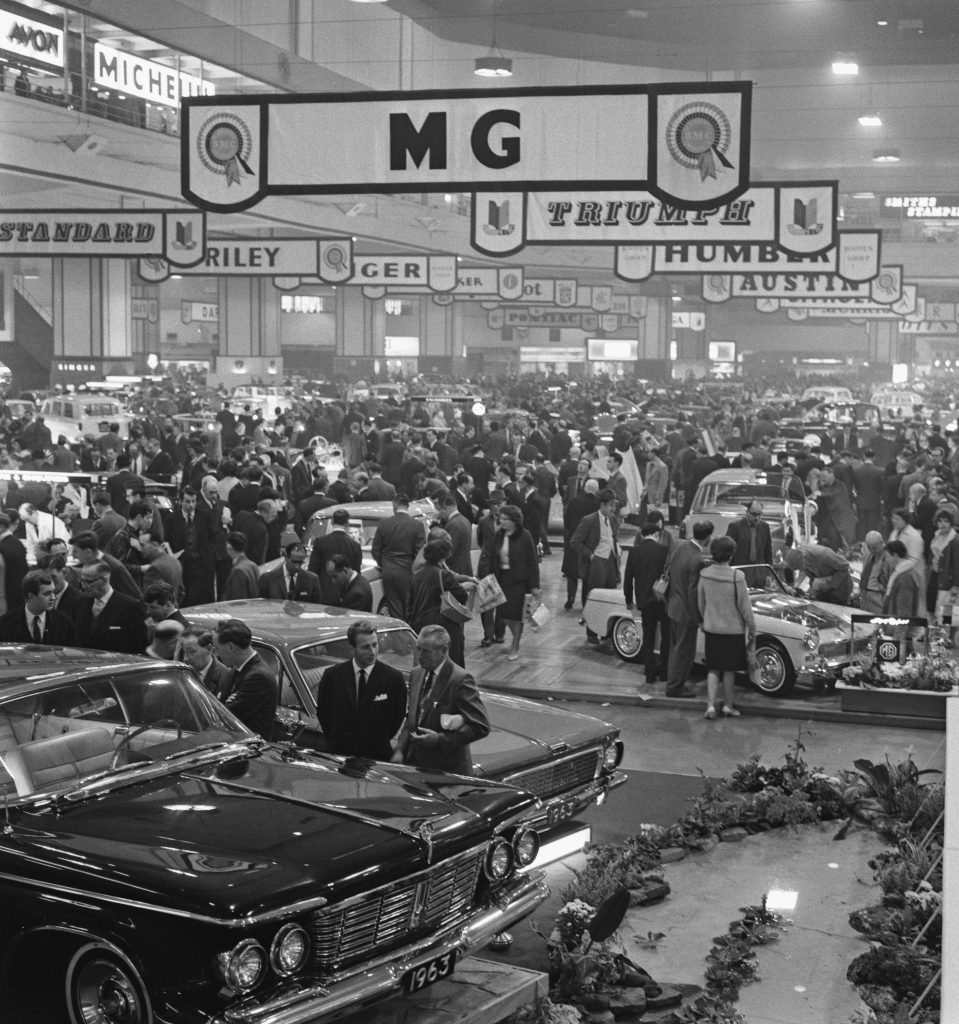

Wildly underrated by which ever company owned them, MG’s engineers were very good at their jobs and just three prototypes and eight pre-production cars were all that were needed to develop the new car. General Manager Thornley single handedly saved the project by signing a brilliant if ultimately expensive deal with Pressed Steel to produce the body/chassis and the first car was shown to the press on 20 September, 1962 on the preview day of the Earls Court motor show. One of the exhibits was a car split down the middle (maybe that’s where Damien Hirst pinched the idea from) to show the inner workings and how different it was from the MGA. Pathe News displayed an unerring ability to miss the point with its news reel of the ’62 show, which showed the MG 1100 saloon and not the MGB, though you can see another bisected motor show MGB (a 1965 MGB GT) at the Gaydon motor museum.

Generally, the press loved it and at just £950, well they might. The redoubtable deer-stalker hat wearing John Bolster, racer and technical editor for Autosport magazine, wrote: “The world of the sports car is changing fast. We used to admire the type of two seater that was all engine and performance and precious little else… A sports car must still have the superior performance and handling qualities, but is now expected to have all the creature comforts of a luxurious saloon, which means that noise, vibration and hard suspension are out.

“Such a car is the MGB…”

Sales were strong, particularly in America where three in five models ended up. There followed a series of improvements and developments (not all of them welcome) from Abingdon such as the better rear axle, the replacement of the aluminium bonnet with a steel item, an overdrive option, an automatic gearbox option, a six-cylinder engine with the 1967 MGC – but the most important life line the little car could have had, the Rover Buick V8 engine in the 1973 MGB GT, was five years too late. It was also launched in the middle of a fuel-price crisis and only sold in the UK and not in America where it would have been popular, but an unfavourable exchange rate would have made it even more expensive than the £2,294 it cost at launch compared with the £1,547 for the standard MGB.

Safety regulations in the US had turned the post 1974 MGB into a rubber-bumpered, high-riding monstrosity and besides, 18 years is a long time, the market changed and overtook the MGB, which was simply getting old and outclassed. Cars such as the Datsun 240Z, even the Triumph TR7 were seen as better sports cars, though in the latter case, what on earth were we thinking?

What went wrong? The late and much-lamented motoring writer Brian Laban in his book MGB The Complete Story says it wasn’t complacency since there was never any shortage of plans and proposals to develop and replace the MGB, in fact Enever and Thornley thought the original MGB wouldn’t last more than six years and were planning its replacement at its launch in 1962. Laban reckons it was more the politics and mega mergers of the British motor industry at the time (MG had disappeared into the corporate giant British Leyland in 1968 and horrible blue Leyland badges sprouted on the MGB’s wings), which together with the infamous 1973 Ryder Report, left little Abingdon out in the cold.

Keith Adams of aronline blames management, specifically Leyland boss, Donald Stokes who seemed to have in-built bias towards Triumph and torpedoed the MGB’s replacement the EX 234, and Michael Edwards who excluded MG from his plans and closed the loss-making Abingdon just after the 1979 50th anniversary of MG cars, which left the old 410,000sq ft site for sale and the famous octagon marque as a footnote in history and a badge on the back of some desperately ordinary saloons. In fact, Edwards later admitted he regretted the decision and vastly under estimated the strength of support for MG – what is it about fine words buttering no parsnips? It was left to enthusiasts to keep the marque alive, although Rover capitalised on the availability of replacement shells to bring us the 1993 £25,000 RV8 and then the little MGF of 1995 raised hopes for the marque, but again corporate shenanigans gifted the MG name ultimately to SAIC of China where it now lives on the back of a series of family SUVs and crossovers. What an end to Cecil Kimber’s legacy.

All this gives the poor MGB an almost unbearable poignancy about what could have been, but why does the car remain simultaneously so polarisingly appealing and naff? The baby-boom beard-and-bobble hat brigade hardly endear it to a younger, cooler audience, but then look at a really original car without the club badges and junk cluttering up the front, or for that matter one of Abingdon’s Frontline Development’s genuinely thrilling conversions on an MGB or a B GT with new engines, transmissions, reworked suspensions and beautifully trimmed cabins. Neither of those cars could be considered naff in any way.

Tim Fenna of Frontline Developments agrees that the MGB gives off mixed messages, but at heart he says: “the MGB is an affordable, approachable, solid and reliable sports car which has a huge popularity.” He also says that while Stokes might have had a Triumph bias, Abingdon and Canley where Triumphs were built were similar “craft and enthusiast driven factories” which could have survived “but were killed off by the bean counters”.

And therein lies the rub. MGB says so much about our past it’s hard to divide that from the car. In the end, though, I’d rather think of that Sixties navy-blue, chrome-bumpered model parked by a sun-lit Norfolk dyke with a picnic in the back than the smirking Seventies bosses with their helmet hair playing chequers with famous old car makers and their proud workforces.

It’s just a matter of perspective, really; you’ve nothing to lose but your beard and bobble hat.

Win this 1978 MG BGT

To celebrate the launch of Hagerty Drivers Club, we’re giving away this 1978 MG BGT! To win, please submit your entry using the button below.

Read more

Buying Guide: MGB Roadster and GT (1962-1980)

This electric MGB roadster is a breath of fresh air

Tom Cotter meets an MG collector on a mission

Very good article indeed, that. You can have a lot of fun in an MGB, and it was an honest sales and sporting success. Only thing I don’t agree with, having spent a weekend in one the rubber bumper model was not as bad as made out.

Thank you Michael. Point taken and I should admit here that my nephew owns a converted rubber bumper MGB which has been lowered and has chromium bumpers and he loves it dearly. The major issue with that car is it is jaffa orange! All the best, Andrew

Good article. FWIW, the car in the Earls Court photo is a Midget, not an MGB.

In the US the MGB was a great success. My parents bought a 1965 in my mother’s choice of Iris and I bought it from her in 1974 when I turned 16. I still drive that great little car, and never knew that it was looked down upon until I met some Pebble Beach people… but it seemed mine looked to them as the exception to it being the ‘ quintessential British POS’ to paraphrase whichever Pebble Beach head said that. Solid, nice handling, simple, and very attractive it seems the best car of the 60’s in the price range with the next one up being the E-Type. Monocoque makes all of the difference and TR’s and Healeys just aren’t in the same class, the MGB selling half a million and with so many Ford and Chevy small blocks being dropped in safely, its legacy isn’t the only thing more than solid.

Dear Mr McMillin, What a lovely story. Wow, an MGB at 16! We don’t get to drive until 17 in the UK and most young folk end up with something very old and venerable (read knackered). All the best, Andrew

I owned and loved two of them, a Mk1 1963 with pull door handles and an awful two-part hood frame, then a 1970 recessed grill, BMC/Leyland hybrid (it had BMC badged seat belts and those blue Leyland wing badges). Both suffered from severe rot, the latter after just 9 years! Miraculously both are still on the road today AMC383A & MCO100H.

I waited until I was 49 to buy an early ’74 chrome bumpered tourer (in the daring shade of Aconite!). Everyone warned me against it — including my father, who is a Healey aficionado. How wrong they were. It’s a wonderful car, particularly my well-sorted survivor. Handles well, feels fast, and fun to drive. They were so ubiquitous here in the States that they can get overlooked, but there’s also a reason over 500,000 were made. Every time I take the car out for a drive I get admiring comments, because everyone had one or knew someone with one. (One guy asked me last summer if I was James Bond – well, perhaps a post-Brexit James Bond on a tight budget?) BMC got it right in 1962; it’s a shame the company (and later BL) was incapable of investing in a winner and turning out a worthy successor.

Interesting article and their responses, thank you. My sad everlasting view is how the inspiration, designs, build quality, successes and future ideas by enthusiasts were so often ruined by management, which – I humbly suggest – was a constant British fault with our engineering companies, as your article illustrates, much like our aircraft industries. I’ve witnessed how men-in-suits both run then ruin a good business. No, not bitter, just regretful of what should have been still today. Sigh.

Very enjoyable article, thanks. A little while ago I read an interview with John Thornley where he said that the IRS was dropped for the live axle because the IRS setup they’d used didn’t handle very well. The change wasn’t based on cost.

Didn’t go Didn’t stop Didn’t go around corners. Uncomfortable, noisy. Unreliable. It had the lot.

Rubber bumper bashers are d*** h**ds! I own both a 67 and a 76, unless you are on race track you have pretty much the same performance and enjoyment. If you are that fussed about an inch in height it’s an easy fix. Each to there own, l enjoy both and the rubber bumper wich are actually plastic is a classic 70’s look and now becoming a collectors item wich it deserves after so many have been converted to chrome. The features l like on my 76 are a collapsible steering column, dual braking circuit, good safety features just for starter’s it’s so easy to make what ever changes you like as its still a MGB, so the snobbery over the later versions are nothing but subjective tastes of others that seem to dictate a nonsense elitism.

I’d always had a penchant for MGBs, having seen and ridden in a few before I was of driving age myself. I bought my first one brand new in 1973, a Blaze/Navy Tourer. As an eighteen year old kid still living at home, I was in high cotton!

Over the next twenty-seven years, I owned a succession of (16 different) MGBs & MGB GTs, driving them almost exclusively, day in/day out (in 1978, I bought an Austin-Healey 100/6 2-seater, which I still own today).

In October 2000, I left my last three “good” MGBs (running/driving/insured, etc., a ’68 tourer, a ’71 GT w/Buick 3.8 V6 & a ’74-1/2 GT, with my ex-wife as part of our divorce settlement. I kept only the half-restored, partly reassembled Healey.

After a twenty year hiatus, in August 2020, I was offered a very rusty, though extremely complete and original, 1967 MGB GT. It’s first owner was a USAF Captain and had purchased it in England for “personal export” to the USA. He kept the car throughout his active duty in Germany through 1988 (according to its logbook). The last air-base/DOD parking sticker on it is dated 1995, so clearly this was a beloved vehicle! I feel this car and its history deserves to be preserved; it’ll be a long road with zero financial gain I’m sure, but my intention is to return it to its original “as delivered” specification (BRG, wire wheels and 3-sync w/overdrive).

Long live the MGB!

Long live the MGB enthusiast community!

Re Sean Fullerton’s comment. Sean, I guess the MGB must have been a poor Car.

Let’s face it, it only lasted 18 years in basically the same form, sold over half a million units

and has one of, if not the biggest, following / Club and parts support of any British Classic.

Guess MG Owners don’t know much about Classic Sports Cars. Be very interested to

know just what you feel is a good, VALUE FOR MONEY British Classic Sports car !!

Good looking and ticking a lot of boxes on paper but too characterless. The reason I believe the MGB is divisive is because it just wasn’t macho enough. Back then I didn’t aspire to own an MGB but opted instead for a Triumph TR3A followed by and Austin Healey 3000 and then a Daimler SP250 (and then children!)

Today I feel the same and liken it to the Mazda MX5.

Was the proposed v4 engine going to be an MG in house one or one from another manufacturer?