Even elbows-deep in the engine bay of a 1943 Willys, Kam Mann, the founder of the Indo-Canadian Jeep club, resembles a Bollywood lead: immaculate hair, mirror sunglasses, natty leather loafers. A club member’s Jeep has suffered a mechanical casualty on the drive to this car show in Langley, British Columbia, Canada, and Mann and several others are hunched under the shadow of the vehicle’s hood, rattling off diagnoses in their native language of Punjabi. It’s a situation familiar to anyone – and especially to anyone who grew up in India.

When you think of Indian car culture, you probably imagine a pearl-encrusted Rolls-Royce from the days of the Maharajas. Or perhaps funky little taxis like the three-wheeled Tuk-tuk or the Hindustan Ambassador – basically a licensed Morris Oxford that was built all the way from 1957 until 2014. But if you had to distill Indian motoring to one vehicle, it would be a Jeep.

From the 1940s until today, these trusty 4x4s work the farms of the Punjab and crawl up the ridges of India’s seven mountain ranges. Rugged and simple to fix, a Jeep is what every young person yearns for there. Sure, you might start with a motorcycle, but you save up for a Jeep.

Since the story of India’s Jeeps begins almost immediately after WWII, a thumbnail sketch of early Jeep history may be helpful. Asked by the US Army to supply working prototypes of a four-wheeled reconnaissance vehicle, Willys-Overland and the American Bantam company heeded the call. However, Willys couldn’t meet the Army’s deadline, and Bantam was too small to hit production targets. Ford was called in as well. The final production model was mostly Willys, but with a mix of attributes from all three manufacturers’ pitches.

Over half a million Jeeps were built during WWII, roughly 60 per cent by Willys and 40 per cent by Ford. After the war ended, there was of course a surplus, and some of that surplus headed to India. The fighting forces of India had distinguished themselves in WWII, and the country had undergone a huge industrial boom in the production of war material. It was becoming thoroughly modern, with self-government on the horizon. Some gaps in infrastructure still remained, however, and a Jeep was the perfect everyman solution. It could handle whatever Indian terrain could throw at it.

The first 75 Jeeps came over as complete knock-down kits (CKDs), direct from Willys-Overland export operations. However, beginning in 1947, Mahindra began producing Jeeps under license in Bombay. Originally in the steel trading business, the company’s executives correctly identified India’s growing need for rugged passenger vehicles and tractor manufacturing. Having started out with early CJs, today Mahindra produces eight SUVs, including something called the Thar, which looks almost identical to the Wrangler.

Though the beginning of the Jeep’s story in India is one of legal collaboration, there’s since been mild controversy. A couple of years ago, the corporate owners (then FCA, now Stellantis) of the Jeep brand sued Mahindra: Its side-by-side, the Roxor, looked too much like a Jeep. FCA won, but with a 75-year heritage of building Jeeps in India, it could be argued that Mahindra was merely applying the rule that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.

India’s love of Jeeps is spreading far beyond its borders. Many of the farms in British Columbia’s fertile Fraser Valley are run by multiple generations of Indian-Canadian heritage, and more and more people –many of them tech workers, doctors, and engineers – are immigrating from India to Canada. The Indo-Canadian Jeep Club, which Mann founded in 2007, has just twenty regular and active members, but the membership of its Facebook page is over 700 strong.

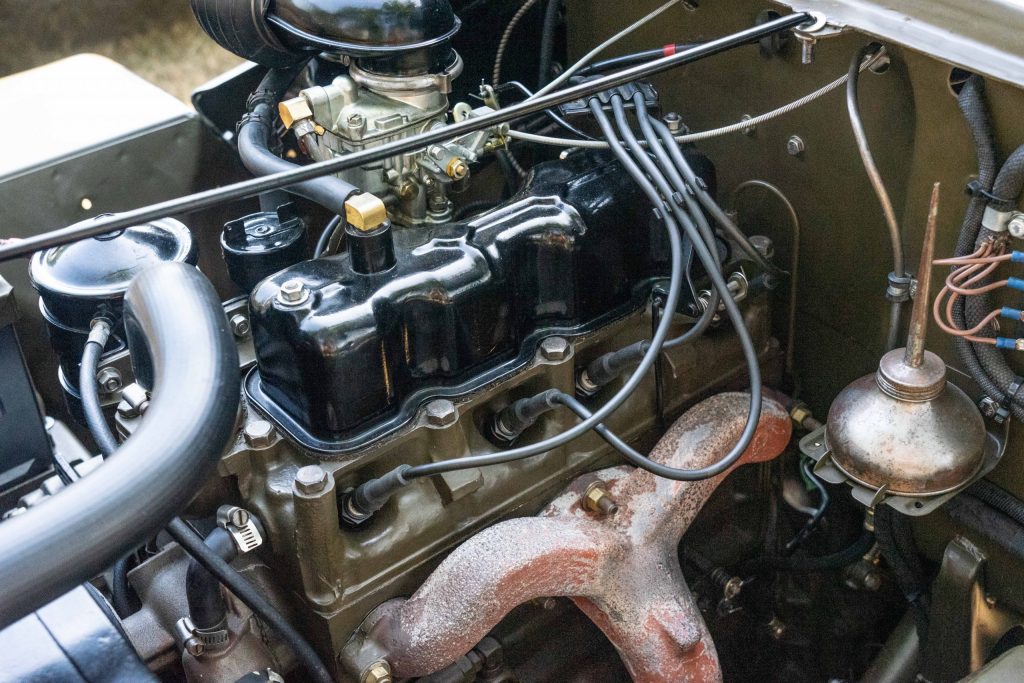

Back at the Langley Good Times Cruise-In, Mann and his fellow club members finally diagnose the ailing 1943 Willys. As they discuss the culprit – a condenser – dozens of curious onlookers of South Asian ancestry wander through the Jeeps assembled in Aldergrove, looks of recognition and admiration on their faces.

Almost all of the Indo-Canadian club’s Jeeps are WWII-era, but none of them are actually of Indian manufacture. Most of them weren’t even found in Canada. Mann, who has owned seven Jeeps, says that you can occasionally find early models like this 1943 example north of the border, but you’re more likely to find them in the United States.

“I always have one completed,” he says, “and another project on the go.”

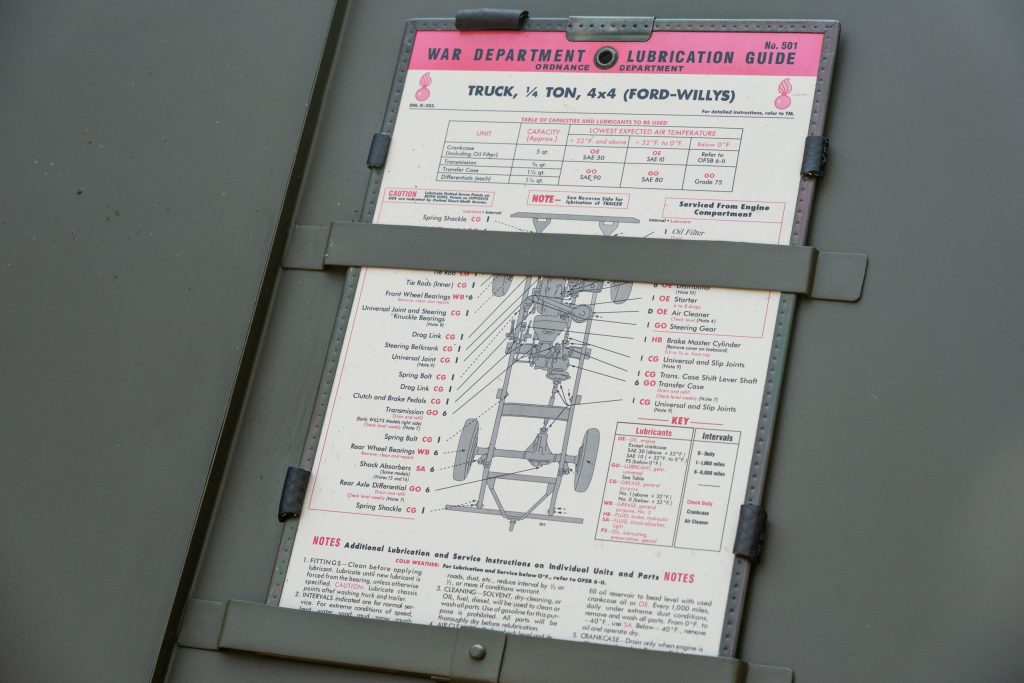

His 1943 Ford GPW is, like many of the club members’ rides, crammed full of cool details and accessories. The shovels and axes you expect, but two of the Jeeps are set up as full radio rigs, with functioning generators and period-correct gear. One club member casually remarks that he has a decommissioned bazooka in his trailer.

All the Jeeps were driven to the show – minus the stricken 1943 that everyone’s working on, which was towed in. Mann jokes that one of the other club members, Romy Swatch, has all the Jeeps (at least seven), while Mann has all the Jeep parts. As the club founder, Mann has allowed his home to take on the role of the club’s hub; members will often pop over to work on their Jeeps or to ask technical questions.

They are an enthusiastic bunch, and their enthusiasm is infectious. The small hill the club has staked out for itself is a major hit with younger visitors to the show. Who doesn’t like a kitted-out U.S. Army Jeep? The onlookers are probably thinking more along the lines of G.I. Joe. But if they knew the backstory, they’d recognize this grouping as an outpost of India’s heritage.

Hello

I have a 1953 Willy’s CJ2A for sale. I was speaking to some gentlemen in June at Heritage Park on Father’s Day. One of the gentlemen seemed interested so I am reaching out as I’m not sure if he has the correct phone number. I just want to know if he or anyone in your club would be interested in the keep. Thank you for your time.