Editor’s note: This story was first published by Hagerty US. Given the topic, we felt it would be a great talking point for followers of the British car industry.

Both cars were developed to address the same needs, both cars were the products of gifted engineers, both were praised by the motoring press when introduced, and both had success in motorsport. Yet only one of them sold more than five million units, is a British icon, and has a passionate worldwide community of fans. The other sold fewer than 1/10th that number, is often considered obsolete for its day, and was a financial failure that led to the demise of its maker. The cars in question? , Yep, you guessed it – the Austin Mini and the Hillman Imp.

The Imp was the Rootes Group’s attempt to address many of the same issues that Austin’s Mini was meant to solve. In the mid-1950s, Britain was still rebuilding after World War II and there was a burgeoning demand for inexpensive personal transportation. The microcars popular in the ’50s were not really up to the task of being family vehicles. In the wake of the 1956 war between Israel and Egypt, which temporarily closed the Suez Canal to oil shipments to Europe, fuel economy became preeminent. The trick was coming up with a car big enough to fit a family, yet small enough to be fuel efficient.

There is a fair amount of confusion and misinformation regarding the Imp. While many accounts portray the Imp project as a response to the Mini, in fact, engineer Michael Parkes’s team at Rootes started work on the Imp before Alec Issigonis started drafting what would become the Mini, and the two men actually worked together at Humber in the early- to mid-1950s. While Issigonis went on to knighthood, it’s likely that Parkes was at least Sir Alex’s equal as an engineer. He certainly had an impressive CV.

It’s also not unusual to see the opinion that the Imp was technologically obsolete when introduced, most likely because of its rear-engine configuration, in contradistinction to the Mini’s modern transverse-engined, front-wheel drive layout. That opinion ignores the fact that in the early 1960s, the Volkswagen Type I, or Beetle, and also rear engined, was one of the best-selling cars in the world.

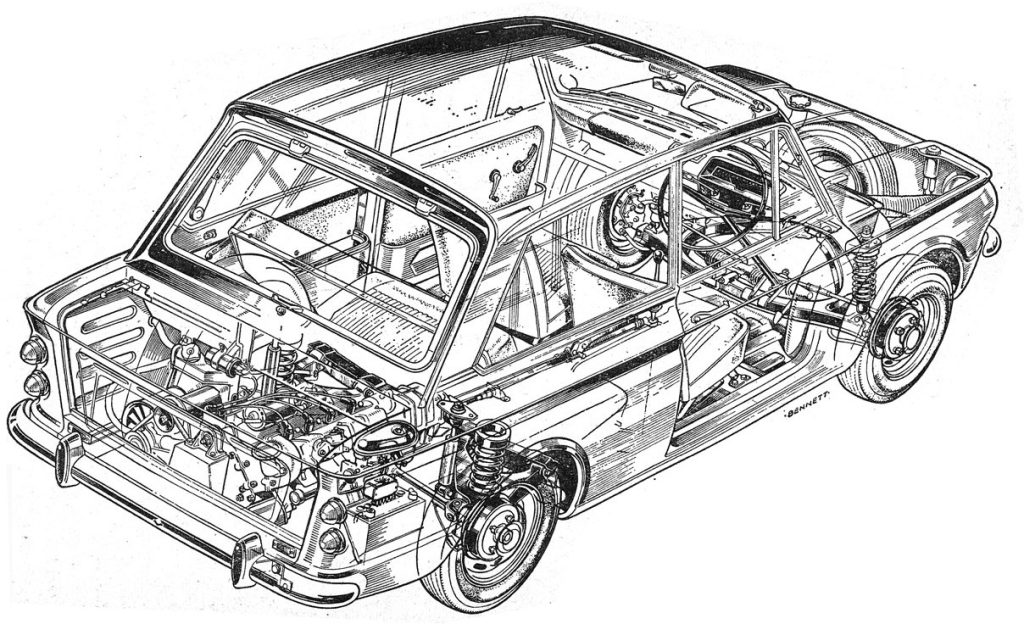

Furthermore, it could be argued that the Imp was more technologically sophisticated than the Mini. The Imp rode on coil springs while the Mini used rubber springs that would deteriorate over time. The Mini’s crankcase was shared with the transmission. That meant the gearbox was lubricated with engine oil, not 90 weight gearbox oil, and at the same time the gearbox wasn’t properly lubricated, the gears were chewing up the polymers in the oil, reducing the quality of engine lubrication. The Imp had a purpose-built transaxle developed internally by the Rootes group, with proper synchronisers, unlike the Mini’s “crashbox” transmission.

As for the engines in the two little cars, the Mini was powered by the same relatively old and primitive “A-Series,” all-iron, pushrod engine used in the Austin Healey Sprite and MG Midget, while the Imp had an all-aluminium, overhead cam engine with a legitimate racing heritage. Sometimes called “a poor man’s Porsche,” the Imp had a rear suspension that featured semi-trailing arms at a time when Porsches still had swing axles.

While the original Mini went on to sell over 5 million units, staying in production for almost a half century, the Imp sold a fraction of that amount, less than half a million cars, before it was discontinued 12 years after being introduced. Many histories attribute the demise of the Rootes Group, which was bought out by Chrysler in 1967, to the financial problems associated with the Imp.

So what went wrong? The BBC once described the Imp as “the wrong car built at the wrong time by the wrong people at the wrong place.”

The Rootes Group, which made Humber, Hillman, Singer, and Sunbeam cars, along with Commer-branded trucks, was considered by some to be the General Motors of the United Kingdom, a large, relatively conservative company with a range of brands that were not noted for style or performance but rather staid stolidity.

The mid-1950s, particularly after the Suez crisis, saw the introduction of a number of small cars for the British market from Ford, Triumph, and Vauxhall so Rootes started working on its first small car. The original prototypes were known internally as “Slugs” because of their relatively formless shapes, and the rear-engined cars were powered by air-cooled twins, causing Rootes managers to tell the engineers to go back to their drawing boards, thinking the prototypes were too much like the microcars that were proliferating in Europe at the time.

The revised design brief called for an affordable, fun-to-drive four-cylinder car capable of carrying two adults, two children, and their luggage, and the project was given the official internal name of Apex. Michael Parkes was the project engineer and Tim Fry the coordinating engineer, and the two worked under Peter Ware, Rootes’ recently promoted technical director. The new small car would be a challenge as the company had never built such a thing, while also lacking a suitable engine and transmission, a factory to build it, or the money to pay for it all. People may have thought of Rootes as the British GM, but the British car maker didn’t have nearly the resources that the Detroit automaking giant had at its disposal.

To finance things, Rootes approached the British government for a loan. There’s an old Jewish rhyme regarding philanthropy: “The one with the mei’ah (100) gives the dei’ah (idea).” A contemporary vernacular version would be something like “the one with the chequebook decides how things will go.” Rootes needed a factory, workers, and money. The UK government agreed to provide the funds but insisted that the new factory be used to boost employment in an area that needed jobs. In this case, it was near Linwood, Scotland, hundreds of miles from Coventry – the heart of Britain’s car industry, where Rootes was headquartered.

The Scottish shipbuilding industry had shrunk and the government was hoping the new facility would employ about 6000 workers. Unfortunately, the local pool of workers had no experience working in an automotive assembly plant, as well as having a history of labour unrest. Any assembly plant start up is going to have teething problems, particularly if it is building an all-new vehicle. Adding the particular problems with locating the factory in Scotland only exacerbated things and may have doomed the Imp from the beginning. Delays in development and building the factory also meant that the Imp was not introduced until 1963, years after the Mini came to market.

In addition to an all-new assembly plant, the government funded an advanced die-casting foundry to make the engine blocks and head, and a new Pressed Steel stamping plant for the body panels. Locating the facility 300 miles from Rootes’ main factory at Ryton-on-Dunsmore, near Coventry, also meant logistical problems because suppliers were far away, as was the engineering team at Rootes. Engine castings had to be shipped via train from Scotland to the Ryton plant for machining and assembly, and then shipped back to Scotland for installation in the cars.

To start with, the Apex project needed a drivetrain. Not having a four-cylinder engine suitable for a small car, the Rootes Group decided to go outside the group and buy one. At the time, this was not that unusual in the industry as many of the independent American car makers used engines supplied by Continental and Lycoming. Fortunately for Rootes, an appropriate engine design was already in production in the UK.

Fires started by German bombs during World War II’s Battle of Britain convinced British authorities of the need for portable water pumps for firefighting. After the war, in 1950 the Ministry of Defence requested bids for a fire pump that put out twice the volume of water as existing pumps, but weighed half as much.

In the postwar period, the Coventry Climax company made fire pumps as well as marine engines and industrial forklifts. With the help of noted engine designers Walter Hassan, whose credits included the Jaguar V12, and Harry Mundy, the engineer behind the Lotus Twin Cam, the company developed an all-aluminium inline four-cylinder, with wedge-shaped combustion chambers, cast iron cylinder liners, three main bearings, and a single overhead camshaft to operate the valves, magneto, and mechanical fuel pump. The result was a 1020cc engine that put out an impressive (for the time) and reliable 36 horsepower at 3600rpm.

Climax got the MoD contract and put the engine into production, designated F.W. for Feather Weight. The racing community in England quickly caught onto the CC F.W.’s potential as a high-revving powerplant for motorsport, and in response Climax bored it out to 1097cc, and added a second carburettor, high-compression pistons, and a stronger crankshaft to produce the F.W.A. (A as in automobile) engine. It doubled the power to 72bhp and significantly increased redline to 7000 rpm.

The F.W.A. became a fixture in open wheel and sports car racing, and even found its way into a variety of road-going specials. An F.W.A.-powered Lotus 11 won the Index of Performance at the 1957 Le Mans 24 hour race, leading Colin Chapman to commission Climax to produce the 1200cc F.W.E. version for the original Elite, Lotus’ first road car.

Rootes contracted with Coventry Climax for an 875cc version of the F.W., with a new head and detuned to a 10:1 compression ratio for the road, to be made under license from CC by Rootes, dubbed the F.W.M.A. With a single carb, it put out 39bhp at 5000rpm. This Mk1 engine had some reliability and oil loss problems, so in 1965, the Mk2 version of the motor was introduced with stiffer block and head castings, and larger valves and ports. In 1966, the Sport version of the Imp was introduced with 998cc displacement, a hotter cam, two carbs, and headers, increasing power to 51bhp at 6100rpm. By comparison, the original Mini had a 850cc engine putting out 34bhp.

Regarding the Imp being obsolete when introduced, the F.W.M.A. engine was the first all-aluminium engine in a British production car and the first OHC production car engine in the UK as well. To fit the four-cylinder motor in a space originally meant for a twin, Parkes’ team canted the engine by 45 degrees, which created room to put the radiator, cooling fan, and water pump next to the engine’s sump.

While the Coventry Climax engine impresses, perhaps the Imp’s greatest technical feat was the transaxle, which Rootes developed internally, starting with a blank sheet of paper. It had an aluminium case, four forward speeds, and had synchros in all four gears, unlike the Mini. Gear changes were described as precise and quick, something that couldn’t necessarily be said about the Mini or VW Beetle. The result was a truly featherweight drivetrain. The engine and transaxle together weigh as little as 80kg, according to some sources.

Steering was via rack and pinion, and suspension was independent front and back, with coil springs and tube dampers all the way around. While the rear suspension was a sophisticated-for-the-day semi trailing-arm setup, helping to avoid trailing throttle oversteer known to rear-engined cars with swing axles, the front suspension did use swing arms, which don’t have nearly the problems up front as they can have when fitted to the rear suspension. According to one account, the rear suspension design came about after the design team had some kind of problem when testing an early, swing-axle equipped Corvair, on a tight corner.

No matter how they arrived at the solution, the layout worked well; no less than John Surtees praised the Imp’s steering and handling. Perhaps for cost saving, the rear suspension, while fully independent, used metal and rubber Rotoflex (aka Giubo) couplings instead of universal joints or constant velocity joints. One may scoff at rubber drivetrain components, but they were also used on the Lotus Elan.

Putting the engine in back meant lots of storage space up in the “frunk,” though nobody would have called it that 60 years ago. The rear seat folds down for additional luggage room, and in a novel feature, the rear window hinges like a hatchback to ease access to that cargo room.

While some considered the styling to be boxy and boring, in fact Rootes designers deliberately imitated the Chevrolet Corvair, thinking the American styling would appeal to younger drivers. With a long bonnet and short rear lid, and a tall, airy greenhouse with outstanding visibility, the Imp had a sporty look that was indeed impish. For a little car, it does stand out in a crowd of its contemporaries.

Total length was under 3.6 metres, half a metre longer than the Mini, though the wheelbases were close, 2082mm for the Imp versus 2036mm for the Mini. With little more than 700kg to carry around, the 39bhp Coventry Climax was adequate for the day.

While the development team wanted more time to fully fettle the Imp, already three years behind the Mini, Rootes decided to debut the Imp under the Hillman brand in May, 1963. Original list price was less than $1500 in 1963 dollars, which I believe works out to about £535 in 1963 pounds sterling (about $14,520 today).

Press reports on both sides of the Atlantic praised the Imp’s performance and handling. Sadly, all that praise didn’t last, as quality control issues started to increase. Overheating, water leaks, and blown head gaskets – partly the result of a lack of experience casting and making alloy engines, and partly the result of owners not maintaining those aluminium engines – gave the Imp a reputation for unreliability, as did deteriorating Rotoflex couplings. The assembly plant’s workforce had experience building ships, not cars, and like at many greenfield automotive plants with inexperienced workforces, quality suffered. The 1960s was also a period of great labour unrest, and strikes stopped production at the Linwood plant 31 times in 1964 alone.

Dealer attitudes exacerbated the Imp’s quality control problems. To begin with, Rootes Group dealers weren’t thrilled to be saddled with selling an inexpensive, low-profit margin car, and they were certainly not thrilled to do warranty work on a completely unfamiliar product that was unlike any of the other cars they were selling. Warranty service was impaired by a lack of parts due to continuing labour issues at Linwood, which also affected supply of new cars to those dealers that did want to sell them.

Marketing was uneven. Originally marketed as a sophisticated, advanced automobile, as sales declined Rootes started to sell it as a cheap economy car, on par with low-end European brands popular with the budget set in the UK at the time.

Through its multiple brands, Rootes sold a variety of mostly badge-engineered variants including the Sunbeam Stilleto, the Commer Imp Van, the Hillman Husky, the Singer Imp Sport, and others, as well as the fastback Singer Chamois Coupe, which had significant styling differences from the Imp sedan. Left-hand-drive versions were developed for export markets; in the US, the Imp was sold under the Sunbeam brand, with probably fewer than 5000 delivered, but enough that LHD models pop up for sale now and then on the other side of the pond.

Half of all Imp sales were achieved in the model’s first three years on the market. No doubt those sales were helped by rally and racing wins, including the overall title at the 1965 Tulip Rally. The Imp also won the British Saloon Car Championship three years in a row in the early 1970s.

While the Mk2 version addressed many of the Imp’s shortcomings, sales had already started to decline, and the saloon car championships didn’t help stem the slide. Although the Imp managed to stay in production for over a decade, by the time it was discontinued in 1976 with the permanent closure of the Linwood plant, total sales after 12 years of production were only about 440,000, including all variants.

Many consider the Rootes Group’s large investment in developing the Imp and building the car at Linwood to have been a major factor in the financial crisis that led to Rootes’ eventual takeover by Chrysler just four years after the Imp was launched. Certainly the Imp’s failure to thrive was a factor in the Rootes Group’s demise.

This article was originally posted on Hagerty US.

Read more

Join the Club: The Imp Club

Top 10 ‘poverty-spec’ cars

Our Classics: 1959 Hillman Minx

Interesting and balanced article but just to clarify all the sport variants and the Sunbeam Stiletto were still 875cc (51bhp) not 998cc (up to 90bhp dependant on specification) as this capacity was only available as a special option, generally for competition. There were a number of coupe models such as the Sunbeam Stiletto, Imp Californian, Singer Chamois Coupe etc produced some in single headlight form and some with twin headlights resembling the Corvair.

A Hillman Imp (NTB 312C) was my first decent car bought in 1968 replacing a very rusty Simca Aronde. I ran the Imp for three years. I had a love hate relationship with it. I remember the car was much quicker than a standard Mini at the time but was plagued with problems particularly water pumps, front suspension took a hammering with bent king pins and quickly deteriorating front shock absorbers. The Coventry Climax 875cc engine was lovely and very smooth, I was able balance a three penny coin (before decimalisation) on the rocker cover, engine running of course. I think I paid £370 for the car from used car dealer in Rawtenstall and sold for £250 three years later. It probably cost a small fortune to keep on the road.

The Coventry Climax engine was also used as the generator for the Rapier guided, ground to air missile system.

The Imp engine was DERIVED from a Coventry Climax engine. It wasn’t a CC engine, and was cast in various places, and machined in various others. The Imp didn’t kill Rootes : the government decision to only allow the factory to be built in Glasgow and using workers more used to ship building did, along with the rife Union led industrial unrest, strikes and poor logistics regarding the engine and transaxle machining being hundreds of miles away was downright stupidity. A great car marred by moronic decisions. Chrysler came along and further ruined the concept, with deletions and a lack of proper investment.

Good article, but again following a few of the usual assumptions. Their had been car production in Paisley before (Linwood is essentially an extension of this ancient town, which is not, nor never has been part of Glasgow) by Beardmore, who at one point were the biggest taxi cab producers in the UK. Paisley also supported aeronautical engineering (and still does – Rolls Royce), so not just shipbuilding, and was more famous as a mill town (er Paisley Pattern anyone?). The Pressed Steel plant produced bodies for Rover and Volvo (P1800, shipped from Grangemouth on the east coast of Scotland, so Linwood to Coventry a doddle in comparison) before Rootes took over. And strikes were endemic at that time (and as I write are becoming endemic again in the UK), not just in Scotland but everywhere. The plant also soldiered on following Chrysler Europe’s demise, being finally closed by the new owners, Peugeot (indeed I remember seeing new cars on the special delivery trains when a wee boy around that time). And Peugeot eventually closed all their UK plants. I still have an Imp, with at 400k miles on the clock and 37 different countries visited.

Iain,

I completely agree with what you say about ‘the usual assumptions’, the Linwood plant was not hampered by industrial unrest and logistics any more than other car plants at that time, of course it’s a fair distance between Linwood and Coventry, but they had a direct rail link [google, ‘the hilman imp railway express’ you will see photos of hundreds of cars on rail flatbeds] . Although some of the workforce were ex-shipbuilders, they were employed in semi-skilled labour with a wage that was far better than anything they had earned in shipbuilding, they were a happy workforce, so it was hardly the guys on the tools who cause industrial unrest.

Rootes encountered many production issues, and people I know who worked at the factory [drawing office staff] told me the middle management would manipulate production problems into ‘stoppages’ to avoid having to pay workers ‘overheads payment’ when these production stoppages halted the assembly line. It didn’t happen often, but the fact that it happened once encouraged a ‘them and us’ atmosphere.

The ‘Pressed Steel’ factory [located right beside the Linwood assembly line] produced car bodies for Volvo, Jaguar, Rover and also produced railway carriage body shells, with an excellent reputation for quality.

The assembly line workers could produce 60 cars per hour, but initially they were producing a car that had design errors which should have been fixed before production commenced.

It’s my guess, that if there was a ‘Japanese attitude’ used in the Rootes middle management, the Imp car would have been a far greater success story. It’s unfortunate, but British management skills back in the sixties were poor or non-existant.