Like so many inexpensive sports cars built by large automakers, the Toyota Sports 800 was based on the mechanical bits and pieces of a high-volume saloon. As Toyota’s very first sports car—an unknown leap for risk-averse management at the time—it had to be cheap to make. But rarely has the ratio of “humble pie origins” to “radical results” been so extreme. In fact, what became the truly wild Sports 800 started off as a derivative of the burlap-sack-basic P10-series Toyota Publica.

This radical transformation mirrored the exuberance of Japan’s 1960s economy, and it was that economic growth that led to the Sports 800’s creation in the first place. With just 3131 built from 1965 to 1969, the 800 wasn’t considered a success in its day, but it was a pivotal moment for Toyota. And although it was soon overshadowed on the world’s stage by the exotic, partially Yamaha-designed 2000GT of 1967, the two-cylinder “Yota Hachi” (Toyota 8) was an all-Toyota jam that paved the way for everything after.

The engineer and the Publica

That the Sports 800 turned out to be such an exotic-looking, uncompromising machine was down to the primary creative forces behind it: precision-minded engineer Tatsuo Hasegawa and eccentric ex-Nissan designer Shozo Sato. Their decisions produced a fantastic car, but one that was perhaps too hardcore for most buyers. It was also especially vulnerable to rust, and survivors are exceedingly rare.

Hasegawa is known today as the creator of the Toyota Corolla and Celica, but before that he was the Publica’s engineering lead. Cars were his second career, however. Inspired by a childhood encounter with a French Salmson biplane, his first love was aviation. Growing up poor after his father died young, he put himself through school and in 1939 earned an aeronautical engineering degree from Tokyo Imperial University.

He immediately went to work for Tachikawa Aircraft, spending the last two years of WWII designing the Ki-94 high-altitude interceptor. The war ended before the plane ever flew, and with aircraft development banned in Japan, Hasegawa had to look for new work. He joined Toyota in 1946, working his way up the engineering ranks until the Publica project came along.

The Publica grew out of a 1955 request by Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) for manufacturers to develop a cheap and durable “national car.” While this brief spawned many diminutive kei cars, Toyota had larger ambitions. Company boss Eiji Toyoda originally wanted a Citroën 2CV–like design, but front-wheel drive proved too costly, so Hasegawa and his team designed a no-frills rear-drive two-door sedan around a 697cc, 28bhp, air-cooled flat-twin and a four-speed manual.

How “no frills?” Early Publicas didn’t even come with a heater or a radio. Though the Publica was a success, it was understandably seen as too basic. Japan’s economy was booming, and during the time of the Hayato Ikeda government, GDP grew by 10 percent a year. Consumers could afford to demand more, and Toyota wanted a way for the Publica to accommodate them. To do so on the cheap, Hasegawa enlisted Shozo Sato to design a sexy concept car, the Publica Sports, for the 1962 Tokyo Motor Show.

The artist and the Sports 800

Sato was one of Japan’s most talented designers but also one of its most mercurial. He’d joined Nissan in 1937 and was the company’s first proper lead designer. He won Japan’s prestigious Mainichi Design Prize in 1956 for the 112-series Bluebird. An artistic wunderkind and hardcore car nerd, Sato was fond of quickly brushing up oil paintings of his favorite cars in the studio.

His talent often earned him a pass for his penchant for radical candor. In Nissan’s conservative culture, disagreeing with bosses was not normal, but Sato hated compromising designs or changing things for cost, and clashes were frequent. In 2013, Sato’s former underling, Isao Sano (lead designer of the Z32 300ZX) said that Sato once returned so angry from a meeting with his bosses that he was unable to light his pipe; his hands were shaking too much.

But Sato was also funny and self-deprecating, and those in his charge liked him despite his perfectionism. A heavy smoker, Sato was sidelined several times with ill health in the late 1950s, but he would routinely dispatch pages of detailed instructions from his sick bed.

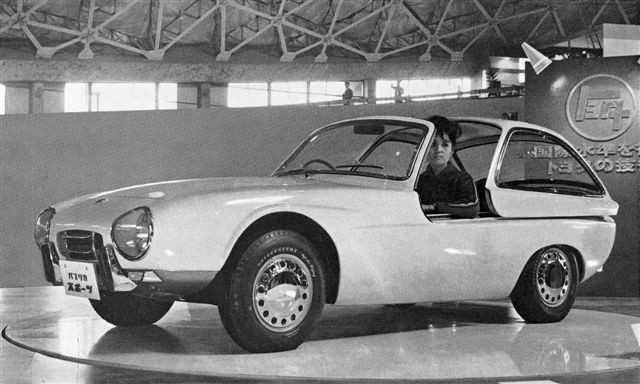

His health continued to fluctuate, however, and the clashes with management didn’t help. By the end of 1959, Sato was on leave again, and it was unclear if he even still worked at Nissan. By early 1961, he was “on loan” to Toyota. Exactly how he and Hasegawa connected isn’t clear, but Sato designed a sleek, space-age coupe for Toyota’s show stand, with an ultra-low beltline and a radical slide-back bubble top.

The proportions and details were gorgeous, the shape evocative of those by Bertone or Zagato. Showgoers absolutely loved the Publica Sports, and it was soon greenlit for manufacture. As is often the case from concept to execution, the car took three years to see the light of production, a process Sato played little role in.

Toyota vs. Honda

Several months before the 1962 Tokyo show, Honda showed the S360 roadster at its annual dealer gathering at the Suzuka circuit. The response was enthusiastic, but Soichiro Honda wanted to build a more substantial car that could be sold outside of Japan. Accordingly, Honda’s engineers upped the engine size from 360cc to 531cc and created the S500, which debuted just across the show floor from the Publica Sports concept. Both it and Nissan’s SP310 roadster were in full production by the summer of 1963, and Honda dropped the even-better S600 in 1964.

Against those competitors, the production Publica Sports would have to be good indeed, which meant some radical changes.

For more power and torque, the Publica’s flat-twin was bored out to 790cc. Costs could be kept in check by reusing the bigger engine on updated Publicas and MiniAce vans later on, but with twin carbs, the extra displacement, and higher compression, the 2U-B engine was good for 44bhp—the same output as the Honda’s engine but available at lower rpm. The Publica’s double-wishbone front suspension and rear leaf springs would carry over.

The big compromise made on the design side was the loss of Sato’s sliding top. It was simply too heavy, so it was deleted in favor of a targa top that kept the original silhouette intact. Notably, Toyota beat Porsche’s 911 Targa to market by several months.

To be truly competitive with the featherweight Honda, the Sports 800 would need to trim every possible ounce of weight. Here, Hasegawa’s aircraft expertise came in handy. The underlying structure of the unibody, inherited from the Publica, would be made of a thinner-gauge steel, and many aluminium panels were incorporated, including those of the targa top. A niche item with an unknown market, the Sports 800 would be built at Kanto Auto Works in Yokosuka.

The wafer-thin panels were easily banged up and had almost no rust resistance, but the Sports 800 weighed just 580kg when it went into production in early 1965. Aerodynamics helped the tiny twin hit 96 mph flat-out and made it fantastically fuel-efficient, which would eventually help it win races. It was a pure performance car—small, spartan, and speedy—but too extreme for most buyers.

Myth and mystery

Despite a price of just ¥595,000 (£592), pricier than a Publica by far but not particularly expensive, the Sports 800 never sold well. Deliveries peaked at 1235 cars in 1965 and sank to just 215 in 1969, a far cry from the 13,000 Honda S600s built from 1964 to 1966. Toyota hadn’t aimed for a blockbuster, but the results were disappointing.

Hasegawa’s next sporty car, the 1971 Celica, scaled down the Ford Mustang playbook for global markets and became an international hit. The enigmatic Sato, meanwhile, returned to oil paintings and watercolors, only now for the pages of Car Graphic magazine.

By the time the Celica began enjoying success, the Sports 800 was a memory. There had been one aborted chance for broader success, however: A total of 300 left-hand-drive cars had been built for Okinawa, and 40 of those were shipped to America for test marketing in 1965. Despite Datsun’s success with the Fairlady in the USA, Toyota’s dealers felt the Sports 800 was just too tiny for Americans. Amazingly, rather than ship the cars back, they were fire-saled. Most vanished.

In Japan, the Sports 800 earned a reputation for responsiveness and speed, but with so little protection from rust or from crashes, many went to an early grave in the 1970s. Parts also quickly proved to be a problem. With many special pieces made only by the Kanto factory, replacements were hard to find. Many cars were modified as a result.

The survivor

James Kolafa had always liked the Sports 800 but considered them out of reach. In 2019, he bought a Mazda AZ-1 from a JDM importer friend, Adam Chovanak. The pair got to talking and eventually decided to find the Toyota. “They’re charming, beautiful, and rare, but expensive,” says Kolafa. “So the plan was to split the cost of buying and importing one, and then sell it after we’d experienced it.” The search took three years.

After bidding on and losing five other Sports 800s (one of them twice), this silver car came up for auction in Nagoya, Japan, with a filthy interior and worn-to-the-belts tires. However, the inspection sticker was current. “We were happily surprised that it’s totally rust-free,” Kolafa says, “but we also discovered that it had been much modified in the 1970s.”

When the car arrived, it had dirty astroturf carpets, beneath which were layers of red and black carpet and some 1960s floral print fabric. The car had once been painted white, then lime green, then silver. The blue leather upholstery replaced red material, which replaced the original black. The most interesting factory option? The blue petrol–fired heater just aft of the engine, complete with its own fuel pump. “I’m kind of terrified to use it,” Kolafa says.

But the rest of the car, Kolafa argues, is loads of fun—and exceedingly well-built. “For a tiny car, it feels very substantial. All of the parts, like the doors and switches, feel like an ultralight version of Mercedes quality. The shift linkage is amazingly tight and precise.”

The car’s lightness means similarly sharp handling. “It has a directness, almost like it’s talking to you,” Kolafa adds, “and the responsiveness doesn’t change at higher speeds.” The car’s slippery aerodynamics also mean that it sounds and feels about the same at 55mph as it does at 80. “You’re running out of steam by then, but it’s very stable.”

The worn tires and wheels were soon exchanged for new rubber on SA22C Mazda RX-7 wheels. “They look just like Campagnolos and they were the exact right size,” Kolafa says, noting that proper Sports 800 wheels run $1300 (£1045) each. The prospective costs of keeping the Sports 800 aren’t on the cards for Kolafa, who puts more value on experiencing a car than keeping it forever.

“I also don’t have the space to store everything I want, so trying out lots of [cars] is more fun,” Kolafa says. “Now I’ve had this experience, and it’s on to the next oddball.”

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage for daily news, features, interviews and buying guides, or better still, bookmark it. Or sign up for stories straight to your inbox, and subscribe to our newsletter.

I had one in the UK. A white 1968 regd convertible. SMK 47F, where are you now?