London Taxi Company’s bankruptcy stirs memories of a special cab

News that the London Taxi Company is in bankruptcy, and the future of the city’s black cabs is in doubt, is almost as bad as the disappearance of the traditional red double-decker buses from the capital seven years ago. All more than 40 years old, the Routemaster buses had been designed to last indefinitely, rather like a Volvo 240.

London’s black taxis date back 110 years, and were horse-drawn hackney carriages before that. Like New York’s Checker cabs, they were specific to their city. However the present manufacturer is partly owned by Geely of China (some cabs were built in Coventry, others in Shanghai), and a string of losses since 2007 caused the Chinese to pull the plug. Modern Mercedes-Benz Vito and Nissan NV200 minivans threaten to replace the taxis and one suspects maintenance costs will skyrocket. As you can imagine, London’s cabbies are not happy.

Wherever you live in the world, chances are you’ve seen a London taxi. From 1949 onwards most have been of two types. The Austin FX3 was introduced in 1948 and was the last principal design to have an open platform beside the driver, for kerb-loading of luggage. In general, its profile appears to date from the late 1930s, with separate fenders, freestanding headlights and running boards. Austin introduced a 2.2-liter diesel engine in 1954, which upped the mileage from 12-15 mpg to 36 mpg, and by 1955, diesel cabs outsold petrol ones nine to one. In all, 7,267 FX3s were built by the end of 1958 and about 700 were exported. The 10-year lifespan is important because the very strict safety test required at the end of that time essentially retired all cabs from Central London service.

The FX3 was replaced by the FX4 in 1958, which is the square shape most people immediately recognize. This now had four doors and could carry five passengers. A Borg-Warner automatic transmission was offered but most cabbies found a stick was more economical. About 75,000 were built, and Nissan diesel engines powered the last Fairway models, which were replaced in 1997 by the present rounder-bodied TX series, now uprated to the TX4.

My first inkling there might be a taxi in my future was when a friend stumbled into a building due for demolition (or drastic remodeling, I forget which) in Vancouver, Wash., across the Columbia River in 1987. In a corner of the basement was a 1949 Austin FX3, supposedly a refugee from Los Angeles movie work. The paint was flat, it was missing the front bumper and the driver’s seat cushion, but it was relatively straight and not rusty. $900 changed hands and we towed it home. Somebody had painted “TAXI” where the roof light should have said “FOR HIRE” and the taximeter was a wooden replica, (which certainly sounds like Hollywood), but a half-day’s fiddling had the two-liter, four-cylinder engine running. The brakes were mechanical, the tires OK, the lights worked, but all the chrome trim was missing from the grille.

While I pondered how to find the missing parts, word came of another FX3 sitting in a front yard in Southeast Portland, close to the Horse Brass British pub. I beat feet over there to discover a 1958 diesel FX3, which had been used to transport tourists around Portland’s Old Town, as Stumptown Tours. It was rusty but complete, and it ran. Unfortunately it had no brakes and had been summarily parked. How could you have no mechanical brakes, I wondered? Its arrival was timely, as my 1949 taxi had died, despite having spark and fuel. Not good.

I drove the 1958 cab home with brakes that seemed unable to actually stop the car at all. Lots of pedal, no effect. The next move was to get a shop manual and figure how to work on two cars in the backyard, as winter approached. The answer was simple: I quit dragging my feet and moved from a wonderful 1895 Victorian, with a chicken coop for a garage, to a modern subdivision with a three-car garage. There I took both cars apart and assembled the best combination of the two (over about two months, let me add).

Luckily, both cars had built-in jacks, so that I could pull all the wheels and compare the brakes. I discovered that it was a rod system; the back-plate to each wheel had a cone that forced the shoes apart, when the rod was pulled by the brake pedal. In the diesel car, somebody had put the cones in backward, and progressive panic stops had stretched the rods, so they no longer had effective leverage. Luckily I had all the parts I needed in the other car. I also discovered that the dashboard was hinged at the bottom, so if you needed to replace gauges or switches you unscrewed the top of the dash and it tipped back into your lap. Other nice touches were adjustable tie-rod ends, which still seems a brilliant idea. I also learned that the extremely tight turning circle only applies to right-hand turns. Think about it, you’re at the left kerb and you want to make a U-turn…

About this time I went to England for my sister’s wedding and stopped by the London General Cab Company, which had owned my diesel cab #271 when new. The managing director was charming and friendly, but reminded me that at the very latest, my cab was retired in 1968, 21 years before, and no, they had no spares. “So how many miles has it covered?” I asked him. “We would have double-headed it for 10 years,” he said, “one driver in the daytime; one at night. Apart from repairs and service, it was on the road all the time. I’d say 750,000 miles, at least.”

The best fenders and doors came from the older car and were repainted. Assembling the diesel model I discovered that the radiator was mounted half an inch further forward and the bonnet came up short. Who knew? Pieces had to be juggled. Road tests disclosed that the mechanical brake adjustment was incredibly sensitive to balance, as I did a quick 360-degree spin on a wet road.

Living further out of town revealed a problem in commuting. My cab was flat out at 60 mph, at which point the engine was roaring, and I was cramped in my single-seat cabin with no heater. At least I had a side window; pre-WWII cabs did not, in case the driver dozed off. An additional problem emerged. I could carry five people in the back, but I couldn’t hear a word they said, nor they me, even with the sliding glass division open. It was worse than being a chauffeur with a speaking tube, and I was reminded that London taxis had smoked rear windows and no interior mirror until 1960. The passengers were none of my business.

About this time, life intervened, and I got divorced. It’s amazing what you can fit in the back of a London cab; even my Siamese kitten, Sinclair, who tolerated me for the next 16 years. A friend stored my parts car and I drove my noisy diesel for about three years, as fuel prices started to climb. Eventually, driving by myself with no heater wasn’t fun anymore, and I sold both cars to George, another eccentric collector.

I ran into George at a swap meet about a year later and asked what he’d done with the taxis. “The parts car was turned into a drag racer, and the diesel cab I sold to a Buddhist monk in Tokyo,” he reported. “The monk didn’t have very good English, or a good sense of time zones, because a few months ago, I got a phone call at 4 a.m. ‘Need gasket set and pistons, engine blew up,’” he said.

One aspect of #271 lingers. The atmosphere in that cab was haunting: the unmistakable smell of leather, the period advertisements and rate tables. If you ever sit in the pitch-black bomb shelter in the Imperial War Museum Blitz Exhibit, you are surrounded by the voices of actors as people who were there. That old taxi was crowded with thousands of people who had hailed it. They went to work, to the railway station, to dinner, the theatre, to parties, to weddings, to hospital to have babies, to assignations, to divorce court and to funerals.

How can you put a price on all that history?

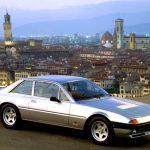

This article came courtesy of Hagerty UK – unfortunately both in the email and the image at the top of this page you show an FX4 which as the article says, is an entirely different vehicle. Sorry to nitpick – otherwise enjoy your articles

Fabulous story, well done!

Grazi for mkanig it nice and EZ.

I had an FX3 in 1972. It was in commercial use on New Years Eve and I bought it for £20. Petrol 2.2 (16HP) and I certainly got much more than 15MPG. Superb car, although it did raise some eyebrows when I turned up on “jobs” being a Customs Officer! Sure I had a heater in mine. As you say, lots of room. Many a happy mile.

Tried to book it in at local Austin dealer for a service, chap behind the counter disappeared and came back with an official service manual (I still have) and said “instead of booking a service, read the book and learn how to do it yourself. The knowledge will stand you in good stead and you’ll save money” Brilliant advice and he was right. 6 months later I stop at a zebra crossing, Ford Transit behind didn’t. Result, badly bent bumper and boot lid. Insurance co. wrote it off and a sold it later for £50. Good profit but I regret it now!!!