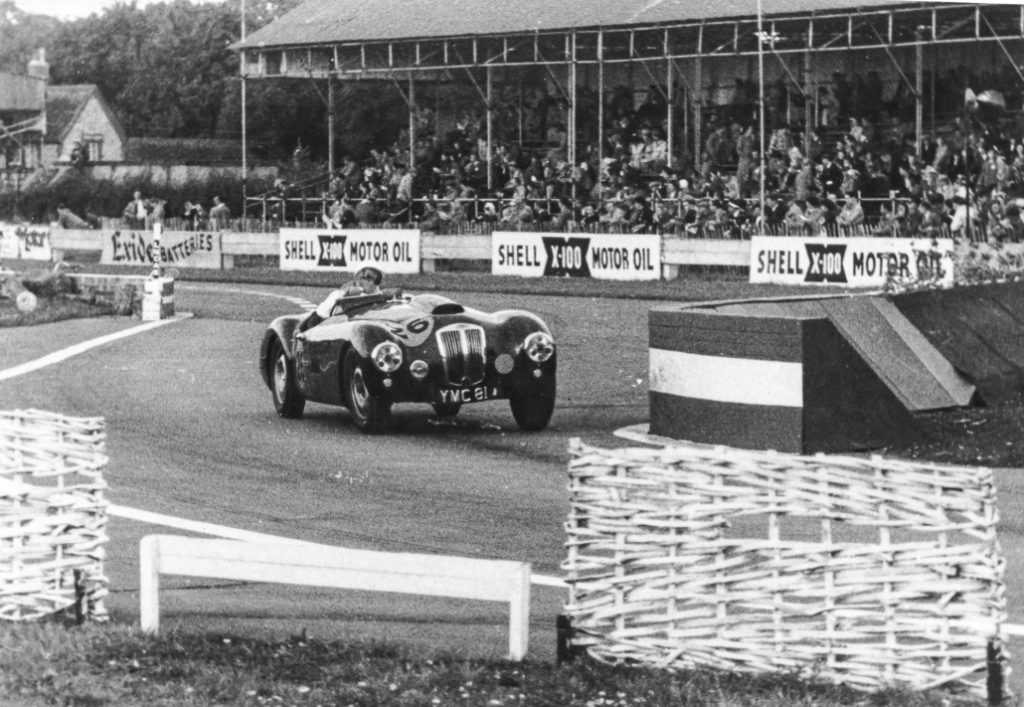

If you find yourself standing on the banks of Goodwood circuit this year, cast your mind back to 1952, the year this Mille Miglia sports racing car emerged from the Isleworth, Middlesex factory of Frazer Nash, to be delivered in July to a Mr A. S. Orr of Manchester.

The war might have been behind Britain and the rest of the world, but its lingering effects hung over us like the winter smog that plagued London. Rationing of confectionary, sugar and meat was still enforced – and the national staple of tea wouldn’t be freely available until October that year.

Still, there was always the rise of television to lift the spirits. Except, in February that year, the first TV detector vans (actually, they used Hillman Minx and Morris Oxford cars to begin with) hit the streets, promising to crack down on all those watching the box without paying a licence fee.

Cheer, then, was still in short supply. But the British Automobile Racing Club (BARC) reckoned it had just the thing. The body that was and remains responsible for running Goodwood motor sport events had overseen the successful development of Goodwood circuit, which drew crowds from far and wide, and now it wanted to take things a step (and many laps) further with the introduction of a long-distance race. Not any old endurance event, but one that would see sports cars race in both daylight and the darkness of night, starting at three o’ clock in the afternoon and running up until the stroke of midnight.

The Goodwood Nine Hours Race was born, and even if it was short lived, with the final event taking place in 1955, it was a welcome, high-octane distraction for its duration.

After the first owner sold the Mille Miglia back to AFN (Archie Frazer Nash, the company that built and sold Frazer Nash cars) it was snapped up by John Charles Broadhead – Jack to his friends – in June 1953. Broadhead made a good living through scrap machinery, owned a garage in Bollington, Macclesfield, and enjoyed spending the fruits of his labours on some rather special motor cars, including an ex-works Jaguar D-Type.

Doubtless he was attracted to the Mille Miglia because Frazer Nash had made a name for itself in motor racing. Stirling Moss, Roy Salvadori and Mike Hawthorn had all cut their teeth driving Frazer Nash cars, and the marque won its class at the Le Mans 24 hour race and even took the third step on the podium, in 1949, with the aptly named High Speed model. Never one to miss a sales opportunity, the name of subsequent High Speed cars was changed to Le Mans Replica. And in much the same way, the Mille Miglia had been called Fast Tourer up until the point the company put in a good showing at the 1950 1000-mile road race, and renamed it. (In ’51, Franco Cortese drove a Le Mans Replica to victory on the Targa Florio – the only British car to win the event.)

As was often the way then, Broadhead entered the Mille Miglia for some of the most high-profile motor sport events the British season had to offer, and handed it over to an experienced pair of hands, Peter Reece, and Gilbert Tyrer for driving duties including – 70 years ago this year – at the 1953 Goodwood Nine Hour race. The finisher’s commemorative plate, now nicely tarnished with age, is still with the car. The ’53 London Rally would follow, with the next year seeing the car compete at the RAC Rally, British Empire Trophy at Oulton Park, Prescott and the Silverstone Sports Car Race.

The Mille Miglia is rare, with just 11 built between 1949 and 1953. Two of those were the wide-bodied variant – this car being one of them, with more cockpit space. Compared to the Le Mans Replica, the Mille Miglia was a more sophisticated, streamlined design that featured full-width bodywork and a hood, while the intention of the wide-body versions was to make it suitable for touring. (The modern notion of building a road car that you can take to a race track or campaign at a hill climb course is nothing new…)

At £3307 for chassis number 166, the Mille Miglia was expensive, about £1500 more than a Jaguar XK120, so whichever gentleman was buying it with the intention of partaking in some spirited driving would have needed deep pockets.

It was a deeply attractive car, though, and in its favour, the Mille Miglia was found to have a beauty that was more than skin deep. It earned a reputation for being the kind of well-sorted car that drivers loved to hussle up to and beyond the limit, and the competition results backed this up.

The light, aluminium bodywork cloaks a tubular-frame chassis that was evolved subtly from the Le Mans Replica to allow for the lower bodywork, there are drum brakes, a four-speed gearbox (with synchromesh on all but first gear), transverse leaf-sprung front suspension and a torsion bar-sprung rear axle. Originally, all Mille Miglias featured a 2-litre six-cylinder engine known as the FNS1, which was derived from a BMW unit but designed specifically for Frazer Nash. Utilising triple-Solex carburettors, it boasted 125bhp and 123Ib ft of torque, in a car reported to weigh around 860kg.

Within the history file are all manner of fascinating invoices, race reports and literature of the period, and one that catches the eye is dated 8 February, 1954. The car was submitted to The Bristol Aeroplane Company for extensive work to remove, strip and clean the carbs, the piston crowns and valves, in amongst many other jobs and upgrades, and the bill came to a heady £184 – enough to buy a perfectly acceptable family car at the time.

However, the original engine is recorded as having been fitted to a Bristol in the early ‘60s, and in its place sits a period-correct Bristol 100D straight-six. Pendine, which is selling the Mille Miglia on behalf of its current owner, reports that the current engine number of 100D 716 correlates to an AC Ace Bristol, chassis BE 369, that competed in the 1958 RAC Rally. It points out that both car and engine took part in the event, four years apart.

Some noteworthy collectors have owned chassis 166 during its time, including the former car dealer and touring car racer, Frank Sytner, who was custodian from 1985 to 1987 and was responsible for having the original paint changed from Bristol Maroon to the racing green it now wears.

And now it’s my turn to get a feel for this rare machine. Getting in and out is surprisingly easy, and the dished seats envelope you more than expected. The layout is all a racing driver could hope for; legroom is perfect, the pedals, seat and steering wheel are straight-set. You’d happily wear the Smiths speedo on your wrist, so appealing is its authentic mechanical look, while everywhere you look this car wears its patina with pride – from the well-lived alloy and bakelite steering wheel to the fingered pull switches and turned alloy pressed into the leather-wrapped dashboard frame.

From cold and with just a touch of throttle and push of the starter button, the straight-six Bristol engine fires without protest and quickly settles to a steady idle, with a distinctive, heavy rasp that you’d expect of the configuration. And that roller-ball throttle pedal has a response that will be alien to anyone who has only driven modern cars.

Given the car’s pedigree, rarity and value, I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t if not nervous then at least conscious of my responsibilities while at the wheel of the Mille Miglia. Yet it’s reassuring to find that the clutch pedal has just the right weighting and plenty of feel, the gearbox has a delightfully short but positive throw (like a Honda S2000) and the engine has impeccable manners whatever the revs. It’s on your side.

Trundling around Bicester Heritage at low speeds show that it is entirely manageable and easy to get on with, while out on the road beyond the confines of the site it really comes alive beyond 3000rpm, with the red line of 5500rpm comparatively high for an engine of its time.

It is rare that you jump into a car and immediately feel at home, sensing an innate rightness to everything it does, but this seems to be one of those rare moments. The pliancy of the suspension, response of the steering and feeling of the front and rear axles working in harmony encourages you to press on, but… well, that will have to wait for another day, perhaps, one where speed limits and other road users aren’t present. If only the track at Bicester Heritage had been available for a hot lap or two.

The cost of the Mille Miglia and rise of more competitive racing machines from Cooper and Lotus probably put paid to the model’s life, while the owner of AFN believed the future lay in importing and selling Porsches, rather than designing, engineering and marketing its own cars.

It goes without saying that owning a storied car like this should help those with a burning desire to attend retrospective events such as the Mille Miglia or wanting to scratch the racing itch and get on the grid at Goodwood or Rolex Reunion. It rubbed wheelarches and spinners with Aston Martin DB3s, Jaguar C-Types and Austin-Healey 100s, and could – should – do so again.

And that prompts the inevitable question: how much? Pendine, which is selling the car on behalf of its owner, gives a figure of £695,000. When you weigh that against the aforementioned ‘gentleman racers’, the C-Type and DB3S, which broadly speaking can be valued between £4 to £7 million, (and we’re first to acknowledge that the history of these racers plays a significant part in their allure) the lesser-known Mille Miglia has an appeal all of its own.

Rest assured, just as the crowds were appreciative of this racer doing its thing on track, back in the day, so they will be 70 years later.

With thanks to Pendine. To enquire about the Frazer Nash Mille Miglia click this link visit the website or call on 01869357126.

Read more

There’s only one Jaguar XJ13 – and they let me drive it

Driving the Greats: A Citroën SM is one of life’s great pleasures

Retro Rematch: Aston Martin V8 Vantage vs Audi R8 4.2

I think there is still a Broadheads Garage in Bollington. I used to get my car MOT’d there.